II.2.2.2. Willingness to pay as a result of one's

preference

The notion of willingness to pay broadly roots from consumer's

demand function (Varian, 1992). Opting for paying can be beheld as the

translation of one's utility got from a related good or service (Varian, 1992;

Jha and Bhalla, 2018). But being unwilling to pay for a commodity should not

intuitively pass as an evidence of total absence of willingness to pay (Matraia

et al., 2006). It all depends on the opportunity cost that forgoing a slight

share of one's income implies (Jha and Bhalla, 2018).

Jha and Bhalla (2018) hereon highlight willingness to engage

and the ability to engage referring to community aptitude to contribute for

contending poverty. Associated engagement thus relies on sensitization of new

community members to lift the impact of their action toward the target.

Let's then consider a collection of consumers as referred to

Varian (1992). Each one of them faces a demand function for some k commodities

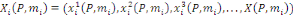

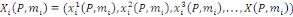

so that a consumer's demand function becomes a vector   for for  . .

Note: goods are indicated by superscripts while consumers are

indicated by subscripts.

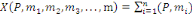

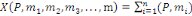

Aggregating these individual demands helps to obtain a unique

aggregate demand function

defined by   .Then, the aggregate demand for goods .Then, the aggregate demand for goods   can be denoted by can be denoted by   ; with m, the vector of incomes ; with m, the vector of incomes   ). As a centralizing function, the aggregate function is made of

individual demand function characteristics. A reference is for instance

directly taken from continuity of the individual demand function. Assume a

consumer is able to acquire only one chair for given price ). As a centralizing function, the aggregate function is made of

individual demand function characteristics. A reference is for instance

directly taken from continuity of the individual demand function. Assume a

consumer is able to acquire only one chair for given price  . At any other price . At any other price   such as such as   exceeds the initial price exceeds the initial price  , consumer , consumer   demands zero of the good. On the other hand, each other price demands zero of the good. On the other hand, each other price   inferior or equal to inferior or equal to   implies implies  's consumption of one unit of the good. From this demonstration,

consumer's preference can be ranked by the means of this set of prices: 's consumption of one unit of the good. From this demonstration,

consumer's preference can be ranked by the means of this set of prices:   such as [ such as [  ] represents consumer willingness to pay side and, in contrast, at ] represents consumer willingness to pay side and, in contrast, at   the consumer can't face the proposed price higher than the initial

price and, as result, none is disposed to pay. the consumer can't face the proposed price higher than the initial

price and, as result, none is disposed to pay.

Indeed, WTP of public goods such as environment conservation

or getting comfortable infrastructure is relatively complex. In light of this,

better is to understand how WTP varies regarding to the transparency of

institutions.

II.2.2.3. Institutional trust and Willingness to pay

When people are needed to pool for a common good or service,

what first happens for each one of them is somehow hedonic. Gain motives first

their decisions towards disbursing for a given realization. Multiple are those

kinds of communal schemes that have failed and so are state-folks cooperation

in specific developmental ventures when one of the part is not seriously

engaged in the ideology and practical fulfillment.

From that mood, willingness to pay is affected by the

institutional trust (Macias and Williams, 2014). Jin (2013) defines

institutional trust as «the extent to which citizens have confidence in

public institutions to operate in the best interest of society and its

constituents». The credibility and legitimacy of developmental policies

reflect a successful fulfillment of people's trust in institutions (Islam et

al., 2019; Uddin, 2019). "The lower the level of trust in the state actors

tasked with the provision of the public good, the lower the likely valuation

individuals will attach to the good in question which ultimately affects their

WTP toward its provision" (Marbuah, 2016). Other needful elements in bettering

community-governance interaction are transparency and accountability of the

ruling regime. Both elements must be conveyed through access to information

(Ampa, 2018). The issue of mistrust in institutions has been found to be one of

the main reasons for citizens' protest responses and lower WTP in many

environmental valuation studies (Jones et al., 2008; Polyzouet al., 2011).

|