Again, narrative design in video games is all about cleverly

blending the narrative ropes within the gameplay to shape a coherent and

meaningful experience for the player. Story and plot unfold following player's

progression; in other words, narration in video games is «a collaborative

act between game designers and players» (Picucci 2014). Hades

represents a perfect example to explore that dynamic. Its affiliation to

the roguelite genre induces the use of a specific storytelling process,

delivering a storyline imbedded in a «loop» where player's failure is

expected. In other terms, Supergiant Games' title emphasizes the procedural

rhetoric, a concept coined by Ian Bogost that describes how "rhetoric functions

uniquely" in video games and defines it as such:

I call this new form procedural rhetoric, the art of

persuasion through rule-based representations and interactions rather than the

spoken word, writing, images, or moving pictures. This type of persuasion is

tied to the core affordances of the computer: computers run processes, they

execute calculations and rule-based symbolic manipulations [...] More

specifically, procedural rhetoric is the practice of persuading through

processes in general and computational processes in particular. Just as verbal

rhetoric is useful for both the orator and the audience, and just as written

rhetoric is useful for both the writer and the reader, so procedural rhetoric

is useful for both the programmer and the user, the game designer and the

player. (Bogost 2007, preface IX, 3).

29

Procedural rhetoric designates video games' capacity to tell a

story through repeated processes and interactions, to create the tale from the

gameplay. As underlined by Fregonese , this specific rhetoric can be "applied

by emphasizing on success or failure, obedience or disobedience" (Fregonese

2017, 84, my translation).

Hades purposely relies on its gameplay loop to

create a narrative tension: success and failure both intertwine with the story.

The player must repeat a specific process which further unfold the story each

time. My intents here is to investigate this particular relation between

gameplay and the narratives, and the place of the player in it. Moreover, we

will determine the roguelite's code, and how they were transposed as narrative

tools in the game. Then we will analyze the main character of the game, his

reflection of the player's experience, before focusing on the methods used by

the studio to ensure the narrative continuity.

Death as a narrative feature: Hades, the

roguelite

Hades was created by Supergiant Games and launched

on September, 2020. As displays on the game's Steam page6, the game

is a roguelite, action-RPG, dungeon crawler, where you take control of Zagreus,

son of Hades, and attempt to escape the Underworld. To do so, you get help by

the gods of Olympus who grants you various power-ups.

Before going any further, we have to properly define

roguelite, since the game essentially revolves around that component. In the

first place, genres in video games are hardly normalized; they always change

over time, never to have conventions set in stone. That is not to say they

cannot be defined; however, their definition sustains some porosity over one's

subjective experience--which is why the displayed genres for a game tend to

change from one video game platform to another8. Genres serve to

create expectations over specific elements for the players. With this in mind,

I have no intention to impose my definition; the goal here consists in the

extraction of a roguelite's main characteristics and what the label entails.

6

https://store.steampowered.com/app/1145360/Hades/

8 For instance, while Hades is labeled as

an action roguelite on Steam, it is only referred as action RPG on the Epic

Games Store

https://store.epicgames.com/en-US/p/hades?lang=en-US

30

Roguelite derive from roguelike, an RPG subgenre named after

the 1980's game Rogue, and share most of its characteristics. In 2008,

roguelikes were attributed specific factors at the International Roguelike

Development Conference. The conference's attendants defined Roguelikes with

what is known as the Berlin Interpretation:

· Procedural generation of the game world: the stages,

items and placement of enemies are random.

· Crucial management of resources such as health point

and gold, in order to survive as long as possible.

· Game uniformly grid-based. Whether it is the player or

the enemy, each occupies a predictable space (a tile).

· The game is non-modal: every action (movement,

combats, etc.) takes place in the same mode

· Turn-based game: each command is attributed to a

single action or movement. There is no time limit to perform an action.

· A punishment system (usually permadeath) that forces

the player to start again at the beginning every time they die or fail the

objective.

· Layers of complexity that allow several solutions to a

single objective.

· The player is compelled to conduct careful exploration

and discover usage of unidentified items, which has to be done anew every

time.

· A Hack'n Slash game where it is the player vs the

game's world. The player has no other option but to kill every enemy they

encounter.

The agreed factors listed above were but «an attempt to

define the parameters of the genre» (Brewer 2020). Roguelikes at the time

did not necessarily check all the boxes and today's games labelled as such

certainly do not either. Dead Cells (Motion Twin, 2018), Risk of

Rain 2 (Hopoo Games, 2020) and Neon Abyss (Veewo Games, 2020) all

display the tag «Roguelike» on their Steam Page, while being neither

turn nor grid-based. The genre now largely exceeds the frame of the Berlin

Interpretation, which was already porous to begin with. Which is why

RogueBasin, a community website entirely dedicated to roguelikes, provides a

distinction between roguelikes and «traditional roguelikes». The

latter which refers to games «with a strong focus on Intricate gameplay

and replayability», an «indefinite amount of time» for the

player to «make

31

a move», and «provides new content and challenges on

every run» in an «abstract world representation using characters or

simple sprites» (RogueBasin).

Most of the recent roguelike games are easily distinguished

from traditional ones. Still, they undoubtably uses some of their core designs,

notably the gameplay «loop» generated by the «permadeath

system», the randomization of specific features and the management of

resources, and a challenging experience. The combination of these elements

creates a «die and retry» aspect; replayability is thus a high-value

factor, since players are entailed to replay the game in order to complete

it.

Back to roguelite, this appellation designates an evolution

that toned down some of the Roguelike designs, such as the

«permadeath» which is not a complete restart anymore. Roguelite game

are «colloquially known to feature certain elements of roguelikes, but

presented in a more user-friendly fashion» (Brewer, 2020). A roguelite

game displays a more forgiving game design, in the form of a meta-progression:

even though «permanent» death remains a core element, the reset it

ensues is not total and you still retain persistent abilities, items or

upgrades that make your next attempt at clearing the game easier. You never

truly restart form zero.

So, while Hades falls in the «commonly

accepted» roguelike genre - failure does mean restarting the game - it is

considered a roguelite game since the player undergoes a progression: weapons

can be upgraded, deepened relations with Olympus gods give access to more

powerful boons, some resources unlock permanent perks, etc. I chose here to

make the distinction, because the meta-progression is in fact the core of

Hades. A major part of the game's world is built up using this

feature; above all, the meta-progression is used as a storytelling tool.

During my research, I took an interest in finding what made

Hades a success. One of the reasons was because the game is referred

as a roguelike, a genre that, all in all tend to discourage numerous players

due to how challenging it can be. Hades is certainly not the first

roguelite (or roguelike) to meet with success: The Binding of Isaac

(McMillen & Himsl, 2011), Dead Cells and Into the Breach

(Subset Games, 2018) among others are occurrences of roguelike that

managed to do it too. Nevertheless, Hades seems to have had a stronger

attraction on players that usually dislike this kind of games: When I went over

the Steam review page dedicated to the game9, I noticed

numerous players stating that they enjoyed the game despite having trouble with

other roguelikes. In one player's review, we can read «Whilst I'm not a

fan of these roguelikes, permadeath games usually, I have to say I'm very

impressed with this game; others

9 Hades's steam review page:

https://steamcommunity.com/app/1145360/reviews/?p=1&browsefilter=toprated

32

wrote that they were «not one to play games in this style

usually, but immediately took to Hades» or that it was their

«first roguelike that [they] actually enjoyed.»

While it is not unusual to observe such comment in players'

game review, it did occur a lot in this case. So, I also examined the reasons

Hades won over those players and what emerged the most was «how

good the story was» with the narratives skillfully interlocked with the

gameplay and the progression.» Most of the Press reviews also underlined

those design elements. Gamestop's review stated that «the way story and

gameplay intertwine makes Hades a standout roguelite» (Vazquez 2020). In

the Gamekult's review, Gauthier Andres «Gautoz» states that all in

all, the game is all about its story:

It is the narratives that makes the [game's] world go round.

We live and die for the new weapons, the gods' boons and the fresh cosmetics,

but we fight for the story. Every fiber of that reinvented mythology and every

intimate secret between two capricious gods is snatched by the arrow and the

sword. Then, they come to feed a thick fabric of theories, characters to fully

develop, relationships and surprises lovely prepared by the designers (Gautoz,

2018, my translation).

Not only the story is what Hades focused on, but it

makes sure that every detail about the plot, the characters and the world are

to be accessed through the gameplay - the story unfolds with each attempt at

clearing the game, whether the player fails or not.

It appears then Hades's storytelling is what made

the game particularly appreciated; not just for the story itself but for the

skillfull merging of clear narratives and the roguelite genre that

conventionally does not put story and plot in the spotlight. Hades

makes its world and story shine in a genre where it is not expected.

To hell and back again: playing the game, exploring

the tale

The main character, Zagreus, is determined to leave his

father's domain and go to the outside world, not only because he wishes to be

free of Hades but also because he intends to find Persephone, his birth mother

whom he never knew. Along the way, the gods of Olympus send him messages and

power-ups, for they are eager to see him escape and join them. Unfortunately,

Zagreus's endeavor always ends with him dragging himself out of the pool of

blood [Figure 1], only to try again. Because even when he manages to get out,

he cannot live

33

on the surface but for a short amount of time. Whether Zagreus

dies or manages to get out of the Underworld, he always returns to the starting

point.

Figure 1 - Hades, the

pool of blood that symbolizes both the beginning and the end of the game.

Strictly speaking, each player's run is doomed from the

start. They are stuck in a loop they cannot broken out: whether they clear the

game triggers a reset that entails the player to do it all over again. But for

a game to keep the player playing in those circumstances, it needs to stimulate

its replayability - the basis for a roguelike/lite game. I argue here that what

compels the player to continually engage in Hades is the multitude of

narratives ropes and all they involve.

Supergiant Games earned its renown for its strong focus on

narrative games; their modus operandi is to work «narrative and themes

from the start» and not just create «a story and backsolve the

gameplay onto it» (GDC 2021), for the sake of a good harmony between

design, themes and story. On the GDC podcast, Creg Kasavin explains how they

came up with Hades, their thought process behind its storytelling:

Our mindset was «can we use this genre format to tell a

story?» and a thing I would think about often is, even in the hardest core

roguelike game, where it resets you completely to nothing from one playthrough

to another, there is in fact something that you carry forward which is your

knowledge of the mechanics in the game. Using your knowledge, you can get

farther and farther. So, it was a fun thought exercise to think of a game

premise where the character had the same ability. So, it leads you to

«what sort of character would still remember what happened after they die?

What about a character who's just immortal?

34

Surely, when we stated earlier that the permadeath system in

roguelikes was a complete reset of the game, we could say that it is not

entirely true. In each attempt at beating the game, the player gather

knowledge, whether it is enemies' patterns, position of traps and secrets that

allow them to do better the next time. It follows the die and retry principle

(or «trial and error»), a gameplay mechanic for which the player is

expected to use their death to choose a better course of action afterwards. The

Soulsborne series of FromSoftware for instance is designed around it: the

player is expected to die many times, but also to learn from their failure and

overcome the obstacles. In essence, die and retry can be observed in the

majority of video games, and represent a deep-rooted feature the medium evolved

around. As Jesper Juul said, «we experience failure when playing

games» (Juul 2005, 2), and above all, «it is the threat of failure

that gives us something to do in the first place» (ibid, 45). Supergiant

Games applied this principle directly to Zagreus, whose condition (son of a

god) allows him to «defy» death: like the player, he experiences

failure and acquires knowledge from it, and becomes stronger little by

little.

Zagreus is a character that mirrors the player: both of them

are fully aware of the fate that awaits them upon reaching the surface/beating

the game, but still choose to pursue their doomed endeavor. One character in

particular embodies the meaning behind Zagreus and the player's action:

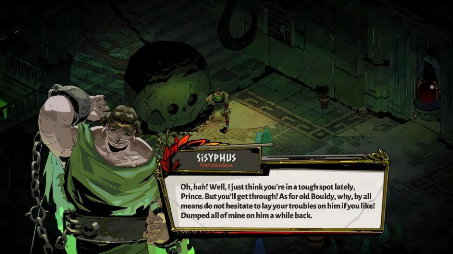

Sisyphus [Figure 2]. Like all the others in the game, Sisyphus is an existing

character in the Greek mythology. His myth portrays him as the most astute

among men, who cheated death not once but twice by deceiving both Thanatos, God

and personification of death, and Hades. For his defiance, Sisyphus was

punished and forced to push a giant boulder up a hill for eternity, as it would

bring him back down every time, he would reach the top.

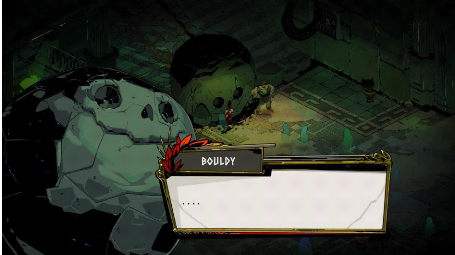

In Hades, Zagreus can encounter Sisyphus,

accompanied by Bouldy (the famous boulder) [Figure 3] in the first part of the

underworld; their discussions, I believe, exposes the philosophical meaning

behind the game, should we talk about Zagreus's story or the player's

experience. Indeed, in the same manner Sisyphus falls all the way down the hill

after he reaches its top, Zagreus (and the player) always ends up in the pool

of blood at Hades's chamber. Even what can be considered as the game's

ending--the culmination of the main story at least-- Zagreus slowly goes back

to the underworld during the credits. Then again, he is asked to

35

continue his escapes, under the pretense of testing Hades'

realm security and upholding the gods' expectation towards him and distract

them.

Figure 2 - Hades, Sysyphus the

tortured soul, an NPC encounter in Tartarus.

Figure 3 - Hades, Bouldy, the boulder

that Sisyphus has to continuously push up a hill.

36

As bleak as it sounds, Zagreus and the player willfully accept

their task, because their quest is not fruitless. Like I have said above, the

story unfolds for each break out and the main plot reveals itself whenever the

player succeeds. The repetitive and supposedly futile endeavor is a central

part of the narrative. Through narrative the player finds commitment; they

embrace the inevitability of enacting the same venture again and again. And it

is not solely about the main plot: as the player wanders through the

underworld, they encounter various characters. For each time they cross their

path, talk to them or offer them gifts, they deepen the relationship between

them and Zagreus. Hence, the player learns more about the game's world while

Zagreus forms connections with those characters. The overall development

represents meaning: each escape attempt allows the player to strengthen those

connections and in a more utilitarian aspect, offers them acquisition such as

legendary weapons that bring new layers of gameplay.

In that sense, enjoyment of the game «comes less from

winning and more from just embracing each new attempt» (Alexander 2021).

Whilst the roguelite's death mechanic create a tension between the narratives

and the player's goal of clearing the game, narratives and gameplay blend

together for the player to enjoy the experience outside of their goal. Along

their many escapes, the player uses distinct weapons with several gameplay

variations - each of the 6 weapons possess 4 forms - discover gods' boons

combinations, secrets, and collect resources to further strengthen Zagreus or

unlock new features. A multitude of elements is consequently used as narrative

features, since they all make their contributions to the world and character

building - weapons for instance belongs to gods or mythological heroes who will

take notice of you wielding them.

The son of Hades himself displays his overall enjoyment of

the situation. With the tedious and madly repetitive task ahead of him, Zagreus

nonetheless shows merriment . Once again, we can draw a parallel between him

and Sisyphus. In Wisecrack's podcast «The philosophy of Hades», Dr.

Kristopher Alexander assimilate Hades's Sisyphus to the one described

in the philosophical essay «Le Mythe de Sisyphe», by French writer

Albert Camus. He points out the absurdity of Sisyphus' task, but despite that

eternal chore, Sisyphus fully accept his condition as shown in [] and in

«his acceptance, he finds contentment, happily going about his task

without ever expecting to achieve anything by it»(Alexander 2021). Indeed,

Albert Camus, largely known for his work on absurdism, describes the

pointlessness of Sisyphus goal to reach the hill - since he is bound to be

dragged down to the bottom - but also that he finds joy in it. Happiness can be

found in the meaningless:

37

Sisyphus silent joy is here. His fate belongs to him. His

boulder is his thing. Likewise, when he contemplates his torments, the absurd

man silences all of the idols [...] I let Sisyphus at the bottom of the

mountain! One can still find his burden. But Sisyphus teaches superior fidelity

that denies the gods and lift the boulders. He too judges that all is fine.

This universe, from now on without master, does not seem futile nor pointless.

All the pieces of this rock, all the mineral shards from the mountain full of

night, all forms a world. The struggle to reach the top is itself enough the

fill a man's heart. One needs to imagine Sisyphus happy (Camus 1942, 94, my

translation).

Even though this is a philosophical approach, it is

interesting to see that Sisyphus mirrors Zagreus's endeavor, and by extension,

that of the player. The latter goes through the same areas and fights the same

foes over and over; as they become accustomed to the task, they progress

further on, until they reach `the top.' The whole endeavor becomes a force of

habit that is executed better each attempt, thus stemming satisfaction. The

player can then continue to enjoy the struggle by making the task harder--a

self-imposed difficulty with the game's heat system--and reenacting the whole

process. Whilst the difference between Sisyphus and the player lies on the fact

that the consecration of the plot and the story development as a whole serve as

meaning, it is also true that those factors are here to induce the player to

engage in a repetitive task.

It surely demonstrates Supergiant Games's intention to

embrace the roguelite genre while giving the player a true narrative

experience; narratives and gameplay respond to each other in a game that is but

an unbreakable loop. A loop that nonetheless keep the player engaged through a

narrative continuity, as explained by Greg Kasavin:

We are always trying to align the player experience with the

narrative and it leads to having a character like Zagreus who can be serious

one moment, self-deprecating another. Even though he has a lot of personality

on his own, in some ways he is there to so to speak for the players' experience

and just try to find that connection between the player's experience and the

story. So, it all kinds of flowed from there, that idea «what if there was

a Rogue Like with narrative continuity where every time you run into a boss,

they remember you. You start keeping track who won this time, who won last

time; it was fun to think about that as a starting point (Kasavin 2021).

The more Zagreus tries to leave the Underworld, the more he

becomes acquainted with the ones guarding it. Each encounter with the bosses

offers pieces of interaction between them and Zagreus. Upon defeating the

second boss of the game (The Bone Hydra) a certain number of times, Zagreus

decides to nickname it «Lernie». Further on, the name is also for the

player to see, indicated above the boss's health bar and on the post-victory

screen [Figure 4]. It adds a sense of unity for the whole game: the player is

still in the loop, but the game's world

38

acknowledges it. Zagreus' relationship with NPCs is not

limited to «friends» but also concern some enemies, who remember

being defeated by him (or not). The first boss Megaera, for instance, can be

talked to afterwards, and the relation may evolve into a romance depending on

the player's choice.

Figure 4 - Hades, The Bone Hydra,

second boss of the game. It is named Lernie after a few confrontations against

Zagreus.

At every turn the game seems to have something to say, even

after the 100th run. Yet, it is very hard to witness a character

that would repeat the same dialogue. That is to say, past the 70 hours into the

game, they are still information and elements about the game world for the

player to look for. The narrative cohesion is a central preoccupation for the

game, it makes sure that the player stays on track with the world building

regardless of how long they play the game. The interactions with the numerous

characters are by no means unlimited, but the pace of the story almost entirely

hides away those limits. As underlined by Gene Park in his article for The

Washington Post, Supergiant Games «limited interaction to maintain

narrative cohesion and immersion» (Park 2020). They made sure that the

player would have a sense of progression, which is why they «can never

talk to another character more than once per return visit» (ibid). It

ascertains the replay value.

39

Again, Hades is the perfect specimen to observe the

narrative relation maintain between the game and the player. The act of play

generates a narrative tension which compels the player to progress through the

game, and thus enact the replayability. Roguelite games are certainly not known

for that kind of storytelling. Narratives in those games are usually more

cryptic, if not hidden away from the player or delivered piece by piece through

fragmented texts and environmental narrative, as in Dead Cells.

Emergent narratives are also common, in Spelunky (Derek Yu 2008) with

no NPC interactions nor dialogues, and an almost entirely generated world, most

of the narratives are to be built by the player. Hades here allowed us

to explore narratives through a "linear" and cyclical form, with the player

embedded in a pre-established story. Gameplay and narratives intertwine to form

the overall play experience: the game's rhetoric is based upon the player's

repeated interactions through the gameplay loop. It indicates a straightforward

storytelling for which the player only determines the pace through success and

fail.

40