4.2 Comparison of the Classification Techniques

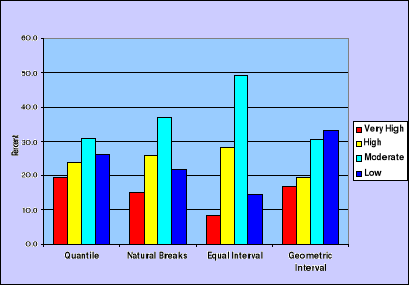

This section presents a comparison of the performance of the

classification methods, namely quantile, natural breaks (Jenks), equal

interval, and geometric interval, in distributing values among risk levels.

Once again to attenuate the effect of the combination schemes, the scores of

each classification were averaged for the 3 approaches. A summary of the

results is displayed in Appendix A, Table 17, while Figure 7 facilitates the

comparison of the distribution of the area among the four risk stages.

Figure 7: Environmental

Health Risks in Port-au-Prince - Percent of area at-risk by classification

technique

Two different patterns are exhibited regarding the distribution

of risk levels. First, whereas the maximum gap among risk levels is very

important for Natural Breaks and Equal Interval (21 and 41%), the Quantile and

the Geometric Interval techniques show a maximum difference of 16%. The second

pattern relates to the cluster of values in opposite categories (low and high).

In this regard, though all the classification techniques have a higher

proportion of values classified as low and moderate risk, equal interval and

geometric interval place a smaller proportion of areas in high and very high

risk (36%) than do Quantile and Natural Breaks (43% and 41%). The former

techniques appear to be pessimistic while the latter is rather optimistic. The

intent of this observation is not to generalize the comparison. This result

might depend on the specific distribution of values and the way these values

were classified beforehand. A visual comparison is offered in Figure 8 and

Figure 9.

For this specific study, if the goal was to highlight the

severity of environmental health risks, the Quantile or the Natural breaks

methods would be appropriate. Conversely, Equal interval or Geometric interval

would be suitable to provide a certain sense of environmental stability and

improvement.

|

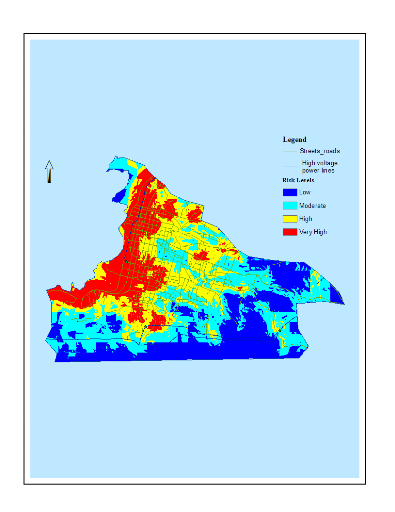

Figure 8: Environmental

Health Risks - Own weighting scheme using the quantile technique: greater

proportion of high/very high risks

|

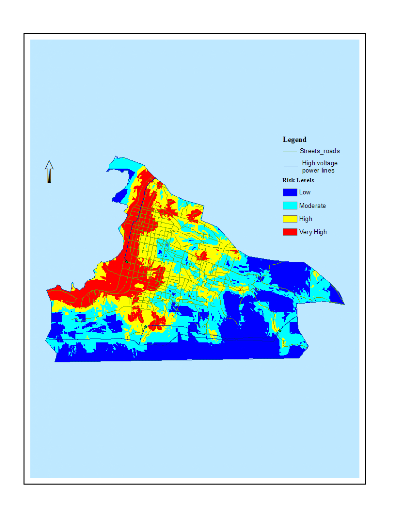

Figure 9: Environmental

Health Risks - Own weighting scheme using the geometric interval technique:

smaller proportion of high/very high risks

|

These discussions and the analysis of the combination schemes

made above illustrate the influence the choice of a specific model or technique

can have on the final results. These results can be manipulated in a certain

way to respond to decision makers' willingness to impress either about assumed

progress accomplished by an implemented project or to attract funding for a

prospective project by drawing a somber cliché of the state of the

environment. As suggested by Osaragi (2002), the selection of a classification

method depends on the nature of data and what we want to communicate about

data.

4.3 Neighborhoods Exposed at High Risks

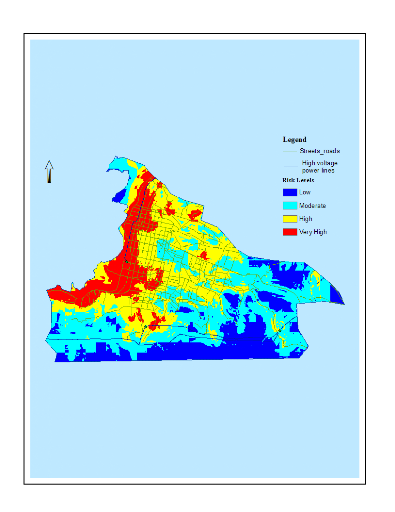

Another important step was to focus on areas identified as highly

prone to environmental health hazards and assess their most salient

characteristics. While we can't display here all the combinations for the

different schemes, only the results obtained with the personalized weighting

scheme coupled with the natural break (chosen randomly) are displayed in Figure

10.

Figure 10: Environmental

Health Risks in Port-au-Prince: Percent of areas at-risk using the Own

weighting scheme and the natural breaks classification method

Twenty two percent (22%) of areas was found overlapped for high

and very high risk from one aggregation method to the other. That is, these

areas always presented high risks irrespective of the approach used to combine

the nine factors. This forms a space of certitude about the results. Most of

these areas are located in the downtown neighborhood and include all the shanty

towns. In particular these areas are well known for high traffic volume, high

population density (so housing density), are located in neighborhoods of public

facilities such as markets, hospitals, cemetery, in low elevation and near

water bodies and the sea coast. These neighborhoods deserve the greatest

attention from the government and/or the non-governmental agencies for

interventions aimed at preventing or lessening impacts on health resulting from

these identified hazards. The complete list of figures is provided in Appendix

B, Figures 21-37. Through these maps the same geographic pattern can be seen

for the different techniques considered. The differentiation, mainly

quantitative, is not substantial.

|