Chapter 2: Linking strategy with information

technology through a value chain approach

In this chapter, the literature review is based on the

relationship between technology and strategy, and the competitiveness impact of

IT on the enterprise. Included is a discussion of the technical, strategic

planning model (value chain approach) to evaluate Axapta software. The

definition of and debate on the concept of the value chain are also

highlighted, followed by a discussion of the impact of IT in the value chain,

the role of value chain integration and the relationship between e-business and

ERP for value chain extension benefits.

Chapter 3: An overview of ERP systems

In this chapter, the discussion is based on the definition

and analyses of the ERP system concept as a value chain system, its background,

as well as its benefits, characteristics, advantages and disadvantages. The

discussion of the general model of an ERP system will be highlighted and its

roles, global architecture and configuration under an MNE strategy will also be

discussed. In addition to the assessment of the strategic supply chain factors

for the evaluation of ERP software considered before adoption, matters related

to the methodology and the success and failure of an ERP system implementation

project within an organisation are also discussed.

Chapter 4: A case study of ERP systems - Axapta

Microsoft software solution

In this chapter, a case study regarding Axapta Microsoft

software solution is discussed according to the generics, modules and

architecture of the software.

17

Chapter 5: Research methodology

This chapter focuses on the research hypotheses formulated

and it provides a detailed discussion of the research type, methodology and

design of this study, including data-gathering methods and procedures used. It

also explains how the methodology of this research was conducted to gather the

data.

Chapter 6: Research findings and interpretation of data

analysis

This chapter is dedicated to presenting the research results

of the collected qualitative and quantitative data related to the ERP system

Axapta Microsoft and SAP software. It includes the results in different tables,

graphs and explanations of the primary data collected in order to complement

the relevant literature, which reinforces the findings of this study.

Chapter 7: Conclusions and recommendations

A conclusion is reached addressing the research objectives

and the finding of this study, followed by a display of the methodical approach

formulated by the researcher to assess ERP software before acquisition and

implementation.

18

CHAPTER 2: LINKING STRATEGY WITH INFORMATION

TECHNOLOGY

THROUGH A VALUE CHAIN APPROACH

2.1 Introduction

It is the objective of this chapter to analyse the strategic

importance of information system (IS), linking it with strategy. It is for this

reason that the value chain, as a strategic planning tool, will also be

evaluated. This enables the researcher to measure the effectiveness of an ERP

system, i.e. Axapta Microsoft software, as a strategic IT tool for MNEs.

2.2 The interdependence of technology and

strategy

Burgelman, Maidique and Wheelwright (2001:6) explain the

development of connecting technology and strategy as follows: "During the

1980s, strategic management scholars began to recognise technology as an

important element of business definition and competitive strategy." Abell in

Burgelman et al., (2001:6) identifies technology as one of three principal

dimensions of business definition, noting that "technology adds a dynamic

character to the task of business definition, as technology more or less

rapidly displaces another over time". Furthermore, Porter (in Burgelman et al.,

2001:6) observes that technology is among the most prominent factors that

determine the rules of competition. Friar and Horwitch (in Burgelman et al.,

2001:6) explain the growing prominence of technology as the result of

historical forces that encompass the disenchantment with strategic planning,

the success of high-technology organisations in emerging industries and the

surge of Japanese competition. This is in addition to the recognition of the

competitive significance of manufacturing.

The four elements that constitute the substantive dimensions

of technology in strategy, as explained by Burgelman et al., (2001:36), are as

follows: (1) The deployment of technology, which can be positioned in terms of

differentiation (perceived value or quality), delivered cost and to gain

technology-based competitive advantage; (2) the use of technology, which can be

seen more broadly in the various activities comprised by the organisation's

value chain; (3) the organisation's resource commitment to various areas of

technology; and (4) the organisation's use of organisation design and

management techniques to manage the technology function. Johnson and Scholes

(2002:10-16) define strategy as the direction and scope of an organisation over

the long term, which achieves advantage for the organisation through its

configuration of resources within a changing

19

environment and to fulfil stakeholder expectations. Strategic

management therefore includes an understanding of the strategic position of an

organisation and strategic choices for the future in an effort to turn strategy

into actions.

Turban, McLean and Wetherbe (2004a: 6) state that IT supports

strategic management through:

· Innovative applications that provide direct strategic

advantage to organisations;

· The changes in processes: where IT supports changes in

business processes that translate to strategic advantage;

· The competitive weapon: where IS itself is recognised as

a competitive weapon;

· The links with business partners: where IT links a

company with its business partners effectively and efficiently;

· Cost reductions: where IT enables companies to reduce

costs;

· The relationships with suppliers and customers: where IT

can be used to lock in suppliers and customers, or to build in switching

costs;

· New products: where IS enables an organisation to

leverage its investment in IT to create new products that are in demand in the

marketplace; and

· Competitive intelligence: where IT provides competitive

(business) intelligence by collecting and analysing information about products,

markets, competitors and environmental changes.

Therefore it can be concluded that IT helps businesses to

pursue the following four basic competitive strategies: (1) Developing new

market niches; (2) Locking in customers and suppliers by raising the cost of

switching; (3) Providing unique products and services; and (4) Helping

organisations in the provision of products and services at a lower cost by

reducing production and distribution costs.

2.3 The role IT plays within strategy

Dewett and Jones (2001:313-14) mention that an IS includes

many different varieties of software platforms and databases. These encompass

organisation-wide systems designed to manage all major functions of the

organisation provided by companies such as SAP, PeopleSoft, JD Edwards, to name

only a few. In addition, more general-purpose database products are found,

targeted with

20

specific uses such as the products offered by Oracle and

Microsoft. Thus, the result is IT encompassing a broad array of communication

media and devices, which link IS and people. Typical ISs include voicemail,

e-mail, voice conferencing, video conferencing, the Internet, GroupWare and

corporate intranets, car phones, fax machines and personal digital assistants.

Therefore as IS and IT are often inextricably linked and, since it has become

conventional to do so, for the rest of this study both IT and IS will be

referred to jointly as IT. A study done by Ward and Griffiths (in Corboy,

2002:7) stipulates that the reason IT could be used for gaining competitive

advantage is its status of:

· Linking the organisation to the customers and suppliers,

through electronic data interchange (EDI), websites, wide area networks (WANs)

and extranets;

· Creating effective integration of the use of information

in a value-adding process, e.g. data mining, data warehousing and ERP

systems;

· Enabling the organisation to develop, produce, market and

distribute new products or services, e.g. computer aided design (CAD) and CRM;

and

· Giving senior management information to help them to

develop and implement strategy through knowledge management, for instance.

IT plays a vital role in improving co-ordination,

collaboration and information sharing, both inside and across organisational

boundaries. It allows more effective management of task interdependence and

facilitates the creation of integrated management information, while

simultaneously offering new possibilities for MNEs.

The generic IT capabilities and their impact on organisations,

highlighted by Siriginidi (2000:376), are:

· Transactional capabilities, which transform unstructured

processes into structured transactions;

· Geographical capabilities, which transfer information

rapidly and with ease across large distances, thus making the processes

independent of geography;

· Automation, which replaces or reduces human labour in

processes;

21

· Analytical capabilities, which introduce complex

analytical methods to enlarge the scope of analysis;

· Informational capabilities, which bring vast amounts of

detailed information into the process;

· Sequential capabilities, which enable changes in the

sequence of tasks in a process, often allowing multiple tasks to be performed

concurrently;

· Knowledge management, which allows collection,

dissemination of knowledge and expertise to improve the process;

· Tracking, which allows detailed tracing of task status,

inputs and outputs; and

· Disintermediation, which connects two parties, internal

or external, within a process that would otherwise communicate through

intermediaries.

According to Dewett and Jones (2001:314), the findings of

Huber's study suggest that IT is a variable that can be used to enhance the

quality and timeliness of organisational intelligence and decision-making, thus

promoting organisational performance. However, Huber's research extends the

role and use of IT into the organisation in the strategic manner of efficiency

and innovation. This captures many of the specific benefits and the examination

of organisational functioning by describing the impact of IT on a broader array

of organisational characteristics from the use of IT to its theory, which

treats several organisational characteristics. The research further introduces

theory, which treats several organisations as dependent variables, with IT

positioned as the independent variable. Indeed, an ERP system is the IS tool

and expression of the inseparability of business and IT. It is not possible to

think of ERP implementation without a sophisticated IT infrastructure (Gupta,

in McAdam & Galloway, 2005:281).

2.4 The importance of a strategic IT plan within an

organisation

According to Bakehouse and Doyle (2002:1), the planning of an

IT strategy is a decision-making process. Such a crucial process should be

undertaken carefully, systematically and an understanding of the business

context.

A study conducted by Peppard in Corboy (2002:6) revealed that

the meanings of having a strategic

IT plan within an organisation are seen

as establishing entry barriers, affecting the cost of switching

operation,

differentiating products/services, limiting access to distribution channels,

ensuring

22

competitive pricing, decreasing supply cost, increasing cost

efficiency, using information as a product and building closer relationships

with suppliers and customers. In addition, the study conducted by Earl (in

Corboy, 2002:3) provides a useful list of reasons as to why an organisation

should have a strategic IT plan:

· High costs are involved and it is critical to the success

of many organisations.

· IT is now used as part of the commercial strategy in the

battle for competitive advantage.

· IT is required by the economic context (from a

macro-economic point of view).

· IT affects all levels of management and the detailed

technical issues in it are important.

· IT has meant a revolution in the way information is

created and presented to management.

· IT involves many stakeholders, not just management.

· IT requires effective management, as this can make a real

difference to successfully using it.

2.5 The value chain and IT, linked to strategic

management

The value chain can be helpful in understanding how value is

created or lost. It describes the activities within and around an organisation,

which together create a product or service. It is the cost of these

value-adding activities that determines whether or not products or services are

developed, which in turn underpins competitiveness (Johnson & Scholes,

2002:117).

According to Corboy (2002:6), the value chain model can be

used to assess the impact of IT on the elements of an organisation's individual

value chain and how it is integrated with other value-adding activities. Thus,

a value chain can be used to evaluate a company's process and competencies and

investigate whether IT supports add value, while simultaneously enabling

managers to assess the information intensity and role of IT. Turban, King, Lee

and Viehland (2004b: 11) state that the value chain is the series of

value-adding activities that an organisation performs to achieve its goals at

various stages of the production process categorises the generic value-adding

activities of an organisation and also the primary activities supported by the

secondary activities. Furthermore, it analyses the forces that influence a

company's competitive position, which assist management in crafting a strategy

aimed at establishing a sustained competitive advantage.

In an effort to establish such a position, Turban et al.,

(2004a: 16) suggest that a company needs to

23

develop a strategy of performing activities differently than a

competitor through:

· Cost leadership strategies: Produce products and/or

services at the lowest cost in the industry;

· Differentiation strategies: Offer different products,

services, or product features;

· Niche strategies: Select a narrow-scope segment (niche

market) and be the best in quality, speed, or cost in that market;

· Growth strategies: Increase market shares, acquire more

customers, or sell more products;

· Alliance strategies: Work with business partners in

partnerships, alliances, joint ventures, or virtual companies;

· Customer-orientation strategy: Concentrate on making

customers happy;

· Innovation strategies: Introduce new products and

services, put new features in existing products and services, or develop new

ways to produce them;

· Operational effectiveness strategies: Improve the manner

in which internal business processes are executed so that an organisation

performs similar activities better than rivals;

· Time strategies: Treat time as a resource, then manage it

and use it to the organisation's advantage;

· Lock-in customer or supplier strategies: Encourage

customers or suppliers to stay with you rather than going to competitors;

· The entry-barriers strategy: Create barriers to entry;

and

· Increase switching cost strategies: Discourage customers

or suppliers from going to competitors for economic reasons.

All this will motivate organisations to perform activities

differently than a competitor while linking those activities to the value

chain. The value chain is a series or «chain» of basic activities

that adds marginal increments of value to an organisation's products or

services. IT plays a strategic role in those activities that add the most value

to the organisation. Does Axapta software support strategic management within

the MNE? Has Microsoft positioned Axapta competitively, which will assist MNE

management to craft a strategy aimed at establishing a sustained competitive

strategy? These issues will be discussed further in chapter 6 in relation to

the hypotheses formulated in chapter 1.

24

2.6 Definition of the value chain concept

The initial purpose of the value chain was to analyse the

internal operations of an organisation, in order to increase its efficiency,

effectiveness and competitiveness. However, nowadays it extends to the company

analysis, by systematically evaluating a company's key processes and core

competencies in order to eliminate any activities that do not add value (Turban

et al., 2004a: 20).

In a study done by Walters and Lancaster (1999:646-47) different

scholars and researchers described the value chain analysis concept as

follows:

1. O' Sullivand and Geringer remind us of the purpose of

value chain analysis by explaining that the organisation has limited access to

resources, and the purpose of the value chain is to ensure that the resources

of the organisation work in a co-ordinated way to take full advantage of

market-based opportunities. In addition the analysis should identify the

optimal configuration of both the macro- and micro-business systems that will

maximise value expectations. Thus, the conceptual concerns of the supply chain

and the value chain begin to converge.

2. Brow pursues a conventional approach to the value chain by

introducing two additional perspectives to the debate by putting the emphasis

on the links or relationships between activities in the value chain and the

organisation's competitive scope as a source of competitive advantage. Brow

mentions that links and relationships between buyers, suppliers and

intermediaries can lower cost or enhance differentiation. The competitive scope

may concern the range of products or customer types (segment scope), the

regional coverage (geographic scope), or its activities across a range of

related industries (its industry scope).

3. Porter proposed the value chain as a means by which business

actions that transforms inputs could be identified (i.e. value chain stages).

Furthermore, from its study the proposition formulates suggested that those

stages in the value chain can be explored for interrelationships and common

characteristics. This could lead to the opportunities for cost reduction and

differentiation.

Porter provides a detailed view of the value chain and its

efficacy and states that its purpose at either macro or micro level is to:

· Identify relationships and interdependence between

stages for both systems within the organisation;

25

· Identify meaningful differentiation characteristics,

which are unique, or exclusive, to the organisation;

· Identify costs and cost profiles within the organisation

together with cost advantages that could exist, and identify the business

actions (stages) which transform inputs;

· Choose its competitive positioning market segments,

customer applications/end-uses and the technologies; and

· Identify alternative value chain delivery structures

(i.e. interrelationships internally and between business units) within the

industry delivery structure.

Therefore, according to Porter (1990:40), both macro- and

micro-business systems should consider the value creation process, more

recently in the interests of shareholders, suppliers and employees (together

with those of the community) included in a broader view of stakeholder

interests and value. In addition, Porter (1990:40) explains the concept of the

value chain in competition as follows:

"Competitive advantage grows out of the way organisations

organise and perform discrete activities. The operations of any organisation

can be divided into a series of activities such as salespeople making sales

calls, service technicians performing repairs, scientists in the laboratory

designing products or processes and treasurers raising capital. Organisations

create value for their buyers through performing these activities. The ultimate

value an organisation creates is measured by the amount buyers are willing to

pay for its product or service. An organisation is profitable if this value

exceeds the collective cost of performing all of the required activities.

Organisations gain competitive advantage from conceiving of new ways to conduct

activities, employing new procedures, new technologies, or different inputs. An

organisation's value chain is an interdependent system or network of

activities, connected by linkages. Linkages occur when the way in which one

activity is performed affects the cost or effectiveness of other activities.

Linkages also require activities to be co-ordinated. Gaining competitive

advantage requires that an organisation's value chain is managing as a system

rather than a collection of separate parts. Competitive advantage is a function

of either comparable buyer value more efficiently than competitors (low cost),

or performing activities at comparable cost but in unique ways that create more

buyer value than competitors and, hence, command a premium price."

26

Thompson and Strickland (1987:115) stress that the primary

analytical tool of strategic cost analysis is a value chain, which must

identify the separate activities, functions and business processes performed in

designing, producing, marketing, delivering and supporting a product or

service. The chain starts with raw materials supply and continues on through

parts and components production, manufacturing and assembly, wholesale

distribution and retailing to the ultimate end-user of the product or service.

Johnson and Scholes (2002:160) describe in a simplistic way the value chain as

the activities within and around an organisation, which together create a

product or service.

In a study done by Walters and Lancaster (2000:160), Brown

offered a succinct definition of the value chain as follows: " The value chain

is a tool to disaggregate a business into strategically relevant activities.

This enables identification of the source of competitive advantage by

performing these activities more cheaply or better than its competitors. Its

value chain is part of a larger stream of activities carried out by another

member of the channel-suppliers, distributors and customers." The three

important perspectives that emerged from the study of Walters and Lancaster

relating to the value chain are:

· Firstly that it emphasises the relationship between

activities in the value chain;

· Secondly, the need for the first to result in competitive

advantage; and

· Thirdly, to identify the role of information to

evaluate the nature of opportunities offered, identify optional methods for

competing and co-ordinate the value chain's activities towards successful

implementation of the value strategy.

2.7 Different graphic representations of the value

chain

2.7.1 Porter's value chain

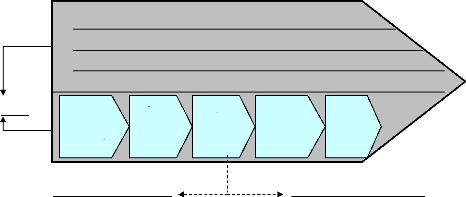

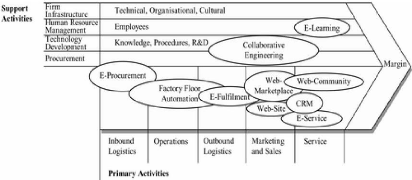

The Porter's value chain model categorises nine generic

value-adding activities of an organisation (Johnson & Scholes, 2002:160),

as shown in figure 2.1 below. The model constitutes two broad types of

categories: primary and support activities.

The primary activities are those activities involved in the

physical creation of the product or service, its delivery and marketing to the

buyer and its support after sale. The support activities merely provide the

infrastructure that allows the primary activities to take place on an ongoing

basis. The five main areas of primary activities are:

27

· Inbound logistics, which are the activities

concerned with receiving, storing and distributing the inputs to the product or

service. They include materials handling, stock control and transport, etc.

· Operations, which transform these various inputs into the

final product or service: machining, packaging, assembly, testing, etc.

· Outbound logistics, which collect, store and

distribute the product to customers. For tangible products this would be

warehousing, materials handling, transport, etc. In case of services, they may

be more concerned with arrangements for bringing customers to the service if it

is a fixed location.

· Marketing and sales, which provide the means of making

consumer/users aware of the product or service and enabling them to purchase

it. This typically includes sales administration. In public services, it will

be communication networks, which help users to access a particular service.

· Service, which includes all those activities that enhance

or maintain the value of a product or service, such as installation, repair,

training and spares.

Figure 2.1: Porter's value chain model

Secondary activities

Value

Primary activities Primary activities

Upstream value activities Downstream value activities

Inbound

logistics

(raw materials,

handling

and

warehousing)

(machining, assembling, testing)

Operations

Firm infrastructure

(general management, accounting, finance, strategic

planning)

Procurement

(purchasing of raw materials, machines,

supplies)

Human resource management

(recruiting, training,

development)

Technology development

(R&D, product and process improvement)

(warehousing

and distribution

of

finished

product)

Outbound

logistics

(Advertising, promotion, pricing, channel

relations)

Marketing and

sales

(Installation, repairs, parts, etc.)

Services

Source: Adapted from Turban et al., (2004a: 11).

28

The element of primary activities can be broken down to form a

particular activity. Those primary activities, which occur before outbound

logistics, are commonly referred to as upstream value activities, while those

that occur after outbound logistics are called downstream value activities.

The upstream logistics are more important for buyers, while

downstream logistics are more important for the marketers of the organisation's

products. Each of these groups of primary activities is linked to support

activities. Support activities help to improve the effectiveness or efficiency

of primary activities and are divided into four areas:

· Procurement, which refers to the processes for acquiring

the various resource inputs to the primary activities. As such, it occurs in

many parts of the organisation.

· Technology development, where all value activities

have a «technology», even if it is just know-how. The key

technologies may be concerned directly with the product (e.g. R&D, product

design) or with processes (e.g. process development) or with a particular

resource (e.g. raw materials improvement). This area is fundamental to the

innovative capacity of the organisation.

· Human resource management, which is a particularly

important area, which transcends all primary activities. It is concerned with

those activities involved in recruiting, managing, training, developing and

rewarding people within the organisation.

· Infrastructure, which the system that plans the finance,

quality control and information management.

In most industries it is rare for a single organisation to

undertake all of the value activities in-house from the design to the delivery

of the final product or service to the final consumer (Johnson & Scholes,

2002:160). However, although the names that attribute processes to each

activity differ, the organisations perform activities more or less in the same

way. In the study of Walters and Lancaster (2000:162-3), Sutton reminds us of

«the totality surrounding one organisation as the value chain». Each

step can only be justified if it creates more value to the end-user than it

consumes as cost. An individual organisation's competitive position depends on

the effectiveness of the chain as an entity, not just its own position as a

link in the value chain.

2.7.2 The customer-centric value chain

Highly competitive markets and abundant information have placed

the customer at the centre of the

29

business universe. In this new environment, successful

business are those that employ customer-centric thinking to identify customer

priorities and construct business designs to match them (Slywotzky &

Morrison, 1997:17). Slywotzky and Morrison (1997:28-29) comment that in

«the old economic order, the focus was on the immediate customer. Today,

business no longer has the luxury of thinking about just the immediate

customer. To find and keep customers, the perspective has to be radically

expanded. In a value migration world, the vision must include two, three, or

even four customers along the value chain. For example, a component supplier

must understand the economic motivations of the manufacturer who buys the

components, the distributors who take the manufacturer's products to sell, and

the end-user».

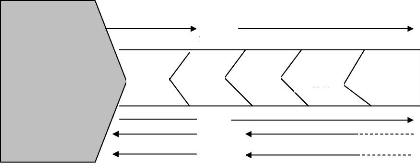

According to Slywotzky and Morrison (1997:20), the

traditional value chain begins with the company's core competencies, its

assets. It then moves to inputs and other raw materials, to an offering, to the

channels, and then finally to the customer, as shown in figure 2.2 below.

Figure 2.2: The traditional value chain

Assets/Core

Competencies

Inputs, Raw

Material

Product/Service

Offering

Channels The Customer

Source: Adapted from Slywotzky and Morrison (1997:20).

Therefore Slywotzky and Morrison use a "customer-centric"

approach to propose a modern value chain, as shown in figure 2.3, in which the

customer is the first link to all that follows. The approach therefore changes

the traditional value chain in that it takes on a customer-driven perspective.

Slywotzky and Morrison (1997:20-7) state that an organisation's value chain

must merge with those of other value chain members. Figure 2.3 below takes an

industry perspective of this value chain where IT provides a co-ordinating

function.

As is evident in the customer-centric value chain, the task of

management is to identify the

30

customer needs and priorities of the channels that can

satisfy those needs and priorities, the services and products best suited to

flow through those channels, the inputs and raw materials required in creating

the products and services and the assets and core competencies essential to the

inputs and raw materials.

Figure 2.3: The customer-centric value chain

Value criteria Security

Performance

Aesthetics

Convenience

Economy Reliability

Channels

Information

Value added

Costs added

Customer

Value Value offer Inputs, raw

Attributes Channels materials

Assets and core

Competencies

Source: Adapted from Slywotzky and Morrison in Walters and

Lancaster (1999:648).

2.7.3 Scott's value chain

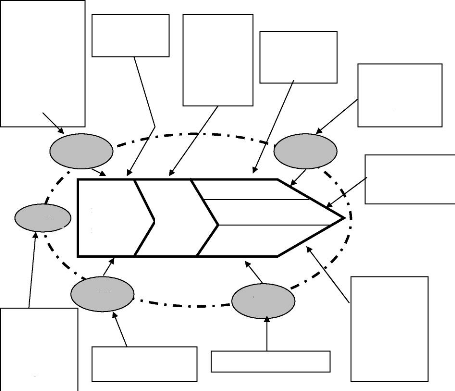

Scott (1998:87) notes that all organisations, whether

industrial or services, have a value chain. Each part needs a strategy to

ensure that it drives value creation for the whole organisation. For a piece of

the value chain to have a strategy means that it must be clear on what

capabilities the organisation requires to deliver effective market impact.

Walters and Lancaster (1999:648) explain Scott's value chain

by taking a strategic management view and using the value chain concept to

identify the tasks necessary to deliver a product or service to the market.

Therefore, Scott's approach to the value chain combines segmentation and value

chain analysis, followed by suggesting a number of questions such as: In which

areas of the value chain does the organisation have to be outstanding to

succeed in each customer segment? What skills or competencies are necessary to

deliver an outstanding result in those areas of the value chain? Are they the

same for each segment or do they differ radically? According to Scott

(1998:17), in order to segment an organisation or a product based on

competencies it is necessary to

31

understand the value chain of the company. The core elements

of Scott's value chain shown in figure 2.4 comprises seven areas: (1)

operational strategy; (2) marketing sales and service strategy; (3) innovation

strategy; (4) financial strategy; (5) human resource strategy; (6) information

technology strategy; and (7) lobbying position with government. In the Scott

value chain, coordination across the value chain is essential, which did not

occur in the traditional value chain.

Figure 2.4: An alternative view of the value chain

drivers

· Application rates

· Staff turnover

· Labour productivity

· Hierarchy/layers

· Accountability

· Remuneration ratios

· Ownership

· Bonusing

· Speed of promotion

· Training/revenue

· Internet comms

· Space/employee

· Cost

· Unionisation

· Leverage

· Cost of debt

· Debt maturity

· Investor relations

· Dividend policy

· Cost structure

· Cash flow

· Internal controls

· Acquisitions

Finance

Human resource

management

Innovation

Purchasing and

Supplier Process

· Relationship

quality

· Material inventory costs

· Unit input

· R&D training/revenue

· Patents/100 Employees

· New product launches

· Position on innovation curve

Core Production Process

· Unit costs - Utilisation

- Scale

- WIP

· Quality - Scrap rate

- Rework

· Timeliness - Cycle time -Throughput

time

· Flexibility -

Changeover time

· Exposure to regulatory change

· Lobbying capability

Distribution

Marketing

Sales and service

Government

relations

· Speed to market

· Finished goods

inventory

· Unit distribution Cost

Information

technology

· Customer targeting

· Customer loyalty

-

Churn

· Customer acquisition

· Customer yield

· SOV

· Unprompted

recall

· Price premium

· IT spend/revenue

· Communications

networks

· Knowledge sharing

· Value chain integration

· Channel complexity

· Channel control

· Trade relationships

· Market responsiveness

· Customer churn

Source: Adapted from Scott (1998:87-222).

Scott's study of the value chain emphasised primarily the

relationship between the company's value

32

chain and its strategic business units (SBUs). Furthermore,

according to Scott (1998:88), certain parts of the value chain are likely to be

common to all its SBUs. These include human resources, IT and large parts of

its financial and selling functions. Therefore Scott concludes that the

information requirements of individual SBUs might differ and require specific

services. In a market/customerfocused business, the core elements of the

business should be capable of developing specific service inputs to ensure

competitive advantage.

2.7.4 Walters and Lancaster's value chain

The value opportunities are distinguished by understanding

customers' priorities and producing, communicating and delivering the

identified value. This suggests that the value chain must be an analytical and

a facilitating concept (Walters & Lancaster, 2000:161-165). However,

strategy must be considered as the value-creating system itself in which

members work together to create value. Normann and Ramirez (1998:29) note that

offering goods and/or services is the result of a complex set of value-creating

activities involving different actors working together at different times and

locations to produce them for and with a customer. Walters and Lancaster

(2000:162) point out that the key strategic task is the reconfiguration of the

value chain roles and relationships in order to «mobilise the creation of

value in new forms and by new players». They further state that the

underlying goal is to "create an ever improving fit between competencies and

customer". To understand how this may be achieved, two models are required. The

first is a model of the value chain itself and the second is one describing the

value chain structures and processes.

According to Walters and Lancaster (2000:162-3), the value

chain depicted in figure 2.5 combines the two models. Topics and subcomponents

describe the notion of customer value, comprising customer value criteria less

their acquisition costs. In order for the value chain to be successful it is

essential that the individual objectives of all stakeholders as well as those

of customers be met. It is important to note that value production and

co-ordination are created by identifying and understanding customer benefits

and costs, and the combinations of organisational knowledge and learning,

together with organisational structures that facilitate response and delivery.

Essentially it requires the management of information and relationships. An

important influence is the impact of the value and cost drivers, which in turn

are the important strategic and operational relationship criteria influencing

value delivery and cost structures. A depiction of components of the value

chain is displayed in figure 2.5 below. "Corporate value" is a value chain

perspective of profitability and

33

cash flow objectives, "knowledge" refers to market-based

intelligence developed for strategic and operational use within the value chain

and "information management" components include market identification, time,

accuracy, relevance and control aspects. Walters and Lancaster (2000:162) claim

that relationship management comprises the obvious co-ordination activities

together with coproduction (upstream and downstream within the value chain),

co-destiny (the promotion of interdependence), cost management (to achieve

optimal value chain costs for the value added throughout) and cost transparency

(the notion that effective co-operation and co-ordination are only achievable

if visibility exists).

Figure 2.5: The value chain components model

Key success factors

Value proposition

'Corporate value'

· Profitability

· Productivity

· Cash flow

· 'Knowledge'

Information management

· Identification

· Time

· Accuracy

· Relevance

· Control

Value

strategy and

positioning

Organizational structure and

management

· Knowledge

· Learning

· Partnerships

Value production

and coordination

Operation structure and management

'Production'

· Time to market

· Service

· Quality

· Risk

· Cost management

· Reputation

Relationship management

· Coordination

· Coproduction

· Codestiny

· Cost management

· Cost transparency

|

· Sourcing and procurement

· Production processes

· Flexibility

'Logistics'

· Order management

· Delivery

· Reliability

· Availability

|

|

Value/

cost

drivers

Customer value criteria

· Security

· Performance

· Aesthetics

· Convenience

· Economy

· Reputation

|

|

|

Customer value added = Results produced for

the customer and the process quality

less

Price to the customer and the cost of acquiring the product

service

Customer acquisition costs

· Specification

· Search

· Transactions

· Installation

· Operations

· Maintenance

· Disposal

Source: Adapted from Walters and Lancaster (2000:163).

In his influential book Competitive

advantage, Porter (1985) depicts the relationships between actors

in a productive system in terms that are uni-directional and sequential in

nature. In Porter's value chain notion, economic actor A sells (or passes on)

the output of his work to actor B, who 'adds' value to it, and sells or passes

it on to actor C, who adds value to it, and sells or passes it on to actor D,

and so on until it is sold to the end-consumer. However, with microprocessor

technologies, economic actors are increasingly engaged in sequential and

simultaneous activity relations with other economic actors. Thus, Normann and

Ramirez (1998:viii) assert that provider-customer

34

relationships should be conceived not as one-way transactions

but reciprocal constellations in which the parties «help each other and

help each other to help each other». In addition, Walters and Lancaster

(2000:162) argue that the organisational structure management is concerned with

ensuring that maximum use is made of knowledge generated in the value chain and

partnerships, which lead to effective learning.

Therefore Walters and Lancaster (2000:163) conclude that the

activities and topics influence the production and co-ordination of value

delivery through the impact of the value/cost drivers. Not surprisingly, the

value/cost drivers influence organisational and operations structure and their

management. As figure 2.5 infers, both production and logistics are important

components of the operations structure, which is the other input into value

production and co-ordination. The impact of globalisation (for procurement and

marketing purposes) has made the value chain a more useful approach to

identifying and evaluating business opportunities. The view of value chain

structure and process mentioned by Walters and Lancaster in figure 2.6 below

becomes important because it incorporate the expansion of the role of the value

chain by means which the relationship and information management activities

become more effective by identifying value chain constraints.

Figure 2.6: Value chain structure and

process

Value Chain Management

Supply Chain Management

Relationship Management

Customers' Value criteria

less Customers' Costs of Acquisition

Product - Service Attributions

Value Delivery

Value Communication

Value production Assets & core

- inputs Value Competencies Value

- processes Proposition - required Objectives and strategy

- available

· Security

· Performance

· Aesthetics

· Convenience

· Economy

· Reliability

less

· Specification

· Search

· Transactions

· Operation

· Maintenance

· Disposal

· Core product

· Tangible product

· Augmentation

· Extended product

· Marketing logistics

· Transaction channels

· Physical distribution channels

· Benefits available

· Competitive advantage (s)

· Acquisition

costs

· Times to market

· Service

· Quality

· Risk

· Costs

· Partnerships

· Materials management

· Target

customers

· Internal

· value drivers

· activities

· costs

· External

· value attributes to be delivered

· ' relative value '

· Key success

factors

· Skills

· Ressources

· 'Corporate value'

· Profitability

· Productivity

· Cash flow

· Knowledge

· Performance

Information Management

Source: Adapted from Walters and Lancaster (2000:163)

35

Sutton (in Walters & Lancaster, 2000:162-3) proposes the

market mechanism as a means to coordinate activities. It is suggested that the

term "market co-ordination" be used for the situation in which specialisation

is separate and where the value chain comprises a series of sequential

individual activities under individual ownership. An alternative model is one

in which more than one organisation"... seeks to combine two or more stages

under single control and rely upon internal management to ensure

co-ordination". Sutton uses the conventional term "vertical integration" for

this structure. An organisation may also act as a contractor to co-ordinate the

other links in the value chain but relies on external agreements rather than

internal management.

The vertical co-ordination comprises individual organisations

having specific objectives but shared purpose (customer satisfaction) within

the value chain. According to Sutton (in Walters & Lancaster, 2000:162-3),

vertical integration has alternative structural options, namely breadth and

depth. Breadth occurs in companies that rely on co-ordination of some

activities while assuming ownership of others.

Sutton (in Walters & Lancaster, 2000:162-3) suggests

differentiation as breadth being the extent of co-ordination with vertical

integration and depth the activities that are combined into one activity, given

that the value chain is concerned with value maximisation and cost

optimisation. Therefore, the availability of economies of scale and scope is

important. These relate to the ability to specialise and gain cost advantages

and/or to offer a limited range of specialist products and/or services that

have significant impact on customer costs, for which much of the fixed costs

are shared.

2.7.5 Value nets

A traditional supply chain is designed to meet customer demand

with a fixed product line, relatively undifferentiated, one-size-fits-all

output and average service for average customers. In contrast a value net forms

itself around its customers, who are at the centre. It captures their real

choices in real time and transmits them digitally to other net participants.

36

Table 2.1: Key business design differences

Old supply chain New value net

· One size fits all

· Arm's-length and sequential

· Rigid, inflexible

· Slow, static

· Analogue

|

·

|

|

· Customer-aligned

· Collaborative and systemic

· Agile, scalable

· Fast-flow

· Digital

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Adapted from Bovet & Martha (2000:6).

According to Bovet and Martha (2000:2), a value net views

every customer as unique. It allows customers to choose the product/service

attributes they value most. The traditional supply chain manufactures products

and pushes them through distribution channels in the hope that someone will buy

them. In contrast, a value net begins with customers, allowing them to

self-design products and builds to satisfy actual demand. Thus, Bovet and

Martha (2000:2) describe a value net as a business design that uses digital

supply chain concepts to achieve both superior customer satisfaction and

company profitability. It is a fast, flexible system that is aligned with and

driven by new customer choice mechanisms. Therefore a value net is not what the

term `supply chain' conjures up. It is no longer just about supply, it is about

creating value for customers, the company and its suppliers. Nor is it a

sequential, rigid chain.

2.7.6 The e-business value chain

The e-business processes enable efficient and effective

collaboration between organisations, directly or through so-called

e-marketplaces. This means that responsibilities are shared between

organisational units of the collaborating organisations. The improvement of SCM

and CRM processes are key to enabling the organisation value chains (Kirchmer,

2004:25).

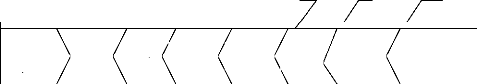

When the Porter value chain is considered and e-business

technologies are placed into the

framework, it gives an insight into the

reach of these technologies into the value activities. The

37

major enabler is the Internet and that is why the resulting

processes are called e-business processes, connected to entire networks of

processes across various organisations. Thus, the e-business value chain model

by Hooft and Stegwee (2001:49) in figure 2.7 below, is used to illustrate that

e-business can reach all activities of the organisation, and that some

applications cover multiple value activities. In this model, the linkages

already exist between activities; some of these linkages have been integrated

by using e-business technologies, ultimately providing a fully integrated

e-business process. By analysing the e-business value chain model, it helps the

organisation lower the costs and increase the value of activities.

Figure 2.7: The e-business value chain

Source: Adapted from Hooft & Stegwee (2001:49).

Porter (in Diana & Judith, 2003:242) examines the

Internet as it applies to the value chain as shown in figure 2.8 below. In this

depiction, Porter employed his well-known value chain model to examine

Web-based initiatives. Consequently, the focus is on strategy as it relates to

the value chain. The model therefore suggests the dimensions of operations,

technology, logistics and marketing as being potentially strengthened by the

adoption of e-commerce strategies.

38

Figure 2.8: Prominent applications of the Internet in

the value chain

Dissemination throughout the company of real-time inbound and

in-progress inventory data

Firm Infrastructure

· Web-based, distributed financial and ERP systems

· Online investor relations (e.g., information

dissemination, broadcast conference calls)

Human Resource Management

· Self-service personnel and benefits administration

· Web-based training

· Internet-based sharing and dissemination of company

information

· Electronic time and expense reporting

Technology Development

· Collaborative product design across locations and among

multiple value-system participants

· Knowledge directories accessible from all parts of the

organization

· Real-time access by R&D to online sales and service

information

Procurement

· Internet-enabled demand planning, real-time

available-to-promise/capable-to promise and fulfillment

· Other linking of purchase, inventory, and forecasting

system with suppliers

· Automated " requisition to pay"

· Direct and indirect procurement via marketplaces,

exchanges, auctions and buyer-seller matching

Real-time integrated scheduling, shipping, warehouse

management,

demand management and planning, and advanced planning and

scheduling across the company and its suppliers

Inbound Logistics

Web-distributed supply chain management

Integrated information exchange, scheduling, and decision making

in in-house plants, contract assemblers and components suppliers

Real-time availableto-promise and capable-to-promise

information available to the salesforce and channels

Operations

Real-time transaction of orders whether initiated by an end

consumer, a salesperson, or a channel partner

Automate customer-specific agreements and contract terms

Customer and channel access to product development and delivery

status

Collaborative integration with customer forecasting systems

Integrated channel management including information exchange,

warranty claims, and contract management

Outbound Logistics

Real-time inside and outside access to customer information,

product catalogs, dynamic pricing, inventory availability, online submission of

quotes, and order entry

Online sales channels including Web sites and marketplaces

Online product configurators

Customer-tailored marketing via customer profiling

Push advertising

Tailored online access

Real-time customer feed-back through Web surveys, opt-in/- out

marketing, and promotion response tracking

Marketing and sales

Customer self-service via Web sites and intelligent service

request processing including updates to billing and shipping profiles

Real-time field service access to customer account review,

schematic review, parts availability and ordering, work-order

Update,

and

service

parts manage-

ment

Online support of customer service representative Through e-mail

response management, billing integration, co-browse, chat, " call me now,"

voice-over IP, and uses of video streaming

After-Sales Service

Source: Adapted from Porter in Diana & Judith (2003:242).

For effective value chain reconfiguration, the process of

reconfiguring is necessary to an organisation's survival in a changing

environment (Normann & Ramirez, 1998:99). Thus, having an offering code

that enhances fit for potential value-creating activities between supplier and

customer is necessary. This is where the concept of leverage comes in.

According to Normann and Ramirez (1998:59), leverage explores

and exploits opportunities based

on better utilisation of the joint

resources of both parties, as well as those of subcontractors, partners

or

other suppliers as appropriate. Therefore, leveraging can take the form of

relieving and/or

39

enabling the customer. Both concepts concern the configuration of

activities as they are manifested in the relationship linking customer and

supplier; that is, in the offering.

2.8 ERP system and e-business: An evolving relationship

for value chain extension

In the 1990s, software developers developed ERP software, a

fuller "suite" of applications capable of linking all internal transactions.

Since then the use of ERP software has exploded, and some advocates claim that

it is the ultimate solution to information management. While traditional

production management information systems have focused on the movement of

information within an organisation, Web-based technology facilitates movement

of information from business to business (B2B) and from business to consumer

(B2C), as well as from consumer to business (Balls et al., 2000:2-3).

According to Balls et al., (2000:2-3), research groups such as

Forrester, Gartner and AMR all project incredible growth for e-business in the

first five years of the new century. Some analysts in Balls et al., (2000:2-6)

comment that in their rush to become an e-business, most organisations have

decided against implementing an ERP system. Balls et al., (2000: 4-6) have

discovered that some client companies are building e-business applications

while largely ignoring ERP development, hoping someone, someday will integrate

the back end. As a result, companies whose e-business applications have no

order-fulfilment and order-status capabilities either lack data or need to

recreate it.

E-business simply does not work without clean internal

processes and data. The choice, though, is not between developing e-business

solutions or implementing ERP. Clearly, both are necessary. According to Balls

et al., (2000:4-6), making ERP work most effectively in an e-business

environment means shedding old notions of ERP. One such notion is whether ERP

will always look the same. Balls et al., (2000:2-3) assert that ERP software in

the next few years will certainly not look like ERP software designed in the

1990s. The delivery of ERP functionality will also change. For instance, a

software vendor that today focuses on one front-end e-business application may

in the future build into its products a transaction engine component that can

then be attached to other organisations' front-ends. The other option is that

ERP vendors will successfully make products more flexible and less difficult to

implement, and they will either add e-business functionality or make their

systems more compatible with third-party front-end e-business products. Why is

this a

40

challenge for ERP vendors? Organisations use ERP software to

enable processes that confer a competitive edge. Consequently, e-business is

forcing ERP vendors to rethink their products' role within the enterprise. All

are in some way looking to broaden ERP functionality to incorporate front-end

technology and create trading communities through portals and joint ventures

with Web-based technology and other vendors.

For many organisations, ERP itself may be delivered over the

Web through business application outsourcing undertaken by application service

providers. In the future, it is clear that companies will work together in

extended value chains. Those that are able to plug their internal IS into the

information chain that parallels the physical goods value chain will prosper;

those that are not will fail. Successful organisations will be part of a

networked team of business partners dedicated to delivering customer value.

Very few (if any) organisations will be able to compete single-handedly against

such a team. The technology to "team" is available today, and strong teams are

already beginning to form. In short, together, e-business technologies (the

Internet, the Web, a host of e-enabling technologies) and ERP systems will

provide companies with new options for raising profitability and creating

substantial competitive advantage (Balls et al., 2000:7). Balls et al.,

(2000:7) realise that properly implementing e-business and ERP technologies in

harmony truly creates a situation where synergism is created. Web-based

technology puts life and breath into ERP technology that is large,

technologically cumbersome and does not always easily reveal its value. While

ERP organises information within the organisation, e-business disseminates that

information far and wide. ERP and e-business technologies supercharge each

other. The purpose of these new technologies (ERP and e-business) is to enable

the extended value chain.

2.9 The value chain selected and customised for the

purpose of this study

This study involves Porter's value chain, Walters and

Lancaster's value chain, the e-business value chain, the Scott value chain and

the customer-centric value chain as discussed at the beginning of this chapter.

The reasons for selecting these value chains respectively are given below.

· Porter's value chain model

Porter's value chain model is one of the foundation concepts on

which most ERP systems are built.

Even though IT has revolutionised it, the

concept remains an important tool for evaluation.

Therefore for this study

the model will be applied by comparing the generic modules and functions

41

of Porter's value chain with Axapta Microsoft software modules

and configuration as motivated in chapter 1.

· Walters and Lancaster's value chain

model

Walters and Lancaster (2000:178) point out that

identification of customer value criteria and an understanding of the key

success factors are necessary for creating both competitive advantage and

resultant success. Therefore value propositions become the means by which the

customer understands the value offer (typically made explicit as a series of

product/service attributes) and by which the value chain components assist in

the formulation, evaluation and decision on their value-adding contributions in

organisations. Walters and Lancaster (2000:178) view strategy as the

value-creating system itself in which members work together to create value.

Therefore, a key strategic task in the reconfiguration of value chain roles

falls under relationships in order to "mobilise the creation of value in new

forms and by new players". The model will be applied in this study to test

Axapta Microsoft software value chains in its roles, relationships and

leveraging mechanisms for the creation of value and its cost drivers for MNE

users.

· The e-business value chain model

With regard to the challenge of e-business in the value chain

system, it is the objective of this study to determine if Axapta attributes

have been incorporated in e-business mechanisms, which could extend the value

chain of an MNE. For its reason this model will be applied to indicate the

possibility of its use or otherwise.

· The customer-centric value chain

"The value of any product or service is the result of its

ability to meet a customer's priorities" (Slywotzky & Morrison, 1997:23).

Customer-centric thinking begins first with the customer and then moves,

ultimately, to the assets and core competencies. It literally reverses the

value chain so that the customer is the first link in the chain and everything

else follows (Slywotzky & Morrison, 1997:21). Thus, the customer-centric

value chain will be applied in order to analyse the Axapta Microsoft software,

to determine if it has been formulated according to the customer-centric

philosophy.

42

· Scott's value chain

There is now an increasing shift away from this departmental

view of competencies to managing the value chain holistically. The SBUs that do

well in a particular segment will ensure that the entire value chain works to

support their differentiating attributes. It is the ability of an organisation

to integrate all its departmental skills behind a single goal that gives it

decisive advantage over the competition (Scott, 1998:89). Thus, the value chain

model will be applied to analyse Axapta Microsoft software capability in its

relationship between a company's value and its SBUs.

The question can be asked whether Axapta software is based on

the value chain model and, if it is a value net with a leverage capability,

whether it has an impact on the effectiveness of an MNE's value chain in

fulfilling its requirements. The value chain models selected for this study, as

evaluative tools, will attempt to answer the above questions. This will be

debated further as part of the findings of this study in chapter 6, where

results will be put in relation to some of the hypotheses and objectives

formulated in chapter 1.

2.10 The value chain's system through ERP

integration

«The value chain's system integration is the process by

which multiple organisations with a shared market channel collaboratively plan,

implement, and manage (electronically as well as physically) the flow of goods,

services, and information along the entire chain in a manner that increases

customer-perceived value» (Balls et al., 2000-12). ERP systems facilitate

this integration, and as a structured approach, they optimise an organisation's

internal value chain.

According to Balls et al., (2000:82-4), a highly integrated

value chain creates greater value for the end-customer by delivering products

and services more efficiently and effectively. Within the industry the group of

organisations that carry out each step in creating and delivering products is

called the supply chain. Therefore the supply chain transforms into an

integrated value chain when it:

· Extends the chain all the way from sub-suppliers to

customers;

· Integrates the back-office operations with those of the

front office;

· Becomes highly customer-centric, focusing on demand

generation and customer service;

· Is proactively designed by chain members to compete as an

«extended organisation»; and

43

É Seeks to optimise the value added by information and

utility enhancing services.

The tangible benefits of system integration are inventory

reduction, personnel reduction, productivity improvement, order management

improvement, financial-close cycle improvements, IT cost reduction, procurement

cost reduction and revenue/profit increase, etc. On the other hand, the

intangible benefits are information visibility, new/improved processes,

customer responsiveness, standardisation, flexibility, globalisation and

business performance. Consequently, value chain integration allows real-time

synchronisation of supply and demand and enables support of an organisation in

its efforts to become part of an extended organisation, beyond electronic

supply chain management. This pushes MNEs to develop collaborative business

systems and processes that can span across multiple organisation boundaries.

2.11 The impact of IT in the value chain

system

In his introduction of the value chain theory, Porter makes

no reference of IT as a backbone to support the mechanism behind the process.

However, later Porter and Millar (1985:150) acknowledge the importance of IT by

mentioning that this technology «is transforming the nature of products,

processes, companies, industries, and even competition itself. Until recently,

most managers treated IT as a support service and delegated it to electronic

data processing departments. Now, however, every company must understand the

broad effects and implications of IT and how it can create substantial and

sustainable competitive advantages».

The revolution of IT, especially computers, came to change

the traditional value chain. In the study of Walters and Lancaster (1999:646),

Brow comments that the changes in and convergence of information and

communication technologies are the significant issues to highlight. Brow

illustrates changes in value chain structure by arguing that the role of

outsourcing has become more important in order to achieve the effectiveness of

the value delivery. Brow further emphasises the role and impact of information

management as an important feature that provides a co-ordinating activity. In

addition, Evans and Wurster (1997:71) write that: «the changing economies

of IT threaten to undermine the established value chains in many sectors of the

economy, requiring virtually every company to rethink its strategy - not

incrementally, but fundamentally». Evans and Wurster refer to this

phenomenon as the "deconstruction of the value chain". Ghosh (1998:130) refers

to it as

44

"pirating of the value chain" and explains that companies are

forced to risk the relationships in their physical chains in order to compete

in the electronic channel.

IT is spreading through the value chain system and it is

performing optimisation and control functions as well as judgmental executive

functions (Porter & Millar, 1985:151). Indeed, IT has had a revolutionary

effect on competitive scope in the way in which it facilitates local, regional,

national and international operations and co-operation. Truly the role and

impact of an ERP system as an integrative and a strategic IT tool challenges

the way businesses used to operate, and consequently supports the value chain

operation to act efficiently and globally for MNEs to gain competitive

advantage. With regard to the above view, the question is: Is Axapta software a

value chain system with IT mechanisms, which facilitate the integration and the

co-ordination of other ERP system applications? This question will be answered

in chapter 6.

2.12 Conclusion

«A business is profitable if the value it creates

exceeds the cost of performing the value activities» (Porter & Miller,

1985:152). Therefore, an organisation succeeds by ensuring that the entire

process necessary to deliver a good or service is attuned to achieving the

single goal of competitive positioning in the market. This requires

co-ordination across the entire value chain, even if certain pieces of it are

more critical than others (Scott, 1998:89). Thus, assert Day, Georges, Rebstein

and David (1997:33), the attractiveness of a certain industry or product market

depends upon how the economic value created for certain customers is shared

throughout the value chain.

The analyses of the value chain concept in this chapter have

focused on the assessment of the different value chains, and the linkage of all

activities within them for competitive advantage. A competitive advantage

requirement is that a viable number of buyers end up preferring the

organisation's product offering because of its perceived «superior

value». Superior value is nearly always created in either one of two ways:

(1) by offering buyers a "standard" product at a lower price, or (2) by using

some differentiating technique to provide a "better" product that more than

offsets the higher price it usually carriers (Thompson & Strickland,

1987:134). In this study, it was determined that:

· IT plays a key role in the value chain in terms of

the co-ordination of the different activities to create a product and the

delivery of the service in an efficient manner to satisfy customers.

45

· The value chain approach could indeed help to

measure the strength of an organisation's value

chain system, as well as of

a product's value chain, using ERP software, i.e. Axapta Microsoft.

· The ERP system is based on the value chain concept,

which supports the observation that it is a value chain system too.

Unfortunately, most ERP architecture of the past did not incorporate IT as one

of its core competencies. Therefore current ERP systems must be incorporated

with IT mechanisms, such as e-business technologies, to facilitate integration

and relationship within the value chain system.

· Based on the qualitative study of the ERP concept, an

ERP system as a value chain system becomes an evaluative tool and IT instrument

to evaluate ERP software (i.e. Axapta, SAP, Oracle, Aruba and others) attribute

and specification integrative status in its relationships to support

activities, strengths and ERP modules and applications.

The analysis of an organisation's value chain through a

formal value chain model, as introduced in this chapter, highlights the

linkages between the organisation's primary activities and support activities,

isolating both efficient and inefficient activities. By capitalising on the

efficient linkages and improving inefficient ones, organisations can increase

efficiency, lower costs and create value. Therefore, the surplus value created

through the achievement of efficiency translates directly into competitive

advantage for organisations pursuing a cost leadership strategy. In addition,

through the use of value chain analysis, organisations can identify the

attributes of products and/or services which customer's desire, resulting in

the creation of offerings that address these customer needs and desires.

Organisations are successful in differentiating their products and/or services

when they have a competitive advantage, which in turn, creates value and,

hopefully, profit for the organisation (Porter, 1998: 40).

However, the theories behind the value chain make the concept

impossible to be universally applicable owing to differing organisation

structures and objectives, which means that the value chain system must be

configured and applied differentially to every type of MNE. The value chain

architecture is therefore a unique tool, which is crafted for every type of

organisation, especially for MNEs where the architecture is very complex

because of the broad operation at different sites.

In chapter 6, the value chain theory assessed in this chapter

will indicate whether the Axapta

46

software value chain architecture, configuration and business

functional activities fulfil the requirements and help MNEs to craft their

value chain. It will be determined whether Axapta software as a value chain

system and the ERP system do in fact meet the requirements of a general global

ERP system model and the MNEs' value chain system for competitive advantage.

The next two chapters will be dedicated to ERP systems as an

associate value chain system in order to show how it relates technically to the

value chain configuration and architecture, since most ERP system software is

built upon it.

47

|