|

JULY, 2019

THE UNIVERSITY OF BAMENDA

|

FACULTY OF HEALTH SCIENCES

|

|

DEPARTMENT OF CLINICAL SCIENCES

|

ETIOLOGIES, CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND

HOSPITAL

OUTCOME OF BACTERIAL MENINGITIS IN CHILDREN

AT THE PEDIATRIC

UNIT OF THE YAOUNDE -GYNECO -

OBSTETRIC AND PEDIATRIC HOSPITAL

A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Clinical

Sciences in the Faculty of Health

Sciences in partial fulfilment of the

requirements for the award of a Postgraduate

Diploma (DM) in Clinical

Sciences.

By

MAURANE EMMA NDJOCK MBEA

Registration

Number: UBa12H034

SUPERVISOR CO-SUPERVISOR

Prof. CHIABI ANDREAS Prof. ATANGA MARY

(c) Copyright by Maurane Emma Ndjock Mbea, 2019

All Rights Reserved

1

DECLARATION

I, Nlaurane Emma Ndjock Mbea, Registration N° UBaI2HO34,

Department of Clinical Sciences in the Faculty of Health Sciences, University

of Bamenda, hereby declare that, this work titled: "Etiologies, Clinical

Presentation And Hospital Outcome Of Bacterial Meningitis In Children At The

Pediatric Unit Of The Yaounde --Gyneco -- Obstetric And Pediatric Hospital" is

my original work. It has not been presented in any application for a degree or

any academic pursuit. 1 have sincerely acknowledged all borrowed ideas

nationally and internationally through citations.

|

Date 4 (t'A f q-cac)

|

|

|

|

|

Signature ~~ j

|

ii

iii

DEDICATION

TO MY PARENTS

CHANTAL

BAYEGUI Epse NDJOCK MBEA

AND

EMMANUEL NDJOCK MBEA

TO MY

SISTER

FINKE FICTIME YAN NDJOCK MBEA

iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I am most grateful to:

Thesis supervisor Prof CHIABI Andreas for his

outstanding teaching received during the course of the work. Professor, your

rigor and constant devotion for a work perfectly done forces our admiration.

Thesis co directors Prof NGUEFACK Seraphin

and Prof ATANGA Mary for their acceptance given to us

in agreeing to guide us in this work. Thank you once more for your availability

and dynamism.

Dean of the Faculty of Health Sciences of the

University of Bamenda for her constant advice and support given to us at any

given circumstances to all her students.

Pediatric Department of YGOPH for their

welcome and help during our study.

Formal Dean of the Faculty of Health Sciences

for his rigorous training he has given to us.

My parents Mr and Mrs Ndjock Mbea for their

love, moral and financial support they have been given me throughout the

realization of this work.

My family members: Mrs Finke Fictime Marie Louise

for her moral and financial support, my sisters Finke yan

and Bayegui Marie Louise for their prayers and moral

support.

Second batch of Faculty of Health Sciences of

the University of Bamenda and my friend Ngo Linwa Esther for

the exceptional 7 years they have made me gone through, together in struggle

and brighter days, thanks.

To all whose names are not cited, I say my most gratitude

towards any form of help from you, thanks.

GOD Almighty for the inspiration, mental and

physical strength and protection he gave me to be able to go through this work

successfully.

v

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION AND OBJECTIVES:

Meningitis is a term that describes the inflammation of

membranes (meninges) and/or cerebrospinal fluid that surrounds and protects the

brain and spinal cord. Bacterial meningitis remains a serious global health

problem, with World Health Organization estimating over 1.2 million of cases

worldwide each year. It still affects mostly children with significant

morbidity and mortality despite the presence of vaccins. Many studies have been

conducted out of Africa, in Africa and in Cameroon with an incidence of 1.54 in

2014, all emphasizing the continuous rising incidence, thus our main aim being

to: determine incidence, etiologies, clinical presentations, and describe the

hospital outcome of bacterial meningitis in children.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This was a retrospective cross sectional descriptive study

done at the pediatric unit of the Yaoundé Gyneco-Obstetric and Pediatric

hospital. Those included in the study were children admitted for meningitis

from the 1st of January 2014 till the 31st of December

2018 and aged from 1 month to 15 years. The sample size of 23 was calculated

from the Cochrane's formula, and there was consecutive search of files in the

archives for the following information: pathogens isolated and clinical

manifestation and hospital outcome of children with the disease. The data were

recorded using CS PRO 7.2(census and survey processing system) soft ware and

analysed using IBM SPSS 23.0(statistical package for the social sciences)

RESULTS:

The incidence of bacterial meningitis in children at the

Yaoundé Gyneco -Obstetric Hospital was 0.3% and the female sex was

predominant at 56% in the admissions. Streptococcus pneumoniae and

Neisseria meningitidis were the most common pathogens isolated; 63%

and 25% respectively. Children within the age group of < 12 months were the

most affected. Fever (95.3 %) and convulsion (60.5%) were the most common

presentations of meningitis at time of admission, while neck stiffness and

meningeal signs (Kerning and Brudzinski's signs) were present on clinical

examination at 20.9% and16.3% respectively. A mortality rate of 2.4% was

recorded against cure rate of 97.6%.

vi

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION:

The incidence of bacterial meningitis was 0.3% with

streptococcus pneumoniae being the most common pathogen identified,

and fever and convulsion as the most common presentations of meningitis. Neck

stiffness and meningeal signs were the most common signs on clinical

examination. There was a low mortality rate of 2.4 %.

Following our conclusions ,the ministry of public health is

recommended to look into vaccination campaigns in children all over the country

against infectious diseases especially meningitis. This could be done through

re-enforcement of information, education and communication of vaccination in

children.

vii

RESUME

INTRODUCTION ET OBJECTIFS:

La méningite est un terme qui décrit

l'inflammation des meninges et /ou le liquide céphalo-rachidien qui

entoure et protège le cerveau et la moelle épinière. La

méningite bactérienne reste un problème de santé

publique sérieuse, avec l'Organisation Mondiale de la Santé

l'estimant à plus de 1,2 million de cas dans le monde entier chaque

année. Elle affecte toujours les enfants, avec une morbidité et

une mortalité significative malgré la présence des

vaccins. Plusieurs études ont été faites hors d'Afrique,

en Afrique en général et au Cameroun avec une incidence à

1,54 en 2014, toutes mettant l'accent sur la monté des incidences

d'où le but de cette étude qui et de : déterminer

l'incidence, les étiologies, la présentation clinique, et le

devenir hospitalier de la méningite bactérienne chez les

enfants.

METHODOLOGIE:

Cette étude était

rétrospective-descriptive et a été faite à

l'Hôpital Gynéco-Obstétrique et Pédiatrique de

Yaoundé. Ceux inclus dans l'étude étaient les enfants

admis pour la méningite du 1er Janvier 2014 au 31

Décembre 2018 et âgés de 1 mois à 15 ans. La taille

d'échantillon était de 23 a partir de la formule de Cochrane et

y'avait une fouille consécutive de dossiers aux archives pour recueillir

les informations suivantes : germes isolées, présentation

clinique et devenir hospitalier chez l'enfant atteint de la maladie. Les

données ont été saisis a l'aide du logiciel CS PRO 7 .2 et

analysées avec le logiciel IBM SPSS 23.0

RESULTATS:

L'incidence de la méningite bactérienne

était de 0.3% à l'Hôpital Gynéco-Obstétrique

et Pédiatrique de Yaoundé avec une prédominance de genre

féminin à 56% à l'hospitalisation. Streprococcus

pneumoniae et Neisseria meningitidis étaient les germes

les plus isolés à 63 % et 25 % respectivement .Les enfants

âgés de < 12 mois étaient les plus affectés. La

fièvre et la convulsion étaient des présentations les plus

communes a la consultation, pendant que la raideur de la nuque (20.9%) et les

signes méningés(Signes de Kerning et de Brudzinski) (16.3%)

étaient les plus retrouvés comme signes à l'examen

clinique. Un taux de 2.4 % de mortalité était enregistré

contre un taux de 97.6% de guérison.

viii

CONCLUSION ET RECOMMANDATION:

L'incidence de la méningite était de 0.3 % avec

le Streptococcocus pneumoniae comme germe le plus isolé et la

fièvre et la convulsion étaient les présentations les plus

communes de la méningite. La raideur de la nuque et les signes

méninges comme signes les plus communs à l'examen clinique. Il

y'avait un taux bas de mortalité à 2.4%

Compte tenue de ces conclusions, le ministère de la

santé publique est recommandé de mettre un regard sur les

campagnes de vaccination des enfants dans tout l'étendu du territoire

contre les maladies infectieuses surtout sur la méningite. Le

renforcement de l'information, l'éducation et la communication des

vaccinations chez les enfants est nécessaire.

ix

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DECLARATION i

CERTIFICATION ii

DEDICATION iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT iv

ABSTRACT v

RESUME vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS ix

LIST OF TABLES xii

LIST OF FIGURES xiii

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND SYMBOLS xiv

HIPPOCRATIC OATH xx

CHAPITRE ONE 1

INTRODUCTION 1

I.1) Background 1

I.2) Rationale And Justification 2

I.3 ) Main Objectives 2

I .3.1) Specific Objectives 2

I.5) Research Question 3

I.6 Conceptual Framework 3

CHAPTER TWO 4

LITERATURE REVIEW 4

Ii.1) General Overview 4

Ii.4) Pathophysiology Of Bacterial Meningitis 12

Ii.4.1) Bacterial Invasion 12

Ii.4.2) Inflammatory Response 14

Ii.4.3) Raised Intracranial Pressure 14

Ii.4.4) Neuronal Damage 15

Ii.5) Diagnosis Of Meningitis In Children 16

Ii.5.1) Clinical Diagnosis Of Meningitis In Children 16

Ii.5.2) Paraclinical Diagnosis Of Bacterial Meningitis 17

Ii.5.2.1) Lumbar Pucture And Csf Analysis 17

Ii.5.2.2) Complications Of Lumbar Puncture 19

Ii.5.3) Other Laboratory Investigations 19

Ii.6)

x

Current Treatment On Bacterial Meningitis In Children 21

Ii.6.1) Antibiotic Treatment 21

Ii.6.2) Adjuvant Therapy And Supportive Therapy 22

Ii.6.3) Fluid Restriction 22

Ii.7.2) Chemoprophylaxis 24

Ii.7) Complications Of Bacterial Meningitis In Children 24

Ii.8) Publications On Meningitis 26

CHAPTER THREE 29

MATERIALS AND METHODS 29

Iii.1) Study Design 29

Iii.2) Duration Of The Study 29

Iii.3) Study Setting 29

Iii.4) Sampling 29

Iii.5) Study Population 29

Iii.5.1) Inclusion Criteria 29

Iii.5.2) Exclusion Criteria 30

Iii.6) Sample Size 30

Iii.7) Materials 30

Iii.8) Methods 31

Iii.8.1) Administrative Authorizations And Ethical Clearance

31

Iii.8.2) Patient Recruitment 31

Iii.8.3) Data Management 33

Iii.8.3.1) Ethical Considerations 33

Iii.9.1) Human Resources 33

CHAPITRE FOUR 34

RESULTS 34

Iv.1) Incidence 34

Iv.2.3) Type Of Admissions 35

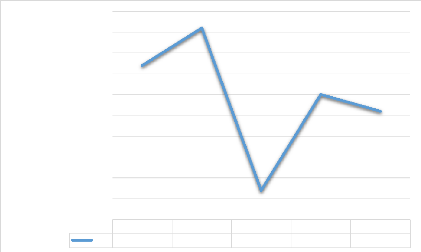

V.2.4) Distribution Of Patients According To Year Of Admission

36

Iv.3) Clinical Presentation Of Bacterial Meningitis 37

Iv.5) Etiologies Of Bacterial Meningitis 41

xi

CHAPITRE FIVE 47

DISCUSSION 47

V.1) Incidence 47

V.2) Clinical Presentation Of Patients 48

V.3) Hospital Outcome Of Bacterial Meningitis In Children

50

Conclusion 51

Recommendations 51

REFERENCES 53

APPENDICES

xii

LIST OF TABLES

Table I: Distribution of patients according

to gender 35

Table 2: Distribution of clinical

presentation according to symptoms. 37

Table 3: Distribution of neurological

clinical presentation according to signs 38

Table 4: Biochemical and cytological aspect

of csf analysis of patients at admission 39

Table 5: Biochemical and cytologic aspect of

csf analysis of patients at admission 40

Table 6: Distribution of pathogens according

to age 42

Table 7: Distribution of complications found

during admission 43

Table 8: Distribution of patients according

to outcome during admission 44

Table 9: Distribution of patients according

to sequelae at time of discharge 45

Table 10: Distribution of patients according

to treatment recieved for sequalae 46

xiii

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: Meningitis Belt in West Africa [14]

4

Figure 2: Countries trained to conduct

surveillance for the Pediatric Bacterial Meningitis Surveillance Network, by

performance level* --- World Health

Organization African Region, 2008 [16] 5

Figure 3:

Causes of confirmed bacterial meningitis from eleven years of

active

surveillance in a Mexican hospital, 2005 -2016. [18] 6

Figure 4 : Pathogenesis of bacterial meningitis

[38] 15

Figure 5: Lumbar spine anatomy[41]. 17

Figure 6 : Distribution of patients according to

age groups 34

Figure 7: Distribution of patients according to

the type of admission. 35

Figure 8: Flow chart illustrating the incidence

per year at YGOPH. 36

xiv

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND SYMBOLS

C D14 : Cluster of differentiation 14

CbpA : Choline binding protein A

CSF : Cerebro spinal fluid

E.coli : Escherichia coli

H.influenzae : Haemophilus influenzae

Hib : Haemophilus influenzae type b

Ibe A : Invasion of brain endothelium protein

A

Ibe B : Invasion of brain endothelium

protein

N.meningitidis : Neisseria meningitidis

OmpA : Outer membrane protein A

S .pneumoniae : Streptococcus pneumoniae

SDG : Sustainable development Goal

WHO : World's Health Organisation

YGOPH : Yaoundé-Gynaeco-Obstetric and

Pediatric Hospital

xvi

THE ADMINISTRATIVE STAFF OF THE UNIVERSITY OF

BAMENDA

Prof Sammy Beban Chumbaw Pro-Chancellor

Prof Theresia Akenji Vice-Chancellor

Prof Suh Cheo Emmanuel Deputy Vice-Chancellor in

charge of Teaching,

Professionalization and

Development of Information

and Communication

Technologies

Prof Agwara Moise Ondoh Deputy Vice-Chancellor in

charge of Internal Control and Evaluation

Prof Roselyn Jua Deputy Vice-Chancellor in

charge of Research,

Cooperation and relationship with the

Business world

Prof Banlilon Victor Tani Registrar

Prof Ghogomu Julius Numbonui Director of Academic Affairs

Dr Mbifi Richard Director of Administrative

Affairs

Prof Anong Damian Nota Director Students' Affairs

MrGiyohYerima Peter Director of Finance

MmeBongnda Winifred B. Beriliy Director of Library

xvii

THE ADMINISTRATIVE AND TEACHING STAFF OF THE FACULTY OF

HEALTH SCIENCES (FHS), THE UNIVERSITY OF BAMENDA

2018/2019 Academic Year

1. Administrative staff

Prof Dora Mbanya Dean

Prof Christopher TangnyinPisoh Vice-Dean in charge of Academic

Affairs

Prof Helen KuokuoKimbi Vice-Dean in charge of Admissions

and

Records

Prof Henri Lucien F.Kamga Vice-Dean in charge of Research

and Cooperation

MrJacobTitafanVoma Faculty Officer

Dr Gerald Ngo Teke Chief of service,programmes,

Teaching

And research

Dr Moses Samje Chief of Service, Administration

and

Personnel

Mr Zaccheus Aweneg Chief of Service, Finance

Mr Humphrey Njoamomoh Chief of Service, Admissions and

Records

Mr Leonard Peyechu Chief of Service, Materials And

Maintenance

Dr Mary Garba Chief of Service, Internships

xviii

Mr Cyprien Bongwong Stores Accountant

2. Heads of Departments

Prof Frederic Agem kechia Biomedical Sciences

Prof Christopher Tangnyin Pisoh Clinical Sciences

Prof Bih Suh Mary Atanga Nursing/Midwifery

Dr Esther Etengeneng Agbor Medical Laboratory

Sciences

Teaching staff

a) Professors

1.

|

Christopher Kuaban

|

Internal Medicine/Chest Medicine

|

2.

|

Helen Kuokuo kimbi

|

Medical Parasitology

|

3.

|

|

Dora Mbanya

|

Haematology

|

|

b) AssociateProfessors

1.

|

BihSuh Mary Atanga

|

Nursing/Midwifery

|

2.

|

Henri Lucien F. Kamga

|

Medical Parasitology

|

3.

|

Frederic Agem Kechia

|

Medical Mycology

|

4.

|

|

Christopher Tangnyin Pisoh

|

General Surgery

|

|

c) Senior Lecturers

1.

|

Esther EtengenengAgbor

|

Nutritional Biochemistry

|

2.

|

Marie Ebob Bissong

|

Medical Microbiology

|

3.

|

Flore Ngoufo Nguemaim

|

Medical Parasitology

|

4.

|

Gerald Ngo Teke

|

Pharmacology

|

5.

|

|

Omarine Nfor Njimanted

|

Medical Parasitology

|

|

6.

xix

Moses Samje Biochemistry

7. William AkoTakang Obstetrics/Gynaecology

d) Assistant Lecturer

Jacob TitafanVoma Physics

e) Instructors

1. Kwende Odelia Nursing

2. Foba Marcelline Nursing

xx

HIPPOCRATIC OATH

« I solemnly pledge to dedicate my life to the service of

humanity;

The health and well being of my patient will be my first

consideration ;

I will respect the automomy and dignity of my patient ; I will

maintain the utmost respect for human life ;

I will not permit considerations of age , disease or

disability , creed , ethnic origin , gender , nationality , political

affiliation , race , sexual orientation , social standing , or any factor to

intervene between my duty and my patient ;

I will respect the secrets that are confided in me , even

after the patient has died ;

I will practise my profession with conscience and dignity and

in accordance with good medical practice ;

I will foster the honour and noble traditions of the medical

profession ;

I will give to my teachers , colleagues , and students the

respect and gratitude that is their due ;

I will share my medical knowlegde for the benefit of the

patient and the advancement of health care ;

I will attend to my own health , well being ,and abilities in

order to provide care of the highest standard ;

I will not use my medical knowledge to violate human rights

and civil liberties, even under threat ;

I make these pomises solemnly , freely , and upon my honour.

»

1

CHAPITRE ONE

INTRODUCTION

I.1) BACKGROUND

Bacterial meningitis is an infectious disease characterized by

infection and inflammation of the meninges due to the penetration and

multiplication of the bacterium in the cerebrospinal fluid. It results in

significant morbidity and mortality globally [1][2], and is

estimated to be fatal in 50% of cases with affecting approximately 1.2 million

people each year with two thirds occurring under 5 years of age

[2].

In USA, bacterial meningitis was responsible for an estimated

4100 cases and 500 deaths annually between 2003 and 2007, while in 2012, in

Africa World Health Organization identified 22000 meningitis cases in 14

countries in the meningitis belt [1][ 3].

Meningitis can be difficult to diagnose clinically

particularly in young infants who do not seem to reliably display the classic

features of the disease [4], where symptoms observed vary from

the bulging fontanel in neonates to frank meningeal signs in older children,

thus high index of suspicion is needed [5].Sequelae vary based

primarily on the etiologic agent [6] where higher mortality

rates tend to be associated with Haemophilus influenza type b

meningitis, pneumococcal meningitis and meningococcal meningitis

[7].

The different etiologies of bacterial meningitis in children

were observed in various studies where Anouk et al demonstrated in 2018 that in

Northern America Streptococcus pneumoniae was the most common pathogen

with weighted mean 43.1% [1].

Touré et al also showed in 2017 in Ivory Coast in a

study that Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis

were the commonest incriminated pathogens [8]. In

Cameroon in a study in 2014, it was seen that the incidence of bacterial

meningitis still remained high despite the introduction of vaccins against the

three most incriminated bacteria, notably Haemophilus influenzae which

was the most common pathogens constituting 39.2%, followed Streptococcus

pneumoniae with 31.6% and Neisseria meningitidis 10.5%

[3].

2

I.2) RATIONALE AND JUSTIFICATION

Bacterial meningitis is a serious often disabling and fatal

infection which causes 170,000 deaths worldwide each year [5].

On a review on meningococcal meningitis particularly, it was

demonstrated that the rate of 15 cases per 100,000 per week for two weeks

provokes vaccination of children aged greater than 2 years with one injection

of group A and C polysaccharide. Even still only about 50 % of cases of

meningitis are preventable[9].

Despite the development of vaccines, ad useful tools of rapid

identification of pathogens and potential antibiotherapy, bacterial meningitis

still remains a significant cause of preventable childhood deaths and a major

cause of neurological deficits and physical handicaps in children [5][

10], especially in sub-Saharan Africa where populations seem to be

more exposed to the different causative agents than any other part of the

world.

Though many reviews, above 100, have been conducted on

bacterial meningitis, especially in Cameroon, we can agree from those reviews

that this disease still makes one to ask question on the control and prevention

of the disease, through the implementation and correct dispensing of the three

main vaccins against the three major causative agents which are;Haemophilus

influenzae typeb ,Neisseria meningitidis and Streptococcus

pneumoniae.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is in line with the goal

3.2 of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) which has as objective to ensure by

2030 a decrease, of avoidable death of newborns and children of less than 5

years [11], to determine the new incidence, etiologic agents,

clinical manifestations and hospital outcome of bacterial meningitis in

children.

I.3 ) MAIN OBJECTIVES

To identify the common pathogens responsible for bacterial

meningitis and to describe the hospital outcome in children with bacterial

meningitis.

I .3.1) SPECIFIC OBJECTIVES

1) To determine the incidence of bacterial meningitis in

children in the pediatric unit at the YGOPH.

2) To identify the common pathogens responsible for bacterial

meningitis in children at YGOPH.

3) To describe the different clinical manifestations of

bacterial meningitis in children at YGOPH and the evolution.

4) To describe the hospital outcome in children with bacterial

meningitis I.5) RESEARCH QUESTION

1) What are the incidence, etiologies, clinical presentation and

hospital outcome of bacterial meningitis in children at the YGOPH?

I.6 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Sociodemograp hic

Characteristics

- Age

- Gender

- Vaccinati

on status - Immune

status

BACTERIAL VIRAL

ETIOLOGIES

-S. pneumoniae

-N.meningitidis

-H.influenzae

CHILDHOOD MENINGITIS

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

TREATMENT

HOSPITAL OUTCOME

? Mortalit y

? Cure

? Disabilit y

3

4

CHAPTER TWO

LITERATURE REVIEW

II.1) GENERAL OVERVIEW

The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes Neisseria

meningitidis, in most countries to be the leading cause of meningitis and

fulminant septicemia and is also recognized to be a significant public health

problem [12] However, large recurring epidemics affect an

extensive region of sub-Saharan Africa known as the « THE MENINGITIS BELT

» (Figure 1) which comprises of 26 countries from Senegal in the West to

Ethiopia in the East [13].

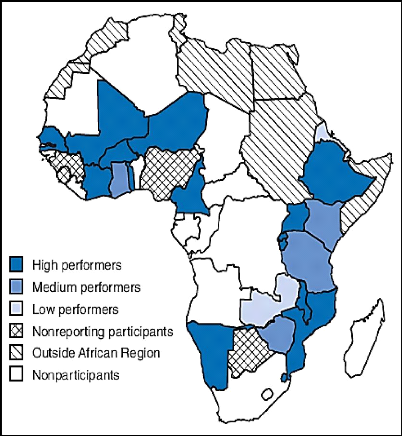

Figure 1: Meningitis Belt in West Africa [14]

Most meningitis cases and out breaks in the African meningitis

belt occur during the epidemic season which tend to extend from November to

June depending on the region [13], with sub-Saharan region

having the world's greatest disease burdens of Haemophilus influenzae

type b streptococcus pneumoniae, and Neisseria meningitides

[15]. An enhanced meningitis surveillance regional

network is also available where the 23 countries participating (Figure 2)

reported in 2017 a total of 29827 of suspected cases of meningitis including

2276 deaths [13]. This was said to represent an increased

5

number of cases compared with 2016 of 18178 suspected cases

resulting also in an increased number of epidemic districts from 42 in 2016 to

57 in 2017[13]

Figure 2: Countries trained to conduct surveillance

for the Pediatric Bacterial Meningitis Surveillance Network, by performance

level* --- World Health Organization African Region, 2008 [16]

6

II.2) ETIOLOGIES AND RISK FACTORS OF BACTERIAL

MENINGITIS IN CHILDREN

In 2000, Hib and S. pneumoniae infections are

accountered for approximately 500,000 deaths in the sub-Saharan region.N.

meningitidis has been responsible for recurring epidemics resulting in

700,000 cases of meningitis [17]

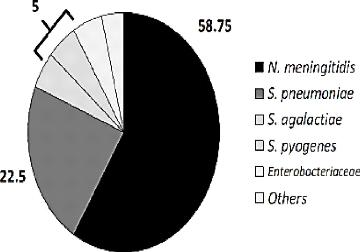

Figure 3: Causes of confirmed bacterial meningitis

from eleven years of active surveillance in a Mexican hospital, 2005 -2016.

[18]

? STREPTOCOCCUS PNEUMONIAE

Streptococcus pneumoniae is one of the main causing

agents responsible for meningitis in newborns, in young children and teenagers

with higher rates of lethality and morbidity [19] [20].

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a Gram - positive, encapsulated bacterium

often found as a normal commensal in the nasopharynx of healthy children

[20].Streptococcus pneumoniae was the commonest cause of

bacterial meningitis in US and Europe, and tends to occur mostly among children

older than 5 years of age [10]. However, the highest risk of

bacterial meningitis caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae

7

is in children greater than 2 years [21]. The

bacterium can become pathogenic, with invasive disease, greatest in patients

who develop meningitis.

? VIRULENCE FACTOR AND PATHOGENESIS

The bacterium is spread by the respiratory fluids from the

infected person when they cough or sneeze, the bacterium then finds its way in

the system where it escapes to the local host defenses and phagocytic

mechanisms, then penetrates the CSF either through choroid plexus /

subarachnoid space originating from bacteremia or via direct extension from

local respiratory system infections [20]. It is able to escape

into the central nervous system easily with the aid of pneumococcal proteins

which include [22]:

> Pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA)

:It is located in the cell wall of the bacterium and acts as a

protective antigen against the host complement system.[22]

> Hyaluronate lyase (Hyl) :This enzyme

mediates facilitation of tissue invasion by breaking down the extracellular

matrix component of the host cell ,thereby increasing tissue permeability.This

factor aids in the pathogenesis of wound infection, meningitis and even

pneumonia[22].

> Autolysin (LytA) :These enzymes are

located in the cell envelope and has a very important role in cell wall

degradation which leads to cell death .They degrade the peptidoglycan backbone

of bacterial organisms , which leads to cell lysis[22].

> Pneumococcal surface antigen A (PsaA) :

This protein is thought to have protective properties and is anchored

to S.pneumoniae through bacterial cell membrane[22].

> Choline binding protein A (CbpA) : It

serves as an anchoring device to pneumococci lipoteichoic C acid structures

present on the surface of the bacterium.Thus aids in the adherence and host

tissue colonization[22].

> Neuraminidase: They enhance colonization

due to their action on gylcans where , they cleave terminal sialic acid from

cell surface gylcans such as mucin, glycolipids and glycoproteins which is

probably responsible for damage to host cell gylcan[22].

Children with basilar skull fractures with CSF leak, asplenism

and HIV infection are at particular risk of developing pneumococcal meningitis

[23], pneumococcal conjugate vaccines have been implemented in

many countries, and immunization with the heptavalent pneumococcal vaccins PCV7

has decreased incidence by incriminating

8

pathogen by greater than 90% [24]. Meanwhile

pneumococcal population undergoes temporal changes in clonal distributions in

the absence of pressure from a vaccine [24].

? HAEMOPHILUS INFLUENZAE

Haemophilus influenzae is Gram-negative coccobacilli

capable of causing serious invasive disease in the child of less than 5 years

of age (Figure 3). Haemophilus influenzae encapsulated serotypes are:

a, b, c, d, e, and f which facilitates its penetration in the blood with the

serotype b being the most virulent of all. The pathogen does not stay alive for

a long time in the environment, it thus has a 12 hours' survival on plastic

objects [25].Haemophilus influenzae type b was the

most common cause of life threatening infection in children in industrialized

countries until universal immunization, where children of less than 5 year of

age, were the primary host with 39% of nasopharynx colonization, but nowadays,

it is instead older children and adults that are considered to be more

susceptible carriers shifting them to primary host[26][25].

? VIRULENCE FACTOR AND PATHOGENESIS

The transmission of the pathogen is done through droplets from

the respiratory airways, through cough, sneezing, speaking from colonized

person, through saliva, and contaminated objects from respiratory secretions.

Sodium hypochlorite at 1%, ethanol at 70%, formaldehyde, glutaraldehyde has

good efficacy against Haemophilus influenzae

[25].However Hib , though not known to produce toxins, it

has the capacity to invade the host system using the following defense

methods[27] :

? Polysaccharide capsule : It is a very

important virulence factor of encapsulated strains of Haemophilus influenza

strains and it protects the bacterium from host immune functions[27].

? Lipooligosaccaharide (LOS) : A major

component of the outer leaflet of the Gram -negative bacteria outer membrane ,

which mediates interactions between bacteria and the host immune system[27].

Hib apart from using the above defense mechanism also uses ,

particular processes to escape from complement systems such as;

- Phase variation which is a immune evasion strategy during

infection where the outer surface of the bacterium is modified to adapt to

changes in the host environment[27].

9

- Binding of host complement regulatory factors which is

important during colonization and infaction, where these factors block activity

at various step of the complement pathway[27].

Globally, Hib accounts for approxi mately 8-13 million serious

illness annually, including 173.000 cases of meningitis causing 78.000 deaths

[28]. The incidence of bacterial meningitis due to the

pathogen has been experiencing a drop in its incidence in developed

countries[8], in Belgium it was at 0,04/100,000 inhabitants in

2012 and even in developing countries where there is implementation of the

vaccin against the Haemophilus influenza type b, less prevalence was

noticed compare to previous years[25]. Despite its reduction

in the cause of meningitis, its identification and prompt treatment are

essential because of the short incubation period which is 2 - 4 days

[25].World Health Organization recommended the addition of Hib

vaccine to immunization programs , according to national capacities and

priorities, however, uptake in developing countries has remained

slow[26].This is partly due to the uncertainty about the true

disease burden[26].

? NEISSERIA MENINGITIDIS

Meningococcal infections occur worldwide as endemic

disease(Figure 3)[29], and it appears that the occurrence of

invasive meningococcal disease is not solely determined by the introduction of

a new virulent bacterial strain but also by other risk factors determining the

transmission of the pathogens [29][19]. Meningococcal

meningitis occurs when Neisseria meningitidis multiplies on the

meninges and in the CSF [30]. Early recognition of this type

of meningitis is important than in any of the acute infectious diseases

[31].

Neisseria meningitidis is a Gram -negative diplococci

which has 13 serogroups defined by specific polysaccharide designated A, B,C,H,

I, K, L, M,X,Y,Z, 29E, and W135(serogroup D is no longer recognized),but is A,

B,C, W135, X, and Y account for most disease where group A is mostly found in

Sub-Saharan Africa, group B found in the temperate climates and group C occurs

mostly as outbreaks [29][32].

Neisseria meningitidis is found in the oropharynx of

10 % of the population with an annual number of invasive disease cases

worldwide estimated to be atleast 1,2 million with 135,000 deaths related to

invasive meningococcal disease and WHO categorizes countries by risk of

meningococcal disease as follows [32];

10

? High risk: countries with greater than 10 cases /100,000 and

/or =1 epidemic Over last 20 years

? Moderate risk: Countries with 2-10 cases /100,000 population

per year

? Low risk: Countries with less than 2 cases /100.000 populations

per year.

The proportion of cases caused by each serogroup varies by age

group also geographic distribution and epidemic potential differ according to

serogroup.Neisseria meningitidis ends to be present particularly in

children less than 5 years old with estimated 500,000 cases and 50,000 deaths

globally each year [29].The largest burden of meningococcal

disease occurs in the sub-Saharan Africa during dry season with the presence of

dust , winds , cold nights with the upper respiratory tract infections combine

to damage the nasopharyngeal mucosa increasing the risk of the disease which is

transmitted through droplets of respiratory secretions while Invasive disease

developing in a small percentage of carriers is regarded as

emergency[32][33].

? VIRULENCE FACTOR AND PATHOGENESIS

Neisseria meningitidis is a fastidious, encapsulated

aerobic bacterium that colonises host mucosal surface using multiple factors

such as[34] :

> Capsule : It is present in strains that

cause invasive disease ,since it provides resistance to antibody and complement

-mediated killing and inhibits phagocytosis[34].

> Lipolysaccharide (LPS) : Induces the

release of chemokines , reactive oxygen speies and nitric oxide and has a role

in resistnce to other host defense[34].

> Adhesins pili : Initiate binding to

epithelial cells,and facilitate passage through the epithelial mucus layer and

movement over the epithelial surfaces .They also facilitates the uptake of DNA

by meningococci and enable adherence to endothelial cells and

erythrocytes[34].

> Opacity proteins : Opa and Opc (only

expressed in Neisseria meningitidis) while Opa is expressed by both

meningococci and gonococci.They have potential roles in pathogenesis that is

not well understood[34].

> Porins : Por A and Por B are porins

through which small nutrients diffuse to the bacterium and they are also

involved in host cell interactions and they are targets for bactericidal

antibodies.Por A is the main component of vesicle based vaccines and a target

for bactericidal antibodies while Por B insert in membranes and induce Ca 2+

influx and activates TLR2 causing cell death[34].

11

? Iron binding proteins: They enable the

meningococci to acquire iron which is an important growth factor during

colonization and disease[34].

World's Health Organization policy's of epidemic containments

prevents at best 50% of cases, therefore for an effective prevention of

meningococcal meningitis in sub Saharan Africa, there should be a strict and

effective follow up of universal vaccination recommendation, but still more

than half of cases among infants less than 1 year are caused by serogroup B

meningococci for which no vaccins is available. Also serogroup X, previously a

rare cause of sporadic meningitis, has been responsible for outbreaks between

2006 and 2010 in Kenya, Niger, Togo, Uganda, and Burkina Faso, the latter with

1,300 cases among the 6, 732 reported annual cases [9][

32].

II.3) RISK FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH THE OCCURENCE OF

BACTERIAL MENINGITIS IN CHILDREN

The human infection with meningitis has seasonal variation and

this differs from one country to another [33]. Worldwide

meningitis was estimated to cause 1.73.000 deaths in 2002, most children from

the developing countries [35]. Bacterial meningitis as any

other disease has factors that may be associated to its development, and they

can be preventable or not as follows;

? AGE: The first age group (less than 1year)

occupies the highest number of incidence of the disease which tends to be

higher in developing countries than developed countries. The cause might be due

to the immaturity of immune system, lack in the pre-exposure of the body to the

most incriminated organisms which enhances the memory of the immune system to

fight against the invaders[33].

? GEOGRAPHIC ZONE AND CLIMATE: Bacterial

meningitis is endemic in the sub-Saharan region of Africa, especially in those

countries that are included in the «Meningitis Belt» which is made up

of 26 countries from the Senegal to the West to Ethiopia to the East.

Meningitis in tropical areas occurs in dry season and decrease in periods of

rains, while in temperate regions, the epidemics usually occur during winter

and spring seasons [13][ 33].

? SEX: The male sex has been observed in

various studies to be a risk factor for bacterial meningitis. It is not yet

well understood why males will be more susceptible to getting the disease than

female sex [33].

12

? LOW SOCIOECONOMIC STATE AND CROWDING LIVING

CONDITIONS: These are factors that are mostly seen in developing

countries.Crowdness encourage development of meningitis since most of the

detected pathogens are air transmissible [33][35].

? PASSIVE SMOKING: Children exposed to

smoking are found to get meningitis because, passive smokers tends to harbor a

greater number of bacteria in their throat and nasal passage. Also smoking

plays an important role in diminishing the capacity of epithelial cells

covering the respiratory tract for prevention of acquiring infection in

addition to the prevalence of healthy carrier of pathogens [33][

35].

? RECENT UPPER RESPIRATORY TRACT INFECTION:

This can easily be explained by the route of entrance of the

microorganisms to the brain and those important routes of infection are: Otitis

media, mastoiditis, sinusitis and pneumoniae [33].

? HISTORY OF HEAD INJURY AND BRAIN SURGERY:

It is considered an important risk for development of bacterial

meningitis, because of the proximity of the injury with the central nervous

system [33].

? MALNUTRITION: Malnutrition is a complex

disease that if not well controlled affects every system of the body including

the hematopoietic system, and most of the time complicates with anemia. Anemic

patients are highly susceptible to serious infections such as bacterial

meningitis and can be caused by different etiologies [35]. OTHER

FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH THE DEVELOPMENT OF BACTERIAL MENINGITIS:

? Bottle feeding[33]

? Compromised immune system[33]

? Splenectomy[33]

? Sickle cell disease[33]

? Inherited family tendency for

meningitis[33]

II.4) PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF BACTERIAL MENINGITIS

There are conditions required to cause invasive diseases such as :

II.4.1) BACTERIAL INVASION

Bacteria reach the central nervous system either by

hematogenous spread or by contiguity like in the case of neonates and children

where pathogens are acquired from

13

non-sterile maternal genital secretions and from organisms

that colonize the upper respiratory tract respectively[29]

Successful colonization of the nasopharyngeal mucosa depends

on the ability of bacteria to evade host defenses including secretory Ig A and

ciliary clearance mechanisms, and to adhere to mucosal epithelium[29].

Microbial virulence factors include the Ig A protease secreted by Neisseria

meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae that

cleave Ig A to an active form. Notably meningococus depends on the binding of

fimbriae on the bacterial cell surface to adhere on epithelial cells, and

non-encapsulated strains of meningococci adhere better than capsulated strains.

As the mucosa has been breached and the intravascular space has been entered,

the pathogen must survive in the circulation in order to penetrate the blood

brain barrier[36]. The principal host defense mechanism is complement although

neutrophil and antibodies are also important(Figure 4). The meningeal pathogens

are all capsulated and this virulence factor of theirs enables them to evade

phagocytosis and bactericidal activity of the complement system. In

Streptococcus pneumoniae infection, the alternative complement pathway

is activated by pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides, where there is direct

cleavage of the C3 which generates C3b which opsonizes the organism, enhancing

phagocytic clearance from the circulation[37]. The C3b then binds to Factor B

on the pneumococcal capsular surface offering resistance to opsonisation.

Therefore, it is understandable why individuals with impaired complement

systems are at high risk of getting all the manifestations of invasive

pneumococcal disease.

Neisseria meningitidis, has its capsular sialic acids

which facilitates binding to the C3b to the complement regulatory protein

Factor H, thus blocking activation of the alternative pathway by presenting the

binding of C3b to factor B[36].

In order to cross the blood brain barrier and to overcome

structures such as tight junctions, meningeal pathogens carry effective

molecular tools. They cross the blood brain barrier to enter the subarachnoid

space and are aided with the presence of specific surface bacterial proteins

like E. coli proteins IbeA,IbeB and ompA, Streptococcal proteins such

as CbpA which interacts with glycoconjugate receptor of phosphorlcholine with

platelet activating factor (PAF) on the eukaryotic cells and promotes

endocytosis and crossing the blood brain barrier.N. meningitidis

proteins Opc,

14

Opa, PilC, and a Pili protein[36]. Bacteria causing meningitis

in newborns, most importantly group B streptococcal and Escherichia coli are

also well equipped with adhesive proteins allowing them to invade the central

nervous system[37].

II.4.2) INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE

The lack of host defenses in the CSF allows rapid

multiplication of bacterial pathogens resulting in the release of microbial

products such as lipopolysaccharide[36]. The hall mark of bacterial meningitis

is recruitments of neutrophils into the cerebo spinal fluid(Figure 4)[37].

Neutrophil extravasation to any site of inflammation depends on the coordinated

sequential expression at the cell surface of specific adhesion molecule,

notably L-selectin (CD62l) is expressed at the cell surface and allows the

neutrophil to «roll» along the endothelium.For extravasation to

proceed L-selectin must be removed from the surface of neutrophil and

expression of the B2 integrin CD11b /CD18 must be upregulated[36].

Neutrophil adherence to endothelium occurs through the

interaction of neutrophil CD11b/CD18 and diapedesis and migration of neutrophil

along a chemotactic gradient to focus of inflammation that follows. The removal

of L-selectin and integrin upregulation are achieved by neutrophil activation

which occurs when the cell encounters activated endothelium (IL-8 and PAF are

typical activators of endothelium)[36].

II.4.3) RAISED INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE

Intracranial pressure often rises in meningitis and can lead

to life threatening cerebral herniation. Three pathophysiologic mechanisms

contribute to the development of cerebral oedema[37]. They are;Vasogenic,

Cytotoxic and Interstitialoedema. Vasogenicoedema occurs directly as a result

of the increased permeability of the blood brain barrier[37]. Cytotoxic oedema

is the rise in intracellular water due to loss of cellular homeostatic

mechanism and cell membranes function, attributed to the release of toxins from

neutrophil or organisms. Anti-diuretic hormone (ADH) release leads to

hypotonicity of cerebral extracellular fluid and increase the permeability of

the brain to water. Interstitial oedema is the result of an imbalance between

cerebo spinal production and resorption, and occurs when blood flow or cerebo

spinal resorption is impaired[37].

15

Figure 4 : Pathogenesis of bacterial meningitis

[38]

II.4.4) NEURONAL DAMAGE

Bacterial meninges causes disabling neuropsychological

deficits in up to 50 % of its survivors with the hippocampus most affected and

vulnerable area of the brain. The extracellular fluid around the brain cell is

contiguous with the cerebo spinal fluid and the proximity to the ventricular

system allows diffusion between those compartments around could deliver soluble

bacterial and inflammatory toxic mediators[37].

16

Neuronal damage in meninges involve bacterial toxins,

cytotoxic products of immune competent cells and indirect pathology secondary

to intracranial complications(Figure 4)[38]. In the case of Streptococcus

pneumoniae is associated with the highest frequency of neuronal damage, produce

two major toxins identified; H2O2 and Pneumolysin a pore forming cytolysin[37].

They cause programmed death of neurons and microglia by inducing rapid

mitochondrial damage. Pneumolysin translocate to mitochondria and induce pore

formation in mitochondrial membranes. Release of apoptosis inducing factor

(AIF) from damaged mitochondria leads to fragmentation of DNA and apoptosis

like cell death[37]. The cell death is executed in the Caspase-independent

manner, where cells exposed to live Pneumolysin cannot be rescued by caspase

inhibitors but somehow any intervention from those inhibitors, z-VAD-fmk there

is a 50% chance to avoid neuronal damage[37].

II.5) DIAGNOSIS OF MENINGITIS IN CHILDREN

II.5.1) CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS OF MENINGITIS IN

CHILDREN

The clinical symptoms and signs of bacterial meningitis in

children vary depending on the age of the child and duration of disease. The

classic symptoms of meningitis are fever, headache, photophobia and neck

stiffness. However, in the early stages of meningitis, and particularly in

young children, the symptoms of meningitis can be variable or nonspecific and

the classic symptoms may be absent, making meningitis difficult to diagnose.

Nonspecific signs include abnormal vital signs such as tachycardia and fever,

poor feeding, irritability, lethargy, and vomiting [23][

39].

Children may have fever and vomiting associated with

irritability, drowsiness and confusion. They may become suddenly ill with fever

and rigors, which can be mistaken for seizures. Also muscle and joint aches can

occur which can be responsible for children being restless and miserable.

Vomiting, nausea and poor appetite are common while abdominal pain and diarrhea

are less common. Meningitis causes a rise in intracranial pressure [39

]. It presents in babies and in young children as a bulging or full

fontanel. In children without an open fontanel, raised intracranial pressure is

seen as other features like systemic hypertension with bradycardia. Children

may have an abnormal tone, jerky movements or be floppy

[39][40].

Other children are more likely to have the classic features of

meningitis, fever, vomiting and headache, stiff neck and photophobia.

17

Rashes may be present, most commonly when the causative

organism is Neisseria meningitidis, but more likely to be absent,

atypical, scarce or petechial in character than those seen in meningococcal

septicemia [41].

II.5.2) PARACLINICAL DIAGNOSIS OF BACTERIAL MENINGITIS

II.5.2.1) LUMBAR PUCTURE AND CSF ANALYSIS

A lumbar puncture and CSF analysis is the gold standard and

definitive diagnosis of bacterial meningitis. It is done in either sitting or

lateral decubitus position and is important to monitor the patient visually and

with a pulse oximetry for any signs of respiratory difficulties as a result of

the assumed position.

The subarachnoid space should be entered below the level of

spinal cord termination (Figure 5), and any of the interspace between L3 -L4

and L5 -S1 in children

Analysis of CSF should include: Gram stain and cultures; white

blood cell (WBC) count and differential; Glucose and protein concentrations;

Cytocentrifugation of the CSF enhancing the ability to detect bacteria and

perform a more accurate determination of the WBC differential

[23].

Figure 5: Lumbar spine anatomy[41].

18

Typically, the CSF white cell count (wcc) is >1000

cells/mm3 although it may not be elevated in the early phase of the infection

and the majority of white cells are polymorph nuclear (PMNs). CSF protein is

typically elevated (100-200 mg/dL) and glucose low (CSF to serum ratio <0.4)

[23]

A reduced absolute CSF concentration of glucose is as

sensitive as the CSF-to serum glucose ratio in the diagnosis of bacterial

meningitis [21]

The Gram-stained smear of CSF has a lower limit of detection

of about 105 colony-forming units/mL. Of patients with untreated bacterial

meningitis, 80% to 90% have a positive CSF Gram stain. Unless unusual

pathogens, such as anaerobes, are suspected, agar plate cultures of CSF are

preferred to liquid media [21][ 23].Pleocytosis is a typical

finding in bacterial meningitis, the WBC count usually greater than 1000

cells/mm3, and there is a predominance of polymorphornuclear leukocytes.

The lumbar puncture for the cerebro spinal analysis should be

performed once the diagnosis of meningitis is suspected and after the patient

is stabilised. However, there can be reasons to delay lumbar puncture which

include the following

+ Local site for lumbar puncture: Skin infection at site of

lumbar puncture, and

anatomical abnormality at the site of lumbar puncture

site[42]

+ Patient instability: Respiratory or cardiovascular compromise,

and continuing

seizure activity[42]

+ Suspicion of space occupying lesion [42]

+ Raised intracranial pressure[42]

+ Focal seizures[42]

+ Focal neurological signs[42]

+ Reduced conscious state of GCS less than 8 and especially if

patient is comatose[42]

+ Decerebrate or decorticate posturing[42]

+ Fixed dilated or unequal pupils[42]

+ Absent dolls eye movement[42]

+ Papilledema [42]

+ Hypertension or bradycardia[42]

+ Irregular respirations[42]

+ Anticoagulations and bleeding disorders[42]

19

II.5.2.2) COMPLICATIONS OF LUMBAR PUNCTURE

As in any other procedure, there might be complications after,

and in lumbar puncture some complications have being observed such as;

1. Postural puncture headache (PDPH): It is usually

self-limiting, but when serious, supportive treatment for the PDPH and its

accompanying symptoms include: bed rest, analgesics, hydration,

corticosteroids, and anti-emetic medications [43]. Also in

case of severe and persistent headaches, injecting saline into the epidural

space may be therapeutic [43].

2. Local back pain [43]

3. Infection[43]

4. Spinal hematoma[43]

5. Subarachnoid epidermal cyst[43]

6. Apnea[43]

7. Herniation (post procedural cerebral herniation):

Herniation can be the direct cause of death in around 30% of such children.

Therefore, it is practical to perform cranial CT imaging to evaluate any such

abnormalities before performing an LP [41][ 43].

8. Transient limp or paresthesia[43]

9. Transient ocular palsy[43]

10. Cerebral Herniation[43]

II.5.3) OTHER LABORATORY INVESTIGATIONS

Despite the fact that CSF analysis from lumbar

puncture is the gold standard in the diagnosis of meningitis , some other tests

could be performed like the following:

? C-REACTIVE PROTEIN (CRP) :

Clinically it is not easy to differentiate between bacterial and viral

etiologies in patients with suspected meningitis, and due to the high mortality

rate and potential neurological sequelae in survivors, there is an urgent need

for rapid diagnosis with a near 100 % sensitivity. CRP was used and is still

used as the biomarker for inflammation and tends to be elevated in both viral

and bacterial infections, limiting its ability to discriminate between

bacterial and viral etiologies of meningitis [44].

20

? PROCALCITONIN :Procalcitonin (PCT) is now

considered to be the best candidate to replace CRP due to its high diagnostic

accuracy in various infectious pathologies, including sepsis, acute infections,

endocarditis, and pancreatitis. Normal PCT levels of healthy individuals are

less than 0.1ng/ml and level increase drastically in response to bacterial

infections, unlike CRP, PCT has not been reported to the elevated in viral

infections, thus conferring it to the important ability to distinguish easily

between bacterial and viral etiologies [44].

- PCT also shows utility in the early diagnosis of meningitis

by rising after 4h, peaking at 6h and remaining elevated over 24 h. This is in

contrast to CRP, which rises over 6-12h and peaks at 24 -48 h. This delay in

diagnosis combined with the traditional 72h wait for results of Gram stains,

often results in patients receiving empiric antibiotics

[44].

? Full blood count, Serum electrolytes and Coagulation

studies: Normally these investigations are required initially before

thinking about lumbar puncture, in order to assess for sepsis complications

[21].

? Serum Glucose: This test must be measured

routinely in a child having meningitis, since in a state of hypoglycaemia (low

glucose in blood) seizure might occur and it can be the cause of convulsion in

children apart from the presence of uncontrolled fever

[21].

? Blood Cultures: Cultures are also important

in the diagnosis of the disease especially in those patients having

contraindications towards lumbar puncture [21].

? Normally all the above usually changes in a

declining pattern after the introduction of antibiotics , but some authors

propose Latex agglutination , as a reliable test to detect bacterial capsular

antigens in patients with suspected bacterial meningitis and have been

receiving antibiotics all the time lumbar puncture was performed and it is also

estimated that in the future a more sensitive technique like 16rRNA gene by

polymerase chain reaction might help in the diagnosis of bacterial meningitis

in patients already on antibiotics[23].

21

II.5.3.1) IMAGING TECHNIQUES

? COMPUTED TOPOGRAPHIC SCAN (CT SCAN): This

should normally be done before lumbar puncture in order to rule out any

presence of raised intracranial pressure in order to avoid brain herniation

during a lumbar puncture performance. Now it should be noted that, CT SCAN is

not sensitive at 100%, because a normal SCAN does not absolutely exclude

subsequent risk of herniation[21].

? MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING (MRI): It is

also useful in the diagnosis meningitis and is more sensitive than the SCAN

with the fact that, it is able to show extensive inflammatory tissue

destruction of the meninges in their different spaces, also detects pus and

thus can be used when the others are not available or feasible[45].

II.6) CURRENT TREATMENT ON BACTERIAL MENINGITIS IN

CHILDREN

The three major aspects of treatment of bacterial meningitis

include (1) antibiotic therapy (2) fluid restriction (3) adjunctive therapy

[21].

II.6.1) ANTIBIOTIC TREATMENT

Most treatment guidelines recommend the use of a

third-generation cephalosporin (such as ceftriaxone or cefotaxime) in

conjunction with vancomycin as initial antibiotic therapy. Cefotaxime and

ceftriaxone have excellent activity against all Hib and N.

meningitidis strains [46].

Increasing resistance of S. pneumoniae to penicillins has been

reported, and although cefotaxime and ceftriaxone remain active against many

penicillin-resistant pneumococcal strains, treatment failure has been reported,

hence the addition of empirical vancomycin [46].

In resource limited settings the treatment of paediatric BM

generally has two protocols based on age (under 2 months and above 2 months of

age).Accordingly, for neonates and young infants (under 2 months of age) the

first-line antibiotics are Ampicillin and Gentamicin and alternatives, a

third-generation cephalosporin, such as Ceftriaxone or Cefotaxime plus

Gentamycin.For infants and children (above 2 months of age) the first line is

the combination of Penicillin G and Chloramphenicol and the alternative is

Ceftriaxone, or Cefotaxime [2].

22

II.6.2) ADJUVANT THERAPY AND SUPPORTIVE THERAPY

Recommended dexamethasone dosing regimens range from 0.6 to

0.8 mg/kg daily in two or three divided doses for 2 days to 1 mg/kg in four

divided doses for 2 to 4 days [47][48].

For optimal results, the first dose of dexamethasone could be

administered before, but due to its side effects in children like duodenal

perforation, it is better to administered it,concomitant with the first

parenteral antibiotic dose, since in either way the efficacy of the

corticosteroid still remains the same.

Control and prevention of seizures can be attained with

anticonvulsant medications; benzodiazepines, phenytoin, and phenobarbital are

commonly used for this purpose [21].

II.6.3) FLUID RESTRICTION

In general, it is a common practice to restrict fluids to two

thirds or three quarters of the daily maintenance during the management of

childhood meningitis. The basis for this practice is the need to reduce the

likelihood of the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone

(SIADH). SIADH is characterized by hyponatraemia, fluid retention and a

tendency to worsen cerebral oedema in meningitis. Therefore, practitioners

reduce fluid therapy in children with meningitis in the hope of preventing

SIADH [21].

II.7 PREVENTION OF BACTERIAL MENINGITIS IN CHILDREN

II.7.1) VACCINATION

Vaccination is the immunisation of someone against an

infectious disease through the administration of a vaccine. These vaccins act

by stimulating the immune system, thereby protecting from infection and / or

disease (WHO)[49]. Bacterial meningitis even though still an aggressive

infection, is preventable with the use of vaccines against its different

etiologies introduced and served mostly in children with less than 2 years of

age. This is because these children are more susceptible to infection with

encapsulated bacteria because of their immature immune system to respond

against the bacterium polysaccharide antigens[50].

23

Approximately 3/4 of deaths due to meningitis are prevented

with Hib and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines,which reduce nasopharyngeal

carriage of these organisms in the host and induce immunity[51].

Pneumococcal vaccins are available in two forms [52]:

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine which is served in children

with less than 2 years of age and protects them against severe forms of

pneumococcal disease like; pneumoniae, meningitis and bacteremia.Two conjugates

are used PCV 13 with 13 serotypes and PCV 10 with 10 serotypes which are

relatively well tolerated. WHO recommends three primary doses starting as early

as 6 weeks of age or as an alternative, two primary doses could be given at the

age of 6 months plus a booster dose at 9- 15 months of age[53].

Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine which is served in adults

of greater than or equal to 65 years of age[53].

The different meningococcal polysaccharide vaccines include:

Bivalent(A and C)

Trivalent (A,C and W135)

Tetravalent (A,C,Y and W135)[54]

The Group A and C vaccines have a short term immunisation

effects in older children and adults and it should be noted that group C only

does not prevent disease in children with less than 2 years of age. Meanwhile

polysaccharide Y and W135 are efficient in children greater than 2 years of

age.Tetravalent vaccines are administered in single dose and in children as

from 1 year.These vaccines have as role to induce T cell 6 dependent immune

response and to reduce the nasopharyngeal carriage of meningococci[54].

The anti-Hib vaccine is mixed with a set of four other

vaccines (Pentavalent vaccine) which are vaccines against; diphtheria,

hepatitis B, tetanus and pertussis.Normally three doses are to be administered

for a good immunity, and the first dose is served as from 6 weeks. It can be

administered to 18 months maximum with atleast four weeks spacing in between

the doses[55].

24

II.7.2) CHEMOPROPHYLAXIS

Close contacts of all children with meningococcal meningitis

should receive chemoprophylaxis (ceftriaxone, rifampin, or ciprofloxacin), and

contacts of those with Hib should receive ceftriaxone or

rifampin[21].

Rifampin is administered 10 mg /Kg of body weight every 12

hours for children greater than or equal to 1 month of age, and 5 mg /Kg every

12 hours for infants less than 1 month of age. Rifampin is effective in the

eradication of nasopharyngeal carriage of Neisseria meningitidis. In

addition to rifampin, other antimicrobials are effective in the reduction of

nasopharyngeal carriage of meningococcal pathogens, like ciprofloxacin but

generally not recommended for persons less than 18 years of age because of its

destructive effect on cartilage. Whereas ceftriaxone administered in a single

dose of 125 mg in children is also effective [55].

Unvaccinated children less than 5 years of age should also be

vaccinated against H. influenzae as soon as possible. Patients should

be kept in respiratory isolation for at least the first 24 hours after

commencing antibiotic therapy [21].

II.7) COMPLICATIONS OF BACTERIAL MENINGITIS IN

CHILDREN

Meningococcal disease remains a major cause of morbidity and

mortality in childhood. Neurological disorders in children are common

occurrences in clinical practice. The disorder accounts for more than 170.000

deaths worldwide each year with majority of people affected living in Africa

[56][ 57].

Young children are particularly vulnerable to bacterial

meningitis, and when exposed poor outcomes may occur due to the immaturity of

their immune systems [57]. Two thirds of meningitis deaths in

low income countries occur among children less than 15 years of age. These

complications could be classified as [57]; short term, middle

term and long term.

SHORT TERM

- Brain edema is an early life threatening

complication, in which brain structure changes is not usually found in 80%, but

the residual stage of bacterial meningitis is characterised by cerebral

destructive /proliferative or atrophic changes of different severity

[58].

-

25

MID TERM

- Seizure could be placed in this term. Most

children present with recurrent seizure disorder.Seizures that occur early in

the course of bacterial meningitis are easily controlled and are rarely

associated with permanent or long term neurologic complications. In contrast,

seizures that are prolonged, difficult to control, or begin more than 72 hours

after hospitalization are more likely to be associated with neurologic

sequelae, suggesting that a cerebrovascular complication may have occurred

[57].

- Paresis: It is usually present but resolve

with time, which typically resolves from and intracranial abnormality suh as;

cortical vein, sagittal vein thrombosis, central artery spasm, subdural

effusion or empyema and cerebral infarct [57].

LONG TERM

The incidence , type and severity of sequelae is influenced by

infecting organisms, age of child and severity of acute illness , but it can be

difficult to predict with children.The potential impact of the illness is

further complicated by the fact that some of these sequelae may not become

apparent until months or years after the acute illness.These long term

complications include ;Visual loss ,Cognitive delay, Speech/language

disorders[,Behavioral problems,motor delay/impairment and attention deficit

hyperactivity[57].

- Hearing loss: It might be transient or

permanent. Transient hearing loss may be secondary to a conductive disturbance

affecting many patients. Permanent damage results from damage to the eighth

cranial nerves, bacterial invasion, cochlea or labyrinth induced by direct

bacterial invasion and /or inflammatory response elicited by the infection

[57].

26

II.8) PUBLICATIONS ON MENINGITIS OUT OF

AFRICA

· Almuneef et al in 1998 analysed bacterial etiologies

and outcome of childhood meningitis in Saudi Arabia and in his study there was

a predominance of female sex, also the most affected age being from 3 months of

age to 5 years. The presenting complaints in his study appearing in order of

decreasing frequency were; fever 86 %, vomiting 29 %, poor feeding 19 %,

seizure 14 % and lethargy 14 %[59]

· Franco -Paredes et al reviewed acute bacterial

meningitis cases in 2008, in Mexican patients aged from 1 month of age to 18

years, recorded the most affected group by bacterial meningitis to be between

1-6 months, with Hib being the common pathogen found in 50% of cases. Incidence

proven to have declined significantly after the introduction of appropriate

vaccins [60].

· Nicole Le Saux in 2014 reviewed the current

epidemiology of bacterial meningitis in children beyond the neonatal period in

Canada, and came to the conclusion that the incidence of bacterial meningitis

in infants and children has decrease since the routine use of conjugated

vaccines targeting Hib, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Neisseria

meningitidis [61]

· Polkowska et al presented in Finland Streptococcus

pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis to be the most common pathogens with an

incidence drop from 1.88 to 0.70 in 2014[62].

· Incidence of bacterial meningitis dropped in Japan

from the records of Shingoh in 2015 of 1.19 in 2009-2010 to 0.37 in 2013 -2015,

confirming the efficacy of the Hib and PCV introduction

[63].

IN AFRICA

· In Niamey, in Niger in 1999, using a retrospective

surveillance on cases of laboratory diagnosed bacterial meningitis from

1981-1996 showed that the majority of cases were caused by Neisseria

meningitidisat 57 %, and there was a predominance of meningitis in males

occurring the dry season[64]

· Koko in Libreville, Gabon had predominance in the

female sex among the admissions of children with bacterial meningitis in 2000,

he also noted the highest mortality in children with less than 1 year of

age[65]

·

27

Mullan et al in 2011, evaluating records of cerebrospinal

fluid samples between 2000 to 2008 at Princess Marina hospital in Gabonone,

Botswana, reported Streptococcuspneumoniae(n=125) and

Haemophilusinfluenzae(n=60) to be the most common bacteria cultured,

present in less than or equal to 12 years old and less than 5 years

respectively. The author also reported the climatic tendency of the pathogens,

where Haemophilus influenza was mostly common between April and

September, while Streptococcus pneumoniae most common between May and

October[66]

· In Nigeria , Frank - Briggs in a study followed

patients post meningitis to assess outcome post admissions in 2013 , and had 94

cases with neurological sequelae, notably recurrent seizures being the most

common complication[57].

· Touré et al recorded a total number of 31 cases

out of 833 CSF specimens analysed and had Streptococcus pneumoniae,

followed by Neisseria meningitidis being the most common pathogens

[8].

IN CAMEROON

· Sile et al in a study done in Garoua Provincial

Hospital in the North region of Cameroon in 1999, reported bacterial meningitis

to be responsible for 5 % of consultations and 9 % of hospitalisation. Children

less than 5 years affected at 41 % [67].

· Fonkoua et al conducted a study in 2001 at Centre

Louis Pasteur in Yaoundé, demonstrated that the main etiological agents

detected in samples of cerebrospinal fluid sent to this laboratory, were

Streptococcus pneumoniae at 56%, followed by Haemophilus

influenzae 18%, also noting that, the 4 strains of Neisseria

meningitidis of serotypes W135 were found isolated[68]

· Gervaix et al reported in 2012 in a study that only 62

% of theStreptococcuspneumoniaetype in Cameroon are covered by

vaccins, bringing out the question on the certainty of the vaccination against

bacterial meningitis and its impact in this country[69]

· Nguefack et al demonstrated in 2014 in a retrospective

study conducted at YGOPH that the incidence of bacterial meningitis was high in

Cameroon with Haemophilus influenzae being the most common pathogen

responsible of bacterial meningitis in children with 39.2%, followed by

Streptococcus pneumoniae with 31.6% and

28

Neisseria meningitidis least with 10.5%.There was a

high mortality observed with poor prognostic factors as ; age, attitude in

treatment , pathogen incriminated (for this particular study pneumococcal

meningitis) and emphasis was done on the strengthening of routine immunization

on vaccines preventable diseases of infants and children[3]

29

CHAPTER THREE

MATERIALS AND METHODS

III.1) STUDY DESIGN

This was a retrospective- descriptive cross sectional study.

III.2) DURATION OF THE STUDY

The study went on from the 1st December 2018 till

the 31st May 2019, a period of 6 months.

III.3) STUDY SETTING

This study was carried out at the Yaoundé

Gyneco-Obstetric and Pediatric hospital (YGOPH) at the pediatric unit. This

unit is composed of 3 sub units which are; Hospitalisation 1 and 2 of infants

and young children; External consultation with vaccination; and

Neonatalogy.Hospitalisation 1 has 6 rooms and hospitalisation 2 has 7 rooms

with one isolation room for contagious diseases. The unit is also made up of

instruments such as oxygen extractors (4), aspirators (2) and resuscitators

(2).

The service has an administration made of (1) head of service

and (2) deputy head of services ; medical doctors (12) that is paediatricians

(9) and general practitioners (3); State nurses (20) ; assistant nurses , and

cleaners.

III.4) SAMPLING

There was recruitment of files from a period of 1st

of January 2014 to the 31st of December 2018 of children admitted at

YGOPH who fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

III.5) STUDY POPULATION

Children from 1 month of age to 15 years admitted at the

paediatric unit of YGOPH within the study period.

III.5.1) INCLUSION CRITERIA

- Patients from 1 month of age to 15 years admitted for

bacterial meningitis at YGOPH

- Patients who had bacterial examination of CSF with

identification of the pathogen by culture or soluble antigen

- Patients who had their WBC above 10 cells/mm3.

30

III.5.2) EXCLUSION CRITERIA

- Patients in whom bacterial meningitis has not been confirmed

through examination of csf by culture or soluble antigen

- Any file with incomplete information III.6) SAMPLE

SIZE

N=

d2

The sample size will be calculated using the Cochran's formula:

(??1-??:??)??P(1-P)

Where:

- Z1 - á: 2= is the standard normal

variate at 5% type I error (p<0,005),

- P= expected proportion in the population based on previous

studies or pilot studies, for this study, the proportion from NGUEFACK of

1.54%, 2014 was used [3].

-d= Absolute error or precision.

For our study the numerical application of the above formula was

used:

Z1 - á: 2=1.96; P=0.0514%; d=5%. Then

N=1.96*1.96*0.0154(1-

0.0154)/0.05*0.05=23.29

After plugging in all the information in the

equation, we get a minimum of 23files to collect and use.

III.7) MATERIALS

? Materials of data collection and analysis

o Registered files from the paediatric unit

o A laptop

o Microsoft® Office Excel 2016 and CS PRO 7.2

software for data analysis and Microsoft® Office Word 2016 to

keyboard the thesis.

o A 8 GB flash disk

o A 4 GB flash disk

o

31

Office equipment

o Questionnaire for data collection

o Ballpoint ink-pens, pencils, correction fluid and eraser. ?

Human resources:

o The investigator

o Supervisor and co supervisors

o Collaborators (service of archives, paramedical and medical

personnel)

III.8) METHODS

III.8.1) ADMINISTRATIVE AUTHORIZATIONS AND ETHICAL

CLEARANCE

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Committee of

the Faculty of Health Sciences of the University of Bamenda. Authorization to

carry-out the study at the YGOPH was obtained from the Director General of

YGOPH.

The recruited information's from the questionnaires was held

secret by the investigator in order to maintain data confidentiality taken

throughout the study, and was definitely destroyed through burning after the

data was analyzed and results confirmed.

III.8.2) PATIENT RECRUITMENT

After the approval of the research protocol and the research

authorizations from the different authorities, the personnel in charge of

archives in the pediatric unit were approached. An exhaustive census of all the

children admitted at the pediatric unit with bacterial meningitis within the

study period was done with their admission dates. Then, with information