CHAPTER 3: AN OVERVIEW OF ERP SYSTEMS

3.1 Introduction

Expanding the discussion of the value chain theories in the

previous chapter, this chapter focuses on ERP systems and their relation to the

value chain concept. The purpose of this chapter specifically is to define and

analyse the concept of an ERP system, its background as well as its benefits,

characteristics, advantages and disadvantages. This is followed by a discussion

of the integrating role ERP plays in IT, its modules, global configuration and

architecture. The factors of strategic evaluation of ERP software, including a

brief overview of the selection and key factors associated with the success and

failure affecting the system during and after implementation, are also

investigated. The evaluation of the system will provide the technical

background theory, allowing the researcher to compare Axapta Microsoft software

under the magnifying glass (in chapter 4) with the theories assessed on value

chain architecture and configuration related to ERP systems in chapter 6, to

develop the overall qualitative part of this study.

3.2 The background of ERP systems

During the 1960s the focus on manufacturing systems was on

traditional inventory control concepts. Most of the software was limited

generally to inventory based on traditional inventory processes, owing to the

need for manufacturing operations. Since then manufacturing systems have moved

to material requirement planning systems, which translated the master planning

schedule to build for the end items into time-phased net requirements for the

sub-assemblies, components and raw materials planning and procurement. In 1975,

MRP grew from a simple tool to become MRPII.

However, according to Chung, Snyder and Gumaer (in Chin,

Hsiung & Ming, 2004:235) the shortcoming of MRPII in managing a production

facility's orders, production plans and inventories, and the need to integrate

these new techniques led to the development of a rather more integrated

solution called an ERP system. The ERP system vanquishes the old stand-alone

computer systems in finance, human resources, manufacturing and the warehouse,

replacing them with a single unified software program divided into software

modules that roughly approximate the old stand-alone systems. Therefore, Baki

and Cakar (2005:75) position an ERP system as an integrated enterprise-wide

system, which automates core corporate activities such as manufacturing, human

resources,

48

finance and supply chain management. With these benefits, an

organisation achieves many improvements such as easier access to reliable

information, elimination of redundant data and operations, reduction of cycle

times and increased efficiency, hence reducing costs.

3.3 Defining the concept of an ERP system

ERP system software links divisions or departments together

through the supply chain, enabling anyone to look into the warehouse, for

example, to see if an order has been shipped. What is important to note is that

most vendors of ERP software are flexible enough that some modules can be

installed without buying the whole package. Therefore many organisations

implementing an ERP system for the first time install the ERP software modules

of finance or human resources, leaving the rest of the functions for later

(Baatz, Koch & Slater: available online). An ERP system works essentially

at integrating the whole business information function, allowing organisations

to effectively manage their resources of people, materials and finance. The

system combines both business processes and IT into one integrated solution in

the organisation, which MRP and MRPII were unable to provide. Thus, asserts

Aladwani (2001:266), the ERP system is an integrated set of programmes that

provides support for core organisational activities. Blasis and Gunson

(2002:16-7) state that an ERP system is a tool that grafts a solution for human

resources, finance, logistics etc., and eventually to SCM and CRM. This

provides a closer relation to partners with the expansion of the customer base

from large organisations to small and medium, and from a wide industry offer by

encompassing service as well as manufacturing industries due to the Web-enabled

technologies as shown in figure 3.1 below.

Figure 3.1: Integrated modules in ERP

solutions

Enhanced ERP Web ERP

ERP basic modules

· Finance

· Logistics

· Manufacturing

· Human resources

· etc.

· SCM

· CRM

+

Web-enabled

technologies

+

49

Source: Adapted from Blasis & Gunson (2002:17).

For many users, an ERP system is a «do it all» that

performs everything from sales orders to customer service. Others view it as a

data bus with data storage and retrieval capability. In addition, Gardiner,

Hanna and LaTour (in Shehab, Sharp, Supramaniam & Spedding, 2004:8) point

out that an ERP system can be used as a tool to help improve the performance

level of a supply chain network by helping to reduce cycle times. Boykin (in

Shehab et al., 2004:8) argues that an ERP system is the price of entry for

running a business and for being connected to other organisations in a network

economy to create B2B and electronic commerce. ERP brought about the myriad of

interconnections, which ensure that any other unit or department within the

organisation can obtain information in one part of the business. This makes it

simpler to see how the business as a whole is doing. ERP systems help people

eliminate redundant actions, analyse data and make better decisions (Sweat in

Gupta, 2000:115).

An ERP system is the information pipeline system within an

organisation which allows the organisation to move internal information

efficiently so that it may be used for decision support inside the organisation

and communicated via e-business technology to business partners throughout the

value chain (Balls et al., 2000:186). In addition, Siriginidi (2000:378)

defines ERP as an integrated suite of application software modules, providing

operational, managerial and strategic information for organisations to improve

productivity, quality and competitiveness.

From the above definitions, it can be concluded that an ERP

system can be regarded as an integrated organisation-wide software package that

uses a modular structure to support a broad spectrum of key operational areas

of the organisation. It provides a transactional backbone to the organisation

that allows the capture of basic cost and revenue related movements of

inventory. In so doing, ERP affords better access to management information

concerning business activity, showing actual sales and cost of sales in a

real-time fashion (Adam & Carton, 2003:22). The full installation of ERP

software across an entire organisation connects the components of the

organisation through a logical transmission and sharing of commonalties.

Therefore, in this interface the data such as sales becomes available at any

point in the business, and it courses its way through the software, which

automatically calculates the effects of the transaction on areas such as

manufacturing, inventory, procurement, invoicing and bookkeeping (Balls et al.,

2000:12). Clemons and Simons

50

(2001:207) state that ERP is a term used to describe business

software that is multifunctional in scope, integrated in nature and modular in

structure. Indeed, ERP systems are designed for multisite, multinational

companies, which require the ability to integrate business information, manage

resources and accommodate diverse business practices and processes across the

entire organisation. In support of the above view, Wood and Caldas (in Adam

& Carton, 2003:22) found in their survey of 40 organisations that had

implemented ERP that the main reason for doing so was the need to "integrate

the organisation's processes and information".

3.4 The general model of an ERP system compared to a

value chain system

According to McAdam and McCormack (2001:116), the concept of

integration within the functions of an organisation can be represented by

Porter's value chain model as depicted in figure 2.1. Porter looked at the

organisation as a collection of key functional activities that could be

separated and identified as primary activities (inbound logistics, operations,

outbound logistics, marketing and sales, and service) or support activities

(infrastructure, human resource management, technology development and

procurement). Porter arranged these activities in a value chain. Maximising the

linkages between the activities increases the efficiency of the organisation

and the marginal availability for increasing competitive advantage or for

adding shareholder value. Integration occurs between the primary activities in

each value chain, and is enabled by the support activities. It can also take

place between activities in different organisations, and in some cases, the

support activities also share resources. Thus, ERP systems aid the integration

of these various functional processes within the organisation's value chain.

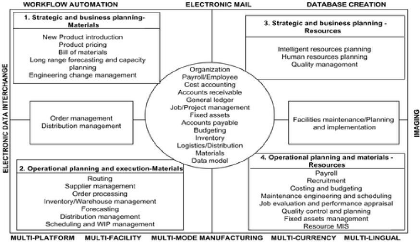

Figure 3.2 below represents the general model of ERP systems and execution,

integrated functionality and the global nature of present-day organisations in

the different functional activities format of Porter's value chain model in

figure 2.1.

In figure 3.2, the circle at the centre represents the

entities (organisation, payroll/employees, cost accounting, general ledger,

job/project management, budgeting, logistics and materials, etc.) that

constitute the central database shared by all functions of the organisation.

The border represents the cross-enterprise functionality (multiplatform,

multimode manufacturing, electronic data interchange, workflow automation,

database creation, imaging, multilingual, etc.) that must be shared by all

systems. The cross-organisation borders would be multifaceted, act as

multifacilities and represent the capability required by the organisation to

compete and succeed globally. It is important for the system's total solution

to support multiple divisions or organisations under a

51

corporate banner and seamlessly integrate operating platforms

as the corporate database that results in integrated management information

(Siriginidi, 2000:379-80). The co-ordination performed by information system

integration (ERP system) within the organisation's value chain enables more

views to be shared, employee awareness to be broadened and customer

expectations to be tracked and met (Bhatt, 2000:1331)

Figure 3.2: The general model of an ERP

system

Source: Adapted from Siriginidi (2000:380).

The emphasis is further placed on the fact that the heart of

any ERP exercise materialises in the creation of an integrated data model.

Approaching it holistically, the ERP and execution model and its flexible set

of integrated applications keep operations flowing efficiently. It should be

looked upon as the acquisition of an asset, not as expenditure. An ERP system

as a business tool seamlessly integrates the strategic initiatives and policies

of the organisation with the operations, thus providing an effective means of

translating strategic business goals to real-time planning and control. In

order to achieve the integration of all the basic units of the business

transaction, ERP systems rely on large central relational databases. This

architecture represents a return to the

52

centralised control model of the 1960s and 1970s (Stirling,

Petty & Travis, 2002:430), where access to computing resources and data was

very much controlled by centralised IT departments. Therefore, ERP

implementations are an inherent part of a general phenomenon of centralisation

of control in large businesses back to a central corporate focal point (Clemons

& Simons, 2001:207).

3.5 The role and benefits of an ERP system

According to Ming, Fyun, Shihti & Chiu (2004:689-90), ERP

systems have developed beyond their originally design intended to provide

organisations with integrated, consistent and concurrent information that is

available across the organisation. Integrated with electronic data interchange,

it is used to streamline business processes in vertical markets, giving

organisations the control and management of their resources. Furthermore, ERP

systems provide a platform for integrating applications such as executive

information system data mining, SCM, CRM and e-commerce systems. The real

benefits of ERP systems currently are associated with the arrival of Web

applications, which facilitate ERP systems to extend to electronic markets

integrated with supply chains through B2B e-hubs. It further also extends to

partners to integrate their own operations with other functions and to manage,

monitor and execute all transactions in real time. An ERP system is considered

to be the price of entry into B2B, e-market and other organisations in a

network economy.

Davenport (in Adam & Carton, 2003:24) shows the

paradoxical impact of an ERP system on organisation and culture. ERP systems

provide universal, real-time access to operating and financial data, and allow

the organisations to streamline their management structures, creating flatter,

more flexible and more democratic organisations. ERP systems also involve the

centralisation of control over information and the standardisation of

processes, which are qualities more consistent with hierarchical, command and

control organisations with uniform cultures. Indeed, ERP systems help

organisations in cross-organisation application integration, where the

organisations can link their ERP systems directly to the disparate applications

of their suppliers and customers. Therefore, such integration benefits the

organisation in the following ways, which have been emphasised by Gupta

(2000:115-6):

· Web-based procurement application;

53

· The incorporation of the Internet in its applications;

and

· The outsourcing of ERP applications where the major

vendors of ERP are offering outsourcing programs to small and medium

organisations that are unable to implement the system themselves

Furthermore, an ERP system links processes, people, suppliers

and customers together, and it helps a business to globalise its operations,

expand its supply chain and customer relations base while simultaneously

integrating it with e-commerce. Adam and Carton (2003:22) highlight some of the

benefits achieved by the organisations looking to harness the tight global

co-ordination afforded by ERP systems, which are:

· Streamlining global financial and administrative

processes;

· Global lean production models with rapid shifting of

sourcing, manufacturing and distribution functions worldwide in response to

changing patterns in supply and demand; and

· Minimising excess manufacturing capacity, while reducing

component and finished goods inventory.

Thus, Spathis and Constaninides (in Ming et al., 2004:690)

position an ERP system as a tool which can be used to integrate manufacturing

and marketing functions to determine the competitiveness and profitability of

organisations and the production of real-time data, which is shared across the

organisation, resulting in the integration and the automation of business

processes, and the real benefit of integration and its ability to share

information with customers and suppliers within the organisation. The core

competency of ERP systems within an organisation can be expanded to vertical

networks. Sharing information is what transforms ERP systems into the backbone

of a supply chain, and not just the backbone for internal networks. The

benefits are magnified from the same internal advantages with better

co-ordination and optimisation by eliminating external uncertainties (Ming et

al., 2004:690).

3.5.1 The advantage and disadvantage of an ERP

system

According to Gupta (2000:115-16), the advantages and

disadvantages of ERP systems are as follows:

54

Advantages

· Y2K compliance;

· Ease of use;

· Integration of all functions;

· Online communication with suppliers and customers;

· Customisation;

· Improvement of decision-making due to the availability of

timely and appropriate information;

· Improved process time;

· Feasibility of administering pro facto control

on the operations;

· Internet interface; and

· Reduction of planning inaccuracies.

Disadvantages

· Organisational resistance to change, which may be

high;

· Changeover, which may take a long time causing cost

overruns;

· Data errors, which can be carried throughout the system;

and

· Maintenance is costly and time-consuming.

3.5.2 The characteristics of an ERP system

According to Hyung, Nam-Kyu & Sang (2003:197-200), the

major characteristics of an ERP system are an enterprise-wide system that

covers all the business functions and information resources, integrated

database, built-in best industry practice, packaged software and open

architecture. In addition, ERP enables reduction of system development time,

flexibility, standardisation of workflow and effective business planning

capability. Therefore, ERP is characterised by the aspects of classification of

information exchange, sharing and information service as shown in table 3.1

below.

55

Table 3.1: Characteristics of an ERP system

Classification Characteristics of ERP system

Information interchange EDI connection

Open system and globalisation

Information sharing One fact, one place

(integrated task system)

Standard business process model, GroupWare connection and

executive information system function

Information service End-user computing and

integrated database

Source: Adapted from Hyung et al., (2003:200).

It must further possess some key characteristics and features to

qualify as a true business process integration solution. These features are:

· Flexible. An ERP system should be flexible in order to

respond to the changing needs of an organisation. Client/server technology

enables ERP systems to run across various database servers through open

database connectivity.

· Comprehensive. An ERP system is able to support a variety

of organisational functions and is suitable for a wide range of business

organisations.

· Modular and open. An ERP system should have open

system architecture, meaning that any module can be interfaced or disconnected

whenever required without affecting the other modules. It should also support

multiple hardware platforms for organisations having a diverse collection of

systems.

· Beyond the organisation. A good ERP system is not

confined to the organisational boundaries, but can support online connections

to other business entities outside the organisation.

· Simulation of reality. An ERP system can simulate real

business processes on the computer.

· Multiple environments required. For ERP, most

businesses must maintain multiple environments in order to achieve uptime

requirements: development/test, promote-toproduction, highly available

production, and disaster recovery.

56

3.6 ERP system: The hub of an MNE

Davenport (in Adam & Carton, 2003:22) states that

organisations collect, generate and store vast quantities of data which is

«spread across dozens or even hundreds of separate computer systems, each

housed in an individual function, business unit, region, factory or

office». Therefore, ERP systems have a huge impact on business

productivity due to the workload of reeking, reformatting, updating, debugging,

etc. When management is relying on information from incompatible systems to

make decisions, instinct becomes more important than sound business rationale.

Thus, ERP systems are positioned as a tool designed for multisite,

multinational organisations, which require the ability to integrate business

information, manage resources and accommodate diverse business practices and

processes across the entire organisation. In addition, Balls et al.,

(2000:30-1) note that an ERP system provides consistency of information across

a global organisation and integrates the following:

· Resource planning, which includes forecasting and

planning purchasing and material management, warehouse and distribution

management, product distribution, accounting and finance. By providing timely,

accurate and complete data about these areas, ERP software helps a company to

assess, report on and deploy its resources quickly, while also focusing on

organisational priorities. For example, a company can assess its total cash

position globally for a large supplier who may also be a customer. All too

often, bills are paid to suppliers who are also customers and who are owing

more than they are owed.

· Supply chain management, which includes understanding

demand and capacity, and the scheduling of capacity to meet demand. By linking

disparate parts of an organisation with ERP, more efficient schedules can be

established that optimally satisfies the organisation's needs. This reduces

cycle time and inventory levels, and improves a company's cash position.

· Demand chain management, which includes handling

product configuration (quotes, pricing and contracts, promotions and

commissions). By consolidating information with ERP, contracts can be better

negotiated, pricing can be established to consider the total organisation-wide

position, and sales offices can be better assessed, rewarded and managed.

· Knowledge management, which includes creating a data

warehouse, a central repository for the organisation's data, performing

business analysis on this data, providing decision support for organisation

leadership and creating future customer-based strategies. These activities

comprise

57

a management information system, which facilitates the making

of appropriate business decisions. In this capacity, ERP evolves from a

transaction-processing engine into a true distiller of information. Data

warehousing can become a powerful tool for corporate executives and managers

only if it is fed with data that is consistent, reliable and timely.

3.6.1 The modules of an ERP system

ERP systems generally include some of the most popular

functions within each module, but the names and numbers of modules in an ERP

system provided by various software vendors may differ. A typical system

integrates all these functions by allowing its modules to share and transfer

information freely, centralising information in a single database accessible by

all modules. The model of an ERP system, according to Siriginidi (2000:380) and

shown in figure 3.2 above, includes areas as such as:

· Finance (financial accounting, treasury management,

organisation control and asset management);

· Logistics (production planning, materials management,

plant maintenance, quality management, project systems, sales and

distribution);

· Human resources (personnel management, training and

development and skills inventory); and

· Workflow (integrates the entire organisation with

flexible assignment of tasks and responsibilities to locations, positions,

jobs, groups or individuals).

In addition, other functionality requirements stipulated by

Sarkis and Sundarraj (2000:201) include:

· Business planning and material requirement planning;

· Marketing and sales (sales and distribution, inventory

and purchases);

· Resource flow management (production scheduling, finance

and human resources management);

· Works documentation (work order, shop order release,

material issue release and route cards for parts and assemblies), shopfloor

control and management and costing;

· Manufacturing and maintenance; and

· Engineering data control (bill of materials, process plan

and work centre data).

58

In a fully integrated ERP system, these activities are

accomplished by utilising the five tightly integrated modules of finance,

manufacturing, logistics, sales and marketing, and human resources, as briefly

discussed next (Balls et al., 2000:31).

· Finance

ERP software significantly reduces the cost of financial

record keeping. The consistency of ERP system data provides improved

information for analysis and a seamless reconciliation from the general ledger

sub-ledgers. The data is updated in real time throughout the month, and a basis

is created for linking operational results and the financial effects of those

results. With ERP, a physical transaction cannot be booked without the

resulting financial effect being shown. This visibility of activities across

finance and operations allows operational managers to better understand the

effects of their decisions. The company's financial department is better

equipped to provide decision support to corporate leadership, create strategic

performance measures and engage in strategic cost management.

· Manufacturing

With ERP software's ability to explicitly link the

operational and financial systems, organisations can easily determine how

operational causes equal financial effects. The software provides a consistent

set of product names in a central product registry, a consistent way of looking

at customers and vendors, integration of sales and production information, and

a way to calculate availability of products for sales, distribution and

materials management. An integrated ERP system also enables better order to

production planning by linking sales and distribution to materials management

production planning, and financials in real time, real-time visibility of

customer orders and customer demand, and modelling of anticipated orders. With

ERP, sales opportunities turn into orders based on past performance

information, stock can be adjusted nearly instantly and detailed manufacturing

resource planning can be performed daily.

· Logistics

ERP integrates distribution more tightly with manufacturing,

sales and financial reporting, thereby

enhancing reporting of future

performance indicators as well as past performance measures. The

software

provides an integrated basis for managing the signals that support the

distribution

59

environment necessary to meet twenty-first century customer

desires and demands. ERP technology supports strategic purchasing and

"materials only" costing rather than standard costing and aligned performance

indicators, rather than traditional indicators that measure functional silos

and support customer-driven, low-cost operations. ERP also supports

cross-functional, process-driven, customer-focused logistics and

distribution.

· Sales and marketing

ERP software enhances an organisation's sales efforts in a

number of ways. Performing profitability analyses requires real-time data for

costs, revenue and sales volumes. With an ERP system, the company can perform

profitability analysis, showing profits and contribution margins by market

segment. With ERP software, it is also possible to design sophisticated pricing

procedures that include numerous prices, discounts, rebates and taxes

considerations. The sales organisations can use ERP to project much more

accurate delivery dates for orders. In an e-business environment, customers

will be able to receive much more accurate delivery date information over the

Web, and, when the ERP system is properly linked to an e-business front-end,

look into the company's finished-goods and work-in-process inventories, as well

as materials availability to determine how quickly an order can be filled.

· Human resources

An ERP system supports an organisation in its human resource

planning, development and remuneration areas. It provides an integrated

database of personnel (employed or contracted), maintains salary and benefits

structures, supports planning and recruiting, and keeps track of reimbursable

travel and living expenses. ERP does payroll accounting for a wide variety of

individual national requirements and allows a company to centralise or

decentralise the payroll function by country or by legal entity. ERP records

individual qualifications and requirements used for resource planning, enhances

career and succession planning, and co-ordination of training programmes, and

maximises time management, from planning to recording and controlling time,

including shift planning, time exception reporting and time reporting for cost

allocation where staff charge their time to specific cost objects such as

projects or service orders.

60

3.6.2 ERP system package

According to Shehab et al., (2004:361), although an ERP

system is a pure software package, it embodies ways of doing business. In

addition, an ERP system is not just a pure software package to be tailored to

an organisation, but rather an organisational infrastructure that affects how

people work. It "imposes its own logic on an organisation' s strategy, and

culture" (Davenport, Lee & Lee in Shehab et al., 2004:361). ERP has

packaged best business practices in the form of a business blueprint. This

blueprint could guide organisations from the beginning phase of product

engineering, including evaluation and analysis, to the final stages of product

implementation.

In total there are about a hundred ERP providers worldwide,

e.g. SAP-AG, Oracle, JD Edwards, PeopleSoft and Baan, SSA, BPCS, Inertia Mover,

QAD, MFG and PRD. The systems have a few common properties and they are all

based on a central, relational database, built on client/server architecture

and consist of various functional modules as indicated above. Among the most

important attributes of an ERP system, according to Shehab et al., (2004:60-5),

is its ability to:

· Automate and integrate business processes across

organisational functions and locations;

· Enable implementation of all variations of best business

practices with a view towards enhancing productivity;

· Share common data and practices across the entire

organisation in order to reduce errors; and

· Produce and access information in a real-time environment

to facilitate rapid and better decisions and cost reduction.

All ERP system packages need to be customised and

parameterised to suit the needs of individual organisations. However, the

system packages touch many aspects of a company's internal and external

operations. Consequently, successful deployment and use of ERP systems are

critical to organisational performance and survival.

3.7 Global ERP system configuration

Davenport (in Adam and Carton, 2003:24) estimates how much

uniformity should exist in the way

ERP does business in different regions or

countries. The differences in regional markets remain so

profound for most

organisations that strict process uniformity may actually be

counter-productive.

61

A configuration table enables a company to tailor a

particular aspect of the system to the way it chooses to do business.

Organisations can select, for example, the functional currency for a particular

operating unit, or whether they want to recognise product revenue by

geographical unit, product line or distribution channel (Adam and Carton,

2003:24). Therefore, Davenport (in Madapusi & D'souza, 2005:8) warns that

organisations must remain flexible and allow regional units to tailor their

operations to local customer requirements and regulatory structures. In

practical terms, in Europe, ERP projects are more complex than in North America

because of diverse national cultures, which influence organisational culture

and make successful implementation of MNEs' ERP solutions difficult.

However, in the study of Adam and Carton (2003:23-4),

Krumbholz states that failure to adapt ERP packages to fit the national culture

leads to projects which are expensive. Therefore, MNEs face a choice between

using their ERP as a standardisation tool or preserving (or rather tolerating)

some degree of local independence in software terms. The resulting

standardisation in business processes allows companies to treat supply and

demand from a global perspective to consolidate corporate information resources

under one roof, shorten execution time, lower costs in supply chains, reduce

stock levels, improve on-time delivery and improve visibility and product

assortment with respect to customer demand. Thus, Davenport (1998:126)

recommends a type of federalist system, where different versions of the same

system are rolled out to each regional unit. This raises its own problems for

the company, i.e. deciding on what aspects of the system need to be uniform and

what aspects can be allowed to vary (Horwitt, 1998:1).

3.7.1 Alignment between ERP system configuration and

international strategy

Madapusi and D'souza (2005:8) suggest that successful ERP

systems tend to be those that are closely aligned with the types of

international strategies that the organisation has chosen to adopt. Therefore,

it is important that management understand the interrelationship between ERP

system configuration and the international strategy of the organisation.

Madapusi and D'souza use the two constructs to develop a framework explaining

how management at an MNE can use it to align ERP configuration with the

international strategy of the organisation. According to Markus, Tanis and Van

Fenema (2000:42), the prevailing wisdom on ERP system configuration is that

management has to address three issues, namely:

62

· ERP software configuration;

· ERP information architecture; and

· ERP system rollout.

ERP software configuration

The findings of Koch (2001:68) indicate that an ERP system

should be configured hierarchically at four levels in an organisation:

· Organisation level. There are four types of

organisation-level ERP configurations that international organisations can

adopt, namely single-financial/single-operation,

singlefinancial/multi-operations, multi-financials/single-operation, and

multi-financials/multi-

operations.

· The system level. At this level, business activities such

as logistics, financials and operations are implemented as modules.

· Business process level. At this level, the focus is on

the customisation of user profiles, parameters and business processes.

· Customisation level. This involves custom-designed

modifications and extensions to ERP application.

ERP information architecture

According to Clemons and Simons, and Zrimsek and Prior (in

Madapusi and D'souza, 2005:10), there are three commonly accepted ways to

configure ERP information architecture:

· Centralised architecture. This refers to an organisation

that has achieved high levels of standardisation of data and commonality of

business processes.

· Distributed architecture. This refers to the organisation

that has a strong history of autonomous business units.

· Hybrid architecture. This refers to the organisations

that want to leverage their global supply chains and at the same time localise

their products and services, and prefer hybrid architectures that are less than

completely centralised or distributed.

63

ERP system rollout

Parr and Shanks (2000:7) comment that when configuring ERP

systems, organisation's management must deal with the challenges of ERP system

rollout. Parr and Shanks' (2000:8) research findings suggest that system

features such as the number of sites and users, the level of complexity of the

business processes, the level of customisation, the mix of ERP modules chosen

and the existence of legacy system could be critical in determining the success

of an organisation's rollout strategy. These factors can lead to varied

approaches to ERP system rollout.

However, there is good support for two general approaches to

ERP system rollout that were popularised in the mid-1990s by Mabert, Soni and

Venkataraman (2003:237) and Markus et al., (2000:45), namely the "big bang"

approach and the phased implementation approach. The organisations that prefer

a "big bang" approach to ERP implementation roll out a set of ERP application

modules across their worldwide operations simultaneously. A well-planned big

bang rollout enables the organisation to rapidly implement and derive benefits

from a core set of integrative application modules and processes. By contrast,

the phased implementation of application modules takes place at national level,

with integration primarily through financial reporting modules. Although phased

implementation is time-consuming, it involves less risk compared to the big

bang approach, and tends to involve less re-engineering efforts. The phased

implementation component of the rollout allows the organisation to learn, adapt

and explore alternate courses of action (Scott and Vessey in Madapusi &

D'souza, 2005:14).

3.7.2 Types of international strategies

Businesses typically adopt one of three types of international

strategies, namely multinational, global, or transnational as briefly discussed

next (Madapusi and D'souza, 2005:11).

· Multinational strategy

One of the primary objectives of a multinational strategy is

to build sensitivity and responsiveness to differing national environments.

Organisations that pursue this strategy offer differentiated products and

services to satisfy the local needs of their national units. These

organisations derive most of their value from downstream value chain

activities, such as marketing, sales and service, and often clone their value

chains in multiple national markets.

64

· Global strategy

The constant search for global efficiencies and cost

considerations drives the actions of organisations that choose a global

strategy. These organisations leverage economies gained through product

standardisation and global sourcing. Control and co-ordination of activities

are typically concentrated at the organisation's headquarters.

· Transnational strategy

Organisations that adopt a transnational strategy focus on

local responsiveness and global efficiency - a "best of both worlds" approach.

Organisations that pursue this strategy recognise that their competitive

advantage accrues from location advantages and economic efficiencies. The

theoretical underpinnings of ERP systems discussed above relate to the

configuration and international strategy viewed in ERP configuration,

architecture and rollout, with international strategy alignment for

organisations that use a multinational strategy only, together with global and

transnational strategies.

3.7.3 ERP systems for organisations that use an MNE

strategy

Organisations that adopt an MNE strategy are often structured

as decentralised federations that grant strategic and operational latitude to

national units. Because headquarters focuses primarily on the bottom line, it

treats each national unit as a profit centre and prefers governance mechanisms

that favour standardised outputs. Mutual adjustment is encouraged through

informal headquarter-national unit relationships. Not surprisingly,

organisations that have strongly independent national units also have

independently run IT operations, as stipulated by Bartlett and Ghoshal,

Jarvenpaa and Ives, Karimi and Konsynski (in Madapusi & D'souza,

2005:12).

· ERP software configuration and MNE

strategy

At organisation level, organisations that implement an MNE

strategy tend to select a multifinancials/multi-operations logical structure

for their ERP. At system level, an organisation tends to have a system

independent of but linked to headquarters through financial reporting modules.

At business process level, the system is based on detailed levels. At

customisation configuration level, the system is based on high levels.

65

· ERP information architecture and MNE

strategy

Organisations using an MNE strategy typically opt for

distributed information architectures with stand-alone local databases and

application, the configuration of local hardware requirements, the involvement

of maximum use of a local area network (LAN) and minimal use of a wide area

network (WAN). In this ERP architecture, each local unit is autonomous.

Headquarter linkage occurs primarily through financial reporting structures

(Clemons & Simons, 2001:207-10). The national units are allowed

considerable latitude in determining their own hardware requirements. Network

bandwidth requirements are restricted to managing and co-ordinating local

operations. WAN bandwidth requirements are minimal because of limited

headquarter-national unit interactions.

· ERP system rollout and MNE strategy

The preferred rollout option would be a phased implementation

of application modules at national level, with integration primarily through

financial reporting. Organisations that adopt a multinational strategy face

unique challenges. The near absence of centralised control and standardisation

often results in multiple and varied ERP configurations across national units.

Application functionality can also vary across multiple platforms, making it

difficult to obtain an integrated/holistic view of crucial business data.

Industry best practices, which are embedded in typical ERP vendor packages,

have been found to enhance control and integration over worldwide operations.

However, because an ERP system is independently developed, organisations must

invest in customised integration code to facilitate data alignment (Madapusi

& D'souza, 2005:12).

3.8 Strategic factors for the evaluation and selection

of an ERP system

For an ERP system to meet the requirement of the

organisation's value chain system, it needs to be evaluated in terms of its

modules and functionality relating to the organisation objectives. ERP

encompasses all the traditional functional areas of a business, in addition to

the manufacturing focus of MRPII systems. A typical set of business functions

supported by an ERP system is summarised below based on Dykstra and Cornelison,

and Olinger (in Sarkis & Sundarraj, 2000:206).

· Business planning includes the vision and the mission of

the organisation, and the strategies needed to accomplish them.

66

· Organisation performance measurement systems help

the organisation to determine how well they are doing, to continuously improve

and manage the organisational processes. These systems include performance

information on the internal and external supply chain.

· Decision support helps in the management of the internal

and external supply chain, which may

include optimisation, simulation,

heuristic, quantitative and qualitative modelling approaches.

· Marketing and sales include sales analysis and forecast

of the demand for products in the

business plan, sales order management,

customer maintenance and billing information system.

· Manufacturing includes the functions of a traditional

MRPII system (capacity planning, material resource planning, inventory

management, bills of material).

· Finance and accounting include payroll, product costing,

accounts payable and receivable, general ledger and asset management

information systems.

· Engineering includes changes made by the engineering

department with respect to routings, bills of material, quality control,

machining programs, product designs, maintenance information, etc.

· Human resources include a listing of employees, their

status within the organisation and benefits owed to them by the company.

· Purchasing includes supplier, performance,

product sourcing, in-bound logistics tracking and materials management

information systems. These systems can provide direct linkage to the upstream

external supply chain.

· Logistics help the outbound logistics management of

the organisation with control and linkage to external customers or other

divisions of the same organisation such as warehouses. These systems provide

significant linkage to the downstream external supply chain.

· After-sales service is meant to aid the customers

after the sale of a product. Information concerning service parts inventory,

such as locations and sources, product reliability, and other performance

measures would be needed in this system. Its inclusion is important because it

is one of the more forgotten factors.

· Information systems are a function central to the

management of ERP. Data accuracy, maintenance, user and performance information

is all-important to this function. They ensure that the value chain operates

efficiently and effectively with respect to information sharing, acquisition

and delivery.

67

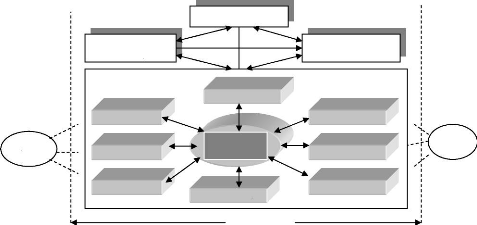

Sarkis and Sundarraj (2000:205) integrate the evaluation

factors mentioned above into one conceptual model as shown in figure 3.3 below.

The control factors (business planning, decision support and organisation

performance measurement system) of the internal supply chain are placed over

the various internal supply chain factors. The various internal supply chain

factors are composed of the remaining processes and functions as described

above (factors, especially the engineering and purchasing, are close to the

suppliers, although they are not the only ones with linkages to suppliers). In

a similar vein, customers are linked to marketing, logistics and after-sales

service. In the middle of figure 3.3, linking all these internal supply chain

factors is the IS factor (ERP). It is clear that there is a two-way

relationship with IS to show that it is meant to integrate all the various

factors to each other, and that they are allowed and able to communicate with

one another.

Figure 3.3: The conceptual model of ERP system linkages

with supply chain factors

Business Planning

Enterprise

Performance

Measurement

System

Decision Support

MRP II

Engineering

Marketing

Suppliers

Purchasing

Information

System

DRP/ Logistics

Human Resources

After - Sales Service

Finance and Accounting

Internal Supply Chain

Customers

Source: Adapted from Sarkis and Sundarraj (2000:207).

68

3.8.1 Selection of an ERP system

For a global ERP rollout, the MNEs that want to implement the

system need to know if the ERP software selected is designed to work in

different countries. A good selection will allow a global organisation to be

able to control and co-ordinate its various remote-operating units with

accurate and real-time information provided by ERP software, since some of the

system software has the ability to integrate the more remote subsidiaries into

corporate practice and allows the sharing of information in standard format

across departments, currencies, languages and national borders. ERP software

product purchasing is a high cost and risky process. It is therefore critical

to make this project successful for an organisation. To be successful, the

right solution should be selected and the selected software package must be

used effectively (Baki & Cakar, 2005:76). Tanner (in Neves, Fenn &

Sulcas, 2004:45) argues that correct ERP selection is vital to minimise

financial risk and uncertainties about the software and its compatibility with

the organisation's business structure.

If a poor choice of software system is made, it can adversely

affect the organisation as a whole, even jeopardising its very existence. This

highlights the need for performing adequate levels of research into making the

correct choice of software and preparing the organisation for its introduction

(Neves et al., 2004:45). Bingi, Sharma and Godla, as well as Horwitt (in Adam

& Carton, 2003:22) note that ERP systems could be used to provide a

«common language» between units. In addition, Baki and Cakar

(2005:76) assert that a selected ERP solution should be able to support

decision-making. Mabert et al., (in Baki & Cakar, 2005:76) argue that if

the right ERP solution is selected, it can be an excellent decision support

tool that will provide a competitive advantage. In addition, Somers and Nelson

(2001:2939) stress that the choice of package involves important decisions

related to budgets, time frames, goals and deliverables that will shape the

entire project. Choosing the right ERP solution that best matches the

organisational information needs and processes is critical to ensure minimal

modification and successful implementation and use. The wrong software will not

fit the organisation's strategic goal or business.

This necessitates the involvement of a proper selection

mechanism, evaluation and strategic technical planning model tool such as the

value chain approach discussed in chapter 2 and the methodical approach

formulated in chapter 7 of this study. In fact, software and hardware

characteristics are critical for ERP implementation success, and conducting a

requirement analysis

69

in the early stage of project implementation and thoroughly

reviewing a number of hardware/software solutions that might result in the

system that better fits the users' requirements are essential (Petroni,

2002:333). Baki and Cakar (2005:77-81) recommend the importance and usage of a

benchmark selection criteria checklist when selecting the package. Elements

such as functionality, technical aspect, cost, service and support, vision,

system reliability, compatibility with other systems, and ease of customisation

must be taken into account. Other factors to be considered are:

· Market position of the vendor, better fit with

organisational structure, domain knowledge of the supplier, references of the

vendors and fit with parent/allied organisation systems; and

· Cross-module integration, implementation time,

methodology of the software and consultation.

3.8.2 Methodology of an ERP system

According to Stirling, Petty and Travis (2002:430-5), the

methodology has seven decisions points, each relating to a different outcome.

The methodology is supported by a series of questions to assist users in making

appropriate decisions. The goal of the methodology in the analysis of ERP has

to provide a structured approach to the problem of meeting systems requirements

within a specific department or overall within the organisation. Therefore,

once an ERP system database is based on a proprietary package selection, and in

new business requirement identification, this is then subject to a series of

tests in decision point framework questionnaires to assist users in tailoring

their system.

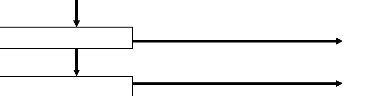

The methodology framework below in figure 3.4 guides the user

through a structured decision-making process, and the decisions at each point

require judgement and experience. As a result, a series of questions were

devised to be applied at each decision point, once the methodology has been

developed. Stirling et al., (2002:431) state that it is crucial to undertake

some forms of validation. This can be achieved through a series of structured

interviews with systems development professionals.

70

The methodology proposed by ERP vendors should be effective

and should not include unnecessary activities for the organisation. In every

stage of the methodology, it should be determined what activities will be

carried out how, when and with which resources.

Figure 3.4: Outline of the methodology

No

No

No

Change core

system

Yes

Change business process

Purchase

appropriate module

Yes

Use

spare field

Yes

Yes

Business requirement

Does the business requirement

represent a radical

change?

Should the process be change?

Can an available module be used?

Can spare fields in the core systems

be

utilised?

No

Yes

No

Yes

Use subsidiary system

Modify core system

Can a subsidiary system be used?

Must the core be modified?

|

No

|

Yes

|

Requirement for data transfer

|

|

Linked system

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Use an independent system

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No requirement for data transfer

Source: Adapted from Stirling et al., (2002:436).

3.9 The implementation of an ERP system

The acquisition and implementation of ERP systems are very

effort-intensive processes. An

empirical analysis of the implementation

process in European organisations revealed mean

71

implementation costs of 1.5 million Euros and a mean

implementation time of 13.5 months (Buxmann & Konig in Bernroider &

Tang, 2003:7). In addition, high risks are also involved in every ERP project.

The far-reaching structural changes following ERP software implementation can

be disastrous. Many ERP implementations fail to achieve their corporate goals

(Buckhout, Frey & Nemec, 1999:118). It can be assumed that the failure of

the system project implementation can often be attributed to the major mistakes

made in the early stages of the ERP life cycle prior to the implementation

process.

According to Esteves and Pastor (in Bernroider & Tang,

2003:5), a typical life cycle of an ERP system covers six different stages,

namely adoption decision, acquisition, implementation, use and maintenance,

evolution and retirement. Conducting a requirement analysis in the early stage

of the project implementation and thoroughly reviewing a number of

hardware/software solutions might result in a system that better fits the

users' requirements. MNEs that implement a global ERP solution frequently find

themselves in a position where the changes are imposed rather than designed.

Blasis and Gunson (2002:6) assert that IT software projects often fail and ERP

implementation projects do not escape this tendency. However, ERP solutions do

not fail primarily for technical reasons. Further analysis of the factors of

success or failure of ERP implementation projects indicates that it is

primarily the implementation effect of an organisation, the workplace and the

individuals at work, which yields a positive or negative result.

The main implementation risks associated with ERP projects

are related to change management and business re-engineering those results from

switching to ERP software. To overcome users' resistance to change, Aladwani

(2001:273) recommends that top management study the structure and needs of the

users and the causes of potential resistance among them, and deal with the

situation by using the appropriate strategies and techniques in order to

introduce ERP successfully and evaluate the status of change management

efforts. In addition, for many organisations, the real challenge of ERP

implementation is not the introduction of new systems, but the fact that they

imply "instilling discipline into undisciplined organisations." Because of its

modularly, ERP software allows some degree of customisation (i.e. selection of

modules best suited to the business's activities). However, the system's

complexity makes major modifications impracticable. The very integration

afforded by the interdependencies of data within the different modules of the

system means that changes in configuration could have huge knock-on affects

throughout the system.

72

From a management perspective, the nature of ERP

implementation problems includes strategic, organisational and technical

dimensions. ERP implementation involves a mix of business process change and

software configuration to align the software with the business processes.

Ho, Wu and Tai (2004:235) state that numerous scholars and

experts have proposed explanations for the failure of the implementations.

These include inadequate resources, a lack of support from upper management, a

lack of promotion, poor integration of business strategies, inappropriate

choice of tactics and failure to establish the necessary IT infrastructure

within organisations. Together with problems of existing system complexity,

system integration and organisational process transparency, business process

re-engineering, exterior consultation, the role of suppliers, user training and

system customisation all complicate matters.

3.9.1 Factors affecting the implementation

process

The factors specific to ERP implementation success include

re-engineering business processes, understanding corporate cultural change and

using business analysts on the project team. Bancroft, Seip and Sprengel

(Shehab et al., 2004:367) provide the following critical success factors for

ERP implementation:

· Support from top management;

· The presence of a champion;

· Good communication with stakeholders; and

· Effective project management.

Nah, Lau and Kuang (Shehab et al., 2004:369) researched the

critical factors for initial and ongoing ERP implementation success and

identified 11 factors:

· ERP teamwork and composition;

· Change management programmes and culture;

· Support from top management;

· Business plan and vision;

· Business process re-engineering with minimum

customisation;

73

· Project management;

· Monitoring and evaluation of performance;

· Effective communication;

· Software development, testing and troubleshooting; and

· Project champions, and appropriate business and IT legacy

systems.

In a study focusing on the complexity of multisite ERP

implementation, Markus et al., (2000:43) claim that implementing ERP systems

could be quite straightforward when organisations are simply structured and

operate in one or a few locations. However, when organisations are structurally

complex and geographically dispersed, implementing ERP involves difficult,

possibly unique, technical and managerial choices and challenges.

3.9.2 A strategic approach to ERP

implementation

The are two different strategic approaches to ERP

implementation, according to Baatz, Slater and Koch (available online). In the

first approach, an organisation has to re-engineer the business process to

accommodate the functionality of the ERP system, which means changes in

long-established ways of doing business and reviewing important people's roles

and responsibilities. This approach takes advantage of future ERP releases,

benefits from the improved processes and avoids costly irreparable errors. The

other approach is the customisation of the software to fit the existing

process, which slows down the project, introduces dangerous bugs into the

system and makes upgrading the software to the ERP vendor's next release

excruciatingly difficult, because the customisations will need to be developed

and rewritten to fit with the new version. Since each alternative has

drawbacks, the solution can be a compromise between complete process redesign

and massive software modification. However, many companies tend to take the

advice of their ERP software vendor and focus more on process changes (Shehab

et al., 2004:8).

3.9.3 Cost of ERP implementation

ERP implementation involves two kinds of costs: quantifiable

costs that lend themselves to a discounted cash flow analysis, and human factor

costs that are unquantifiable but very real. Quantifiable costs fall into five

categories: hardware, software, training and change management, data

conversions, and re-engineering. Other costs to the organisation involve

non-quantifiable costs

74

to the governance structure. An ERP installation affects both

the power structures within the organisation and the company's usual

decision-making process (Balls et al., 2000:53). The benefits of ERP system

implementation are both quantifiable and qualitative. The quantifiable benefits

are increased process efficiency, reduced transaction costs due to the

availability and accuracy of data and the ability to turn that data into

meaningful information, reduced information organisation costs in hardware,

software and staff necessary to maintain legacy systems, and reduced staff

training costs over time as people become more «change ready». The

qualitative benefits include a more flexible governance and organisational

structure, and a workforce ready to change and focus more on high-value-added

tasks and easy capitalisation on opportunities as they present themselves

(Balls et al., 2000:54).

3.10 Conclusion

There is different ERP software in the market, consisting of

many modules. Since every organisation is unique, before implementing an ERP

system, the organisation must choose the most suitable solution to meet its

needs and thus enable it to gain a competitive advantage. It was argued in this

chapter that this could be achieved by viewing ERP as a strategic IT tool, and

conducting a proper analysis before the adoption and implementation process.

Verville and Halingten (2002:207) highlight the importance of the acquisition

process of an ERP system as it allows examination of all the dimensions and

implications (benefits, risks, challenges, costs, etc.) prior to the commitment

of formidable amounts of money, time and resources.

The literature study of the ERP concept in this chapter has

revealed that ERP software itself is a value chain system related to the value

chain approach. Therefore, the theory of the ERP system discussed in this study

is becoming an evaluative tool relating to the value chain theory that can be

used to analyse and evaluate ERP software (Axapta Microsoft solution software)

components and attributes, modules and functionalities.

75

|