|

CIPSEM - Centre for International Postgraduate Studies in

Environmental Management

40th INTERNATIONAL POSTGRADUATE COURSE ON

ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT FOR DEVELOPING AND EMERGING COUNTRIES

FINAL PAPER

TITLE: ADDRESSING CLIMATE CHANGE THROUGH

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT TOOLS IN PLANNING PROCESSES:

INTERNATIONAL PRACTICES AND PERSPECTIVES FOR NIGER

AUTHOR: MR. MOUSSA LAMINE

COUNTRY: NIGER

SUPERVISOR: PROF. DR. JOCHEN SCHANZE

DATE: JULY 2017

ABSTRACT

The occurrence of global climate change (CC) particularly in

developing countries is fully confirmed by the Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) of

the Intergovernmental Panel on CC (IPCC) published in 2013/2014 and human

activities are the main causes of observed changes in climate today. The nature

and type of development that occurs, has implications on greenhouse gas (GHG)

emissions as well as the vulnerability of society to CC impacts. Therefore, it

has been widely recognised that there is a need to integrate consideration of

CC and its impacts in development policies, plans and programmes (PPP).

Nowadays, many countries have developed legislations on environmental

assessments tools mainly Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and Strategic

Environmental Assessment (SEA) which integrate CC in the assessment of PPP.

This paper assesses first the integration of CC in the European Union Directive

on EIA, the European Union Directive on SEA and the Niger's Legislation on EIA

and second compares the EIA procedure in European Union and in Niger. The

latter considers as main criteria the integration of CC in five key steps of an

EIA procedure. A literature review on the relationships between CC and the

environmental assessment tools, including the relevance of the integration of

CC in EIA and SEA and how this topic is currently addressed worldwide is

carried out. The study reveals that Niger Legislation on EIA does not provide

any requirement regarding CC mainstreaming in EIA process in the five steps

considered for the comparison while the EU Directive on EIA requires

consideration of CC in the three steps even though it does not provide any

specific requirement regarding CC in the project appraisal and the project

monitoring steps.

Keys words: climate change,

environmental assessment, European Union, Niger.

II

LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES

Figure 1: Guidance on Incorporating CC considerations in EIA

8

Figure 2: Modifications of the Environmental Assessment

Procedure to Address CC Adaptation

Considerations 10

Figure 3: Administrative Procedure of Environmental Impact

Assessment in Niger 14

Figure 4: The EU EIA Procedure According to Directive 2014/52

19

Table 1: Comparison of EU EIA Directive and Niger Ordinance

97-001 on EIA and its Decree 2000-397 on

Administrative Procedure 23

Table 2: Actions to be carried out for the Implementation of

the Recommendations 28

III

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This final paper would not have been possible without the help

of many institutions and people whom I would like to thank warmly. The honor

comes first to UNEP/UNESCO/BMU for giving me an opportunity to be part of the

40th International Postgraduate Course on Environmental Management for

Developing and Emerging Countries.

I would like also to thank the dynamic CIPSEM staff for their

assistance, availability and efforts made to achieve the educational objectives

of our training course.

I express my profound gratitude to my supervisor, Professor

Dr. Jochen Schanze for having accepted and supervised me and also directed the

conduct of this work.

Thanks to all my lecturers from various institutions in

Dresden and abroad who inspired me with their many lectures and excursions and

to all the institutions that accepted us in their premises for excursions.

I would like to thank my home organisation, the General

Directorate of Environment and Sustainable Development of Niger for allowing me

to attend this course and my family for its patience during my stay in

Dresden.

Finally, thanks to all my fellow course participants for their

openness and brotherhood/sisterhood spirit and moral support.

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT i

LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES ii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS iv

LIST OF ACRONYMS vi

1. INTRODUCTION 1

1.1. Background 1

1.2. Problem Statement 2

1.3. Objectives 3

1.4. Approach 3

2. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CLIMATE CHANGE AND ENVIRONMENTAL

ASSESSMENT TOOLS IN

PLANNING PROCESSES 5

2.1. Description of Relevant Concepts 5

2.1.1. Climate Change 5

2.1.2. Environmental Assessment 5

2.1.3. Public Participation/ Public Involvement 6

2.2. Relevance of Mainstreaming Climate Change in Environmental

Assessment Procedures 6

2.2.1. Climate Change in Strategic Environmental Assessment 6

2.2.2. Climate Change in Environmental Impact Assessment 7

3. INTEGRATION OF CIMATE CHANGE ISSUES IN ENVIRONMENTAL

ASSESSMENTS TOOLS IN

NIGER AND EUROPEAN UNION COUNTRIES 11

3.1. Assessment of Niger Legislation on Environment Impact

Assessment 11

3.1.1. History of Environmental Assessment (EA) Procedure in

Niger 11

3.1.2. EIA Procedure in Niger 11

3.1.2.1. Project Notification 11

3.1.2.2. Screening 12

3.1.2.3. Scoping 12

3.1.2.4. Realisation of the EIA 12

3.1.2.5. Review of Impact Assessment Report 12

3.1.2.5.1. Internal Review 12

3.1.2.5.2. External Review 13

3.1.2.6. Authorisation of Project 13

3.1.2.7. Monitoring Conditions 13

3.1.3. Public Participation 15

3.1.4. Climate Change in Niger EIA legislation 15

3.1.5. EIA Procedure Limits 15

3.1.5.1. Inadequate Public Participation 15

3.1.5.2. Environmental Monitoring Missions Funded by the Project

Developer 15

3.1.5.3. Ambiguity Related to the Scope of the EIA as a Tool

15

3.1.5.4. Failure to Categorise Projects Subjugated to EIA 16

3.2. Assessment of the European Union Directive on Environmental

Impact Assessment 16

3.2.1. Presentation of the Environmental Impact Assessment

Procedure in EU 16

3.2.2. EU Environmental Impact Assessment Procedure 16

3.2.2.1. Screening 17

3.2.2.2. Scoping 17

3.2.2.3. Realisation of the EIA 17

3.2.2.4. Assessment and Evaluation of the EIA 17

3.2.2.5. Project Appraisal 18

3.2.2.6. Determination of Monitoring Conditions 18

3.2.3. Public Participation in EU EIA Procedure 20

3.2.4. Climate Change in EU Directive on EIA 20

3.3. Assessment of the European Union Directive on Strategic

Environmental Assessment 21

3.3.1. Limits of the EU SEA Directive 21

4. COMPARISON OF ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT PROCEDURE IN

EUROPEAN UNION

(EU) AND NIGER 22

4.1. Criteria for Comparison 22

4.2. Results 22

4.3. Discussions 24

5. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 24

ACTION PLAN FOR THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE RECOMMENDATIONS 26

References: 29

LIST OF ACRONYMS

BEEIA: Bureau of Environmental Evaluation and

Impact Assessment

CA: Competent Authority

CARICOM: Caribbean Community

CC: Climate Change

CNEDD: Conseil National de l'Environnement

pour un Développement Durable

COP: Conferences of Parties

DAC: Development Assistance Committee

EIA: Environmental Impact Assessment

ESMP: Environmental and Social Management

Plan

EU: European Union

GDP: Gross Domestic Product

GHG: Greenhouse Gas

IFAD: International Fund for Agricultural

Development

INS: Institut National de la Statistique

IPCC: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate

Change

MESU/DD: Ministère de l'Environnement,

de la Salubrité Urbaine et du Développement Durable

NEPA: National Environmental Policy Act

OECD: Organisation for Economic Co-operation

and Development

PPP: Policies, Plans and Programmes

SEA: Strategic Environmental Assessment

ToR: Terms of References

UNCEA: Commission Economique des Nations

Unies pour l'Afrique

UNFCCC: United Nations Framework Convention

on Climate Change UNDP: United Nations Development

Programme

WB: World Bank

1

1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. Background

Climate change (CC) is a main concern worldwide at the level

of governments, communities, and businesses due to rising understanding of

possible CC impacts on trade, security, ecosystems, and the well-being of

humans and other species. In addition, the occurrence of global CC particularly

in developing countries is fully confirmed by the Fifth Assessment Report (AR5)

of the Intergovernmental Panel on CC (IPCC) published in 2013/2014 and human

activities are the main causes of observed changes in climate today (Ogbonna

and Albrecht, 2015). Such anthropogenic influences that contribute to CC

include the burning of fossil fuels, the combustion of biomass, agriculture,

and deforestation. Globally, awareness of CC and impact and risk research have

increased in recent times. As a result, there are several actions from many

stakeholders in the public and private sectors especially at the national and

local levels that focus on understanding the challenges that besiege CC issues

and reducing the associated effects (Hallegatte et al., 2011).

CC also poses a serious challenge to economic development. The

nature and type of development that occurs has also implications for greenhouse

gas (GHG) emissions as well as the vulnerability of society to CC impacts.

Therefore, it has been widely recognised that there is a need to integrate

consideration of CC and its impacts in development policies and projects

(Agrawala et al., 2010).

In Niger, the issues of the environment are governed by many

legal documents such as the Constitution of November 29th, 2010 and the Law

98-56 of December 29th, 1998 that outline the role that government and

non-government institutions should play in the environmental management. Niger

has also signed numerous international environmental agreements. In response to

the adverse effects of CC, Niger signed and ratified the United Nations

Framework Convention on CC (UNFCCC) on June 11th, 1992 and July 25th, 1995 and

the Kyoto Protocol on December 1996 and March, 2004 (MESU/DD, 2015)

respectively and signed the Paris Agreement on CC in 2016.

For the implementation of the UNFCCC, Niger created the

National Council of Environment for Sustainable Development (CNEDD in French)

in 1996 to coordinate and monitor the national policy of environment and

sustainable development. The CNEDD has prepared the first and the second

national communications to the Conferences of Parties (COP) respectively in

2000 and 2009 and elaborated the National Action Programme for Adaptation to CC

in 2005 to reduce harmful effects of CC in line with the UNFCCC requirements

(UNDP, 2013).

2

In addition, since 2011, the integration of CC becomes a

requirement in planning processes as stated by the Decree 2011-057 of January

2011 (article 3)1: `'the CNEDD should ensure that CC and adaptation

dimensions are integrated in the development policies, strategies and

programmes».

1.2. Problem Statement

Niger, country located in the sub-Saharian zone of Africa has

suffered for several decades the detrimental effects of CC with irregular

precipitations badly distributed in space and time. The climate is arid to the

north, Sahelian (300-600 mm) to the west, to the south-central and to the east

and Sahelo-Sudanian (> 600 mm) in the extreme south-west. Only 1% of the

territory (extreme southwest) receives more than 600 mm of rain per year, while

89% of the territory, located in the northern part, receives less than 350 mm

of rain per year (IFAD, 2013). The spatial, annual and inter-annual variability

of these precipitations expose populations to deficits in frequent

agro-pastoral production. As a matter of fact, its Sahelian climate is

reflected in recurrent dry years that have become more frequent since 1968

(CNEDD, 2006). This situation is linked to the nature of Niger's climate and to

CCs whose manifestations through the adverse effects of extreme weather events

constitute a major handicap for the development of the country. Recurrent

droughts cause negative impacts on the natural environment, such as the loss of

forest resources, loss of biodiversity, land degradation and depletion of water

resources. By undermining ecosystems, CC compromises food production in general

and increases the rivalries and tensions between human communities for access

to natural resources.

With a population estimated at 17,807,117 inhabitants in 2013

(INS-Niger, 2014), Niger has a low-diversified economy characterised by a high

dependence on the primary sector (agriculture and livestock). By assessing the

structure of Niger`s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2014, it is clear that the

primary sector is predominant and contributes to 35.5% followed by the tertiary

sector (38.6%) compared with only 18.9% for the secondary sector dominated by

the exploitation of Uranium (UNCEA, 2015).

That is why Niger now focuses on industrial development

through the extractive and agro-food industries which can be a pillar for the

national economy and contribute to strengthening the country's economic

development. In addition, the contribution of the industrial sector to the

formation of GDP has remained negligible with fewer companies in the mining

sector (Uranium, Coal and Gold).

However, industrial units are considered to be polluting

enterprises because they are responsible for the emission of considerable

quantities of pollutants, the effects of which are detrimental to the human

health and the biophysical environment. Therefore, the integration of the

concept of sustainable development into the planning systems for the

implementation of major industrial projects becomes essential to meet society's

growing concerns about economic, social and environmental issues.

In order to deal with this situation, Niger has put in place a

legal framework for environmental protection, in particular that related to

environmental and social assessments, in accordance with international

1 Decree 2011-057/PCSRD/PM of January 27th, 2011 that modifies

and completes the Decree 2000-072/PRN/PM of August 04th, 2000 concerning the

creation, assigning and composition of CNEDD.

3

commitments on environment. However, the legal texts governing

environmental and social assessments in Niger have been adopted almost 19 years

ago2 and present enormous inadequacies in the sense that they do not

take into account the CC dimension in the development and implementation of

national or/and sectorial policies, plans and programmes.

It is therefore imperative to rethink the mechanisms of

dealing with global environmental problems, in particular, CC through updating

the legislative environmental framework and appropriate ways of planning, but

also by strengthening the environmental assessment for the implementation of

policies, plans and programmes with a view on synergy of action, taking into

account the views of stakeholders (public participation) and response to

current demands.

1.3. Objectives

The overall objective of this study is to assess the

integration of CC mitigation and adaptation in the environmental assessment

procedure in Niger and European Union.

Specifically, the study aims to:

y' Analyse the relationships between CC and

environmental assessments tools;

y' Analyse the integration of CC issues in

environmental assessment tools in Niger and European

Union ;

y' Compare the Environment Impact Assessment

procedure in European Union (EU) and Niger;

y' Propose recommendations to the Ministry of

Environment and Sustainable Development of Niger.

1.4. Approach

In order to achieve the above objectives, the following approach

is used:

y' A literature review about CC, the

environmental assessment tools and the relationships between them. This

includes the relevance of the integration of CC in Environmental Impact

Assessments (EIA) and Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) and how this

topic is currently addressed worldwide. The views of researchers and that of

international and national credible institutions from books, articles and

internet is used as research sources;

y' An analysis of the current situation in

terms of integration of CC issues in environmental assessment guidelines and

directives taking the examples of the European Union EIA Directive, the

European Union SEA Directive and the Niger Ordinance on Institutionalisation of

EIA is considered;

2 Refers to the Framework Law on Environmental Management No.

98-56 of December 29th, 1998 and Ordinance No. 97-001 of January 10th, 1997 on

Institutionalization of Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA).

4

y' A comparison of the European Union EIA Directive and the

Niger legislation on EIA is based on the review of literature on theory and

concept of mainstreaming CC in Environmental Impact Assessment.

y' An analysis of the EU SEA directive to get inputs for a new

bill on SEA to Niger that does not have any legislation regarding that

environmental assessment tool;

y' From the analysis and the comparison derived

recommendations for the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development of

Niger to integrate CC dimensions in environmental assessment tools.

The following documents are used to carry out the analysis and

the comparison of environmental assessment tools:

y' Niger Ordinance 97-001 on Institutionalisation of

Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) of January 10th, 1997;

y' Decree N°2000-397/PRN/ME/LCD of 20th October 2000 on

EIA administrative procedure in Niger y' Directive 2001/42/EC of the European

Parliament and of the Council of 27 June 2001 on the assessment of certain

plans and programs on the Environment;

y' Directive 2014/52/EU of the European Parliament and of the

Council of 16 April 2014 amending Directive 2011/92/EU on the assessment of the

effects of certain public and private projects on the environment.

5

2. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CLIMATE CHANGE AND ENVIRONMENTAL

ASSESSMENT TOOLS IN PLANNING PROCESSES

2.1. Description of Relevant Concepts 2.1.1. Climate

Change

Climate Change is defined by the United Nations Framework

Convention on CC (UNFCCC, 1992, article 1)3 as `'a change of climate

which is attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the

composition of the global atmosphere and which is in addition to natural

climate variability observed over comparable time periods». In this

definition, the UNFCCC makes a distinction between CC attributable to human

activities altering the atmospheric composition and climate variability

attributable to natural causes.

2.1.2. Environmental Assessment

The concept of environmental assessment derived its origin

from the United States National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) but it

has been considered, some years ago, to have the same meaning as an

Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). As a matter of fact, many countries have

been implementing EIA and an equivalent or comparable process in those

countries is called environmental assessment (Parent, 2002; cited in

Cissé, 2013).

Sadler (1996, p.15) defined environmental assessment as

?a systematic process that consists of assessing and documenting the

opportunities, capabilities and functions of natural resources and systems, in

order to facilitate sustainable development planning and decision-making in

general and to anticipate and manage the negative impacts and the consequences

of development adjustments in particular?. This definition, though

seems to be broad contains some key terms such as `'assessing»,

`'anticipate» or `'negative impacts» and specifies the objective of

environmental assessment. Cherp (2001) defined environmental assessment as

?a formalised, systematic and comprehensive process for identifying,

analysing, and evaluating environmental consequences of a proposed action,

consulting the views of the affected parties, and taking the findings of this

evaluation and consultation into account in planning, authorising, and

implementing this action.? While the first definition leant on

process and impacts, the former one includes the issues of public involvement.

Depending on the level of application, environment assessment can be considered

a synonymous of Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) or Strategic

Environmental Assessment (SEA).

Environmental Impact Assessment

As mentioned above, the environmental impact assessment (EIA)

has been considered as the same as the environmental assessment deriving from

the same origin that is, the U.S. National Environmental Policy Act of 1969

(NEPA). Since then, many countries have been using it as tool in development

projects planning

3

https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/conveng.pdf.

6

process even though the approach differs from one country to

another. The International Association for Impact Assessment (IAIA,2009)

defines EIA as `'the process of identifying, predicting, evaluating and

mitigation the biophysical, social and other relevant effects of proposed

development proposals prior to major decisions being taken and commitments

made».

Strategic Environmental Assessment

The term `strategic environmental assessment' was coined in

1989 (Thomas et al., 2002) and an understanding of the concept was derived from

that of project-based environmental impact assessment (EIA) and the principles

of SEA and EIA were perceived to be the same. As stated by Dalal-Clayton and

Sadler (1999, p.1), an internationally agreed definition of SEA does not exist,

but the interpretation offered by Sadler and Verheem (1996) is among those

which are widely quoted: "SEA is a systematic process for evaluating the

environmental consequences of proposed PPP initiatives in order to ensure they

are fully included and appropriately addressed at the earliest appropriate

stage of decision-making on par with economic and social considerations».

Moreover, SEA is often considered as a complement to project-based

Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) so that environmental assessments are

conducted at all levels of decision-making; from PPP formulation to project

management and implementation (Chaker, et al., 2005).

2.1.3. Public Participation/ Public Involvement

As public participation or public involvement is one of the

most important aspects in planning processes, a clear understanding of the

concept is supposed to allow an effective evaluation of the procedure of the

environmental assessments tools (SEA and EIA). André, et al. (2006)

defined public participation as `' the involvement of individuals and groups

that are positively or negatively affected by, or that are interested in, a

proposed project, program, plan or policy that is subject to a decision-making

process». This definition highlights the involvement of all stakeholders

whether they are positively or negatively impacted by the planning process in

the management of their resources and the definition of strategies for a better

future of their living area. In addition, public participation is one of some

important elements of Principle 10 of the 1992 Rio Declaration regarding the

right of the public to access environmental information, decision-making and to

judicial and administrative proceedings4.

2.2. Relevance of Mainstreaming Climate Change in

Environmental Assessment Procedures

2.2.1. Climate Change in Strategic Environmental

Assessment

Climate Change can be seen as a typical cumulative

environmental effect resulting from many individual factors for which

appropriate answers must be found. SEA is needed to provide a framework for

evaluating and managing a wide range of environmental dangers and contribute to

the incorporation (or «mainstreaming») of CC considerations into PPP.

Nevertheless, the empirical evidence and experience on

4

http://www.unep.org/Documents.Multilingual/Default.asp?DocumentID=78&ArticleID=1163&l=en

7

the area of CC mitigation and adaptation concerns in PPP

through SEA is not well developed (Suzaul-Islam and Yanrong, 2016). The

questions that have to be asked in this context are: which roles can SEA play

regarding to CC? How far can SEA contribute to the mitigation of negative

effects of CC? How the impacts of the PPP on CC and the CC induced impacts on

the PPP themselves should be considered?

From the questions raised above, it is clear that the

mainstreaming of CC into SEA faces many challenges. One that has to be

mentioned is that dealing with the effects of CC in SEA throws up the question

as well about how risks can be dealt with that are brought about by CC because

the effects of CC do not only have destructive extents that are difficult to

predict, but they also occur with a probability that is very difficult to

determine and affect societies or social groups with differing vulnerability or

resilience (Weiland, 2010). For example, as noted by Lee and Walsh(1992 cited

in Larsen et al. 2013) in the early stages of SEA, the most likely significant

challenges faced when developing and implementing SEA are how ensuring that

uncertainty is satisfactorily handled at each step of the assessment

procedure.

Other challenges are those regarding the mainstreaming of some

issues such as the gender in the context of adaptation responses, the way the

indigenous people will be affected by CC and the multi-sectoral coordination of

the process in all stages of an SEA procedure (OECD/DAC, 2010).

Finally, the assessment of CC impacts for human activities

such as agricultural sector that contributes to a significant share of the

greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, 17% directly through agricultural activities

and an additional 7% to 14% through changes in land use(OECD,2015) is another

issues that has to be handled while considering CC in SEA.

2.2.2. Climate Change in Environmental Impact

Assessment

Mainstreaming CC into national policies, plans, and

development projects is a very important way to reduce vulnerability to climate

impacts and variability, increase the adaptive capacity of communities and

national activities facing climate impacts, and to ensure sustainable

development (UNDP, 2012). One of the most compelling reasons to integrate CC in

EIA is that every project is designed with some assumption about the climate in

which it will function and the design criteria must be based on probable future

climate that is CC over the life of the project. For example, most of the huge

projects like buildings, highways, harbor facilities, mining, etc. have

relatively long life time of decades and partly even hundreds of years and for

such kinds of projects the EIA is required. Thus, it is important to take into

account the influence of CC on the project and how the project will affect the

surrounding environment under future conditions while undertaking EIA of

projects. Effective integration of CC considerations requires that

project-relevant short-medium and longterm CC impacts are identified using

appropriate climate projection models and CC `'scenarios» (CARICOM et al.,

2004).

Another reason for mainstreaming CC in EIA procedure is that

it constitutes a useful mechanism to implement substantive provisions of

legally binding international environmental agreements as EIA is accepted as a

universal approach to inform and influence decision-making on crucial

socio-environmental matters among which climate change plays a paramount role

(Sánchez and Croal 2012). Besides, the

8

mainstreaming CC in EIA is one of the commitments of the

Parties at the UNFCCC whereby they are invited to undertake measures to

mitigate or adapt CC in PPP implementation,' (Article 4.1f)5.

As stated by Agrawala et al., (2010), despite the tremendous

need of mainstreaming CC in EIA, few countries notably Australia, Canada,

Guyana, Jamaica, Kiribati, the Netherlands, Trinidad and Tobago, have actually

moved towards operational guidelines and/or adjustment of regulatory frameworks

to incorporate adaptation to CC within EIA procedures. Among them, Canada and

the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) have established detailed operational

guidance on incorporating consideration of CC impacts and adaptation within EIA

procedures. For example the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency (CEEA)

provides general guidance to incorporate adaptation and mitigation to CC.

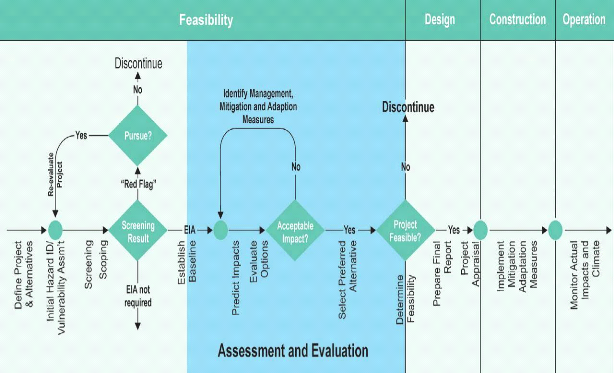

Figure 1 below summarises the recommended procedures for addressing CC impacts

developed by the CEAA. Each of the steps proposed can mark entry points in the

generic steps of a traditional EIA procedure.

Figure 1: Guidance on Incorporating CC considerations in

EIA

|

Step 1-Preliminary Scope for Impacts Assessments

Considerations

|

· Focus on general considerations and readily accessible

information;

· Are they likely impacts considerations associated with

the project that should be addressed in greater detail;

· Document a rationale as to why or why not;

· If there are no likely impacts considerations that

should be addressed in greater detail, no further analysis is required;

· Proceed to Step 2 if further analysis is required;

|

Step 2- Identify impacts considerations

|

· Identify project sensitivity to possible changing

climatic parameters ;

· Conduct more detailed collection of regional CC and

project specific information;

· Clarify changing climatic parameters (magnitude,

distribution and rate of changes);

|

Step3-Assess impacts Considerations

|

· Assess range of possible changes to climatic

parameters;

· Determine the range and extent of possible impacts on the

project;

· Assess the potential risks to the public or

environment

· Based upon the risks to the public or environment

resulting from the effects of climate on the project, determine whether impact

management is required;

· If no further action is required, document impact

analysis. No impact management required;

· Proceed to step 4 if further action is required;

|

Step 4-Impacts Management Plans

|

If the project is likely to pose risks to the public or

environment resulting from the effects of CC:

· Clarify mitigation measures to reduce project

vulnerability;

· Clarify adaptive management plan to reduce risks

associated with CC;

· Incorporate ongoing information gathering and risk

assessment;

· Distinguish between public and private sector risks and

responsibilities

|

Step 5- Monitoring, follow up and Adaptive

Management

|

|

5

https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/conveng.pdf.

If the project is likely to pose risks to the public or

environment resulting from the effects of CC:

· Monitor status of project and effectiveness of

mitigation measures;

· Implement remedial action as necessary;

· Incorporate `' lessons learned' 'into normal

procedures

· Address evolving project and CC knowledge, technology,

policy and legislation.

|

9

Source: Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency (2003).

In addition, the integration of CC adaptation considerations

should be undertaken within the existing environmental impact assessment

framework, with little modification to existing procedures (CARICOM et al.,

2004). Less modification required to existing environmental impact assessment

procedures to address CC adaptation considerations are given in the figure 2

below.

Regarding the CC mitigation of projects impacts, it is difficult

to determine with certainty that a given source of GHG has a measurable

cause-and-effect relationship on local, regional, or global climate. As such,

the incremental contribution of a project to national or global GHG emissions

cannot be linked to specific changes in global climate (Ohsawa and Duinker,

2014).

10

Figure 2: Modifications of the Environmental Assessment

Procedure to Address CC Adaptation Considerations

Source: CARRICOM et al., 2004

11

3. INTEGRATION OF CIMATE CHANGE ISSUES IN ENVIRONMENTAL

ASSESSMENTS TOOLS IN NIGER AND EUROPEAN UNION COUNTRIES

3.1. Assessment of Niger Legislation on Environment

Impact Assessment 3.1.1. History of Environmental Assessment (EA) Procedure in

Niger

Niger officially entered into the EA procedure in 1997 with

the adoption of the Ordinance 97-001 of January 10th, 1997 on the

institutionalisation of EIAs. Article 4 of the Ordinance requires that

development activities, projects or programs that may affect the natural and

human environment, because of their size or their impact are subject to the

prior authorisation of the minister in charge of environment. The authorisation

is granted on the basis of an environmental impact assessment prepared by the

developer.

The operationalisation of EIAs in Niger began in 1998 with the

creation of the Bureau of Environmental Evaluation and Impact Assessment

(BEEIA) and the three implementing decrees of the ordinance adopted in 2000.

The implementing decrees are:

y' Decree 2000-369 / PRN / ME / LCD of 12 October

20006 on the responsibilities, organization and functioning of the

BEEIA;

y' Decree 2000-397 / PRN / ME / LCD of 20 October 2000 on the

administrative procedure of Environmental Impacts Assessment;

y' Decree 2000-398 / PRN / ME / LCD of 20 October 2000

determining the list of activities, works and planning documents for which

environmental impact assessments are required.

As far as the Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is

concerned, it is important to stress that there are no specific guidelines in

Niger. In practice, SEA is conducted in the same way as EIA or sometimes in

accordance with the funding institutions requirements like World Bank. That

represents a huge gap and deficiency in the strategic planning of PPP.

3.1.2. EIA Procedure in Niger

The Decree 2000-397 sets out the administrative proceeding to

be followed in assessing and examining the environmental impacts of a project

and specifies the content of the EIA report and the public consultation

mechanism. The stages of the proceeding shall include project notification,

screening, scoping, realisation of the EIA, review of EIA report, authorisation

of project and monitoring conditions (Art. 4). In addition, Article 7 of the

decree defines the content of an EIA report.

3.1.2.1. Project Notification

6 The decree 2000-369 has been amended several times.

12

The project Notification is a brief description of the

project, its location, potential positive and negative environmental impacts

which it is likely to generate and the schedule for its completion. It is

submitted to the ministry of environment by the developer. It must be

accompanied by maps, plans, sketches and other relevant documents helping to

situate the project in its context.

3.1.2.2. Screening

The screening allows determining if an EIA is required. It is

conducted by the BEEIA, within a period of ten days from the date of receipt of

the notification to give the minister of environment its opinion. The minister

shall notify the developer within 48 hours from the date of receipt of the

BEEIA opinion. At the end of this period, the developer may consider his

project notification as agreed.

3.1.2.3. Scoping

During this phase, the terms of reference (ToR) are elaborated

by the project developer in collaboration with the BEEIA in case an EIA is

deemed necessary. The ToR identifies the important environmental issues

including concerned populations opinion and guide the EIA so that

investigations and resources are focused on those aspects of the project that

are likely to produce significant adverse impacts. They are submitted by the

project developer to the ministry of the environment via BEEIA for approval.

3.1.2.4. Realisation of the EIA

This step is under the responsibility of the developer and is

conducted according to the (ToR). The developer conducts the inventory leading

to the description of the initial state of the biophysical and human

environment; identifies and assesses the impacts, carries out the choice and

analyses the alternatives, proposes mitigation and improvement measures,

develops an Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) that defines the

monitoring conditions and elaborates the EIA report.

3.1.2.5. Review of Impact Assessment Report

The draft EIA report is submitted for a review to the BEEIA,

which has twenty-one days to review the EIA report and submits its results to

the minister of the environment. There are two types of reviews:

3.1.2.5.1. Internal Review

It aims to ensure that the content of the draft report

complies with the requirements of the ToR and that of Article 7 of the Decree

2000-397 on the content of an EIAR. It is conducted by the BEEIA which

transmits an admissibility notification of the report to the developer.

13

3.1.2.5.2. External Review

Two main activities are carried out for the purpose of the

external review.

y' The BEEIA conducts a field verification mission to compare

the information contained in the draft EIAR and the reality on the ground and

organises a public hearing to take better into account social concerns. This

activity leads to the elaboration of a field and public consultation report.

y' In the meantime, an ad-hoc committee composed of the

project' stakeholders is set up by the minister of environment via BEEIA to

examine the quality of the EIA report at a workshop to be organised for that

purpose. The field and public consultation report elaborated by the BEEIA is

also presented during the workshop.

3.1.2.6. Authorisation of Project

At the end of the workshop, the BEEIA reports the results of

the EIA procedure to the minister of environment within seven days from the

date of receipt of the ad-hoc committee's meeting report. The final decision is

supported by the field and public consultation and the ad-hoc committee meeting

report. On the basis of these reports, the decision will either be an

authorization (issuance of the Certificate of Environmental Compliance) for the

implementation of the project or a rejection of the EIAR, hence its resumption

with new ToR.

3.1.2.7. Monitoring Conditions

Monitoring conditions are the responsibility of the developer,

the CA and the BEEIA. Prior to the implementation of the project, the CA

identifies the impacts that need to be monitored as well as the relevant

indicators. It will also specify the schedules for monitoring and evaluation,

people responsible for follow up and the measures to be taken in case negative

impacts would exceed expectations. As a result, the project developer submits

to the BEEIA the ESMP that allows the elaboration of the environmental

specifications and an agreement to be signed between the project developer and

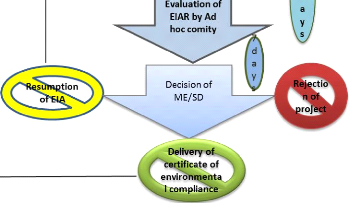

the BEEIA. Figure 3 below outlines the EIA administrative procedure in

Niger.

10

days 2 days

J

)

Project

Notification

screening

BEEIA

r,ppreciatjon: MESD

Figure 3: Administrative Procedure of Environmental

Impact Assessment in Niger

|

Preparation of TOR by developer in collaboration

with

BEEIA

|

Approval of TOR

by the

MESD/BEEIA

Realization of EIA and production of EIA report

(EIAR)

Admissibility assessment of EIAR by BEEEI

Lessons

learned J

W

implementation of project J

Monitoring and

control of ESMP

by

BEEIA

Implementation of

ESMP by the Developer

I

3--_

Autorization

Evaluation of

EIAR by Ad

hoc comity

Delivery of

ificate of

enviro enta I complian e

14

Source: Translated and adopted from Cisse

(2016)

15

3.1.3. Public Participation

Public participation in the EIA procedure in Niger is

legislated by Articles 10 and 11 of the Decree 2000-397 on the EIA procedure.

The publicity mechanism of the EIA is done through informing the population of

the eventuality of the project, consulting the people concerned by the project

during data collection for the elaboration of the EIAR, and making accessible

the EIA reports to the public at the BEEIA. Moreover, the decree states that

this population should be informed and concerted about the content of the EIAR

by all appropriate means. After approval of the project by the CA, the EIA and

the final decisions are consulted at BEEIA office.

3.1.4. Climate Change in Niger EIA legislation

No provision, neither the Ordonnance 97-001 nor the decree

2000-397, refers to the consideration of CC regarding impacts and mitigation or

enhancement measures during the implementation of a project. The project

mitigation measures are mentioned in Article 7 of the Decree 2000-397 but they

are related to biophysical and human components such as water, wildlife, air,

population health, etc., not global aspects such as CC. Nevertheless, there are

provisions related to the protection of the atmosphere and the fight against

global warming in Law 98-56 on the management of the environment (Article

37-41), but decrees on the application of that law are not yet adopted.

3.1.5. EIA Procedure Limits

3.1.5.1. Inadequate Public Participation

Article 11 of the Decree No. 2000-397 provides that» the

EIA reports and final decisions shall be consulted at the BEEIA office. Under

no circumstances can they be loaned and /or taken away by private

individuals». The Decree does not provide another mechanism for widespread

dissemination such as the posting of the draft report in the localities

concerned or a time period given for the public to express their comments or

concerns. In addition, only few institutions receive a copy of the EIA report

(article 8) and the remaining members of the ad-hoc committee do not receive

the final copy of the report after the project approval while international

best practices, in particular the World Bank Group standards, advice wide

publicity of EIAs (World Bank, 1999).

3.1.5.2. Environmental Monitoring Missions Funded by

the Project Developer

Although it has not been clearly stated in the legislative

texts, costs related to environmental monitoring are estimated in the

Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP), i.e., supported by the

developer. That could reduce the independence and impartiality of the BEEIA

staff conducting the monitoring.

3.1.5.3. Ambiguity Related to the Scope of the EIA as a

Tool

16

From the statement of Article 4 of Ordinance 97-001, it is

clear that EIA is compulsory both for projects and for development programmes.

This creates an amalgam with respect to the scope of both tools (EIA and

SEA).

3.1.5.4. Failure to Categorise Projects Subjugated to

EIA

The Decree No. 2000-398 / PRN / ME / LCD of October 20th, 2000

determining the list of activities, works and planning documents for which

environmental impact assessments are required does not classify the various

projects into categories. That does not allow knowing the ones that require a

thorough EIA, or a simplified EIA.

3.2. Assessment of the European Union Directive on

Environmental Impact Assessment

3.2.1. Presentation of the Environmental Impact

Assessment Procedure in EU

The current environmental impact assessment procedure in the

EU is governed by the Directive 2014/52/EU of the European Parliament and the

Council of April 16th, 2014 on the assessment of the effects of certain public

and private projects on the environment adopted from the amendment of the

Directive 2011/92/EU. It entered into force on May 15th, 2014. Member States

(MS) had to transpose it into their national legislation as from May 16th, 2017

at the latest and communicate to the European Commission the national

legislation adopted in order to comply with the directive.

According to Article 3 of the Directive, the EIA shall

identify, describe and assess the significant effects of a project on the

biophysical and social factors of the environment and the interaction between

them. Moreover, the effects of the project on the factors shall include the

expected effects like the vulnerability of the project to risks of major

accidents and/or disasters that are relevant to the project.

Two types of projects are under the scope of the Directive:

projects of Annex I having significant effects on the environment that should

be subject to a systematic assessment and projects of Annex II that do not

necessarily have significant effects on the environment in every case. For the

latter, the MS shall determine whether the project shall be made subject to an

assessment through a case-by-case examination or thresholds or criteria set by

them.

3.2.2. EU Environmental Impact Assessment Procedure

From the Directive, the important phases identified are:

screening, scoping, realisation of the EIA, assessment and evaluation of the

EIA procedure, granting or refuse of the development consent and the

determination of monitoring conditions. Because of its cross-cutting character,

public consultation is treated differently from the above mentioned phases.

17

3.2.2.1. Screening

The screening is the first phase that starts when the

developer notifies or informs the Competent Authority (CA) about his project

proposal for a request for development consent. If the project is listed among

those of Annex I for which an EIA is required, there is no need for screening.

For those listed in Annex II, the developer shall provide detailed information

on the characteristics of the project and its likely significant effects on the

environment. Based on the information provided by the developer, the CA shall

make its determination whether the project requires an EIA or not and states

the main reasons for requiring or not such assessment with reference to the

relevant criteria listed in Annex III of the directive( Article 4 (5)). The CA

shall make its determination within 90 days from the date of submission of all

the information required by the developer. In exceptional cases (nature,

complexity, size, location of the project), the CA may extend that deadline and

shall inform the developer in writing of the reasons justifying the extension

and of the date when its determination is expected (Article (4(6)).

3.2.2.2. Scoping

Where an EIA is required, the developer shall prepare and

submit an EIA report. This report shall include the minimum information as

listed in Article 5 (a to f). Where an opinion is issued about the description

of the project, the EIA report shall be based on that opinion, and include the

information that may reasonably be required for reaching a reasoned conclusion

on the significant effects of the project on the environment, taking into

account current knowledge and methods of assessment (Article 5(1)).

Where requested by the developer, the CA, taking into account

the information provided by the developer in particular on the specific

characteristics of the project, including its location and technical capacity,

and its likely impact on the environment, shall issue an opinion on the scope

and level of details of the information to be included by the developer. The CA

shall consult the authorities likely to be concerned by the project by reason

of their specific environmental responsibilities or local and regional

competences before it gives its opinion (Article 5(2)).

3.2.2.3. Realisation of the EIA

After the scoping is completed and the ToR are defined, the

developer carries out the EIA and submits the EIA report as required by Article

5 and other provisions of the directive related to the public participation or

trans-boundary issues to the CA.

3.2.2.4. Assessment and Evaluation of the EIA

Prior to the assessment and evaluation of the process, some

requirements are set to ensure the completeness and quality of the

environmental impact assessment report. Among those requirements:

18

y' the developer shall ensure that the environmental impact

assessment report is prepared by competent experts;

y' the CA shall ensure that it has, or has access as necessary

to, sufficient expertise to examine the environmental impact assessment report;

and where necessary, shall seek from the developer supplementary information,

in accordance with Annex IV, which is directly relevant to reaching the

reasoned conclusion on the significant effects of the project on the

environment;

y' Member States shall, if necessary, ensure that any

authorities holding relevant information make this information available to the

developer.

As the requirements mentioned above are made, the competent

authority assesses and evaluates the EIA report to decide about the granting or

refuse of the development consent.

3.2.2.5. Project Appraisal

When the results of consultations and the information required

in Articles 5 to 7 are gathered and submitted by the developer, the CA has to

decide about the granting or refuse of the development consent within a

reasonable period of time (Article 8a (5)).The decision of grant or refuse of

the development consent by the CA shall incorporate at least:

y' A reasoned conclusion on the significant effects of the

project on the environment, taking into account the results of the examination

of the information presented in the EIA report and any supplementary

information provided by the developer or through the public consultation;

y' Any environmental conditions attached to the decision, the

features of the project and/or mitigation measures envisaged, if possible,

offset significant adverse effects on the environment as well as, where

appropriate, monitoring measures.

3.2.2.6. Determination of Monitoring Conditions

In the case the development consent is granted the CA shall

determine the procedures regarding the monitoring of significant adverse

effects on the environment and sets the type of parameters to be monitored and

the duration of the monitoring which shall be proportionate to the nature,

location and size of the project and the significance of its effects on the

environment. Existing monitoring arrangements resulting from EU legislation

other than this directive and from national legislation may be used if

appropriate, with a view to avoid duplication of monitoring (Article 8a).

Figure 4: The EU EIA Procedure According to Directive

2014/52

Request for development consent

Project of Annex I

No screening

Scoping

Project of Annex II

Screening

Realization of EIA

Assessment &evaluation of the EIA

report

Project Appraisal

Project rejection

19

Monitoring conditions

20

3.2.3. Public Participation in EU EIA Procedure

The directive provides that the public concerned shall be

given early and effective opportunities to participate in the environmental

decision-making procedures and be entitled to express comments and opinions

when all options are open to the CA before the decision on the request for

development consent is taken (Article 6(4)). Moreover, the determination made

by the CA shall be available to the public.

Pursuant to Article 6(2), the public shall be informed

electronically and by public notices or by other appropriate means, of the

following matters early in the environmental decision-making procedures:

y' the request for development consent;

y' the fact that the project is subject to an EIA procedure

and, where relevant, the fact that Article 7 applies(if another member state is

concerned);

y' details of the CA responsible for taking the decision,

those from which relevant information can be obtained, those to which comments

or questions can be submitted, and details of the time schedule for

transmitting comments or questions;

y' the nature of possible decisions or, where there is one,

the draft decision; y' an indication of the availability of the information

gathered and submitted to the CA;

y' an indication of the times and places at which, and the

means by which, the relevant information will be made available;

The time-frames for consulting the public concerned on the EIA

report shall not be shorter than 30 days (Article 6 (7)). If the project is

likely to have significant effects on the environment in another Member State,

the public participation mechanisms detailed in Article 7 of the directive

shall be applied.

When a decision to grant or refuse development consent has

been taken, the CA shall promptly inform the public and the authorities likely

to be concerned by the project (Article 9). He shall make available the

following information:

y' the content of the decision;

y' the main reasons and considerations on which the decision

is based, including information about the public participation process( summary

of the results of the consultations and the information gathered; and how those

results have been incorporated or otherwise addressed) and the comments

received from the other affected Member State if it is the case.

3.2.4. Climate Change in EU Directive on EIA

The issues of CC are highlighted in many paragraphs of the

preamble but also in Annex III, and IV of the EU EIA directive. In addition,

the risk of major accidents and/ or disasters which are relevant to the project

concerned, including those caused by CC, in accordance with scientific

knowledge(Annex III,(1)(f)) is one of the criteria to determine whether the

projects listed in Annex II should be subject to an EIA.

21

Annex IV which refers to the information for the EIA report

also requests that the report shall contain a description of the likely

significant effects of the project on the environment resulting from the impact

of the project on climate such as the nature and magnitude of greenhouse gas

emissions and the vulnerability of the project to CC (Annex IV (5) (f)).

3.3. Assessment of the European Union Directive on

Strategic Environmental Assessment

The European Union Directive on Strategic Environmental

Assessment is the Council Directive 2001/42/EC on the assessment of the effects

of certain plans and programmes on the environment adopted on June 27th, 2001

and entered into force on July 21st, 2004. The purpose of the directive

(Article 1) is to provide a systematic framework for considering the

environmental effects of public sector plans and programmes, and to provide a

high level of protection for the environment, as well as to contribute to the

integration of environmental considerations into the preparation and adoption

of plans and programmes, with a view to promoting sustainable development.

In pursuance of Article 12(3) of the Directive7,

the application and effectiveness of the directive has been assessed and a

first report was sent by the Commission to the European Parliament and Council

in 20098. In addition, a study on MS' progress and challenges

experienced in the application of the SEA Directive for the period 2007-2014

was also carried out in 20169 in order to prepare the second

report.

3.3.1. Limits of the EU SEA Directive

The SEA Directive does neither provide detailed specifications

about the procedures for public consultation nor clarifying the methods of

communication with the public even though it states that it is the

responsibility of every Member State to determine the detailed arrangements for

the information and consultation of the authorities and the public (Article

6(5)).

Regarding the integrating of CC issues, the shortcomings that

have been raised from the report on the application and effectiveness of the

SEA Directive are the lack of a well-established methodology to determine

impacts related to CC and the inexistence of specific guidance to CC issues. In

fact, these issues are considered in SEA Directive on a case-by-case basis

concerning some plans and programmes with a potential significant impact on the

climate such as energy and transport (Article 3). Moreover, Annex

I of the directive which refers to the information to be

provided in the SEA environmental report includes `'climate factors» but

does not provide further details about how the vulnerability of the plans and

programmes to CC or theirs impacts on CC can be assessed.

7 Article 12(3): Before 21 July 2006 the Commission shall send

a first report on the application and effectiveness of this Directive to the

European Parliament and to the Council.

8 report from the commission to the council, the European

Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the committee of the

regions on the application and effectiveness of the directive on strategic

environmental assessment (directive 2001/42/EC), Brussels, 14.9.2009 COM(2009)

469 final.

9 Study concerning the preparation of the report on the

application and effectiveness of the SEA Directive (Directive 2001/42/EC) Final

Study. European Union, 2016.

22

4. COMPARISON OF ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT

PROCEDURE IN EUROPEAN UNION (EU) AND NIGER

4.1. Criteria for Comparison

As mentioned before, there is no legislation or guideline

regarding the SEA in Niger. That is why the comparison concerns only the

European Union EIA Directive and the Niger Legislation on EIA. It is carried

out based on the review of literature on theory and concept of mainstreaming CC

in EIA and considering the key steps in the Procedure. The comparative analysis

identifies the steps of the EIA procedures in which CC issues are taken into

consideration.

These steps are: (1) screening, (2) scoping, (3) assessment

and evaluation of the EIA, (4) project appraisal and (5) monitoring

conditions.

The comparative study aims to highlight the similarities and

differences with related to CC and EIA legislation in EU and Niger in the five

steps cited above.

4.2. Results

Table 1 shows that the EU EIA Directive 2014/52 requires the

CC mainstreaming in the three steps out of five chosen for the comparison i.e.

the screening, scoping, and assessment and evaluation steps even though it does

not provide any specific requirement regarding CC in the project appraisal and

the project monitoring steps.

In contrary, Niger Legislation on EIA does not provide any

requirement regarding CC mainstreaming in EIA procedure in the five steps

considered for the comparison.

23

Table 1: Comparison of EU EIA Directive and Niger

Ordinance 97-001 on EIA and its Decree 2000-397 on Administrative

Procedure

|

CC mainstreaming in EIA steps

|

EU Directive 2014/52

|

Niger Ordinance Decree 2000-397

|

97-001

|

and

|

|

Screening

|

The risk of major accidents or disasters, including those

caused by CC is one of the criteria to determine whether the projects listed in

Annex II should be subject to an EIA

|

Nil

|

|

|

|

Scoping

|

A description of the factors likely to be significantly affected

by the

project including climate (GHG emissions, impacts relevant to

adaptation); and the impact of the project on

climate and the

vulnerability of the project to CC are required (Annex

IV)

|

Nil

|

|

|

|

Assessment and Evaluation of

EIA Procedure

|

The Competent Authority assesses and evaluates the EIA based

on the information required in Annex IV recalled during the scoping.

|

Nil

|

|

|

|

Project Appraisal

|

Nil

|

Nil

|

|

|

|

Monitoring Conditions

|

Nil

|

Nil

|

|

|

24

4.3. Discussions

The comparison of EIA legislations has enabled us to note two

completely different systems, on the one hand, Ordonnance 97 001 and its

implementing Decree 2000-397 of Niger which do not include any provision

related to CC considerations in the EIA procedure and on the other hand, EU

Directive 2014/52 which requires that these aspects be taken into account not

only when defining the criteria for screening but also in the scoping and the

assessment and evaluation of the EIA report by the Competent Authority. Though

the EU Directive entered into force few years ago (2014), the MS had until May

2017 to transpose it into their national legislation.

Nevertheless, the adoption of the directive that takes into

consideration CC itself constitute an important step to enabling GHG awareness

of projects subjected to EIAs, assisting proponents in managing or reducing

risks associated with CC and ensuring the public that CC issues are considered

in projects development. However, neither changing climatic parameters nor

thresholds or limits of GHG emissions requirements concerning the environmental

assessment of projects in the EIA have been explicitly mentioned in the EU

Directive. That opening could lead MS to have different views on the degree to

which and how GHG emissions should be assessed and controlled in each project

but a review of previous EIAs conducted under the former directive and national

legislations could help them to understand these views and identify reasonable

and practical approaches to GHG emissions at the project level.

As pointed out in the previous chapters, the implementation of

this new paradigm is a major challenge to overcome despite the tendency that CC

will continue to harm the environment and jeopardize economic development. One

of these challenges is how to link the GHG emissions from an individual project

to their impact on CC because of the huge gap in scale between the global

climate and the local climate affected by individual project.

Despite the challenges raised, it is probable that an

appropriate assessment of the impact of project on climate and its

vulnerability to CC would lead to propose proper mitigation measures and

consequently enhance the project's sustainability and lifespan considering the

need for mainstreaming the climate change in environmental assessment is

increasingly expressed worldwide.

5. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Conclusions

Nowadays, incorporating CC considerations in Environmental

Assessment is largely recognised as a way for determining whether PPP are

consistent with legal framework CC policies and international commitments and

initiatives to manage GHG emissions but also a mean to assist proponents in

using best practices that adapt to possible CC impacts, such as changes in the

frequency or intensity of extreme weather events, increases in mean

temperatures or altered precipitation patterns and amounts.

This paper

25

discussed on how CC issues are addressed worldwide through

environmental impacts assessment (EIA) and strategic environmental assessment

(SEA) in planning processes with a focus on the European Union legislations in

order to identify perspectives for Niger. It also compared the current EIA

legislation in EU and Niger to identify differences, and similarities related

to CC mainstreaming in EIA in order to learn lessons and to propose some ways

of improvement. The assessment of the two legislations revealed that while the

EU Directive made provisions about the assessment of the impacts of the

projects on CC as well as the vulnerability of the projects to CC, the Niger's

EIA procedure follows the traditional approach of undertaking EIAs, which only

focuses on the assessment of the impacts of proposed projects or activity on

the environment. Moreover, CC mainstreaming is not sufficiently considered in

the SEA Directive as the directive does not provide a well-established

methodology and specific guidance for determining CC impacts and Niger EA

legislation does not have any provision about SEA procedure.

It emerged from this study the need for an establishment of

clear defined legal provision on SEA incorporating CC and a revision of

Ordonnance 97-001 of 10 January 1997 on the institutionalisation of

environmental impact assessments and its implementing decrees 2000-397 and

2000-398 to not only incorporate CC in the EIA procedure but also clarifying

the scope of the EIA, categorising projects according to their scope and

nature, improving the coordination mechanism of the EIA procedure, public

participation and financing of environmental monitoring.

Recommendations

The following recommendations are proposed to the ministry in

charge of the environment of Niger.

1. Update the EIA legislation which shall provide clearly

defined criteria and checklists for screening and scoping environmental impacts

to ensure identification of the significant CC impacts on the proposed project

or activity in line with the other national legislations on CC.

2. As mainstreaming CC in EIA procedure is a new concept for

many practitioners, establishment of clear criteria governing the

qualification, skills, knowledge and experience which must be possessed by

persons conducting EIA and government experts who review and assess EIAs

procedure and reports. This approach may be used to ensure that persons

conducting EIAs and assessing CC impacts possess the requisite qualification,

skills, knowledge and experience on CC and adaptation policies and measures.

3. Elaborate and submit to government a new SEA bill taking

into account CC and its implementing decrees regarding the administrative

procedure and types of plans and programs subject to SEA.

4. Provide a clear mechanism of public participation in

addressing CC and its effects and developing adequate responses in EIA and SEA

procedures as required by UNFCCC (Article 6 (a) (iii)).

26

ACTION PLAN FOR THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE

RECOMMENDATIONS

For the above-mentioned recommendations to be effective, it is

important to define the different stakeholders and their responsibilities for

the implementation of the actions. The proponent of the project for the

revision of Ordonnance 97-001 on EIA and its implementing decrees and the

proposal of a new draft bill on Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) taking

into account the CC dimension, will be the ministry in charge of the

environment which has under its responsibility the Bureau of Environmental

Evaluation and Impact Assessment (BEEIA):

However, there are also other key stakeholders such as the

General Directorate of Environment and Sustainable Development (DGEDD), the

National Council of Environment for Sustainable Development (CNEDD), other

sectorial ministries, the Technical Committee for Verification and Evaluation

of Texts (COTEVET) of the General Secretariat of the Government,

parliamentarians members of the Environment and Rural Development Commission

and civil society (NGOs and Consultancy firms) working in the field of

environment and environmental assessment.

It is also important to recall that the review and drafting of

legislative and regulatory texts require the involvement of experts in this

field, in particular environmental assessment experts and jurists, and is

mainly conditioned by the availability of the necessary financial resources to

achieve the assigned objectives. Therefore, the recruitment of a consultant for

the revision and elaboration of these texts is essential. With regard to

financial resources, the State's budget and other partners of the ministry in

charge of environment are the potential sources of funding for this project.

Roles and responsibilities of stakeholders

1. Bureau of Environmental Evaluation and Impact

Assessment (BEEIA)

The BEEIA, which will serve as the institutional anchorage of

the initiative, in collaboration with the DGEDD and the CNEDD will be

responsible for the elaboration of the terms of references for the study, the

recruitment of the consultant and follow-up of all actions in order to achieve

the implementation of these recommendations.

2. Sectorial Ministries and Civil Society

Sectorial ministries and civil society will be involved in

data collection for inputs, drafting of texts and also during pre-validation of

elaborated texts by the consultant at a workshop to be organized for the

occasion.

3. Technical Committee for Verification and Evaluation

of Texts (COTEVET)

This committee housed in the General Secretariat of the

Government has an important role to play in this project because it is

responsible for verifying and evaluating the conformity of all bills or decrees

with the constitution and other laws of the Republic before passing them to the

government for adoption. In this

27

project, they will be sensitised about the need to integrate the

climate dimension into the environmental assessment tools and the deficiencies

hitherto found in the implementation of the existing texts.

4. Members of the Environment and Rural Development

Commission

These parliamentarians will be sensitized on the ins and outs of

these draft texts and the integration of the CC dimension in the environmental

assessment tools so that they defend and facilitate their adoption by the

National Assembly.

The Different Actions to be carried out:

The table 2 below gives details of the actions to be taken, the

responsibilities of the stakeholders for the implementation and the risks.

28

Table 2: Actions to be carried out for the Implementation

of the Recommendations

|

Actions

|

Responsables of actions

|

Risks

|

1. Elaboration draft texts by the

consultant

|

Consultant

|

- Administrative slowness

- lack of interest of the targeted actors

-lack of financial resources to carry out the actions

-mismatched schedule with the parliamentarians agenda

|

2. Two-day pooling workshop to collect

comments on draft

texts

|

BEEIA/DGEDD/CNEDD

|

|

Consultant

|

|

BEEIA/DGEDD/CNEDD

|

|

BEEIA/DGEDD/CNEDD

|

|

|

|

|

|

BEEIA/DGEDD/CNEDD

|

|

29

References:

Agrawala,S., A.Kramer, G. Prudent-Richard et al. (2010):

Incorporating CC impacts and adaptation in Environmental Impact Assessments:

Opportunities and Challenges. OECD Environmental Working Paper No. 24, OECD

Publishing, (c) OECD. doi: 10.1787/5km959r3jcmw-en.

André, P., B. Enserink, D. Connor and P. Croal (2006):

Public Participation International Best Practice Principles. Special

Publication Series No 4. Fargo, USA: International Association for Impact

Assessment.

CEAA-Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency (2003):

Incorporating CC Considerations in Environmental Assessment: General Guidance

for Practitioners. Published by the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Committee on

CC and Environmental Assessment. Catalogue No. En106-50/2003E-PDF ISBN

0-662-35454-0. Available on

www.ceaa-acee.gc.ca

CARICOM-Caribbean Community et al. (2004): Adapting to a

changing climate in the Caribbean and South Pacific regions. Guide to the

integration of CC adaptation into the environmental impact assessment process.

Caribbean community secretariat, Adapting to CC in the Caribbean Project.

Chaker, A., K. El-Fadl, L. Chamas, and B. Hatjian (2005): A

review of strategic environmental assessment in 12 selected countries.

Environmental Impact Assessment Review 26 (2006) 15- 56. Available online on

www.sciencedirect.com.

Cherp, A (2001): Environmental assessment in countries in

transition: Evolution in a changing context. Journal of Environmental

Management (2001) 62, 357-374 doi:10.1006/jema.2001.0438. Available online at

http://www.idealibrary.com.

Cissé, H (2013): Intégration de la

biodiversité dans l'évaluation environnementale

stratégique des aménagements dans le bassin fluvial du programme

kandaji au Niger. Thèse présentée comme exigence partielle

du doctorat en sciences de l'environnement. Université du Québec

à Montréal. 352 pages.

Cissé, H (2016): Intégration de la

Biodiversité dans les évaluations environnementales au Niger.

Journée mondiale de la Biodiversité, Mai 2016.

Présentation Powerpoint du Bureau d'Évaluation Environnementale

et des Études d'Impact, Ministère de l'Environnement et du

Développement Durable.

CNEDD-Conseil de l'Environnement pour un Développement

Durable (2006) : Programme d'Action National pour l'Adaptation aux changements

climatiques .90 pages

Dalal-Clayton, B., and B. Sadler (1999): Strategic

environmental assessment: a rapidly evolving approach. International Institute

for Environment and Development. Environmental planning issues no. 18, 1999.13

pages.

Hallegatte S., F. Lecocq, and C. De Perthuis (2011): Designing

CC adaptation policies: an economic framework. The World Bank, Washington, DC,

pp 1-39.

Thomas, B. F., C. Wood, and C. Jones (2002): Policy, plan, and

programme environmental assessment in England, the Netherlands, and Germany:

practice and prospects. Journal: Environment and Planning B:

IAIA-International Association for Impact Assessment (2009):

What Is Impact Assessment? 4 pages. Available at

https://www.iaia.org/uploads/pdf/What_is_IA_web.pdf.

IFAD-International Fund for Agricultural Development (2013):

Niger, Évaluation Environnementale et des Changements Climatiques pour

la préparation du Programme d'Options Stratégiques pour le Pays

20132018 du FIDA. Rapport principal. 53 pages.

INS-NIGER -Institut National de la Statistique du Niger (2014):

le Niger en Chiffres 2014. 84 pages.

Larsen, S., L. Kørnøv, P. Driscoll (2013):

Avoiding CC uncertainties in Strategic Environmental Assessment. Environmental

Impact Assessment Review 43 (2013) 144-150.