|

LABIDI Myriam

|

Date de création :

|

01.12.2005

|

|

Date de dépôt :

|

03.01.2006

|

|

Niveau :

|

BAC + 6

|

LEVERAGING SUPPLIERS RELATIONS

THROUGH THE USE OF INFORMATION AND

COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGIES:

The evolution of the supplier role in the

aerospace and automotive indus try

Airbus tutor: Miss Celine Dedieu Airbus Trainee: Labidi

Myriam

ESC Toulouse tutor: Mr Philippe Malaval Written in

November 2005

CONTENTS

General Introduction: Supply Chain Management

· Main Aspects and Characteristics of the Supply

Chain

· Material Flow

· Information Flow

· Buyer-Sellers Relations

· The Organization Goals Definition

· Supply Chain Planning

· Supply Chain Execution

· Strategic Procurement

Part I: Supplier Relationship Management, the extension

of Supply Chain Management

1. The SRM concept

1.1 The Technical enablers

1.2 Customer service and support: SRM support functionalities

1.3 SRM and Purchase 1.4 SRM and Marketing 1.5 Conclusion

2. Concrete Example: Boeing and the evolution of the

supplier role

2.1 Boeings transformation into a large parts and systems

integrator

2.2 The 787 Dreamliner program: the elevation of suppliers status

from provides to partners 2.3 The new supplier model: linking the supply

chain

Part II: E-commerce exchanges

1. The three e-exch ange models

1.1 Public e-marketplaces

1.2 Industry-sponsored marketplaces or consortia 1.3 Private

exchanges

2. Industry-sponsored marketplace

infrastructure

2.1 Capital investment 2.2 Participant volume 2.3 Industry-

sponsored marketplace functionnalities

3.

Private exchanges structure and functionalities

3.1 Private exchanges structure

3.2 Private exchange functionality

3.3 Private exchange value creation: the Daimler Chrysler supply

chain network example

4. Choosing between Industry sponsored marketplace

and private exchange

4.1 Sustainability of Industry-sponsored marketplaces and private

exchanges 4.2 Identification of the processes to be adressed

4.3 Value metrics to be adressed

4.4 Comparison between the development and management costs 4.5

The best practices:

· Change process: the compu!sory partnership

· A so!id business mode!

· Adding value beyond the too!s

· Customer service

· Focusing on the value proposition

· Review of the interna! processes

5. Concrete example: the aerospace exchanges

solutions

5.1 Exostar, the BAE Systems, Boeing, Lockheed Martin and

Raytheon emarketplace 5.2

MyAicraft.com

5.3 Exostar and Myaircraft potential risks

5.4 The GE Aircraft Engines position toward Exostar

Part III Quality and e-commerce, control and enhancement

of the supplier performances

1. Why quality is such a crucial stake?

1.1 The certification process: a quality communication mean 1.2

The ISO norms in the industry

1.3 Implementation of ISO 9001:2000

1.4 Certification, a prerequisite for B2B e-commerce

· Conformity assessment and assurance in e-commerce

· ISO 9000 certification and Internet e-commerce

· Ensuring online security and authencity

2. The aerospace quality strategy

2.1 The AS9000 standard

2.2 AS9100: the first international quality systems aerospace

standard

2.3 Industry managed processes: demonstration of the supplier

compliance

2.4 The Quality System Audits: the aerospace industry control

other party processes 2.5 The Oasis database: a new aerospace

procurement tool?

TRAINING PERIOD OVERVIEW AND

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

As an Airbus trainee I had the opportunity to work for the

Procurement Quality International (PQI) section of Central

Airbus Entity. This subsection of Procurement mainly deals with quality issues.

To that purpose, internal work must be done with the Airbus Quality Responsible

as well as external work with the Supplier Quality Responsible.

This training period gave me the chance to understand how

quality control is conducted in the aerospace industry. In addition to this

overview, I get a real insight of the aerospace OEMs and supplier needs with

regard to quality issues. I also get a deep knowledge of ICT tools deployment

in a large company.

I was mainly in charge of the relationships with suppliers

concerning the use of a collaborative platform. To that regard, I did some

administrative work, meaning that I assured full completion of the registration

process by the supplier. I also produce some communication documents, which

were helping suppliers to understand the outputs and inputs of the

collaborative platform. It was also needed to give some technical guidance

through mail or phone calls. As communication was also conducted among Airbus

employees, I was in charge of producing communication documents for the

internal usage.

Related to the registration process some reporting was done

especially during the PQI meetings. As a matter of fact, some key quality

indicators were provided. They allow the measuring of the adoption level of the

collaborative platform by the suppliers. These indicators also help the team to

take corrective actions or to enhance the best actions.

All the work described above allows the cleaning up of the

suppliers' repository database used by the Airbus employees. I also take part

into the collaborative work done by one Airbus responsible with the European

Aerospace Quality Group.

With regard to technical issues, I worked in collaboration

with the support staff of the collaborative platform. I was in charge of

explaining the difficulties encountered by the external and internal users of

the platform. To that purpose written reports explained the users needs and

even propose other solutions.

In addition to the collaborative work done with the support

staff, we also had to coordinate our efforts with the other departments. The

holding of different meetings ensured that we were following the same road.

Considering the main tasks conducted during my training

period, I've decided to write over the link between the transformation of the

supplier role and the use of Information and Communication Technologies.

Throughout this paper we try to demonstrate the shift in the roles of suppliers

and how the tools provided by the Information and Communication Technologies

(ICTs) enhance the collaboration in the aerospace and automotive industry.

Considering the similarities between the automotive and aerospace supply chain,

we decided to illustrate theory with vivid examples taken from both industries.

In order to some useful benchmarking, we also decided to focus on the Boeing

practice. We most particularly examine the e-tools, which are used by the

Airbus competitor.

The main goal of this paper is to convince the readers that

concepts such as supply chain management and supplier relationship management

are not useless theories served by costly and sophisticated e-tools. We try to

demonstrate that the e-tools available can create value when implemented in the

best manner.

Considering the new face of competition, the relationship

with suppliers is no longer the same indeed. We would like to prove that the

combination of the top management vision and the use of the most appropriate

e-tools alleviate the supplier relationship to a real and highly valuable

collaboration. We even conclude that firms, which can consider themselves as

networks are adopting the "extended enterprise" business model.

We begin to introduce the discussion by explaining how supply

chain management goes beyond production and logistics functions. To that

purpose, we try to underline how supply chain management leads to a value chain

approach. Then, we examine how Suppliers Relationship Management e- tools

enabled a better collaboration with the best suppliers.

The second part of this paper focus on the two main models of

e-commerce exchanges, which are used in both automotive and aerospace industry.

In order to do that, we detail the structure and functionalities of both

exchanges. Then, we decided to explain the best practices in the case of

e-commerce exchanges adoption and implementation.

As quality is a key issue for both OEMs and suppliers in the

aerospace industry, we decided to explain the industry approach of these issues

and and its link with ICTs.

GLOSSARY OF TERMS

AECMA: European Association of Aerospace

Industries

EDI: Electronic Data

Interchange, the transfer of data between different companies

using networks, such as the Internet. As more and more companies get connected

to the Internet, EDI is becoming increasingly important as an easy mechanism

for companies to buy, sell, and trade information

E- RFx: e-request for qualification

ERP: Enterprise Resource Planning. An

amalgamation of a company's information systems designed to bind more closely a

variety of company functions including human resources, inventories and

financials while simultaneously linking the company to customers and

vendors.

FAA : Federal Aviation Administration

FAR: Federal aviation requirements

ISO: International Organization for

Standardization OEM or PRIMES: Original equipment

manufacturer

OTHER PARTIES: Independent organisations

engaged in audit and certification activities that are under control and

oversight of aerospace industry. They are industry managed

SECOND SHARED PARTIES: European association

called ASD EASE in charge of assessing Suppliers QMS, applying the same

assessment rules, and sharing the assessment results between its members. They

are industry managed

THIRD PARTIES: Independent organisations

engaged in audit and certification activities that are not under control and

oversight of aerospace industry. They are not industry managed

XML: Extensible Markup

Language is a specification developed by the W3C. XML is a

pared-down version of SGML, designed especially for Web documents. It allows

designers to create their own customized tags, enabling the definition,

transmission, validation, and interpretation of data between applications and

between organizations.

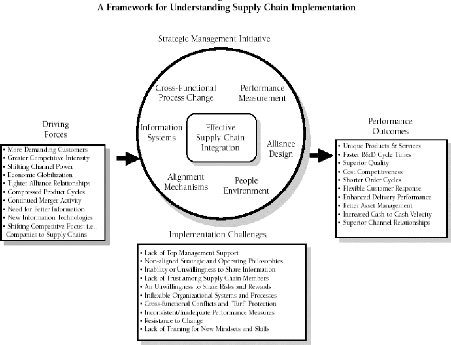

GENERAL INTRODUCTION: Supply chain

management

"As the economy changes, as competition becomes

more global,

it's no longer company vs. company but supply chain

versus

supply chain."

Harold Sirkin, VP Boston Consulting

Group

Recently, the global market schemes have generated new

concepts and mechanisms in various economic and industrial sectors. In the

complicated global market place, "Core Competencies" of each enterprise empower

their competitive advantages. Thus, the focus of various organizations is

directed to their core competencies. For this reason, they try to manage their

internal and external resources comprehensively. This orientation to

integrating different parts of a business or a production process causes each

industry to move initially toward Computer Integrated Manufacturing (CIM).

Thereafter, they have evolved into Computer Integrated Business (CIB). More

recently, they have grown into Extended Enterprise (Browne et al.,

1996).

As a result, modern managers are engaged more and more in the

processes of Decision Making (DM) and are forced to consider all factors within

the walls of their factories, as well as external factors with a holistic

perspective. This led to Supply Chain (SC) systems or more generally, Value

Chain (VC) and Value Stream (VS) approaches. SC, VC and VS concepts and

definitions, as a total system, have been investigated by many researchers at

universities and academic centers, as well as by professionals in

industries.

The first concern of a supply chain and a value chain is

generally the purchasing process. In such cases, the focus is on the supplier

selection, supplier evaluation and relational activities with sellers. In a

larger perspective, upstream suppliers are considered as a part of a

manufacturing/ buyer enterprise. Buyers usually plan and control their systems

and link them to their suppliers. Tiers or levels of suppliers form a supply

network, with the buyer managing and leading it in an integrated way.

Finally, supply chain management leads to a value chain

approach, in which all the affecting elements related to the customer(s) are

considered and analyzed in a broader view. In this approach, manufacturers and

distributors are included in the chain. In general, a supply chain is defined

as follow: "A supply chain is the network of facilities and activities that

performs the functions of product development, procurement of material from

vendors, the movement of materials between facilities, the manufacturing

products, the distribution of finished goods to customers, and after-market

support for sustainability."

Based on this definition, such a network in a system contains

a high degree of imprecision. This is mainly due to its real-world character

and its imprecise interfaces among its factors, where uncertainties in

activities from raw material procurement to the end user make the SC

imprecise.

· Main Aspects and Characteristics of the

Supply Chain

SC systems can be studied and analyzed from several

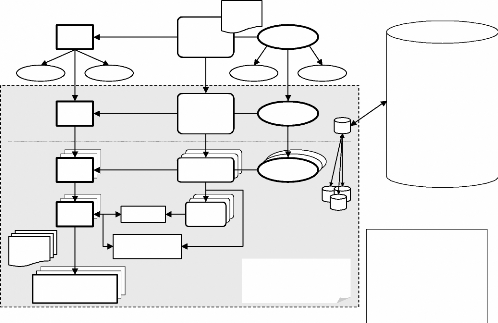

viewpoints. There are three major perspectives of SC systems: (1) "Material

Flow", (2) "Information Flow", and (3) "Buyer-Seller Relations". Apart from

these three aspects of SC systems, there are some other building blocks for

these systems, such as raw material suppliers, manufacturers of parts,

assemblers, Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs), distributors, retailers,

customers, etc. It should be noted that these aspects examine the SC and all

its components in an integrated way.

· Material Flow

Manufacturers should manage their supply resources to meet

customer needs. As a matter of fact, today an integrated management of the

material flow through different levels of suppliers and distributors is

challenging for managers.

Production planning in different sections of a manufacturing

enterprise and planning its upstream and downstream activities in a harmonized

way are two of the main tasks of managing the flow of materials in an SC.

Synchronizing production planning of each entity and, in a

more detailed way, scheduling production lines or job shops in these components

of the SC are very complicated and often intractable. This complication can be

highlighted if we investigate this chain from a product-oriented point of

view.

Consider a product structure or a tree. In the real world,

each level of the product tree is assigned to a supplier. A production plan for

such a product , which uses, e.g., the MRP approach, determines a due date for

each level and each component. When all of these components are produced in one

factory, the problem is easier to solve. However, when these levels expand

through a chain of suppliers, synchronizing them is usually very complicated,

while this synchronization is an obligation in Customer-Driven Manufacturing

(CDM). Clearly, a successful plan critically needs supportive logistics.

Transportation planning, inventory management and quality assurance activities

are some logistics in the smoothing flow of materials through the SC. These

logistic activities should be managed in an integrated way.

· Information Flow

The managing and control of each system comprise several

parts. In an SC system, information management is an essential sector.

Complexities in business planning activities occur in four areas: (a)

technological revolution, (1) product changes, (2) research and development,

and (3) information explosion. The SC system could be seen as a business

enterprise with a high level of data transaction. As a matter of fact, a

well-organized information system is a foundation for a proper material flow in

the SC.

· Buyer-Seller Relations

The buyer-seller relation is the main aspect of an SC. While

traditional approaches to the buy-sell process focus on factors like the price

in the buyer-seller relation, the SC draws attention to quality, R&D, cost

reduction, customer satisfaction, and partnerships. In an SC, both external and

internal resources are important. Consequently, the relations are not

established based just on the price and cost.

In the design of new products, for instance, Early Supplier

Involvement and Concurrent Engineering are new concepts, which are applied to

the SC and lead it to a holistic and comprehensive approach. Some other aspects

of the SC, which make it different from traditional approaches are long-term

contracts with suppliers and distributors, emphasizing the value adding

activities, strategic alliances and information sharing.

· The Organization Goals

Definition

Designing and implementing a supply chain management strategy

cannot take place until an overall company business plan or strategic plan has

been determined. In the planning hierarchy, the business plan or strategic plan

is the roadmap for the direction of the company. Just as you would not begin a

car trip to a new destination without a map and directions, so too should your

company develop its own plan or roadmap as to where it wants to be in 2, 5 or

even 10 years.

1 Achieving World-Class Supply Chain Alignment: Benefits,

Barriers, and Bridges by Stanley E. Fawcett Department of Management

Marriott School of Management Brigham Young University and Gregory M. Magnan

Albers School of Management Seattle University CENTER FOR ADVANCEDPURCHASING

STUDIES2001, p8

It is important to define a company's strategy in the context

of the broader market. An examination of customer's long-range business plans

can give an indication of the anticipated market movement and what their

position will be, as well as what is necessary to be a supplier to them. This

information is usually available for those companies that are able to and

willing to take the time to meet and talk to their customers and especially

their prospective customers, those who are not yet customers but represent the

targeted market. It is also vital to keep a business plan or strategy current.

Because markets and customers rapidly change their expectations, so to must a

business plan or strategy be flexible and take into account the fluidity of the

markets. In fact, a business plan is never truly finished unless an

organization is winding up its operations.

The resources required to push the organization in the

strategic direction indicated by the business plan must be identified. The

primary resource requirements that will need to be determined are people and

human resource requirements, financial requirements, infrastructure (both

physical and technological) requirements and partner or supplier requirements.

When looking out over a period of years it will be difficult to determine

exactly what and how many resources will be required to implement a business

strategy. However, it is still important to match and plan the acquisition or

addition of resources necessary for the strategy as a check on plan credibility

and costs.

The resources identified by the company as necessary to the

strategic plan should be those sought or valued by the desired customer and

market base. For example, if a company sets aside substantial sums for adding

an Enterprise Resource Planning platform, it should be certain that the

software will improve the capability of the company to service its target

market. A company must also be certain it is providing options desired by its

current and prospective customers when adding capacity, services or products.

It is important to note that when examining the importance of resources in

executing a business plan or strategy it is necessary to look at the target

market, which may or may not include the current customer base or market.

Implementation of a business strategy requires the

understanding of supply chain management. That is the reason why it is

important to set a definition of supply chain management. Stanford University's

Global Supply Chain Management Forum states the following, "Supply

chain management deals with the management of materials, information and

financial flows in a network consisting of suppliers, manufacturers/producers,

distributors and customers".

Long-range planning for supply chain activities must be linked

with the planned activities of marketing and sales to ensure that the necessary

resources and processes are in place to support anticipated customer demand.

In order to gain efficiency, the company strategic planning

must include supply chain management at an early stage. With regard to supply

chain activities, long-range planning must link it with the marketing and sales

activities in order to support anticipated customer demand.

Sales and Operations Planning is the cohesive operational

strategy that supports the companies business strategy. It provides the means

to incorporate, both supply chain management, sales and marketing. Based on

realistic and achievable forecasts, the Sales and Operations Planning provides

the company plan. Supply chain management activities cannot be maximized if

they are conducted without long-term strategy coordination with the other

functional areas in the organization. It seems that planning is an essential

stage in supply chain management and execution.

Good forecasting is also essential as it enables the

operations function to define the best balance between the available resources

and the anticipated demand. Forecasting also allows to plan, predict and

anticipate future market demand. As customers expect more and more from their

suppliers, it is important to share schedules and forecasts with suppliers. It

should allow suppliers to use a customer's forecasted schedule and to adapt

their organizations. This forecasted schedule helps to avoid the so-called Bull

Whip Effect, which is the distortion between the end-customer demand and the

supply chain activities. The Bull Whip Effect often result from the lack of

coordinated and shared information in the supply chain which is amplified by

the forecasting of suppliers on customer's forecasts. As customer's forecasts

are rarely 100% reliable, forecasting on it should increase the Bull Whip

Effect

· Supply Chain Execution

Supply chain management enables the company to execute its

strategy through operations and process. Consequently, Supply chain management

organises the following operations:

- Production planning and scheduling

- Procurement of raw materials

- Production of goods

- Delivery to customer

Implementing supply chain management at the fist stage of the

Sales and Operations Planning allows the best use of resources. As a matter of

fact, poor asset utilization, bloated inventories, poor on time deliveries,

high shipping and storage costs and low quality often reveals poor planning

rather than poor execution.

Various tools such as Lean manufacturing, Just-In-Time, Total

Quality Management and strategic inventory management ensure the most efficient

and responsive production system, meaning that you use and have no more than

what you need at any given time. These tools focus on the reduction of change-

over times in order to produce smaller lots without substantial cost

difference.

The automotive and aerospace industries were the first ones to

lean out their supply chain. For instance, Toyota was one of the pioneers in

the Just-In-Time and lean production use within its

manufacturing systems. Toyota lowers its

production costs through the use of Total Quality Management (TQM). Total

Quality Management means that the company drives its quality principles into

its suppliers and even their suppliers' suppliers. The implementation of TQM

ensures that only quality products were delivered to Toyota assembly lines.

Therefore, the quality defects number was significantly reduced. As Toyota cars

were of higher quality at cheaper prices, Toyota was enabled to took market

share away from the American automotive companies and to develop brand value in

the United States

Boeing tried to copy the automotive model of production.

Boeing has tried to push quality up the supply chain to its suppliers. In

larger suppliers such as Honeywell Aerospace, this has even led to the

formation of on-site supplier development teams that assist suppliers in

reducing costs, lead-times and quality defects in exchange for long-term

agreements, year over-year price reductions and cost savings sharing from the

direct work of the consulting teams. The result has been that suppliers who

have participated in this program have seen higher volumes, revenues and more

predictable demand while Honeywell and Boeing, have seen lower costs, better

quality and better delivery.

Technologies such as Electronic Data Interchange

(EDI), Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP),

Manufacturing Resource Planning (MRPII) and Material

Requirements Planning (MRP) play a key role in the execution

of company operations. These technologies even change the way business is

conducted. For instance, in the automotive industry Chrysler, Ford and General

Motors put in place a common platform for EDI. In order to minimize on-floor

inventory and cash outflow, the automotive assemblers require hourly deliveries

by their suppliers. Consequently, the EDI platform main goal was to allow the

sharing of schedules both from the automotive company to the supplier and from

the supplier to the automotive company.

Being a player in the global marketplace means that the

company is enabled to access, to receive and send information. However, in

order to ensure the better use of the different technologies described, it must

be possible to automate proper internal processes meaning that they must yield

good information and results. These strategies of partnerships must be built on

trust and imply sharing of information. In addition, the exchange and

management of information must not be an undue burden for the participants.

Supply chain management cannot be considered solely as a cost

cutting tool. As a matter of fact, without direction cost cuts should impact

the services, which are valued by the customers.

· Strategic Procurement

When companies look to implement a strategic procurement

program, they should again look at what their customers should truly value and

try to shape the supply chain within their influence to meet those value

expectations as efficiently as possible.

Quite often Strategic Procurement is considered as the way to

get the lowest price from suppliers. However, it seems that the savings

generated this way are limited. As a matter of fact, companies that have

focused on developing relationships with only a few strategic suppliers have

saved significantly more in the long run.

According to the study conducted by the Golden Gate University

in California (1992) and the Mc Kinsey study (1997), purchased goods and

services could account for 50 to 80 percent of a company's

expenditure. With so much product value tied up in the costs of

procurement, the implementation of a lean supply chain strategy implies an

effective and planned partnership with suppliers.

Implementation of a strategic procurement program implies the

reshaping of the supply chain according to the value expected from the

customers. Strategic procurement allows to lower total costs, higher quality,

better delivery, fewer supplier and outsourcing of non-core operations to the

most reliable suppliers. However, this means that a narrowed supplier base may

result in less bargaining power. In addition, delivery problems should affect

operations and the functional and technical capability of suppliers should

limit the quantities and types of parts that can be purchased.

Already, many manufacturers are seeing order sizes shrink, and

frequency of delivery increase. To meet these customer requirements a company's

suppliers must be similarly aligned to meet the needs of the marketplace and

the customer. In the aerospace and automotive industries, a tier system has

been developed consisting of many levels of suppliers, assemblers and an end

assembler/marketer. Each tier works with its immediate suppliers to operate as

efficiently as possible.

In order to perform its role, a strategic procurement program

requires resources and skilled staff. For instance, the Ford motor

company's encountered a purchasing fiasco in 2002 , Ford lost about 1

million dollars in its stockpile of precious metals because of failed planning

and internal communication. As a matter of fact, the Ford's purchasing group

used the same techniques they had used in buying commodities such as steel and

copper, while Ford's procurement group was stockpiling large amounts of

precious metals. This example illustrates that a strategic procurement is

essential.

Supply chain management goes beyond production and logistics

functions. In order to support the business strategy, it is linked with

planning in coordination with sales and marketing. Several tools such as

Business Planning, Sales and Operating Planning coupled with the use of

information technology enables firms to better plan and manage their

business.

PART I: Supplier Relationship Management, the

extension of supply chain management

Supplier relationships are critical to any organisation. As

they influence product development costs, inventory levels, manufacturing

schedules and the timeliness of delivery of goods and services, Suppliers can

directly impact the financial performance and profitability of a buying

enterprise.

Many leading companies have realized that it is worthwhile

investing to make sure these relationships are managed effectively and

efficiently. In recent years, companies have invested in supply chain

management (SCM) software to automate procurement processes, improve delivery

times and reduce the cost of doing business. Nowadays, market trends, such as

increased global competition, shorter product lifecycles and the outsourcing of

business processes, require organization to improve collaboration with their

supplier base and to examine methods of further reducing the costs associated

with supplier relationships.

Supplier relationship management (SRM)

represents an evolutionary extension of supply chain management, driven by the

need for enterprises to better understand their suppliers' long-term financial

and operational contribution to the top and bottom lines. It also represents an

opportunity to improve the accuracy and speed of buyer-supplier transactions,

while improving collaborative working practices to the benefit of both parties,

driving continuous improvement and lowering total cost of ownership. It is the

next step in managing the supply chain more effectively.

Primarily, SRM tools have been developed to reduce the total

cost of ownership (TCO) for procured goods, while creating competitive

advantage for an organization through deeper relationships with its

suppliers. Another trend that highlights the need for

effective supplier relationship management is the move by enterprises to

outsource key functions, from design to product assembly to after-sales

service, in order to improve competitiveness and financial performance.

It is obvious that procurement represents the single largest

expense for most organizations. Therefore, the development of relationships

with the best suppliers is key to the company success as it ensures timely

delivery, product quality and best prices.

Different mechanisms can be used in order to reduce

procurement costs. For instance, catalogs, auctions and request for proposals

are often put in place to reach that goal. However, if the Customer

Relationship Management systems of each player are not interconnected, not

enough suppliers will respond, catalogs will not be completed of auctions. In

this case, the company cannot achieve the reduction cost expected.

It seems that one of the first concerns of IT initiatives was

the development of supplier relationship through EDI and e-procurement

solutions. To that purpose, EDI and e-procurement solutions help to exchange

data (e.g contract, order, delivery coupons) between customers and suppliers.

However, they do not really tackle the main relationship management supplier

issues such as the understanding of suppliers needs, behavior or performances

measures.

1. The SRM concept:

Supplier Relationship Management is defined as follow by the

Gartner Group: "the practices needed to establish the business rules,

and the understanding needed for interacting with suppliers of products and

services of varied criticality to the profitability of the

enterprise". Other definitions summarize SRM as the next generation of

e-procurement or integrated solution which bridges product, development,

sourcing, supply planning, and procurement across the value chain.

We are going to adopt a marketing approach toward Supplier

Relationship Management, meaning that SRM must attract, filter suppliers, and

promote the company needs. As a matter of fact, SRM needs to support the entire

supplier relationship lifecycle.

SRM must attract new suppliers as in our knowledge and global

economy, it is becoming more and more difficult to find the best supplier. SRM

must also help to acquire new suppliers by doing business with them. As working

with the best suppliers is key to maintain a competitive edge, SRM must help to

retain the best ones. As ending a contract with a "bad" supplier is another

filter, SRM must help to track the rejection of termination of contract

The main goal of SRM is to achieve the better purchase by

supporting and developing the suppliers understanding. Consequently, companies

should gain the following competitive advantages:

- Increase satisfaction of goods and services purchased and

speed up product development by promoting a shared knowledge of suppliers and

alternative technologies.

- Increase supplier's satisfaction to attract and retain the

most competitive ones.

- Lower prices for purchase and maintenance of goods and

services by improving business processes across the supply chain.

Technical integration is another key requirement of SRM

solutions implementation. Software companies often propose the integration of

both supplier's CRM and buyer's SRM. As a matter of fact, this synchronized

integration should develop the relationship and the speed of information

exchange. However, we must keep in mind that prior actions need to be conduct

before that. First of all, the company must find the proper supplier, perform

some check or investigation, and discuss the product specifications. At this

stage of implementation, the SRM solution does not need integration with the

outside. The company needs to collect its internal sources such as procurement,

sales or marketing before calling for information from the outside. As a matter

of fact, in very competitive market, suppliers are often changed and it is very

difficult to keep information up to date.

1.1 The Technical enablers

The basis of any SRM solution is a common supplier repository.

When this repository works, it can be used for reporting, analysis tools.

- Content management and document

management: the documents available can concern products and services.

They can also cover the infrastructure such as building, factory and all the

goods purchased or needing maintenance.

- Knowledge management: As the field knowledge

of a procurement officer is its key asset, the experience sharing can lower

training time. Consequently, it can impact the procurement performance.

- ERP integration: links the existing ERP and

legacy system with the SRM functionalities. Integration is the key element for

a proper SRM

1.2 Customer service and support: SRM support

functionnalities

SRM products support the company relation with its suppliers

in order to provide the best quality and most suited services to its customers

at the lowest cost. That is the reason why SRM helps to collect and manage the

information from all departments. For instance, identified product issues can

be reported by the call management unit, which updates the supplier repository.

The procurement officer is automatically informed and can contact the supplier.

Then the product line can be adapted and the product design modified in order

to solve the problem. With regard to supplier selection, this problem tracking

is highly valuable as the supplier corrective actions will be considered.

.

- Call management:

SRM focus on the calls which are made to suppliers. The

system ensures that a call for information or maintenance is followed until the

end of the process. Call management is not restricted to the purchase officers,

it can be used by every employee of the firm.

- Field service and dispatch:

In the case of maintenance the action of production and

responsible users must be coordinated. That is the reason why the concerned

employee must have granted access to specific information such as warrany,

product specifications...

- E-Service:

Call management, Field service and dispatch can be accessed via

the web and need the appropriate support

1.3 SRM and Purchase:

One of the SRM goal is to achieve the automation of the sales

force, meaning that it must help to improve the efficiency by reducing time and

cost of sales. Electronic catalogues, auctioning and electronic request for

proposals (RFP) were the last evolutions since the 70's. ISRM which,integrates

these tools and the other procurement activities (e. g product design, product

development) imposes itself as the natural evolution.

- Purchase assistant:

It manages bids and assists in the creation of the Request for

Proposal and requirement description.

- Opportunity Management System:

The identification of the company needs is key to the company

activities and that is the reason why they

must be tracked from their

identification to the actual purchase. They can concern product improvements

or

completely new products and services. Consequently, SRM must enable to

prioritize the needs and to track

their moves along the cycle. It can also enable to report the

activities and to manage the workflow in order to automate the paper flow.

- Purchase configuration system:

After the identification of the product or service need,

comes the design, the writing of specifications, the description and the

definition of the actions to be taken such as the financing, the best

combination of suppliers or the estimation of the price

- Partner Relationship Management:

As most of the suppliers depend upon their own suppliers

performances, partner relationship management is key to the success of both

players. That is the reason why providing the right support to your supplier

can increase its performance and consequently reduce your costs. In that

partnership perspective, the smaller companies are enabled to offer joint

products and services through consortiums. Keeping track of relationships with

its own suppliers and its suppliers' suppliers allows to identify problems or

potential improvements. As well as the relationship tracking, the assistance in

planning, recruitment, training, certification, lead management and channel

market help the partner to improve its efficiency and service.

- Interactive purchasing systems:

The definition of standard acceptance criteria and dealing with

standardized goods, allows to automate the purchase decision using an

auctioning process.

1.4 SRM and Marketing:

Marketing is at the center of any sales strategy. To many

purchase officers, the best warranty for a successful purchase is the number of

suppliers in competition. By promoting its needs through the use of marketing

techniques (single, multiple-channel campaigns) a company can attract as many

suppliers as required. Company directories can also be used, but automated

tools to search on the Internet for suppliers are now emerging .

- Campaign management system:

The search for suppliers must be pro active as simply waiting

for the suppliers to come is not efficient. Suppliers also need to be attracted

through the use of communication channels such as electronic publication,

newspaper, newsgroups and marketplaces. It is also necessary to know the cost

of these tracking sources. Furthermore, it is essential to target the best

suppliers.

- Telemarketing: After the identification of potential

suppliers, the purchase officers get in direct contacts with them in order to

collect additional information. The information collected can even lead to the

modification of the needs or product reshaping. Then, these information can be

shared among the employees of the company. The system can also keep track of

contacts.

- Web measurement tools:

Web based purchase system such as auction or RFP must be

measurable. Identification, the users profile and how they use the system must

be known in order to measure the efficiency of the Web based purchase

system.

1.5 Conclusion

The underlying philosophy of SRM system is the better

understanding of the supplier by collecting and aggregating information from

various sources (e. g purchase officer, marketing, R&D, service and

support, maintenance). Consequently, companies are allowed to identify the best

suppliers and therefore help to improve the company performance. From that

internal perspective, SRM should be seen as a complement to the buyer's CRM.

In order to gain maximum profit from Customer Relationship

Management (CRM) and SRM, both systems need to be integrated. As a matter of

fact, customer and supplier's data sources are sometimes the same. In addition,

CRM systems, which collect customer information, also provide data about

supplier's product or service quality. SRM systems collect supplier's customer

information and customer satisfaction studies, which can complement the CRM

systems. Consequently, integration should avoid redundant information and

ensure that the widest range of information sources is covered. We can conclude

that maximization of the information flow can be done though the integration of

both CRM and SRM with the major company information systems such as ERP.

2. Concrete Example: Boeing and the evolution of the

supplier role

2.1 Boeings transformation into a large parts and systems

integrator

Founded in 1916, Boeing evokes images of the amazing products

and services. Each day, more than three million people board Boeing jetliners,

335 satellites put into orbit by Boeing launch vehicles pass overhead, and

6,000 Boeing military aircraft stand guard with air forces of 20 countries and

every branch of the U.S. armed forces. They are the leading aerospace company

in the world and the No. 1 U.S. exporter. Boeing holds more than 6,000 patents,

and their capabilities and related services include advanced information and

communications systems, financial services, defense systems, missiles, rocket

engines, launch systems and satellites.

But the company is about much more than statistics or

products, no matter how awe-inspiring. Boeing's 186,900 employees, with 23,400

advanced degrees, are some of the most highly skilled, educated and motivated

in the world. Partnered with hundreds of thousands more talented people at

15,842 suppliers worldwide, Boeing sees tremendous opportunities in the years

ahead for connecting and protecting people, as well as streamlining their

supplier network to increase profitability and improve efficiency.

Boeing clearly transforms itself into an integrator of large

parts and systems. Consequently, supplier's role is completely changed. In the

past, Boeing and its suppliers were duplicating their efforts in development

and production. For instance, when designing and building equipments, the

Boeing supplier was sending it to its lab or production area. Then, the

supplier was testing and shipping this equipment to Boeing which was repeating

the very same operations.

Nowadays, Lean manufacturing principles rely more heavily on

the supply base in order to achieve customers demand. Consequently, as

suppliers jointly develop systems with Boeing, it avoids redundancies. This

Lean manufacturing approach completely shifts the role of suppliers who are not

vendors but suppliers of Boeing components,which are meeting Boeing

specifications. Lean manufacturing results in reduced cost and better

products.

As Boeing focuses its attention on the integration of large

components and systems and total life cycle support, the role of the supplier

has become even more critical. It means that suppliers are obliged to assume

more and more responsibilities. They must manage everything from raw materials

to critical certifications. They are even requested to assume the management

and oversight of quality and delivery from other suppliers in the chain.

Consequently, it is key to eliminate waste and to optimize supply chains.

For instance, Boeing applies Lean principles to its inventory

management. In order to streamline its production processes, Boeing adopted

just-in-time ordering, point-of-use delivery and internal kitting.

Consequently, Boeing suppliers were required to use just-in-time techniques.

In support of this, Integrated Defense Systems has adopted an

online supply-chain tool called consumption-based ordering. This tool allows

Boeing to share its inventory levels with suppliers. The system lets suppliers

aggregate demand and order at their discretion, building and shipping only when

Boeing inventory levels fall below specified thresholds.

The supplier role shift allows Boeing and its suppliers to set

inventory levels based on consumption rates needed to support production. As a

consequence, Boeing cut the number of storage facilities at its production

sites. Boeing facilities are no more filled with raw materials and inventory.

Boeing receives parts just in time at a given assembly area. The use of eBuy

and the Min/Max ordering system in Wichita, Kan allowed Boeing in a single year

to reduce inventory by more than $300 million.

From the supplier perspective, it is easier and more efficient

to plan the production rates rather than waiting for orders. In addition, they

are enabled to forecast staffing requirements, to better schedule maintenance

and to perform their Lean improvements.

Boeing's focus is on large-scale systems integration, which

must result in total customer solutions and lifetime support. That is the

reason why Boeing suppliers are no longer considered as subordinates but as

team members. Indeed, Suppliers imputs are critical. For instance, Goodrich and

Hamilton Sundstrand are doing more and more systems integration works, which

were usually conducted by Boeing.

In the past, each company was used to hold its strategies and

information. Data and ideas sharing significantly improved communication

between Boeing and its suppliers. It helps both players to improve their own

production systems. For instance, a better communication, processes and

understanding simplifies the testing procedure. The testing procedure, which

should be performed only one time allows lower costs and a better product.

2.2 The 787 Dreamline program: the elevation of suppliers

status from providers to partners

Suppliers on the 787 program are not just being consulted on

how to improve the current systems or components they provide. They are sharing

risk by participating early on in the design-build process to ensure the best

design is used from the start.

Boeing decided to significantly change its supplier

involvement in the 787 program. Instead of simply consulting them, Boeing

required its suppliers to share risks. In order to use the best design,

suppliers actively participate in the design-build process, meaning that they

were involved in the conceptualization, joint development and detailed design.

All the new ideas for systems and structures were considered during the

conceptualization phase. Then, Boeing selected a small number of suppliers for

the

joint development phase. This dozen of suppliers assumed a

greater responsibility than on previous new airplane projects, they became real

partners. For instance, Goodrich collaborated on the development process of the

787 nacelle and thrust reverser system. Usually, such a development process

implies the competition of a large number of people including independent

designers and competitors. The usual development process often leads to design

iterations. Instead of this, Goodrich, Boeing and others designed the 787

nacelle as a team. Then, all team members stepped back and competed normally to

win the contract.

In order to improve its supply chain efficiency, Boeing

heavily reduced its core supply base (79 percent) and increased business with

high-performing suppliers. The number of Boeings suppliers has dropped from

more than 30,000 in 1998 to 6,450 now. These 6,450 suppliers are based in more

than 100 countries. 86 percent of the purchase and change orders transactions

are conducted through eBuy. The system delivers more than 360,000 transactions

a month electronically.

Considering the relationships strengthening and the evolution

of supply chains, prime contractors focus on larger-scale assembly integration.

As they share risk, support the product throughout its life cycle and focus on

innovation and improvement, suppliers are becoming real partners, they are no

more subordinates.

· The new supplier model:

They are many reasons to move to a new supplier model.

Firstly, Procurement costs represent a high percentage of the sum spent on the

aircraft building. Consequently, the money saved in Procurement costs can be

invested in new products and services.

Second of all, better asset use by Boeing and its suppliers

is highly valuable. As a matter of fact, owning and operating facilities, which

works at reduced capacities is completely inefficient and out of sense. That is

the reason why letting the suppliers operate can be the best solution.

Therefore, it allows Boeing to invest in new technologies and its suppliers to

become strong community leaders

Thirdly, it is obvious that working with only the best

suppliers allows to maximize opportunities to consolidate work with them.

Boeing ensures the highest quality and lowest units costs that can be passed

along to the customer.

The shift in the supplier role allows Boeing to move up the

value stream by focusing on the customer voice and requirements, the airplane's

overall design, architecture and integration and then on final assembly and

delivery. Managing an efficient and responsive supplier base allows Boeing to

improve the quality and safety of the products delivered. In addition, these

products are less expensive.

Lean Supply Chain does not only concern manufacturing. It

should be applied to the whole product life cycle from raw materials to the

fleet deployment. This Lean Supply Chain dynamic implies trust between true

partners. It means that Boeing must sometimes transfer a core competency to its

suppliers, which can do it as well as Boeing and even more better. In order to

remain competitive, Boeing depends upon one healthy supply chain indeed. As the

supplier becomes an integral part of the design and production process, Boeing

and its supplier share a common destiny. Boeings success is fundamentally

linked to how well it works with its suppliers.

PART II: E-commerce exchanges

In the late 1999/early 2000, after e-markets encountered

hurdles in gaining traction, the press and investment community refocused on

the emerging consortiums. Analysts and industry experts considered that these

consortia would be "the next big thing" in the B2B landscape. By 2000, private

exchanges overtook consortia in terms of favourable media coverage. Analysts

predicted exponential growth in transaction volume and dollars in current and

near-term investments.

Obviously, we cannot consider that e-commerce exchange is the

perfect solution or a total failure. It seems that the answer lies somewhere in

between and varies from company to company. However, we must keep in main that

e-commerce exchanges offers a wide range of benefits such as streamlining of

the supply chain process, time and costs reduction or new customer

acquisition.

The e-commerce exchanges models have to face various

challenges. As a matter of fact, they have to meet high expectations related to

tight budgets and times frames for demonstrating the return on investment.

Firstly, these exchanges are must be built out on new and fast valuable

technologies. Secondly, in order to leverage the exchange technology, key

members must change the way they do business.

It seems that the best collaborative exchanges are the ones,

which are based on sustainable models. However, financial independency from the

founders can only be gained through the continued support of key members

organizations.

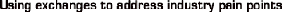

1. The three e-commerce exchange models

1.1 Public e-marketplaces

Often funded by venture capitalist, Public e-market places

are independently owned and develop on-line marketplaces. These neutral

e-marketplaces focus on price discovery and clearing. By listing supply and

demand for specific products and services, they try to create a transparent

market. In addition, the quick identification of trading partners and market

pricing help to reduce the cost of purchasing information gathering. 70 percent

of public e-marketplaces have either ceased operations or modified their

business model.

1.2 Industry-sponsored marketplaces or

consortia

Consortia are jointly developed and owned by several industry

suppliers. The functionalities vary from a broad to a narrow scope. For

instance, it can include supply chain forecasting and replenishment for most

purchases or only product development for a single subsystem. It can also deals

with industry standards. Examples: Covisint for the automotive industry and

Exostar for the aerospace industry;

1.3 Private exchanges (PTXs)

Private exchanges are owned by only one industry player. It

is often used to manage, monitor and therefore optimize value chain processes.

Unlike consortia, in order to participate, PTXs require partners to adapt to or

integrate with the owner's technical applications and/or data management

standards(e.g: Boeing, DaimlerChrysler)

Sixty-five consortia have been formed since January 2000. Of

the 65 consortia that have been formed, 7 have already shut down and 14 have

merged or been acquired. However, the leading players in the consortia space

are gaining traction. Their progress can be measured in terms of infrastructure

development or degree and satisfaction of use. The capital invested, the

employees hired, and functionality developed and brought on-line help to

measure the infrastructure development. The equity members and non-equity

members attraction, the transaction volume, and the use of the applications

also helps to evaluate the success of the consortia. These metrics show the

quantifiable evidence of consortia traction.

2. Industry-sponsored marketplace infrastructure:

2.1 Capital invesment

Capital committed has been under $40 million for some

consortia serving narrow industry segments or with focused functionality.

Investment has totaled $200 million or more at consortia addressing larger

industry segments with functionality addressing several value chain processes

(e.g.Covisint). With regard to the number of employees hired, six consortia out

of nine employ 60 or more full-time staff.

2.2 Participant volume

It seems that the infusion of capital from new industry

investors can be interpreted as a strong sign of industry confidence in a given

consortia. In the past years, 10 consortia gained new equity members in the

past year. In addition, many consortia have increased their base of non-equity

members and participants, or users within member companies.

We must keep in mind that non-equity members are key to the

success of a consortia as they ensure that buyers and suppliers want to use the

exchange. In addition, it is highly valuable to give more breadth in the types

of products and services traded. The transaction volume can rise as well as the

number of trading participants. For instance, Covisint's

member list is over 1,700.

Transaction volume varies from an industrial sector to

another, but at least 15 consortia have transacted over $100 million. Among

these, Covisint has transacted over $150 billion. This volume includes both

indirect products like office supplies and parts that will go directly into end

products. For instance, DaimlerChrysler has procured $3 billion worth of highly

engineered parts for future models via Covisint reverse auctions.

2.3 Industry-sponsored marketplace

functionalities

With regard to functionalities deployment, auction

functionality and on-line catalogs has been launched by many consortia. The

on-line catalogs took more time to bet put in place. As a matter of fact, you

first need to establish product hierarchies, to clean and standardize product

information. Then, you must load hundreds of thousands of stock keeping units

(SKUs) for each catalog. For instance, 200 catalogs have been rolled out by

Covisint.

In addition, tailor made functionalities meeting unique

industry needs has been rolled out by many consortia. These tailor made

functionalities include product development functionality for the auto industry

or spare parts inventory visibility for the airline industry.

Industry-sponsored marketplace functionalities mainly focus on

purchasing applications and on the architecture supporting the cross-enterprise

collaboration. Consequently, most of the consortia provide purchasing tools

such as on-line purchase order generation and routing, reverse auctions,

on-line catalogs, and e-requests for proposal or e-request for

qualification (e-RFx).

In addition, buyer-led consortia provide broader strategic

sourcing services through industry purchasing experts. These purchasing experts

help in the sourcing process from the beginning to the end. It means that they

identify commodities to source, recommend and conduct an auction, an e-RFx or

another sourcing event.

From the buyers perspective, Purchasing tools are creating

value in three main ways. Firstly, catalogs or strategic sourcing service

reduce search costs for suppliers of specific goods. Secondly, on-line purchase

order generation and routing as well as e-RFx reduce the administrative costs

of purchasing goods and services. Thirdly, auctions reduce time to complete

price negotiations.

It seems that the purchasing tools available allow the

leveraging of the aggregated volumeof purchases among multiple buyers. It

allows to improvement of the purchase price. However, some consortia did not

offer this service and privilege single-buyer sourcing events in order to

prevent anti-trust issues.

From the supplier perspective, purchasing tools enable

worldwide access to new buyers and increasing penetration with existing

accounts. As a matter of fact, suppliers noted that they are enabled to win

business from a new client through a consortia auction. Furthermore they often

receive orders from this customer for another part. However, we must keep in

mind that the benefit of increased revenues is frequently offset by reduced

margins on the business won via reverse auctions.

In several industries, suppliers gain access to purchasing

tools as well as the buying tools. For instance, Covisint market its auction

and other purchasing tools to the automotive industry players so that they

reduce their costs through reverse auctions.

From the industry perspective, the value of architecture is

created through shared systems development and management costs such as

portals. It also reduced communications costs such has data and communications

standards. In addition, system integration helps to reduce purchasing and value

chain processes administrative costs.

Some consortia went beyond procurement and architecture

functionality. For instance, Aeroxchange developed a tool,

which allows to share inventory visibility among airline industry players. This

"visible inventory" reduces both administrative costs and the time required to

find parts dedicated to maintenance. Therefore it helps to decrease flight

delays and helps to identify spare parts required for routine repair and

maintenance. With regard to internal inventory, Aeroxchange enhances inventory

management through the reduction of holding and obsolescence costs. In

addition, companies are enabled to sign agreements related to the sharing of

their inventories.

It seems that Industry-sponsored marketplaces development

plans are mainly focused on the key industry pain points. Industry pain points

can be described as the processes, which have significant impact on costs,

quality, or value of the product. As a matter of fact, these specific pain

points should be solved efficiently through industry collaboration.

3. Private exchanges structure and functionalities

3.1 Private exchange structure

While the consortia results and accomplishments are covered,

private exchanges do not reveal such information. However, we can say that at

least 25 percent of the Fortune 100 companies have built, or are building, a

private exchange. In addition, a survey conducted by AMR Research revealed that

the average cost to build a private exchange was of $83 million for Fortune 500

companies. Considering the economic context, this cost should appear as too

huge. However, it must be considered in relation to the breadth and depth of

functionality that these firms are developing.

The private exchange development varies a lot from one

exchange to another as it depends on the type of processes being addressed and

the size of the owner. In addition, some private exchanges are brand new and

others were put in place ten years ago.

Private exchange functionalities have allowed companies to

create an advantaged cost structure while changing the rules of the game in

their industry. It seems that private exchange functionalities are suddenly on

the schedule of both large and small companies.

Large companies are frequently undertaking functionality

addressing several value chain processes. DaimlerChrysler, for example, is

developing tools to address procurement, product development decision support,

and supply chain networking with multiple tiers of its supply chain.

3.2 Private exchange functionality

Obviously, the functionalities provided by private exchanges are

more diverse. Most of the private exchanges build procurement tools or tools

dedicated to other value chain processes.

It seems that the procurement tools developed by private

exchanges are similar to those developed by consortia. Usually, these tools are

eRFx, e-catalogs, auctions or data mining. However, we must keep in mind that

instead of cross-enterprise opportunities, these tools leverage individual

organization opportunities. They usually go beyond the tools put in place at

consortia but the costs are not shared. They vary from one company to another,

they are often dedicated to value chain processes such as product development,

supply chain network integration or sales and marketing

3.3 Private exchange value creation: the DaimlerChrysler

supply chain network example

As the automotive industry supply chain involves hundreds of

suppliers, its management is challenging. The Tier 1 suppliers are the ones who

have direct relationships with the OEMS. The other suppliers have indirect

relationships with the OEMS, they supply products to the OEM through other

suppliers. Consequently, the automotive supply chain can imply four levels or

more of tiers for some subassemblies.

With regard to forecast, suppliers situated at different

levels within the supply chain receive different amounts of forecasted demand

information at different times. For instance, Tier 1 might receive weekly

forecasts with 12 to 15 months of monthly demand information and 5 to 6 weeks

of weekly demand information from DaimlerChrysler. Obviously, this information

is not immediately passed on to lower-tier suppliers.

As the supplier has to deliver its orders on time, he might

hold extra inventory of both raw materials and finished product in order to met

DaimlerChrysler demand fluctuations. This inventory results in higher costs and

implies risk of obsolescence as the customer preferences might change. In

addition, the supplier might schedule overtime and incur incremental equipment

changeover costs due to late changes in the production schedule. In order to

get the product faster, the supplier might also use expedited freight.

DaimlerChrysler's forecast is changed from a number of cars

of specific makes and models, to part numbers and metrics that are meaningful

to each supplier (such as yards of a particular seat fabric). Considering the

supplier situation, DaimlerChrysler worked on the development of a software,

which translates its weekly demand forecasts to the requirements of each

supplier of its supply chain.

This translated forecast data can then be sent out to each

supplier in the company's supply chain at once. Development and implementation

of this supply chain networking functionality has many complexities that must

be overcome before it can be launched to the entire supply chain. To date it

has been piloted with three supply chain segments. However, the opportunity

represented by this functionality could yield a significant savings per car.

Based on this opportunity, DaimlerChrysler continues its development and

piloting efforts in supply chain networking.

4. Choosing between Industry-sponsored marketplace and

private exchange

Even if the tools developed by both consortia and private

exchanges do overlap each over, it is necessary to identify the most

appropriate tools. As a matter of fact, it seems that Consortia are more

appropriate when it is possible to leverage technology costs across companies

in a given industry. In addition, they better suit companies when

cross-enterprise collaboration is needed to capture one given process benefits

such as airline spare parts inventories, collaborative planning or

forecasting.

Private exchanges are more appropriate when the company

benefit from a competitive advantage such as Boeing's product development

functionality. Private exchanges must also be considered when there is no

consortia put in place or when the consortia does offer the desired tools such

as DaimlerChrysler's supply chain networking tool.

4.1 Sustainability of Industry-sponsored marketplaces

and private exchanges

Industry-sponsored marketplaces and private exchanges seem to

be both sustainable. As a matter of fact, consortia and private exchanges have

developed or develop value-creating and customer-ready functionalities.

However, the success of these functionalities greatly depends upon the ability

to gain participants adoption and value demonstration.

Three key factors support the case for the sustainability of

industry-sponsored marketplaces. Firstly, the industry players must consider

that industry-sponsored marketplaces will create functionality vital to the

future of their industry. Secondly, industry-sponsored marketplaces have

learned from the failure of the public e-marketplaces and should not make

similar mistakes. Thirdly, industry-sponsored marketplaces are morphing their

models to respond to market requirements.

Industry-sponsored marketplaces can be considered as cheap as

a group. They usually focus on few key products in order to control technology

costs. They often hire more staff after the implementation of the exchange in

order to gain incremental revenues. The industry and systems expertise

developed combined with close partnerships with customers, results in tailored

made functionalities. Industrysponsored marketplaces learned from the public

marketplaces that they must control the burn rate, create real value while

minimizing the disruption brought about by change.

It seems that two years ago consortia were reduced to

off-line buying groups which only purpose was to aggregate the purchase volume

of several companies and then negotiating better pricing from suppliers. Today,

several consortia, including Covisint, do not aggregate purchasing volume

across.

As consortia main goal is to meet its client requirements,

they did not adopt an inflexible business model, but rather what we can call a

morphing model. As a matter of fact, they are setting the product development

plans, which are meeting their member needs. They also adjust their pricing

models, tailor customer service processes and levels to the requirements of

buyers and suppliers. For instance, Covisint develops and maintains broader

functionality dedicated to several value chain processes which are critical to

the automotive industry.

Even if private exchanges are developed and managed by large

and powerful companies, that does not grant success. As a matter of fact,

private exchanges have to compete for capital, best people and the top

management support. They must also have enough time to demonstrate the return

on investment and value created.

It seems that, development costs of the more complex

functionality should be covered by the savings obtained through the purchasing

functionnality (e.g reduced prices through auctions, reduced administrative

costs from catalogs, automated process flow tools). However, the cost savings

appear in the budgets of the business units purchasing goods while development

costs fall into the e-business organization's cost center. Consequently, it is

still difficult to demonstrate that these savings cover the development costs

of a complex functionality.

In order to survive, private exchanges must create value,

ensures the top management support, partner with business unit managers to

drive internal and external adoption. They must also make sure that they

continue to meet the needs of the business units

In order to justify embarking on an investment in exchange

functionality, either through a consortia or internally through a private

exchange, it is critical to understand the value-creation potential of an

exchange. It is impossible to outline a specific set of instructions for this

assessment, as exchanges vary as much as the companies and/or industries they

serve. We can, however, outline the key issues that must be addressed in such

an analysis.

Understanding of the value-creation potential of an exchange

is key to both consortia and private exchange. Firstly, it is essential to

determine to which processes the exchange should be dedicated. Then, it must be

showed that the exchange addressed the process in the best manner. Secondly,

value metrics must be provided. Thirdly, a comparison must be made between the

value provided and the development and management costs of the exchange. This

demonstration must help to evaluate if the exchange represents a profitable

investment opportunity.

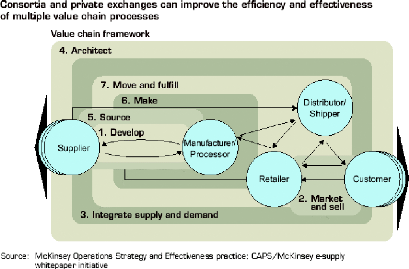

4.2 Identification of the processes to be

addressed

In order to find out the value of an exchange, it is

essential to understand what value chain processes it will address. The above

scheme outlines the value chain processes that exchanges can address. It also

gives a list of the key value chain processes and sub processes that exchanges

may be dedicated to. When the company wants to join one existing consortia, it

is easy to determine if it meets the value chain processes. Indeed, the

consortia provides some existing functionality and a development plan for

future tools.

When creating a consortia or a private exchange, it is

essential to define the processes that should be addressed through the

exchange. At first, purchasing should be considered as it is a key process,

which does not require significant industry customization. As a consequence,

purchasing tools can be chosen quickly and installed. Then, they can generate

savings that can help to fund further exchange development.

Identification of the key industry's key pain points helps to

identify other processes.(see the above scheme). Pain points should be defined

as the process, which significantly impact costs, quality, or product value

from the customer point of view. For instance, Aeroxchange address a key pain

point of the aerospace industry, as the industry holds 55 billion dollars in

inventory. Aeroxchange allows spare parts inventory visibility. It facilitates

the finding of the right part faster for unscheduled maintenance. Thus, it

reduces administrative costs of finding and required inventory levels.

Therefore, airlines are impacted by Aeroxchange as if maintenance is quicker,

the number of delayed and cancelled flights decrease.

When the processes are identified, it is essential to

determine how well the processes can be addressed. We can say that companies

must evaluate the scope of this assessment. First of all, the company needs to

know if the consortia or software address the complete value chain or only

narrow segments of the process. If the consortia or software address only

narrow segments of the process, it is important to know if it addresses the

industry pain points. In fact, few companies provide tools which address all

the aspects of a given supply chain process. However, it does not mean that the

available tools are not valuable. It means that the first stage is to focus on

the most important components of the process and then to build out

functionality over time.