NEWCASTLE UNIVERSITY

THE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION, COMMUNICATION AND

LANGUAGE SCIENCES

MASTER OF EDUCATION

INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT &

EDUCATION

Primary Education and Entrepreneurship in East Africa:

A case study of private schools for the poor in

Kibera (Kenya)

Eric Keunne Nodem

089108996

Supervisor: Dr

Pauline Dixon

September

2010

SCHOOL OF EDUCATION, COMMUNICATION AND LANGUAGE

SCIENCES

I certify that all material in this

Master's dissertation

which is not my own work, has been identified

and that no

material in included which has been submitted

for any other

award or qualification.

Signed:

Date: Friday

3rd September 2010

|

This dissertation

is dedicated to my Supervisor Dr Pauline Dixon who helped me throughout these

years to keep on smiling in spite of the abyss in which I was

plunged...

|

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Holding this precious piece of work at hand at this particular

moment still gives the deep impression that I am not yet awake from the dream

in which I have been plunged into for the past two years. Indeed reaching the

completion point of my master degree has not been easy at all and I humbly feel

that I have definitely made a great step ahead in the accomplishment of my

goals. All the way from Cameroon my home country to the UK via Belgium, the

path has been dotted with so many obstacles. These unbearable moments in my

life could have led to a total surrender of the project, but yet I was still

able to stand and «fight for my future» as Dr Dixon would say.

It is not only my responsibility but my utmost pleasure to

extend my first feeling of heartfelt and warm gratitude to all the scholars and

people who have in one way or the other one contributed to make this dream come

true. My tremendous gratitude is extended to Dr Pauline Dixon who has been my

first support as well as an unquantifiable resource from day one at Newcastle

till date. As my personal advisor, supervisor and pathway leader of the

International development and education master's programme, Dr Dixon has

nurtured me indefatigably with perseverance, hardworking, patience and

particularly hopes for a better future ahead. Dearest Pauline, may you find in

the significance of these words the true and sincere recognition of my

gratitude. You have helped me to realise this dream and i shall always be

indebted to you.

My gratitude and recognition go to the Master of Education

staff of Newcastle University for their enormous support in accompanying all

the students throughout the academic year. I hereby acknowledge and salute the

job carried on by the program director, the program secretary, all the

lecturers and staff of the EG WEST CENTRE. All my friends and colleagues from

the programme have equally played a great role in my social wellbeing at

Newcastle in such a way that omitting to mention their contribution will

definitely look pretty unfair. From various origins at the very beginning, we

all emerged gradually and finally became one single group. Wherever they may

be, I should like thank each and every one of them. On a particular note, I

would like to single out Mr George Mikwa of the Kenyan Independent Schools

Association (KISA) for the unstinting and unconditional assistance in the

completion of this work. Through him and thanks to Dr Dixon, we were able to

carry out this research in Kibera. He acted as our main resource person in

Kenya and was very helpful in collecting our data on the field and further

channelling these at the EG WEST Centre, Newcastle University.

Furthermore, I will like to extend my sincere and warm

gratitude to Professor Augustin, Bame Nsamenang, of the university of

Yaoundé and Director of The Human Development resource Centre (HDRC)

Bamenda, Cameroon. He initiated and guided my ways in the area of research

right from my early beginnings at the Teacher's training college in Bambili,

Cameroon and has always encouraged me to pursue my academic dreams with

conviction and enthusiasm, in spite of the difficulties that could hamper my

success. Many thanks Prof.

Finally, I extend my sincere thanks to Dr Nguendjio of the

Teacher's Training college in Cameroon, friends, family who have always trusted

and encouraged me. Without the tremendous support of all the people mentioned

above as well as so many others, this dissertation could not been as more

meaningful as it is to me now.

ABSTRACT

Primary Education and

Entrepreneurship in East Africa:

A case study of private schools for the poor in

Kibera

The dissertation describes and analyses the study of primary

education and entrepreneurship in Kibera, one of the largest slums in East

Africa. The research is carried out to establish the contribution of the

private educational sector in the global campaign of Education for All (EFA) in

Kenya. With the euphoria created by era of free primary education which has

taken place in most African countries in the early 2000's and the negative

impressions that have been noted as a result of this embracement , this study

set out to critically appraise the role played by private schools owners in

the provision of «quality education». The research which is a case

study uses information from 20 school owners, 25 pupils and 25 teachers from

selected schools in the slum of Kibera to answer the research question and sub

questions.

The dissertation commences with a general introduction in

which the scene is set up through background information and specific details

concerning the focus and the aim of the study. It equally discusses in a

succinct way the motives and reasons behind the exploration of private schools

in Africa. The review of literature provides a general picture of recent and

ongoing debates on private schools for the poor especially in Africa; this is

followed by related discussions on entrepreneurship and the development of the

continent. The overall method used for the study is then addressed in the third

chapter and this opens an avenue for the examination and analysis of the data

collected through the research instruments. At this point every question is

critically explored and the results being commented accordingly. All the

respondents' answers in addition to relevant documentation are given serious

concern in the quest of a response to the main question of the research and to

determine the general satisfaction expressed for the investments in education.

The summary and suggestion section concludes the whole study.

The findings suggest that even in the context of free primary

education, many parents and pupils still prefer the private schools in spite of

the fact that these schools charge fees. Some of the pupils taking part in the

research who have been in the past enrolled in government schools deplore the

overcrowded classrooms, teachers' absence and lack of attention which is

rampant in government schools. The private schools owners, who in the majority

are familiar with the Kenyan educational system, mentioned some of the above

points as the motivations for setting up their own schools. Two recurrent

points were «inadequate schools» in the slum and the desire to focus

on HIV/AIDS orphans and socially excluded children. Both teachers and pupils

actually expressed their overall satisfaction with the investments except for

issues like infrastructures, facilities and salaries for the case of teachers.

It was found that the information about the regulations governing the opening

of private schools in Kenya is flawed given that few entrepreneurs barely knew

what they were. The action of the Kenya Independent Schools Association (KISA)

is considered extremely important for the development of the sector and

suggestions are given at the end in favour a potential support for the

association. The private schools in Kibera and certainly elsewhere in Africa

are considered a crucial partner in the achievement of Universal Primary

Education given their potential. It therefore would seem quite bizarre not to

value the contribution of the educational entrepreneurs in the overall process

of education and above all the development of Africa.

Contents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

4

ABSTRACT

6

1.1Presentation of the topic

13

1.2 Focus and aim of the Study

14

1.3 Why the Private educational Sector?

15

1.4 Why Kenya (Kibera)?

16

1.5 Why look at Entrepreneurship?

17

1.6 Why mixed methods?

18

1.7 The dissertation

19

Chapter Two - Literature Review

22

2.1 Introduction

22

2.2 Private education in Africa

23

2.2.1 Free Primary Education and Private school for

the poor in Sub Saharan Africa

23

2.2.2 Critics of private school for the poor

27

2.3 Entrepreneurship and development in Africa

28

2.4 The Kenyan Independent School Association

(KISA) and the Development of Private School for the Poor

30

2.5 Summary

32

Chapter Three - Methodology

33

3.1 The research methods of the study

33

3.1.1 Theoretical framework

33

3.1.2 Research method used and description of data

collection

35

3.1.3 Target population and sampling

38

3.1.4 Reliability and Validity of the research

39

3.2 Permission and Ethics

40

3.3 Conducting the research in Kibera

41

3.4 Limitation of the study

42

3.5 Data presentation and Analysis

42

3.6 Conclusion

43

Chapter Four - Analysis

45

4.1 Introduction

45

4.2 Background

45

4.2.1 School and school owners

46

4.2.2 The Slum of Kibera

49

4.3 Motivations for Investment in the field of

Education

52

4.3.1 Lives within the community

52

4.3.2 Inadequate schools in the area

52

4.3.3 Focus on orphans, poor and vulnerable

children

54

4.3.4 Profit motive

55

4.3.5 Equity

57

4.3.6 Regulations of private schools in Kenya

61

4.4 Have these schools suffered from the

government's introduction of 'Free Primary Education (2003)' in terms of

enrolment?

63

4.5What is the satisfaction level of entrepreneur's

investments as perceived by pupils and teachers?

66

4.5.1 Pupil Satisfaction

66

4.5.2 Teacher satisfaction

74

4.6 Factors identified as the major gaps in private

provision

83

Chapter Five - Conclusion, Summary and the Way

Forward

86

Bibliography

93

Appendices

99

Appendix A- Letter of permission

99

Appendix B- SCHOOL OWNER QUESTIONNAIRE

100

Appendix C- PUPILS' QUESTIONNAIRE

102

Appendix D- Teacher Questionnaire

104

Appendix E- INTERVIEW ON THE BUSINESS OF

EDUCATION

110

Tables of Figures

Figure 1: Year in which school was opened

47

Figure 2: Age of school owner

48

Figure 3: School ownership type

49

Figure 4: A view o the slum of Kibera

49

Figure 5: Number of adult and children living in

the family home

50

Figure 6 Monthly fees

55

Figure 7: Number of girls in the 20 schools this

year

59

Figure 8: The number of boys in the 20 schools

60

Figure 9 Teachers' gender

60

Figure 10: First year Enrolment

65

Figure 11: Current enrolments

65

Figure 12 - The Rating of the Class teacher's

ability in their subject

69

Figure 13 - The rating of the teacher's punctuality

for lessons

69

Figure 14 - The rating of the teacher's attendance

at school

69

Figure 15: Teachers' fairness for students

70

Figure 16 - The Rating of the school buildings

70

Figure 17- Rating of the school facilities

71

Figure 18 - Rating of English lessons correlated

with English scores

72

Figure 19- Rating of maths and maths scores

72

Figure 20 - English results by school

73

Figure 21 - Kiswahili means plot by school

73

Figure 22: Teachers' age

74

Figure 23: salaries' satisfaction

76

Figure 24: Teachers' salaries

76

Figure 25: Irregular salary payments.

77

Figure 26: Holidays' satisfaction rate

78

Figure 27: Satisfaction with the work

environment

79

Figure 28: Satisfaction with facilities

80

Figure 29: Satisfaction with the school

infrastructure

81

List of tables

Table 1: School owners

47

Table 2: School owner

48

Table 3: Mum has a job

51

Table 4: Father's job

51

Table 5: The school offers scholarships for

orphans

56

Table 6: The school offers scholarships for

outstanding students

56

Table 7: Orphans' financial support

58

Table 8: Girls in school

59

Table 9: Boys in school

59

Table 10:Teacher's age

74

Table 11: Teachers' educational level

75

Table 12: Teachers' salaries

76

Table 13: Social status in the community

78

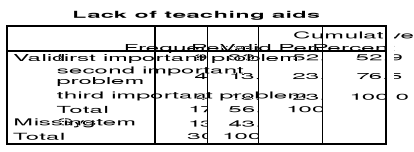

Table 14: First important problem

82

Table 15: Second important problem

82

Table 16: Third important problem

83

Chapter One: Background and Introduction

1.1Presentation of the

topic

The increasing queries and support

for primary education in Africa in the perspective of achieving Universal

Primary Education (UPE) by the year 2015, has been for some time at the centre

of many concerns both at national and international levels. In spite of

commendable strategies and reforms adopted by governments, scholars,

educational specialists, international agencies and donors from conferences

held in Jomtien (1990) and in Dakar (2000), general reports about primary

education in Africa are still alarming. The general consensus typically agrees

that the demand for education at all levels especially in Africa and Asia has

greatly outpaced supply. (Karmokolias et al 1997:4)

This dissertation's main focus is

to study primary education in east Africa and to establish related development

of educational entrepreneurship in Kenya and their contributions to one of the

most important Millennium Development Goals (MDG), which is making basic

education accessible to all through Universal Primary Education campaigns. In

the light of information gathered through research instruments, the study

discusses variables of the trend which is currently being observed in

developing countries: That of the mushrooming of private schools catering for

the poor and the socially excluded especially in slums and remote areas of

Africa Tooley et al 2007, Watkins 2000). Moreover it sets to find out the

entrepreneurs' motivations for setting private schools in slums, the impact of

their investment on the development process of their communities as well as it

critically analyses teachers and pupils satisfaction on private schools in

Kibera, one of the largest slums in East Africa. A review of literature on

private education and entrepreneurship in Africa has been covered at this

effect so as to enable a good understanding of the topic and relevant

scientific approaches to the theme.

The study gives an interesting picture of private schools in

Kibera and the efforts undertaken by school entrepreneurs to render the quality

of these schools better. The pupils and parent's heart of this slum seem to be

beating for private schools in spite of the Free Primary Education initiated in

Kenya in the year 2003. However, some shortcomings have equally been noted

especially at the infrastructural and financial level. Nonetheless, the private

schools in Kenya and elsewhere in Africa are playing a key role in forging

ahead basic education for all especially for the poorest.(Tooley et al 2008)

This research has benefited from a logistic support of the EG

WEST centre, Newcastle University and strong collaboration from its board

members as well as we have been able to get in direct touch with private school

entrepreneurs in Kenya thanks to George Mikwa, the president of the Kenya

Independent Schools Association (KISA).

1.2 Focus and aim of the

Study

In the perspective of understanding and addressing issues

related to primary education and Entrepreneurship in East Africa, the following

main research question constituted the central starting point:

`How and why do private school entrepreneurs contribute to

education for all in Kenya?'

Further, the main question was segmented into four sub areas.

This structure will provide analysis of the data to answer the overall thesis

question through the following sub questions:

· What are the entrepreneurs' major motivations for

investment in the field of education?

· Have these schools suffered from the government's

introduction of 'Free Primary Education (2003)' in terms of enrolment?

· What is the satisfaction level from their

investment as perceived by pupils and teachers?

· What factors could be identified as the major gaps

in this type of provision?

To cover all these questions, specific areas of investigations

were chosen and appropriately explored with close respect to many critics'

point of view to this type of provision (Watkins 2000, Lewin 2007, Rose 2006).

These specific areas ranged from entrepreneurs motivations for setting up

private schools in Kibera, actions taken to improve the quality of their

provision including the facilities offered in the teaching process in the

selected schools, to the study of the prevailing investment climate of Kenya.

Hence, a great importance was given to various opinions expressed concerning

the satisfaction level of direct beneficiaries of this investment, which are

pupils and teachers.

The identification of the major gaps in the private schools

provision equally formed part of the research and an analysis of pupils' tests

scores was equally carried in order to establish the correlation between the

overall satisfaction expressed and the achievements in these schools.

1.3 Why the Private

educational Sector?

This thesis focuses on the private sector because it is felt

that it's contribution to the advancement of education on the African continent

in enormous and have not been given appropriate consideration from educational

stakeholders, governments and donors. Many scientific works have been done on

private educational provision in the developing world and some are still under

research. All the reports note that there is a mushrooming of private schools

catering for low income families across Africa. The review of the literature,

making the second chapter of this thesis points out some of these arguments.

Based on these, it may appear that private schools in Africa are much more

preferred by the target audience to the detriment of government schools.

Several reasons given to consolidate this trend are likely related to

governments' inability to provide quality education in the developing

countries. Teachers' absence, lack of motivation, distance schools, overcrowded

classrooms, underground fees; these are some of the reasons behind the massive

return observed in private schools of Africa and across other developing

countries.

On its own, the private sector seems to be doing well.

Existing literature depicts a mitigating picture on this form of provision. On

one hand ,a set those advocating the merits of private schools for the poor

championed by Tooley and Dixon and on the other hand, another set of scholars

condemning to the lists extend the efforts done by private schools in the

Universal primary Education campaign. This set of scholars is headed by Lewin,

Pauline Rose and Watkins.

It then appears very challenging and exciting to carefully

analyse the positions of all these scholars in the light of effective research

so as to be able to come out with precise information on the role played by the

private sector in fostering education for All (EFA) especially in Africa where

many western efforts towards achieving development have up till date failed.

1.4 Why Kenya (Kibera)?

The approach given to the study has chosen the slum of Kibera

in Kenya for many reasons. First of all Kenya seem to be in the spot light

since it has been chosen as model of development in terms of educational

provision in Africa by many world leaders, influential politician and pop

stars. The declaration of the former US president, Bill Clinton actually

contributed a lot to fuel curiosity on the typical case of this country. In an

interview given to an American Television, the latter said he said the person

he most wanted to meet was president Kibaki of Kenya «because he abolished

school fees» which «would affects more lives than any president had

done or would ever do...»1(*). The declaration preceded actions from other

institutions. In fact, some financial donation from the World Bank and the

British government of worth $55m and £20m respectively were publicly

announced, in support to the Free Primary Education Campaign.

Secondly, the Free Primary Education campaign was launched in

Kenya in the year 2003 with the aim of covering the educational needs of the

population. This was to be a specificity of the new elected administration

headed by president Kibaki and had as focus all the government schools. Based

on past research in this country and current ones under research at the EG West

centre by James Stanfield and others, we were curious to find out if the

political and media propaganda surrounding the project had had the merit to be

so much highlighted. We equally wanted to know if the astronomical budget

allocated at this effect couple with international aid had boosted the

educational sector of Kenya.

Finally, Kibera from developmental perspectives is the biggest

slum in East Africa with a population estimated between 220,000 to 250,000

inhabitants living together in a perimeter of

2.3 And 2.5 sq Kilometres. It was felt that a study in such

area would depict a true picture of how poor people educational priorities and

which choice they make in fulfilling these priorities.

1.5 Why look at

Entrepreneurship?

Many economists have highlighted the role that entrepreneurs

and entrepreneurship could play in responses to poverty and social instability

on the continent. They argue in a great majority that private investment is the

only way out of Africa's miasma and underdevelopment and that the sector's

economic potential and social contribution needs to be re evaluated and given

strong regulatory support from African governments. It is suggested that in the

perspective of boosting the continent's development, investment should be done

in the field of agriculture, manufacturing, education, health care,

telecommunication, and infrastructure (Ayittey 2007).

However the prevailing investment environment in Africa seems

not to be encouraging enough and has been for ages now at the centre of many

observations (Ayittey 2007, Elkan 1988, Boettke 2007).

Back on the field of education, the existing literature that

investment is not a new phenomenon in Africa. Private schools did exist in

Africa long time ago and there has been a growing desire for more investment in

the field. This desire, as observed in the research has many motivations. The

case study of private schools in Kibera; where there is an incredible growing

number of populations, is just a picture of that desire for investment all over

the continent. However, critics as well governing bodies such as UNESCO and

OXFAM deplore that private schools entrepreneurs are geared towards profit

making and as such cannot claim to be offering quality service to the

population. The study of entrepreneurship in this case equally set out to

determine if this assertion in worthy of credibility.

1.6 Why mixed methods?

The case study approach in conducting the research in Kenya

required specific techniques of data collection. We thought that the study

would benefit from a mixed method in order to gather as much information as

possible from several angles, but equally to compare the results of the

investigations through the answers obtained with different techniques. Hence,

questionnaires, interviews, documentation were appropriately used at this

effect. Many scholars such as Creswell (2003) have valued this scientific

approach especially in social sciences as it enables the researcher to perform

a triangulation with the data collected.

The integration of quantitative and qualitative methods for

this study therefore provides us with so many advantages. It enables us to

understand clearly the motivations behind entrepreneurs' investments in private

schools in Kibera which is a captivating point in appraising the mushrooming of

private schools in Africa. Further it gives a picture of what the investment

climate in most African countries actually look like. Finally with these mixed

methods, we are able to evaluate the satisfaction level of the beneficiary

people involved in the educational business.

Above all, this multi- strategy approach provides us with

general information concerning the contribution of private schools

entrepreneurs in educational provision in Africa. Using this approach, the

overall procedure warrants and conveys to us a sense of rigour of the research

itself and this is quite useful in clarifying the nature of our intentions or

accomplishments. (Bryman 2006:98)

1.7 The dissertation

The answers to the research questioned mentioned above have

provided us with an avenue for understanding the strong motivation behind

investment in primary schools in East Africa and the related prevailing

investment climate. These answers have to an extent covered the focus and aim

of this study which set out to assess the contribution of private schools

entrepreneurs in educational provision on the continent. Several points of

views of advocators and non advocators of the private school system were taken

into account in the overall process of analysing the information obtained

through data collection. Hence the research plan was divided into five major

chapters and their content though structurally independent was interrelated and

all linked to the main research question.

The first chapter aimed at bringing the general information to

our topic, thus setting the scene for a thorough understanding of the thematic

approach to the research. It did give a rationale for the study as well as it

explained the reasons for focussing on the private sector and entrepreneurship

in Kenya (Kibera).

Chapter two reviews past and ongoing research on private

schools in Africa with foci on private schools in poor area. The priority here

is given to current trends on the growth of private schools in Africa and the

impact on the educational process in the global campaign against illiteracy.

Arguments for and against this form of provision are reviewed and specific

points taken into account in the analysis. Further the part equally discusses

entrepreneurship in an African context with suggested measures advocated for an

effective developmental move on the continent.

In chapter three, the methodology of the research is discussed

and explanations are given to justify the use of specific techniques. A general

overview of the case study is revisited and attempts of figuring out the

corresponding paths to explore the research question and sub questions through

quantitative and qualitative methods are equally observed. This chapter states

the procedures adopted in gathering the data in Kenya and briefly enumerates

other sources of information related to the topic and establish basis for

analysing these data.

Chapter four on its own gives a presentation and analysis of

the main findings obtained through our research instruments. It addresses the

question `How and why do private school entrepreneurs contribute to

education for all in Kenya?' Particular attention is paid to all the

elements of response given by the respondents and these are critically analysed

in such a way that each sub question is provided with an accurate answer. The

related documentation and pupils' test scores are equally well exploited and

their substance combined with information from other sources. All these are

summarized at the end of the chapter.

Finally, chapter five is concerned with a general conclusion,

suggestions and recommendations for further research. This chapter in a

nutshell relates our study findings to the literature review and provides more

explanations on the research outcomes. In the light of the results, some

suggestions are mentioned and recommendations channelled for future

investigations in the field. This chapter is somehow the «denouement»

of the research.

Chapter Two - Literature

Review

2.1 Introduction

This chapter seeks to highlight the different theories, past

and ongoing research works on the entrepreneurship and educational development

that formed the basis of this study and to discuss related literature on the

variables of this study.

For this purpose, a number of books, articles, journals,

websites and conference reports have been scrutinized in order to provide the

study with consistent and reliable motives for its investigations. A great

importance was given to what many scholars have written or said concerning

education and development in Africa, the Kenyan case included.

This chapter has a focus of three major aspects. The first

part deals with variables on private education in Africa paying attention to

the tremendous development which is being noted in this field over the

continent. The second part will be dealing with questions related to Free

Primary Education (FPE) and private schools for the poor in Africa, followed by

a short look at entrepreneurship in Africa as well as the impact it has on the

development of the continent. Finally the third part shall look at the aspects

surrounding the actions undertaken by private school organisations such as the

Kenyan Independent Schools Association (KISA), a Nairobi based group well known

for their efforts in improving the quality of their schools in Kenya.

The structure outlined for this chapter was deemed well

elaborated and informative enough for a better understanding of our research

topic and the motivation behind the whole study. This will certainly bring more

light to appraise from an African perspective, the role of private school for

the poor in meeting the United Nations Millennium Goals (MDGs) of universal

primary education by 2015. (Tooley and Dixon, 2003)

2.2 Private education in

Africa

The African continent just as others forming the globe has

noted some considerable evolution in the field of education in almost all its

countries. From antiquity to recent times, education was provided and dominated

by private organisations or individuals. (Karmokolias, Y &Maas, 1997)

Diversely organised, the private sector had played over ages

forefront positions in the provision of education be it formal or informal to

the African people ranging from family homes to well established learning

settings, this from indigenous systems to present time. Tracing back the

origins of private schools development in some Eastern African countries,

existing literature reveals the impact role played by the pre-colonial

indigenous systems, the pioneering works of the missionaries and post colonial

periods. (Ssekamwa, J& Lugumba, S, 2002)

Far from the idea of developing a thorough review of the

history of education in Africa, this section will focus on recent and ongoing

studies conducted by a wide range of researchers and scholars related to

private schools for the poor in Africa.

2.2.1 Free Primary Education

and Private school for the poor in Sub Saharan Africa

Primary education in developing countries have for some time

now been at the centre of many agenda in both national and international

meetings in the world. It is believed that the less a population is literate,

the less chances they would have to achieve acceptable development. Under the

powerful supports of international institutions such as the World Bank, UNESCO,

the IMF, bilateral and multilateral cooperation's, many African states agreed

in the early 2000's to render access to primary schooling free of charge.

However, the exploratory assessment report of Free Primary education in

countries such as Kenya identified so many challenges faced by the government

in the preparation and dissemination of this free education. Among these

challenges were recurrent issues ranging from effective communication

strategies from the Ministry of education poor infrastructures, inadequate

comprehensive educational policies, intensified campaigns against HIV/Aids,

financial resources, teachers training and governments concerns with the

promotion of partnership to ensure sustainable implementation of FPE

etc...(UNESCO 2005: 8-11)

Looking closely into one of the most important of the 1948

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, it states that «everyone has a

right to education». Further, in its third paragraph, the above mentioned

declaration concludes that: «parents have the prior right to choose the

kind of education that shall be given to their children» (World education

report 2000:16). This particular aspect of the declaration coupled with the

«illusions» engendered by the FPE initiatives in many African

countries are likely to be the main motivation for pupils massive returns to

private schools.

The idea behind private school for the poor in Africa has been

for some time now highly explored and developed in educational literature of

our days. This recurring notion with which so many scholars and researchers are

now familiar takes its source from a series of studies undertaken and conducted

by some British scholars among which the well known pair Tooley and Dixon. The

results of their longitudinal study carried between April 2003 and June 2005

across India and Africa; reveals a burgeoning activity of private schools

catering for the poor and the poorest especially in the slums and shanty towns

in Makoko, Lagos' state in Nigeria and Ga in Ghana just to name a few across

the continent.

In most cases where they carried out their studies, these

scholars found that in the greatest majority, poor people in the slums and

remote areas in Africa would prefer sending their children in private schools.

In the quest of finding an answer to the trend, several important reasons arose

from parents responses for their choice.

In Lagos state in Nigeria for instance, they found that close

to 70% of schools(355 in number out of total of 540) surrounding the locality

were private and thus having the poor as target population for their provision.

Of these private schools in Lagos state, 233 schools thus 43.1% were

unregistered (Tooley et al 2005:130). This same trend is complemented by other

scholars who have carried out some studies in the same area and they seemed to

agree on one point. In the Lagos state of Nigeria, unapproved schools usually

termed as private do offer schooling opportunities to a good number of children

especially in urban and peri-urban areas. (Adelabu and Rose 2004:2; in Uwakwe

et al, 2008:135)

Investigations of several studies in Sub-Saharan African

countries pinpoint the inadequacy of the public sector (government) to impart

quality education to the overall population (Rose 2002:4-6). In a nutshell,

private schools in Nigeria as well as in many other countries, in the view many

observers play a key role in the provision of education in spite of the fact

that they charge fees and tuitions to the pupils. Even the wage of Free Primary

Education (FPE) which originally was set to provide free and accessible

education especially to the poor in most African states seems not to have had

any major impact on its' development.

In the district of Ga in Ghana where a similar survey on

private school for the poor was carried in the year 2004, still by Tooley and

his team, the number of private schools catering for low income people was out

passing the number of public schools presumably destined to cover the

educational provision in the entire district. Out of the total number of

161,244 reported attending school in the district for the academic year

2003-2004, only a portion of 35.6% were attending government schools while a

good number making up to 64.4% of children were attending private schools(both

registered and unregistered) (Tooley et al 2007:396). These figures are

extremely significant in the perspective of understanding the extent to which

the phenomenon is widely taking leading positions in the field of education. It

would appear that many parents seem to have found in this form of provision,

the best option in the academic achievement of their offspring. Here again the

reasons advanced correlate with most cases in other countries: The government

school system is likely failing in spite of commendable efforts to reclaim its

leadership over such an important sector in the developmental process of each

country. As noted by Tooley et al 2007:409, the private sector is certainly a

significant provider of education in the district of Ga in Ghana.

Cameroon on its own has not been left out of the move. This

country located at the heart of the continent contains a portion of population

of close to 40% living in abject poverty according to official estimates from

the National statistical office (Backiny-Yetna and Wodon 2009:168). Although

the latter in their study assume that «the market share of public

government schools is 86 percent in rural areas and 57 percent in urban

areas» their assertion should however and undoubtedly be subject to field

verification with same surveys method used by Tooley and Dixon. Private schools

do exist in the country and mostly functioning clandestinely and are very often

subject to treats from the ministry in charge urging explicitly the eradication

of «clandestine» private schools. (Yufeh 2007).Nonetheless, one major

trend in this country is the remarkable presence of faith-based providers in

primary (Basic) education sector. However, the perception of the existence of

private schools catering for the poor in Sub-Saharan Africa is often diversely

appreciated. Not all scholars seem to look at this burgeoning sector from the

same perspective. The following paragraph enlightens the critics of the private

school for the poor in Africa.

2.2.2 Critics of private school

for the poor

The idea of private schools offering services of better

quality as compared to that of government schools in Africa has not always been

meet with positive remarks. There have been an emerging range of critics who

actually dispute the role played by the private sector in the process of

fighting illiteracy and imparting Education for All (EFA) all over the

continent. Although from a general point of view some scholar acknowledge the

«appalling standard of provision in public educational systems», they

are however still convinced of the inferior quality of provision delivered in

private schools for the poor. (Watkins 2000: 230-231). To some extent it is

argued that even though the mushrooming of private schools in Africa,

especially with the case of unapproved primary schools in Nigeria stand as an

ultimate response to the government failure in providing appropriate quality

primary education, (Adelabu & Rose 2004:63-64) their expansion should not

however been interpreted as the best option considering the «low

quality» of this provision. (Adelabu & Rose 2004:48)

Among these critics of private schools for the poor in Africa

is one of the most influential by name Keith Lewin, a British professor of

Education at the Sussex University. The latter strongly argues that:

«Primary schooling is a universal right and only

states can make a reality of the delivery rights to populations, especially

those marginalised by poverty» (Lewin 2007:2).

Following his point of view, Lewin assumes that private

providers' actions in the fight against illiteracy in Sub Saharan Africa are

not welcome in the sense that they cannot undertake a responsibility which is

not theirs. The Education for All (EFA) commitments is essentially the

responsibility of states which stand as providers of last resorts, he claims.

(Lewin 2007:2-3)

His arguments go along with what Tooley has termed the

«accepted wisdom» which sees in the private provision a «non

lieu» and rather open more avenues and more privilege for the domination

of states provision supported in this by educational stakeholders, foreign

politicians, Pop stars campaigns and International agencies. In this

perspective the poor and left away children in slums of Africa would have to

wait for actions to be taken in their favour, even if this means waiting for

ever. However, this is turned down for the simple reason that:

«The accepted wisdom, however, is entirely wrong. It

ignores the remarkable reality that the poor in Africa have not have not been

waiting helplessly for the munificence of pop stars and Western politicians to

ensure that their children get a decent education» (Tooley 2006:

9).

In a nutshell, many poor parents of sub Saharan African living

under $2 dollars a day seems to find in private provision, the way forward for

their offspring' future. Somehow betrayed by the government school system,

their children have found refuge in private schools operated by entrepreneurs.

The following part discusses entrepreneurship and development in Africa.

2.3 Entrepreneurship and

development in Africa

Of equal importance as well as the first part of our work in

the whole process of understanding our research, is the idea of

entrepreneurship in an African context. Many attempts have been given to define

Entrepreneurship. However it should be seen in the present context as the

investment will of local businessmen to bring about a difference in the type of

provision that the populations are already used to. Playing strategic roles in

their respective fields, they are said to be at the origin of economic boom in

countries like India and China. Their presence on the continent has always been

felt as the origin of their actions is evolving alongside the various countries

histories. Generally, their impact is usually felt in fields where the

government cannot provide effective service to the entire needy population. As

such they have become a crucial partner in the development process of a nation.

In the perspective of specifying their role, Boettke (2007) states that:

«Where governments cannot address the issues

effectively through the public sector, individuals are effectively operating in

the private sector to define property rights, to innovate with technology, and

to pursue trading opportunities that potentially lift people out of

poverty» (Boettke 2007:3)

According to many economists point of view, Entrepreneurship

should be reconsidered strongly if African leaders want their respective states

to line up with the worldwide development machinery. George Ayitteh, one of the

continent high esteemed development economists for instance argues that fixing

Africa's state equally reposes on private investment. He makes it clear for all

that:

«Private investment is the way out of Africa's

economic miasma and grinding poverty. Africa needs investment in agriculture,

manufacturing, education, health care, telecommunications, and

infrastructure» (Ayittey 2007:158).

Although many would agree that «Entrepreneurship is a

catalyst for economic growth and progress» (Joshua and Russell 2008:247)

it would be worth noting that one of the essential determinant for this

investment which is economic freedom rarely figures on the African investment

agenda. Back to the field of education, it is worth noting the overwhelming

presence of entrepreneurs who out of their personal financial resources set up

and operate schools especially where the demands for education is extremely

high. Rather than waiting for international aid which paradoxically has shown

its limits in the development process of Africa (Easterly 2006), this set of

investors generally closed enough to their communities participate in their own

way to the achievement of one of the MDG's goal: Universal Primary Education.

However their investments and actions are sometimes met with obstacles from the

government in which they act. These obstacles range from restrictions, severe

regulations, non access to big scale loans, licensing procedure etc...All these

factors influence in a long run the possibilities of expanding the investments.

In fact:

«Entrepreneurship operates in an environment greatly

influenced by government policy. In countries where governments are dominant in

every sphere of activity, whether through parastatal enterprises, through

licensing controls, or through obliging farmers to sell at prices set by

statutory marketing boards, the possibilities for gaining entrepreneurial

experience are correspondingly reduced» (Elkan 1988:177)

Such prevailing environment which ironically is very common in

almost all African states, do favour effective investment and thus contribute

to shatter to dream of the majority of African entrepreneurs as they fill

concerned with the development at all levels of their countries and

continent.

Nonetheless, our case study of Kibera in Kenya have given us

the opportunity to ponder a little bit on one association grouping educational

entrepreneurs in that part of the continent. The following part briefly

discusses their actions for the development of education in Kenya.

2.4 The Kenyan Independent

School Association (KISA) and the Development of Private School for the

Poor

One important fact that captured our attention within the

focus of the study was the existence of an association bringing together all

private schools entrepreneurs. The interest in understanding this association

went «crescendo» as we realised that its members were all geared

towards the same objective, which is ensuring a constant quality of private

schools provision in their settings. Set in 1999, the association had ( we

believe they still do) as priority to address the challenges faced by

educational entrepreneurs with the mission to

«empower communities to engage the Government of

Kenya and other stakeholders to pursue policies and actions that promote the

access of all children in informal settlements to a holistic quality

education» (Musani 2008:4)

Faced with all the possible challenges in their respective

communities, the private school owners in Kenya (generally individuals with

previous educational backgrounds) through their association are said to have

been of tremendous support to the poorest and HIV/AIDS orphans. Having as

premium target the poorest population, their schools are certainly not exempted

from recurrent realities of the educational problems in the third world

ranging from the poor infrastructures, teachers turnover to limited resources

just to name a few. However existing literature does point out clearly the

positive role that this association has been playing for the development of

education in Kenya. In fact:

«Over the past ten years, KISA has played an active

role in the independent schools sector promoting education and rights of poor

children»(Musani 2008:2)

It is assumed that if given effective means of functioning,

the services offered to its teachers and members could give more strength and

support to the improvement of the quality of the quality of education in

private schools. Nonetheless even with fewer funds their actions are already

extremely remarkable enough and thus constitute a valuable tool for better days

ahead of private schools in Kenya. An in-depth study of the KISA actions on the

field points out:

«...the independent schools will continue to play a

large role in the education sector in Kenya. By providing low-cost affordable

quality education, low-income families, particularly in the urban slum areas,

will rely on the independent schools for continued quality education of their

children.» (Musani 2008:2)

Such actions undertaken by this group of educational

entrepreneurs in Africa simply correlated with what Tooley (2006) early

mentioned, that is: «The poor have not been waiting helplessly...»

Indeed they have been very active especially concerning the education of their

children. Their actions equally go along with what Barack Obama in his speech

in Accra last July 11th 2009 urged Africans to do in order to foster

development on the continent.

2.5 Summary

This chapter has presented a literature review on Primary

education and entrepreneurship in Africa. Having focused mainly on private

education in that part of the world as well as Free Primary education

initiative, related existing literature published by authors and researchers on

the topics were scrutinized. This has enabled us to establish the theoretical

underpinnings of the research. Firstly, we sought to explain different

variables surrounding education in Africa with particular foci on private

school for the poor on the continent. An appraisal of their dominance over

government schools even despite the Free Primary Education initiative was

elaborated and critics' points of view of this form of provision were equally

visited. As another major focus of our study was about entrepreneurship in

Africa, general aspects of the topics were studied with an emphasis laid on

concerns about its realities. The sections have been structured in such a way

that a thorough understanding of the research analysis will be possible.

Finally, the last section was concerned with the look at a

set of educational entrepreneurs in Kenya and their contributions towards to

betterment of private school provision in Kenya. This section has produced some

facts about the efficacy of such gathering. With the KISA, it is obvious that

the private schools in Kenya will stand as major provider of quality education

in urban slums especially for the poorest, HIV/AIDS orphans and low-income

families.

Chapter Three - Methodology

3.1 The research methods of

the study

3.1.1 Theoretical framework

The methodology chapter reports on the various ways the

research has been carried out and presented. In order to allow an in-depth

analysis of the research questions, a case study was found most appropriate.

The advantage of this specific approach remains the fact that it offers the

researcher the opportunity to probe deeply and analyse interactions between the

factors that explain present status or that influence change or growth and it

therefore provides a ground for one aspect of a problem to be studied in some

depth (Best, J &Kahn 2003:249, Bell 2005:10).

The case study is defined as a research strategy which focuses

on the understanding the dynamics present within single settings and can employ

embedded design or better still multiple level of analysis within a single

study (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 1984).

A number of 20 private school owners (entrepreneurs), 25

teachers and 25 pupils of 5 selected schools were thus chosen to focus the

study on. Researching primary education and entrepreneurship in East Africa

henceforth required specific method that would provide a better understanding

of the complexities surrounding entrepreneurship. From these perspectives, it

then sounded very obvious and relevant to find in the case study approach the

most adequate way of conducting our research considering the socio-economic

environment in which it was done.

However, this structural approach has always met severe

critics from scholars «misunderstandings» of its operational ability

to offer concrete results (Tellis 1997, Yin. Some of the most common points for

these misunderstandings are generally related to the fact that, with this

approach:

Ø The theoretical knowledge is more valuable than

practical knowledge.

Ø One cannot generalise from a single case, therefore,

the single-case study cannot contribute to scientific development.

Ø The case study is most useful for generating

hypotheses, whereas other methods are more suitable for hypothesis testing and

theory building.

Ø The case study contains a bias toward verification,

and

Ø It is often difficult to summarise specific case

studies (Flyvbjerg, 2006:219)

Nonetheless, in a response to a major point of these concerns,

namely that of the generalization in case studies, (Denscombe 1998, cited in

Bell, 2005:11) rightly points out that:

«The extent to which findings from case study can be

generalized to other examples in the class depends on how far the case study

example is similar to others of its type».

Closely related to this last aspect, our conviction still

remained that, the field of education, being very broad and extended in the

overall social sciences, needed some case studies in order to critically

analyse certain phenomenon. The motivation gearing to the massive presence of

private school entrepreneurs and the mushrooming of private schools catering

for the poor in a slum such as Kibera could only be well understood through a

case study approach.

3.1.2 Research method used and

description of data collection

Research in social sciences offers many options concerning the

method to be used by the researcher .These are usually quantitative and

qualitative methods. However, it's very common nowadays for researchers and

scholars and researchers to use both methods depending on their goal target.

It's equally suggested by many scholars that for the case of a «good»

case study, many sources should be used to gather evidence in order to support

or reject the theory. (Yin 1993, 1994 cited in Dixon 2002)

Both quantitative and qualitative methods (equally known as

mixed method or multi-strategy research) were used in the course of this

research, this in a perspective of bringing more accurate information about

the research questions centred on private school entrepreneurship in East

Africa and also to help figure out specific patterns in the various

respondents' answers.

The quantitative approach uses techniques of inquiries

including positive claims and experimental strategy. With this method, the

researcher usually tests a theory by specifying narrow hypothesis and the

collection of data to support or refute the hypothesis. Further, an

experimental design is used in which attitudes are assessed both before and

after the experimental treatment. Finally, the data are collected on an

instrument that measures attitudes, and the information collected is analysed

using statistical procedures and hypothesis testing. (Creswell, 2002:20)

Qualitative method on its own enables the researcher or

inquirer to make knowledge claims based on primarily on constructivism

perspectives. This involves the systematic collection, organization and

interpretation of textual material derived from talk or observation. The

particularity of this approach remains the fact that it is used in the

exploration of meanings of social phenomena as experienced by individual

themselves, in their natural context. (Creswell, 2002:18; Malterud 2001:483)

The research has been carried in Kibera, one of the largest

slums of East Africa. Considering the central question surrounding the study,

it's decided and agreed upon to focus on private school entrepreneurs, teachers

and pupils in selected schools. We deemed necessary to use both methods with

specific task assigned to each method and its instrument. The qualitative

method was used by carrying an in-depth interview with private school

entrepreneurs who operate in the slum of Kibera, while the quantitative method

was used to cover the overall picture of selected schools, carrying out a

census and a survey looking at pupils number, fees, test scores, provision of

certain facilities, all these providing us with scale data. Ordinal data were

also collected by using Likert scales method to measure satisfaction in the

pupil and teachers questionnaires (Best, J &Kahn 2003:318-321).

The collection of information related to this study was made

possible through the following instruments:

· Questionnaires

· Interviews

· Test scores, and

· Documentary

3.1.2.1 Questionnaires

Questionnaires were distributed to a good number of school

entrepreneurs in Kibera, the teachers and pupils in the selected schools. The

structure of the questions was well elaborated based on a «question

type» format (Bell 2005:137-138) so as to enable the researcher to gather

as much accurate information as possible and get to analyze these without any

major problem. They were set in quite simple way taking into account pupil's

level, teachers and entrepreneurs' time constraint. In short, these questions

were detached from all ambiguity and imprecision( Bell 2005:138-139) The

objective of school owners' questionnaires was to find out the motivations

behind their investments in the field of education especially in a slum, about

the facilities offered in the process of their activities.

Teachers and pupils' questions were centred on their level of

satisfaction of the quality of services provided by these entrepreneurs and

what they thought were the shortcomings of these investments.

3.1.2.2 Interviews

Telephone interviews were carried from the EG West Centre

(Newcastle University) with a small number of private schools entrepreneurs as

well as with George Mikwa, the president of the Kenyan Independent School

Association (KISA). This was done following the standardized open-ended

interview type. The wordings and sequence of questions were determined in

advance and all the school owners were asked the same basic questions in the

same order. (Patton, 1990:288-289)

The questions ranged from main concerns on issues surrounding

their motivations from setting private schools in the slum of Kibera, their

point of view concerning the investment climate in the area, the regulatory

environment and finally what they thought was the major gap in their provision.

The latter gave answers to the same questions which were later on compared and

analyzed.

3.1.2.3 Test scores

In order to instigate triangulation, the researcher requested

test scores from school authorities. The objective here was to scrutinize

pupils' achievements in three subjects, respectively: English language,

Mathematics and Kiswahili, the local language.

It was thought earlier that the information contained in the

pupils' test score would enable us to make a correlation between children

personal assessment of their performances in these subjects and what they

actually achieved within the academic year.

However, it's worth noting that these test scores were not

obtained through standardized test, rather they were obtained thanks to the

collaboration of school heads. These test scores provided meaningful

information and its purpose was therefore useful in adding more knowledge to

our field of enquiry (Best, J &Kahn 2003:248)

3.1.2.4 Documentary

Documentary was equally explored as another source of

evidence. The main documentary that provided useful information for the study

was found in presentations delivered at the CATO Institute, Washington D.C by

private school entrepreneurs under the auspice of Professor Tooley and Dr

Dixon. This documentary was accessible through the E.G West website and

discussions were centred on private school entrepreneurship in India, Nigeria,

Ghana and Zimbabwe. In a nutshell, the entrepreneurs in their talks enlightened

the audience on the background information of their business in the field of

education. It was revealed here that most of these entrepreneurs or private

school owners have had a longstanding experience in the educational field prior

to opening their schools.

This «source- oriented» approach has had the merit

of helping us determine our project as well as it did helped us to generate

questions for the research (Bell 2005:123)

Another set of documentary made up of past and ongoing

research on private education were equally explored. Academic articles,

journals and edited books from scholars such as Tooley and Dixon(2005), Rose

and Adelabu(2006), Lewin(2007), Srivastava(2007) just to name a few served as

guidelines in the preparation of the overall research question and thus opened

an avenue for as many sources of investigation as possible.

3.1.3 Target population and

sampling

The population of this study was made up of Entrepreneurs or

school owners, class teachers and pupils. The large number of private schools

in Kibera catering for various social classes prohibited a systematic sample.

In fact random sampling was applied in order select our sample schools and the

respondents. This was conducted in such a way that each has an equal and

independent chance of being selected (Best, J &Kahn 2003:13) Participants

were asked to volunteer for the study and a simple random sample was done.

We were very much interested in private school

entrepreneurship offering services to the poor. As such, twenty school owners

were chosen. Apart from this number, five teachers each and five pupils each

were selected from five different schools. Thus, the total population of 70 was

administered interviews and questionnaires.

3.1.4 Reliability and Validity

of the research

Reliability and validity are considered highly essential in

social science research. They contribute to reassure that the instruments used

in carrying the research were appropriate and effective with close regards to

the central question of the study. We therefore chose to use the above

mentioned instruments in the process of data collection in Kibera with close

regards to these two parameters. In another words, it's advised that a quality

research should produce similar results under constant conditions on all

occasions. Bell (2005:117)

An utmost precaution was taken before the beginning of the

study, which was to see that our instruments fit perfectly well with the

research. We took upon the responsibility to ensure that our instruments of

data collection for entrepreneurs, teachers and pupils were of as high quality

as possible both in terms of design and content, and as unobtrusive and

inoffensive as possible. (Fogelman and Comber, 2007:129)

Another nonetheless major concern was equally that related to

the validity of our research with primary education and entrepreneurship in

Kibera. The more valid a research is, the more credit it gives to the entire

process of measuring various aspects of it content. A critical assessment and

reassessment of the questionnaires and Interviews were done by colleagues and

friends of the EG West Centre under the supervision of Dr Dixon, to help

determine that all the questions measure what they were supposed to measure.

Bell (2005:117)

However, being more complex on its own, measuring the validity

evidence of our research in Kibera required us stress much of certain aspects

of the instruments that were used. This was done with close respect to

emphasise that is usually laid on this issue by scholars when they argue that

validity evidence is based on three broad sources namely: content, relation to

other variables, and construct (Best, J &Kahn 2003:282-286)

While not analysing these three latter parameters of validity

as totally separate entities, we however designed our research in such a manner

to arrive at credible conclusions. (Sapsford and Jupp 1996, cited in Bell 2005:

117-118)

In the perspective of rendering the research more accurate and

realistic, the triangulation of multiple variables of the respondents' answers

were equally done, thus making the overall study reliable and valid.

3.2 Permission and

Ethics

Before engaging ourselves on the field for the research, a

letter of permission for the study and data gathering was sent to the owners of

the selected schools in Kibera. This was done thanks to the collaboration and

support of George Mikwa, the president Kenyan Independent School Association

(KISA). Various principals and school owners received these letters prior to

the investigation. The latter stated in precise words our main objective for

the study, the appropriate schedule as well as the people that we thought could

actively be involved in the process of data collection. . We equally reassured

both the school owners and respondents that the information gathered in this

course shall be treated with strict sense of confidentiality and anonymity,

which are considered the norm for the conduct of research. (BERA 2004, p8)

3.3 Conducting the research

in Kibera

Prior to undertaking this research, a series of reflexion

related to its management and feasibility were conducted with friends and

colleagues. We initially thought of carrying the same research in Cameroon.

Some contacts were already established to serve this purpose. However, due to

time and financial constraints, it was advised by my supervisor that the study

should be carried rather in Kenya. In fact, there was little evidence ahead

that the study, if done in Cameroon would be reliable and valid considering the

fact that we were relying of a journalist in the distribution of the

questionnaires and sending back at Newcastle.

Kenya and Kibera was chosen among other destinations for the

following reasons:

Ø Kibera was known to be one of the largest slums in

East Africa and therefore, there were chances to find private schools catering

for the poor in the locality.

Ø Information at our disposal revealed the existence of

a Union of school entrepreneurs in Kenya, thus offering the opportunity to get

more knowledge on private school entrepreneurs and their functioning body

Ø A good number a research and reports had already been

done on the slum of Kibera and exploring the existing documentation was to be

of great supplement.

Ø Finally, officials of the EG West Centre (Newcastle

University) had very strong ties with entrepreneurs in Kenya and this helped

enormously in the process of data collection.

All the research questionnaires were channelled to George

Mikwa at Nairobi, Kenya and he made sure that these questionnaires reached our

respondents. Upon completing the questionnaires, the same George sent these

back to us at the EG West for evaluation and analysis.

Finally, all the interviews with the president of KISA and

other school owners were carried from the EG West centre with support from my

supervisor and friends.

3.4 Limitation of the

study

No proposed research study is without limitation, this is

simply because due to time constraint and lack of extended financial resources,

it was practically impossible for us to investigate primary education and

Entrepreneurship in all the slums of East Africa. Our study did henceforth

focused on a specific slum, that of Kibera with foci on twenty private school

entrepreneurs, twenty five teachers and twenty five pupils. Though case study

is equally considered flexible, the realities here in these schools would not

necessarily reflect those in some other private schools. This means that our

results cannot to an extent be generalized. The reason for this being that, not

all the teachers and pupils living in and attending private schools in Kibera

did took part in the questionnaire administration. We were aware of the fact

that criticism may arise from population responses as some may consider their

point biased. Further, due to financial constraints, the questionnaires were

elaborated and sent to Kenya through the President of the Kenyan school

Association (KISA) for effective collection of data. This may be considered

another shortcoming of our procedure as it was not done personally by the

researcher. However, specific measures were taken prior to sending the

questions on the field and the analysis equally took note of this aspect.

3.5 Data presentation and

Analysis

Soon after collecting the data in Kibera, they were channelled

to the EG West Centre. The information gathered through interviews and

questionnaire from our sample population was organized, coded, recorded,

edited, analyzed and interpreted to determine the factors surrounding primary

education and Entrepreneurship in East Africa (Bell 2005:203)

The qualitative data contained in questionnaires and

interviews was scrutinized in order to find patterns and similarities within

the data. Thanks to the technical assistance of supervisor and training staff,

it was possible to generate codes to analyze the in depth qualitative data.

The statistical software SPSS served as principal tool of

analyzing and reporting the quantitative results of our findings in a succinct

way (Cramer 2003: 154)

This wonderful software actually enabled us to consider

aspects related to statistical interference and ordinal, nominal and scale

variable. All these were analyzed to allow us to answer questions about the

owners' interests in investment, the regulatory environment and the investment

climate, and the satisfaction level perceived by teachers and pupils (Cramer,

2003: 223)

All data sets were adequately compared in order to determine

the means and the median of our findings in related schools (means, modes and

medians). The central tendency was equally used where appropriate.

The Pearson's correlation was used to determine the

relationship between teachers and pupils' level of satisfaction in the selected

schools and their degree of involvement in academics. An interpretative

approach of statistical difference was equally carried to figure out the

sampling error in the control group, especially with pupils test scores (Best,

J &Kahn 2003:393-395)

This correlation analysis has helped to discover the

relationship between the investments in any kind in the entrepreneurs' schools

and the pupils' achievements. With this, we were able to say if their actions

were having either a positive or a negative impact. (Myers & Well,

2003:46)

From this information, a detailed analysis was done with

specific regards to our study's central questions and sub questions.

3.6 Conclusion

In this chapter, we have given a thorough picture of our

research method including process of collecting our data in Kibera. Case study

was found appropriate and steps governing such an approach have been well

followed. Hence, a multi strategy source plan was adopted for this purpose.

Questionnaires, interviews, documentary etc were used to access related

information on primary education and Entrepreneurship in one of the largest

slums of East Africa.

All the 20 Entrepreneurs, 25teachers and 25pupils' kindly

responded to our study. Together with information gathered through past and

ongoing research papers, a detailed report of the analysis of their answers has

been provided. It has been assumed that all these data from various sources

will likely provide concrete and reliable results of the study. Specific

parameters such as ethical issues, limitation of the study as well as data

presentation and analysis were equally addressed in this chapter.

The following chapter presents our results. Subsequently a

further step from there is taken to draw a series of conclusions.

Chapter Four - Analysis

4.1 Introduction

This chapter sets out the analysis of the data collected in

the slum of Kibera during May 2009 in order to attempt to answer the overall

question of this thesis which is:

`How and why do private school entrepreneurs contribute to

education for all in Kenya?'

This chapter will be divided up into five main parts starting

with a section to set the scene concerning private schools for the poor in

Kibera. These will provide analysis of the data to answer the overall thesis

question through the following sub questions:

· What are the entrepreneurs' major motivations for

investment in the field of education?

· Have these schools suffered from the government's

introduction of 'Free Primary Education (2003)' in terms of enrolment?

· What is the satisfaction level from their

investment as perceived by pupils and teachers?

· What factors could be identified as the major gaps

in this type of provision?

The final question acts as a conclusion to this chapter. The

next section provides background to the schools and the pupils and teachers who

participate within them.

4.2 Background

This research was carried out in 20 private schools in the

slum of Kibera, the largest slum in East Africa. Data were gathered via

questionnaires from 20 school owners, 25 student and 25 teachers from five

schools. Interviews were carried out with George Mikwa, the president of the

Kenya Independent School Association (KISA) as well as four school owners and

directors. The following background information will be necessary in

understanding the results of the findings and being able to put these in

context.

4.2.1 School and school owners

There are roughly 116 private schools currently operating

within the slum area of Kibera (Dixon, 2009). Data were gathered in 20 of these

schools. The schools operate their own Association, which is the Kenyan

Independent Schools Association (KISA), an association that was set up and

registered in 1999 with the Kenyan Government. The association draws its

membership specifically from non formal schools (Private). In tracing back the

origins of this association, its current president George Mikwa (a private

school entrepreneur himself) recounts that:

«The idea of KISA was to have an umbrella body that