URF Langues et Civilisation

Département des Études Anglophones

STORIES & VIDEO GAMES:

INVESTIGATING NARRATIVES THROUGH

PLAY

Mémoire de Master 2

FAUCHIE Quentin

Directeur de Recherche :

Professeur Nicolas Labarre

Juin 2022

2

3

Université Bordeaux Montaigne

UFR Langues et Civilisations

Département des Études Anglophones

Mémoire de Master 2 :

STORIES & VIDEO GAMES: INVESTIGATING

NARRATIVES THROUGH PLAY

FAUCHIE Quentin

Directeur de Recherche :

Professeur Nicolas Labarre

4

Juin 2022

5

6

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENT 9

INTRODUCTION 10

I- Video games and narrative: a story of

interactivity and players 16

A- To narrate a story while playing, to play while

narrating a story 17

To tie gameplay and narratives together, a work of narrative

design 17

Narratives in video games: show, (don't) tell and play 20

Player's agency: to interact or not 25

B- Hades, a story to die for 28

Death as a narrative feature: Hades, the roguelite 29

To hell and back again: playing the game, exploring the tale

32

42

43

II- The world of a game: playground for personal

narratives 41

A A place of Freedom, living and retelling in the

Open-World

Open world, the playground of emergence

Sail close to the game: a player's methodology 50

Emergent narrative in Sea of Thieves: a pirate life for the

player 52

Sea of Thieves, the players and the tales 59

B- The gateway to the virtual world: narratives and

immersion through the avatar 66

Immersion in Video Games, a Work of the Senses 67

Avatar: path into the game, vision of the world. 71

Playing a role, developing an avatar: the legacy of Pen and

Paper RPG 77

C- MMORPGs and the social Heroes: Forging the tales

within a community 86

Online and massively multiplayer: beyond the act of play? 87

The play to the social: investigating emergence from the social

dimension 89

Hero for the history books: player character living the story...

96

... then redefining the tale: author of the endgame and builder

of the community 102

Conclusion 109

Annex: Sea of Thieves related posts sampled

112

Annex 2: Final Fantasy XIV related posts sampled

114

Work Cited 116

7

TABLE OF FIGURES

FIGURE 1 - HADES, THE POOL OF BLOOD THAT SYMBOLIZES BOTH THE

BEGINNING AND THE END OF THE GAME. 33

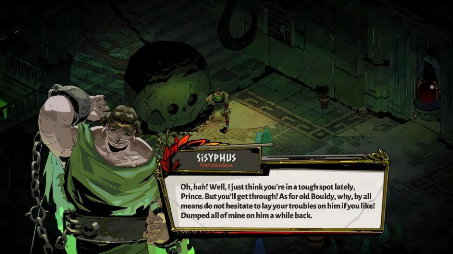

FIGURE 2 - HADES, SYSYPHUS THE TORTURED SOUL, AN NPC ENCOUNTER IN

TARTARUS. 35

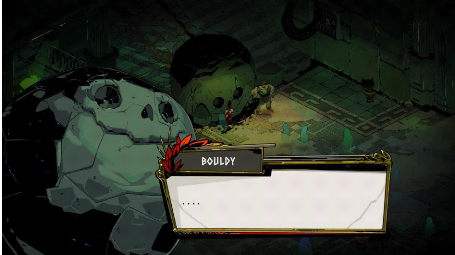

FIGURE 3 - HADES, BOULDY, THE BOULDER THAT SISYPHUS HAS TO

CONTINUOUSLY PUSH UP A HILL. 35

FIGURE 4 - HADES, THE BONE HYDRA, SECOND BOSS OF THE GAME. IT IS

NAMED LERNIE AFTER A FEW CONFRONTATIONS AGAINST

ZAGREUS. 38

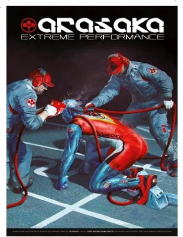

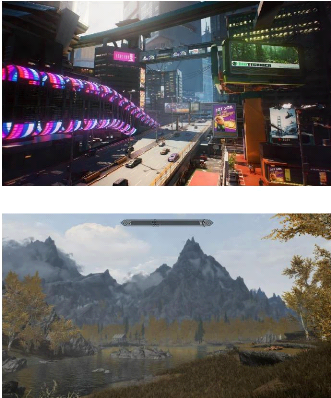

FIGURE 5 - CYBERPUNK 2077, IN-GAME AD IN WHICH A TRACK AND FIELD

RUNNER APPEARS TO BE IN AN F1 PIT STOP 44

FIGURE 6 - CYBERPUNK 2077, CITY CENTER DISTRICT OF NIGHT CITY.

45

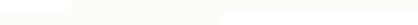

FIGURE 7 - SKYRIM, REGION OF FAILLAISE. 45

FIGURE 8 - SEA OF THIEVES, THE CREW PLAYING MUSIC IN UNISON.

53

FIGURE 9 - SEA OF THIEVES, MY CHARACTER SITTING ON THE BOW. 53

FIGURE 10 - SEA OF THIEVES, RANDOM APPEARANCE OF THE KRAKEN,

KNOWN TO BE THE STRONGEST CREATURE OF THE GAME 55

FIGURE 11 - SEA OF THIEVES, A TALE BOOK THAT CONTAINS INDICATIONS

OR HINTS FOR A TALL TALE. 58

FIGURE 12 - MEME BY REDDIT USER KMVFEFJKLV, REPRESENTING WHAT

PLAYERS TEND TO EXPERIENCE IN SEA OF THIEVES AFTER

CLEARING AN OBJECTIVE (HERE, A FORT). 61

FIGURE 13 - DARK SOULS III, A MESSAGE ON THE GROUND GIVES AND

ADVICE THAT ONLY MAKE SENSE OUTSIDE OF THE GAME. 76

FIGURE 14 - DIVINITY ORIGINAL SIN II, CHARACTER CREATION WITH A

«CUSTOM ORIGIN" 81

FIGURE 15 - DIVINITY ORIGINAL SIN II, CHARACTER CREATION FOR AN

"ORIGIN CHARACTER", HERE THE RED PRINCE. 81

FIGURE 16 - FINAL FANTASY XIV SCREENSHOT BY REDDITOR RENAART.

PLAYERS AS DARK KNIGHTS PAYING TRIBUTE FOR THE LATE

MIURA KENTARO. 92

FIGURE 17 - FINAL FANTASY XIV, MY CHARACTER IN THE

«PERFORMANCE MODE» PLAYING ELECTRIC GUITAR. 94

FIGURE 18 - PICTURE FROM TWITTER USER @CERESCLOUDSXIV. FINAL

FANTASY XIV, MOSH MOSH LIVE CONCERT PERFORMANCE AT

LIMSA LOMINSA. 94

FIGURE 19 - FINAL FANTASY XIV, EXAMPLE OF DIALOGUE TREE OCCURRING

DURING QUESTS. 100

FIGURE 20 - FINAL FANTASY XIV, MY CHARACTER APPEARING IN THE

GAME'S END CREDITS. 101

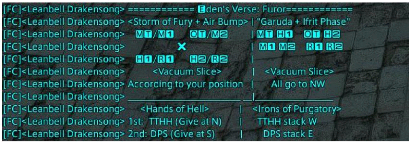

FIGURE 21 - FINAL FANTASY XIV, STRATEGY AND POSITIONS FOR A RAID

SET UP THROUGH A TEXT MACRO POST IN THE CHAT BOX. 104

8

9

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I would like to thank each and every one who accompanied me

throughout the writing of my master Thesis.

First of all, I want to thank my supervisor Professor Nicolas

Labarre, who never failed to help and guide me whenever I needed it. I am all

the more grateful to him for introducing me to game studies. It opened up new

reflection perspectives about a medium I greatly appreciate, and allowed me to

enjoy the time I spent on my research.

Many thanks to my partners in games, Kévin (Xahes),

Antony (Ak_ant), Sébastien (InShuMonki) and all the others with whom I

played, and laughed (a lot), whether it was part of my work or not. The writing

of my thesis was made easier, knowing I could count on them to blow up some

steam at the end of the day.

A special thanks to my flatmates Kévin, who was always

ready for the coffee break, and Léa, an amazing Barista who made us

drink real (and delicious) coffee.

Finally, I want to thank all of the video game creators whose

stories made me who I am now, and forge a medium which allows people to

discover astonishing worlds. I can only hope that my work even remotely gives

back some of what it gave me.

10

INTRODUCTION

Hey! Look! Listen!

[Navi, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time.]

With those three simple words, the many people who once saved

a whole realm from the clutches of the Gerudo King have probably seen some

memories resurface: their terrible struggle within the Water Temple, their

endless wandering in Kokiri Forest, and most of all, this deeply annoying (yet

touching) little fairy that would not care to stop repeating those words.

Others may simply remember a time when they were a genuine hero, dressed in a

now emblematic green tunic and a pointed cap, bearer of the Triforce of

Courage. But these three words are not only about touching upon one's nostalgic

streak; they reflect the story of a video game, the experience of a player. It

is a virtual world upon which players encountered a myriad of characters,

defeated many foes, explored vast areas and deep dungeons. They faced arduous

challenge and learned about a whole new world. Most of all, they went through a

genuine narrative experience.

Nowadays, video games are among the most popular form of

entrainment worldwide. They are part of many people's daily life: we can play

games on consoles, handheld consoles, computer, but also smartphones and with a

VR (virtual reality) headset. There is a game for almost every taste and every

wish, from the pure heavy action game to the turn-based strategy, through the

contemplative adventure. I have played video games most of my life. I have run

at the speed of sound through Green Hill, wandered in the slums of Midgard,

explored numerous Disney worlds guided by a giant key, and probably saved the

world a hundred times. From my point of view, video games have always been

about telling stories, and I believe they have unique ways of doing so. They

enact a form of storytelling that is participatory: we are ourselves the hero

of the story (Ostenson, 2013).

Video games have both a short and long history. Compared to

novels or even cinema, video games are rather new, truly taking shape in the

1970s with the first console and arcade games. On the other hand, the medium is

already more than 60 years old, with the first video game iteration tracing

back to 1961's Steve Russel Spacewar (Newman 2004, 1)--at least it may

be. For video game aficionados, 60 years is definitely a long period: in this

time span, the medium has drastically evolved and has taken many forms,

explored multitude of genres and

11

styles, and has developed various forms of play. Besides the

huge technical gap between now and then, video games are now able to display

huge detailed world, and tell deep, complex stories.

In September 2020, I discover Hades, a roguelite game

developed by Supergiant Games, notably known for Bastion (2011),

Transistor (2014) and Pyre (2018). The title relates the

endeavor of Zagreus, son of Hades, who wishes to escape his father's domain and

find his lost mother. After a few hours playing the game, I find myself

surprised: the game tells a story, with plots and developed characters, and a

compelling one at that. It was a surprise because I did not expect this kind of

experience from Hades, which is labeled as a roguelite by its

designers. Genres in video games are often subjectively established. They serve

to create expectation for the players. Thus, I thought I would play a rather

usual roguelite, in which the overall story stays in the shadow of the game

world's mechanics and the replayability we get with this genre. However, I

delved in a game filled with dialogues, actual plotlines leading to resolution,

and a main narrative arc. Yet it was still a roguelite, with its mechanic

around death that put us inside a loop where we must redo the game each time we

are vanquished.

I thus played a game that cleverly merged its narratives with

the gameplay. A relationship I had not put much thought into until now. It was

appealing to me because I have always been fascinated by the stories video game

made me experienced. Hence, when I was introduced to game studies, it compelled

me to further explore this relation, investigate how video game stories were

told. Not just as a player, but as researcher that feels the need to understand

how it works. Whereas I was very familiar with video games, it was not the case

with game studies. The field of research was mostly unknown to me, especially

regarding the pre-existing theories it had developed for many years. That is to

say, it represented the main difficulty I had to face. I needed to familiarize

myself with a lot of previous works and approach the theoretical concept that

surrounded the medium. Since video games have taken huge technical leap (in

every part of the game design) over a «short» period of time, I had

to pay particular attention to the period in which these works were carried in

order to avoid any kind of misleading direction in the thought process.

Eventually, guided by my thirst for knowledge for the medium

and my attraction for its stories, I chose to study video games narratives'

structure. More precisely, the object of my research is the narrative relation

between the game and the player, how narratives occur through

12

the act of play. Although Hades was the stimulus that

motivated this work, I decided not to solely focus on it. Instead, I extended

my research through several games thus relying on three major ones including

Hades, Sea of Thieves (Rare, 2018), and Final Fantasy XIV

(Square Enix, 2010). For starters, the premise of my work is that every

video game has narrative values. Whether it is through the writing, the

gameplay, or even the environment they put players in, each one of them deliver

a narrative experience. Moreover, addressing different games enables to

highlight the diversity in storytelling devices; the craft of their

storytelling relies on many, if not all, the elements they are composed of

(game design, level design, sound design, etc.). These games were thus selected

with a need to approach narratives from different angles and encompass a rather

large scope. They have also been chosen by taking into account their

«community's» activity, to ensure that I would be able to gather

sufficient data. Thus, I excluded games demonstrating very low player base.

Plus, I directed my focus on them as they were on the press line of sight: to

obtain as much empiric data as possible, I chose these games which were

reviewed, analyzed or just discussed to some degree within the video game

press.

Given the multiple narrative properties of these games we

might consider, I devised my methodology around «participant

observation.» It allowed me to conduct my research as an active unit

within the games (a player), rather than being a sole external observer. The

purpose was to observe the world in which players play «but also

participates at varying degrees» (Nardi 2010, 28) in order to understand

the player practices in it. Since the participant observation aim at an overall

better comprehension of a game's world and its players, the methodology usually

includes data extracted from players interviews. Rather than direct exchanges,

I collected the data using two main sources: the games' dedicated subreddit and

their official forums, from which I sampled a certain number of posts. The

sampling process targeted player's shared experience with the games, that I

intend to compare with my own observations.

Whilst I used references from game studies, especially to

strengthen the theoretical framework, I also supported my research with

multiple press references and insights from developers. Again, given the

evolving nature of the medium, I mainly focused on a rather recent period,

broadly ranging from 2010 to 2022. Of course, I did not disregard earlier

works. Though many of them display analysis which cannot be applied to current

video games, they remain particularly relevant, especially for the different

definitions surrounding the medium. Readings from prominent game studies

figures such as Jesper Juul, Ian bogost or Aarseth Espen provided me with

precious knowledge that certainly helped to produce this thesis.

13

Throughout the whole work, I intend to develop and back my

arguments using meaningful examples from a large ludography, specific mechanic

of gameplay and screenshots from the games. My objective is to explore the

devices video games used to tell stories through a thorough analysis of some of

them. The games I selected are meant to provide a large ground of study

according to their distinct design. The notions of progression (linearity) and

emergence are thus confronted and used to demonstrate how narratives form

throughout the player's experience.

Ultimately, my studies will be guided by one query: How do

narratives intertwine with the act of play and forge the play experience?

In order to properly conduct the following analysis and

examine the various elements brought by the research; the thesis is divided in

two main sections. First is the study of narration within the game studies

pre-established concepts and from the codification adopted in the industry. I

will focus on the inherent relation that links the act of play and the

narratives. Through an analysis of Hades, I will expose how a video

game can tell stories through gameplay. It is about investigating the relation

between the gameplay and the narratives, and how the player is incorporated in

it.

The second, more consequential, section will explore

storytelling using the prism that is the open world design. It will allow to

highlight the narratives occurring when the player is put in free navigable

space. Firstly, from a participant observation conducted in Sea of Thieves,

I will also demonstrate the nature of emergent narratives, how it shapes

the player's experience through the possibility space that enables freedom in

play activities enactment. Then in a second step, I will further expand the

theoretical framework with a deep analysis on the avatar as a character. It

will focus on its immersive properties, but also the influence it has on the

player's perception regarding a virtual world. Among other confronted examples

and academic insights, Divinity: Original Sin II will serve as the

basis for examining the avatar-character in the RPG genre.

Eventually, the last part of the thesis will focus on the

MMORPG and how this particular type of game extends the medium's narrative

scope, notably through its social dimension. Using Final Fantasy XIV

as the main empirical source, I will examine the act of play in a social

environment and what it entails regarding the narratives and the personal story

players fashion from it. Depicting the player in the position of the author

within a whole community, the game

14

further extends the emergent narrative possibility.

Furthermore, with the «endgame,» we will approach an MMORPG aspect

which enables to create personal stories intertwined between the game and its

community.

15

16

I- Video games and narrative: a story of interactivity

and players

Narratives in video games are a much-discussed matter in game

studies - and have been since before the field first gained recognition. With

the medium's growing reliance on strong narratives, it has increasingly drawn

the attention of the academic community, scholars who seek to investigate video

games as storytelling devices and theorize the nature of their narrative

(Koenitz & al. 2013). After all, unlike other media, video games deliver a

story through the player's input: the different techniques for telling a story

involve different approaches in the role the player play within it. On the GDC

(Game Developer Conference) podcast of March 2021, Creg Kasavin, Creative

Director and writer at Supergiant Games (Bastion, Pyre,

Transistor...) shares his view about storytelling in videogames:

I think we have certain value in common from game to game. We

are always interested in that sort of interconnection between the interactive

experience and the narrative experience in context. How can we tell stories in

a unique way that would not translate to other media? How can we take advantage

of what is unique about games in our approach to storytelling (Kasavin

2021)?

To recount a story through a video game is to invite the

player to unfold said story by interacting with the world it is set on. Here,

Creg Kasavin introduces the connection shared by narrative design and the act

of play: contextualizing the game's world, its story and the gameplay mechanics

altogether, for the sake of the player's experience. I intend to observe and

study this relation in Hades, for it is a game that made narrative its

primary strength despite belonging to a genre that usually ignore that aspect.

The analysis that will follow will be focused on how the game's story

contextualizes the mechanics for the players, how it is «told», as

well as the methods used to keep the player engaged with that story. But first,

I believe it is crucial to understand how video games storytelling works, the

rhetoric of narrative elements and their synergy with interactivity, and how

the plots (the events) thread the narratives and form the actual story.

17

A- To narrate a story while playing, to play while

narrating a story

Understanding video games as a storytelling medium can be

difficult, to say the least. A vast array of theories surrounds the notions

attached to the subject, which animated debates in the mid-2000. Ultimately,

story and narrative are shrouded in a certain vagueness when one tries to

extract a precise definition.

To comprehend how a video game story is told, and how it

resonates with the player, it is then essential to establish a framework for

«narrative design». Moreover, for the purpose of studying player's

creativity in relation to a game, we will see several narrative methods and how

they are used. Examining the tensions between narrative and interactivity will

then enable a deeper reflection on how a game resonate with the players, and

shape their experience.

To tie gameplay and narrative together, a work of

narrative design

To pinpoint the exact role of a narrative designer is no easy

task. By observing numerous video game studios, it appears that the scope of

that job remains quite large, and depends on several factors: studio's size,

country, type of game, etc. (Manileve 2021). There is also dissension among

those who share the label: what it means and where the responsibilities lie can

be specific to each individual. Writers and authors sometimes see themselves as

narrative designer, as their responsibilities lay beyond basic writing.

In an article from Ubisoft Stories, in which several narrative

designers were interviewed, Sarah Beaulieu, Associate Narrative Director at

Ubisoft, highlights the disparity of opinions among the industry:

Ask 10 narrative designers to describe their job, and you will

get 10 different answers. Without going into the more technical aspects, I

think the narrative designer is a sort of hybrid, cross-disciplinary role that

spans across game mechanics and narrative. (Beaulieu, 2021)

As it serves both gameplay and narration, narrative design

encompasses a wide range of functions. However, it is not uncommon to have the

narrative designer associated with other roles, especially with

writers--particularly outside of English countries, where jobs terminology

shows even more disparity, since in the first place, many fields of expertise

in the game industry do not necessarily possess a commonly accepted term

(Fregonese 2017, 25).

18

Indeed, both the narrative designer and the writer are

dedicated to the story, and it is true that the line that separates the two

often appears blurry. Julien Charpentier, former Narrative Director and current

Editorial Narrative Advisor Senior at Ubisoft, underline the thin barrier

between the two roles:

I like comparing my job to that of a writer. When an author

starts writing, they systematically go through three different phases:

researching, planning, and drafting. In video games, writing is split in two

halves. The scriptwriter drafts the script and the narrative designer--or

director-- maps everything out. Of course, it isn't clear-cut, and the roles

can overlap, but narrative design is mostly about wielding game systems

(Charpentier 2021).

That is to say, the use of the term within the industry (and

to a certain extent, by scholars) lacks the precision that would otherwise

enable an accurate definition. Nevertheless, narrative design does have a role

in the game development ecosystem. According to Eric Stirpe and Molly Maloney,

respectively Writer and Narrative Designer at Telltale games, writing «is

responsible for the characters,» while design «is responsible for the

player,» mentioning among other things that the latter prevents

«mechanics from feeling different or out of place with the narrative»

(Maloney & Stirpe 2020). In that sense, narrative design is the bridge that

connects the story with the game systems, and by extension, the player. It is

what allows the narrative to make sense out of the gameplay, and it «uses

the gameplay and all visual and acoustic methods to create an entertaining and

stimulating experience for the player» (Mauger 2010, 10).

That intrinsic relation between narratives and gameplay

appears to be one of the narrative design's cores. The designer is in charge of

harmonizing the game design with the story, and has a hand in every corner of

the development team, wherever the story is concerned (sound design, level

design, quest design, etc.). This can be observed in various job applications,

in which studios give a rather precise description of what they expect for a

narrative designer. For that very purpose, I extracted three of them, from

Remedy Entertainment, Kochmedia and Amazon Game Studios:

· If you like the idea of taking ownership and creating

compelling, engaging, and memorable narrative gaming experiences, through

designing and scripting key narrative gameplay systems and content, then this

job is for you! (GameJobs 2021)

· Become a creator, guardian, and advocate of the story,

characters, tone, and storytelling engagement. Team up with game designers to

implement and execute all narrative aspects through mission, level, and game

system design. Design interactive narrative game systems to create a

compelling, emotional gameplay experience. Collaborate with writers and editors

to

19

write, edit and implement game text and dialogue. Shape the

game world and its characters' tone, maintaining its consistency throughout the

game (Koch Media 2021).

· As a Narrative Designer, you'll be responsible for

conceptualizing, writing, and supporting the implementation of quests,

dialogue, lore, and characters in New World. You will work collaboratively with

quest designers, world builders, character designers, and level designers to

create engaging gameplay experiences. It will be a combination of your

experience and an understanding of narrative fundamentals for MMO and RPG quest

design that will define success (GameJobs 2021).

Though it is clear that their role consists in branching the

story, they also have the task to guarantee its consistency with the other game

designers. In each of these three applications, the Narrative Designer not only

manage storytelling, its implementation across the different section of the

team, but they undertake the creation of a gameplay «experience,»

highlighting here again their responsibility towards the player's

experience.

Narrative design works like a hub for every narrative element

in a video game. It coordinates information relative to the storytelling

between each other creators. A narrative designer asserts that they get a good

understanding of the game's story and subsequently allow them to transcribe it

accurately in their respective field. They can thus explain the atmosphere that

should emanate from a particular section of the game to the Level Designer, or

can describe a specific mood needed at a given time to the Sound Design team.

Even so, the role of a Narrative Designer remains dependent of the development

team's size, but also its needs. For instance, Florent Maurin, head of The

Pixel Hunt studio (Inua--a Story of Ice and Time, Enterre-moi Mon

amour), explains that they barely use the term «narrative

design,» stating that as a small independent studio, they «don't

really need to structurally differentiate between narrative design, game

design, and scriptwriting» (Maurin 2021).

Overall, Narrative design may well be the jack of all

trades--just like Game Design-- supervising each part of the creating process

to ensure that narrative and gameplay are in a state of symbiosis. Narrative

design then refers to the branching of an interactive story that uses gameplay

and design tools to create coherent yet stimulating narrative for the player's

experience; that would be the definition I believe suit narrative design the

most, and the one I shall use for my work. Still, it is essential to keep in

mind that the definition retains its porosity, and it is not my intention to

set it in stone. Nonetheless, it is the framework needed from there on, that

will enable to explore deeper narratives within video games.

20

Narratives in video games: show, (don't) tell and

play

Down the line of Narrative Design is, of course, narrative,

which one can broadly define as the art and manners of telling a story and

connect events within it. Scholars were (and still are) very passionate about

the term--whether we talk about video games or not--and which animated strong

debates, most famously in the early 2000s, regarding whether games can tell

stories (Juul 2001), with ludologist on one side and narratologist on the

other. Since then, game studies, as an interdisciplinary field, has moved away

from this binary view, and developed its own array of theories, with the

premises for us to consider video games as neither «purely narrative nor

purely ludological» (Cheng, 2007, 15). In the course of my work, I do not

intend to reiterate debates around narrative, even more so since it remains at

the heart of many studies in literacy as a whole. Nonetheless, for a global

comprehension of video games as a narrative medium, one needs to comprehend the

rhetoric of their narratives, how it is intertwined with both the players and

the gameplay.

The video game industry evolves at a fast pace: should we

even limit our observation to a single decade, the medium's transformation

remains visible. Minus the obvious technical feat, video games are now capable

of deeper and more complex stories, to the point that «story-driven»

(or «Story-rich») often comes out as a genre--or at least a

category--as it is the case on Steam for God of War (Santa Monica

Studio, 2018) or Marvel's Guardians of the Galaxy (Eidos

Montréal 2021) to name but two examples. Sony's PlayStation even focuses

on this «type» of games, stating their commitment «to strong

narrative-driven, single-player games» (Gamesradar 2020). From the first

steps of the creation, the story elements represent the core of the design and

tend to affect both the worldbuilding as well as the gameplay (Picucci 2014).

Beyond the player's appeal for those games, that tendency demonstrates a clear

strengthening in writing, directing, and needless to say, narrative over the

years.

But as Espen Aarseth pointed out, games are not just games,

«they are complex software that can emulate any medium» (Aarseth

2012). Consequently, to summarize narrative as I did above is too

simplistic--while not entirely inaccurate. Video games' narratives, as I

mentioned earlier, extend throughout the other part of the creating process.

Besides recounting the events that form the story, narratives delimit the frame

of the game, the background and blend them within its rules. Each and every

task the player performs potentially becomes part of the story. In Ori and

the Blind Forest (Moon Studios, 2015), we quickly encounter areas that

are

21

inaccessible. In order to reach them, we need to progress

through the game and return with the right abilities or tools--one of the core

principles of what is called metroidvania1. The designers use rules

to constrain the players and coerce them to «come back» later while

at the same time, applying narrative elements for the character's growth (Ori).

Therefore, these elements inevitably reflect the player's progression, which in

turn becomes not just a gameplay mechanic but also a prominent element in the

story's structure.

Compared to what they were when they debuted as a mainstream

medium, video games have now «matured and does not solely relate stories

through text anymore» (Fregonese 2017, 52, my translation); whether it is

a linear narrative with a straight chronological order or a branching narrative

that uses players' choices to work the story like a tree diagram, video games

embrace many different narrative forms with their specificities, their own

purposes, and take advantage of the design diversity the medium can enjoy.

Although that multitude of narratives is by no means

standardized--interpretation and terminology remaining dissimilar between

individuals in the industry and in the academic field--I will use the narrative

denominations found in Pierre-William Fregonese's Book, «Raconteurs

d'Histoires : Les mille visages du scénariste de jeu video,» which

I believe accurately describes the forms broadly used by developers:

· Textual Narrative

The most basic narrative, which develops the story and events

through writing. It encompasses dialogues, quests and in-game documents like

books, letters and every other text which nurture our knowledge about the

game's world. In the simplest form, we find that narrative style within almost

every game, to various degrees. Still, the RPG genre probably use it the most,

since it tends to seek a very detailed worldbuilding. A good example would be

Divinity Original Sin II (Larian Studios 2017); with its deep roots in

tabletop RPG (mostly Dungeons and Dragons in that case), the game

strongly relies on dialogues and the multiple choices the player can make out

of them. The staging essentially happens through texts, with a narrator

describing most of the actions, whether it is the player's or

NPCs'2. On top of that,

1 Metroidvania is a portmanteau word that take its

name from the games Metroid and Castlevania. It is a genre (or subgenre) define

by interconnected level design, back and forth progression (backtracking)

marked by the discovery of items and abilities, and the presence of RPG

elements (Gamekult, Loop, 2018).

2 «NPC» is an acronym that stands for

«non-playable character». It designates every character in a game

that is not under the control of the player.

22

details about the lore can be found among an enormous number

of books and various other types of written work.

· Environmental Narrative

A style of storytelling whose presence has grown along video

games' technological advancement. Environmental narrative focuses on indirect

elements that shape the world the player is exploring. It is «the art of

arranging a careful selection of the objects available in a game world so that

they suggest a story to the player who sees them» (Stewart, 2015). In a

broad sense, it is the story (more like "a sequence of events») related by

the environment and all elements that belongs to it. It can refer to NPC

talking to each other on the background, the background itself (the design it

displays), cutscenes or even specific colors--like the stages in Hades

(Supergiant Games, 2018) that each display a distinct hue. Through a

single look at Night City in Cyberpunk 2077 (CD Projekt, 2020), you

understand the kind of world you set foot on: the explosive number of ads

displayed absolutely everywhere, the characters' behavior, their design... With

those elements, the player's imagination has the needed groundwork to grasp the

world's stakes, and what it means to «live» in it.

· Cyclical Narrative

Cyclical (or circular) narrative refers to a story that

connects its ends to its beginning, thus making a loop. It works more or less

in the same way for video games: the cyclical narrative is based on

«renewal» and «replayability,» with the story expanding

each time the player starts the game over; usually in what is commonly labeled

«New Game +.» The Soulsborne3 series by From Software uses

that principle, with the player facing stronger challenges and discovering new

elements every time they finish the game and starts again, therefore extending

their experience. Other games integrate that type of narrative as an inherent

part of the storytelling, as it is the case for NieR: Automata

(Platinum Games, 2017). Each «new game» let the player discover

the story through a different point of view, with a different playable

character or with new events. They are compelled to see the game through the

end several times in order for the

3 «Soulsborne» or «Souls

Series» refers to the series of game developed by FromSoftware, which

includes Demon Souls, Dark Souls I-III and Bloodborne. Players and journalists

came up with the label since they share very similar game design.

23

true ending to be unfolded. Most roguelite games such as

Hades would also serve as good examples. They rely on a gameplay loop

where the player redoes the game. With Hades, they start the game all

over gain whether they fail or not; each time they do, they progress through

the narratives, obtain more skills, weapons, and learn more about the game's

lore.

· Emergent Narrative

Although we will see emergent narrative in more details later

on, that type of narrative aims at providing unique experiences to each

individual. To put it in a nutshell, the storytelling is essentially made by

the players through the variety of interactions at their disposal. Sea of

Thieves (Rare, 2018) offers above all else the possibility for players to

live their own story (alone or with a crew) within its world. Most of the time,

they are making their own objectives (treasure hunt, naval battle, exploration,

etc.) and use everything they can (like playing music, getting drunk or

fishing) to shape a unique experience each time they play. Hence, the player is

in charge of the story and its direction, free of any intervention from the

authors (Chauvin, Levieux and Donnart, 2014). The strong appeal here is the

replayability it generates, since the player's actions stimulate a persistent

world in which they will often create unexpected and memorable situations.

· Procedural Narrative

Among the narrative style presented here, procedural

narrative may be the hardest to tackle, especially because this type of

narrative is quite recent--at least in its common usage to describe a game's

narrative--and has yet to truly display its potential. More often than not,

procedural narrative is mistaken with emergent narrative, since both of them

seek the unique experience of the players. But while emergent narrative let

players create their own story with numerous interactions allowed by a few

simple rules, the procedural relies over more or less complex algorithms which

generates narratives ensuing from players' action. In other words, it is

reactive stories (not branched nor pre-written) that responds to one's way of

playing. Back in 2016, No Man Sky's built-up player's anticipation

over its supposedly infinite universe with randomly generated planets that

called for never-ending adventure. Though reality came knocking at the door

pretty fast at launch, notably with the complete randomness of planets'

24

wildlife that displayed unfathomable creature4,

players could indeed visit entire galaxy with not a single planet resembling

the other. Perhaps a more relevant example would be Watch Dogs: Legion,

seen as the «most ambitious blockbuster attempts at procedural

storytelling» (The Verge, 2021) in recent years. The gameplay revolves

around a recruitment system that lets you play almost any NPC in the game, each

with their own generated background. Of course, it does not alter the game's

main story, but the system adapts itself to the players.

The list of narrative presented above is not exhaustive and

reflects but the most prominent types. Moreover, as stated by Espen Aarseth,

«there can be no single mode of narrativity in entertainment software,

given the diversity of design solutions» (Aarseth, 2012). Indeed, most of

the time, they are products of various combinations. For instance, and as far

as this list is concerned, Dark Souls (FromSoftware 2011), or any

Soulsborne for that matter, also falls within the environmental narrative. The

game relies on its strong level design that put an emphasis on a well-organized

world; the players create connections between different areas «that

display distinctive tint, enabling [the players] to easily recognize them and

associate a name to a color» (Gamekult 2018, my translation). At the same

time, the game also uses basic script narrative elements: every item's

description contains a glimpse of narrative, cleverly places next to the item's

effect that players will eventually seek out.

The goal here was not to try to list every type of narrative

there is, but to illustrate the idea that video games possess many tools for

storytelling purposes, that embrace the medium capacity to stir together

several art field. Accordingly, their means of conveying «messages»

to players are quite large, and expanded even further by the fact that the said

players interact with them. In that sense, the premise of my research is that

every game is narrative in its own specific way.

4 One of the problems with procedural can be the

complete absence of fixed design, whether it is the world or its characters. In

No Man's Sky case, it resulted a severe lack of coherence, especially with the

wildlife.

25

Player's agency: to interact or not

When we talk about narrative ability, we usually mean

storytelling in the broad sense: a story that is told to us. However, video

games do not necessarily aim at telling any sort of story; in the medium's

early days, one could say it was not even considered, as we observe Space

Invaders (Taito, 1978), Pac-Man (Namco, 1980) or Pong

(Atari, 1972). Nowadays, there are still numerous titles that have no

intention to relate a story properly speaking: Rocket League (Psyonix

2015), Fortnite Battle Royale (Epic Games 2017) or Minecraft

(Mojang Studios 2011) to name but those three, are all about the

«immediate» experience, thus not bothering themselves with specific

plots. Although they also use narrative devices, the story mostly forms through

the player's own experience.

In his essay «La narrativité vidéoludique:

une question narratologique,» Marc Marti explores the relation between the

game and the player through narratives:

Empirically, video games are therefore both based on a

static, pre-established and scripted narrativity, and a dynamic storytelling

produced by the player interaction with the game. The combination of the two is

what constitutes video game narrativity [...] As narratologist, we postulated

that video games always had a narrative basis, but at various degrees (Marti

2014, 12, my translation).

In a media that involves interactivity, storytelling operates

differently from «traditional» media--like books or movies. Game

narratives must take the player into account, in other words, the fact that the

game's story progress with the player input--the amount of interactivity

influences how narrative elements are set. That tension between interactivity

and narratives grants agency5 to the players that allow them to

become storytellers themselves. That is also why the definition I exposed

earlier for narrative was a bit off the mark. Video games, though they can

perfectly use narrative to convey a particular story, are also able to simply

deliver the groundwork for the players to make their own.

The case of Minecraft can provide insights in that

regard. The game is very simple: a giant sandbox in which you can build your

own world with (almost) no limitation but your imagination. Although there are

things to explore, there are no quests, no characters (besides

5 Agency is the degree to which a player is able to

cause significant change in a game world (What Games Are,

https://www.whatgamesare.com/agency.html#:~:text=Agency%20is%20the%20degree%20to,the%20world%20

with%20every%20action). In other worlds, agency represents the differences

the player can make when interacting with a game.

26

you) and, of course, no pre-established plots. Minecraft

puts the player in an environment where they are by themselves from the

beginning and have to exploit their own creativity to survive -- depending on

the mode they are playing--and craft their world.

In his essay «Minecraft and the Building Block of

Creative Individuality,» Josef Nguyen assimilates Minecraft to island

narratives, arguing that the isolated geography entails the player's creativity

through a simulation of «Crusoe's Island»:

Minecraft participates in an enduring narrative

tradition that deploys the island, or similarly isolated geography, as the

experimental setting to negotiate tensions between the individual and the

social in the development of creative subjects [...] Minecraft and its

two primary playing modes--Creative and Survival--enable players to experiment

with various environmental and sociopolitical conditions imagined in island

narratives (Nguyen, 2016).

By being in an isolated environment, the player, thus in

total autonomy, experiment as an «inventive subject». They create

«their own social and environmental conditions»: the narrative

aspects of the game become solely their own, build over time with their world,

along with the numerous events that occur in between--the basis of what we

named above emergent narrative. The player fashion their story through

playing.

The key point here is the agency given to players. In the

case of Minecraft, they can shape the world as they see fit: they hold

the reins throughout the entire course of their play session. Henceforth, with

full agency for the players, the game loses part of its ability to be the

storyteller itself. It then relies more on indirect form of storytelling

(mainly environmental) set by its world building. This particular tension

between games and players, where one forfeits their role as a storyteller over

the other, is explored by Sky Larell Anderson in his study:

Agency to tell a story oscillates between the storyteller--in

this instance, a game--and the interactive participants--namely, the players.

The more agency that interactants possess, the less agency the storyteller has

to construct the narrative. (Anderson, 2018)

Conversely, story-driven games intentionally limit players'

capacity to interact within their worlds, with the object of keeping them

invested with the narrative arc. Hence the use of cutscenes, which deprive the

players of any interactive capability; they interrupt the gameplay in order to

provide narrative contents that they cannot alter.

The same idea lies behind particular sequence that wants the

player to feel and contemplate instead of playing. A remarkable scene in

NieR: Automata illustrates my point quite well. After hours and hours

playing as the android 2B, one of the three main characters, a

27

virus infects you and corrupts your system. Slowly, you lose

the abilities you had enjoyed since the beginning: your screen glitches more

and more, you become unable to even run but still have to try to avoid enemies;

at some point, you can only see in black and white. Ultimately, you cannot play

at all: your character stops moving which led to cinematic that marks the end

of the game as 2B.

The whole objective behind that memorable and powerful scene

was a deep emotional engagement from the player, by taking away what they

thought was granted. As they lose their power of interaction, cleverly

displayed by the game in a step-by-step process, they steadily start to play

without actually playing. One can see it as a sort of narrative break meant to

involve players in a specific sequence of events, without completely cutting

them off from the game like a cutscene (Fregonese, 100). The tension between

interactivity and narrative unbalances itself in favor of the latter. The

interactivity gradually becomes «fake»: though players can still act,

they are only given the illusion that they are still control.

Some scholars like Sebastian Domsch refer to this feature as

«event trigger.» Players, by performing a specific action--usually

spatial movement--trigger a «narrative relevant event»:

Most often, the trigger is connected to the player

character's spatial movement, that is, an event is triggered when the player

character enters a specific space. The event itself is a scripted sequence, but

in contrast to a cut-scene it happens within navigable space and without an

interruption to gameplay time [...] The design is to create the impression that

an event happens by chance, though usually exactly at the narratively and

dramatically relevant moment. [...] While many game design features attempt to

create the illusion of agency where there is none, event triggers are largely

used to veil the fact that the player actually does have agency over the

happening or not happening of a specific event, while at the same time hiding

the fact that the event is in no way contingent, but determined. (Domsch,

41)

More than just taking away players' control, an event trigger

creates the illusion that they still have it. In Nier: Automata's

example, you actually can move until the last seconds of the event, yet

your actions cannot change the outcome: the character's death. The players are

still in a state where interaction is permitted--unlike with a cutscene--but

the denouement actually happens through a narrative straight line.

Event triggers address some of the problems that a game

encounters when it seeks to communicate narrative events from the gameplay

standpoint. In his study, Cheng Paul explains the need for games to

«balance the delivery of narrative information against the notion of

player agency» (Cheng 2007, 21). Because for a story to be unfolded, game

designers need specific

28

actions from the players. The agency provides players with a

certain margin of actions, they de facto «don't always do what designers

need or want them to do.» That is the core idea behind cut-scenes: remove

their agency (their access to the game's interface) to advance the game's

narrative. But the mere use of cut-scenes raises another problem which is the

passivity it induces; though it is often perceived as reward upon achieving a

meaningful action, an overabundance of cut-scenes or wrongly placed ones can

break a game's rhythm and build up players' frustration over their deteriorated

experience. Event triggers spare the game's pacing from being unnaturally

altered, while at the same time «guarantee that the players actually get

to experience events without feeling that they are forced to do» (Domsch

2013, 42).

Eventually, video games rhetoric works around the agency

given to the player. The designers structure the storytelling and the whole

story into interactivity either for the player to unfold the events through

their actions (Piccuci 2014) or to create their own. In any case, there is a

«dialogue» between the designers and the player that form the overall

narratives. Exploring a game through this perspective, we are able to

comprehend the basis behind the story delivery.

B- Hades, a story to die for

Again, narrative design in video games is all about cleverly

blending the narrative ropes within the gameplay to shape a coherent and

meaningful experience for the player. Story and plot unfold following player's

progression; in other words, narration in video games is «a collaborative

act between game designers and players» (Picucci 2014). Hades

represents a perfect example to explore that dynamic. Its affiliation to

the roguelite genre induces the use of a specific storytelling process,

delivering a storyline imbedded in a «loop» where player's failure is

expected. In other terms, Supergiant Games' title emphasizes the procedural

rhetoric, a concept coined by Ian Bogost that describes how "rhetoric functions

uniquely" in video games and defines it as such:

I call this new form procedural rhetoric, the art of

persuasion through rule-based representations and interactions rather than the

spoken word, writing, images, or moving pictures. This type of persuasion is

tied to the core affordances of the computer: computers run processes, they

execute calculations and rule-based symbolic manipulations [...] More

specifically, procedural rhetoric is the practice of persuading through

processes in general and computational processes in particular. Just as verbal

rhetoric is useful for both the orator and the audience, and just as written

rhetoric is useful for both the writer and the reader, so procedural rhetoric

is useful for both the programmer and the user, the game designer and the

player. (Bogost 2007, preface IX, 3).

29

Procedural rhetoric designates video games' capacity to tell a

story through repeated processes and interactions, to create the tale from the

gameplay. As underlined by Fregonese , this specific rhetoric can be "applied

by emphasizing on success or failure, obedience or disobedience" (Fregonese

2017, 84, my translation).

Hades purposely relies on its gameplay loop to

create a narrative tension: success and failure both intertwine with the story.

The player must repeat a specific process which further unfold the story each

time. My intents here is to investigate this particular relation between

gameplay and the narratives, and the place of the player in it. Moreover, we

will determine the roguelite's code, and how they were transposed as narrative

tools in the game. Then we will analyze the main character of the game, his

reflection of the player's experience, before focusing on the methods used by

the studio to ensure the narrative continuity.

Death as a narrative feature: Hades, the

roguelite

Hades was created by Supergiant Games and launched

on September, 2020. As displays on the game's Steam page6, the game

is a roguelite, action-RPG, dungeon crawler, where you take control of Zagreus,

son of Hades, and attempt to escape the Underworld. To do so, you get help by

the gods of Olympus who grants you various power-ups.

Before going any further, we have to properly define

roguelite, since the game essentially revolves around that component. In the

first place, genres in video games are hardly normalized; they always change

over time, never to have conventions set in stone. That is not to say they

cannot be defined; however, their definition sustains some porosity over one's

subjective experience--which is why the displayed genres for a game tend to

change from one video game platform to another8. Genres serve to

create expectations over specific elements for the players. With this in mind,

I have no intention to impose my definition; the goal here consists in the

extraction of a roguelite's main characteristics and what the label entails.

6

https://store.steampowered.com/app/1145360/Hades/

8 For instance, while Hades is labeled as

an action roguelite on Steam, it is only referred as action RPG on the Epic

Games Store

https://store.epicgames.com/en-US/p/hades?lang=en-US

30

Roguelite derive from roguelike, an RPG subgenre named after

the 1980's game Rogue, and share most of its characteristics. In 2008,

roguelikes were attributed specific factors at the International Roguelike

Development Conference. The conference's attendants defined Roguelikes with

what is known as the Berlin Interpretation:

· Procedural generation of the game world: the stages,

items and placement of enemies are random.

· Crucial management of resources such as health point

and gold, in order to survive as long as possible.

· Game uniformly grid-based. Whether it is the player or

the enemy, each occupies a predictable space (a tile).

· The game is non-modal: every action (movement,

combats, etc.) takes place in the same mode

· Turn-based game: each command is attributed to a

single action or movement. There is no time limit to perform an action.

· A punishment system (usually permadeath) that forces

the player to start again at the beginning every time they die or fail the

objective.

· Layers of complexity that allow several solutions to a

single objective.

· The player is compelled to conduct careful exploration

and discover usage of unidentified items, which has to be done anew every

time.

· A Hack'n Slash game where it is the player vs the

game's world. The player has no other option but to kill every enemy they

encounter.

The agreed factors listed above were but «an attempt to

define the parameters of the genre» (Brewer 2020). Roguelikes at the time

did not necessarily check all the boxes and today's games labelled as such

certainly do not either. Dead Cells (Motion Twin, 2018), Risk of

Rain 2 (Hopoo Games, 2020) and Neon Abyss (Veewo Games, 2020) all

display the tag «Roguelike» on their Steam Page, while being neither

turn nor grid-based. The genre now largely exceeds the frame of the Berlin

Interpretation, which was already porous to begin with. Which is why

RogueBasin, a community website entirely dedicated to roguelikes, provides a

distinction between roguelikes and «traditional roguelikes». The

latter which refers to games «with a strong focus on Intricate gameplay

and replayability», an «indefinite amount of time» for the

player to «make

31

a move», and «provides new content and challenges on

every run» in an «abstract world representation using characters or

simple sprites» (RogueBasin).

Most of the recent roguelike games are easily distinguished

from traditional ones. Still, they undoubtably uses some of their core designs,

notably the gameplay «loop» generated by the «permadeath

system», the randomization of specific features and the management of

resources, and a challenging experience. The combination of these elements

creates a «die and retry» aspect; replayability is thus a high-value

factor, since players are entailed to replay the game in order to complete

it.

Back to roguelite, this appellation designates an evolution

that toned down some of the Roguelike designs, such as the

«permadeath» which is not a complete restart anymore. Roguelite game

are «colloquially known to feature certain elements of roguelikes, but

presented in a more user-friendly fashion» (Brewer, 2020). A roguelite

game displays a more forgiving game design, in the form of a meta-progression:

even though «permanent» death remains a core element, the reset it

ensues is not total and you still retain persistent abilities, items or

upgrades that make your next attempt at clearing the game easier. You never

truly restart form zero.

So, while Hades falls in the «commonly

accepted» roguelike genre - failure does mean restarting the game - it is

considered a roguelite game since the player undergoes a progression: weapons

can be upgraded, deepened relations with Olympus gods give access to more

powerful boons, some resources unlock permanent perks, etc. I chose here to

make the distinction, because the meta-progression is in fact the core of

Hades. A major part of the game's world is built up using this

feature; above all, the meta-progression is used as a storytelling tool.

During my research, I took an interest in finding what made

Hades a success. One of the reasons was because the game is referred

as a roguelike, a genre that, all in all tend to discourage numerous players

due to how challenging it can be. Hades is certainly not the first

roguelite (or roguelike) to meet with success: The Binding of Isaac

(McMillen & Himsl, 2011), Dead Cells and Into the Breach

(Subset Games, 2018) among others are occurrences of roguelike that

managed to do it too. Nevertheless, Hades seems to have had a stronger

attraction on players that usually dislike this kind of games: When I went over

the Steam review page dedicated to the game9, I noticed

numerous players stating that they enjoyed the game despite having trouble with

other roguelikes. In one player's review, we can read «Whilst I'm not a

fan of these roguelikes, permadeath games usually, I have to say I'm very

impressed with this game; others

9 Hades's steam review page:

https://steamcommunity.com/app/1145360/reviews/?p=1&browsefilter=toprated

32

wrote that they were «not one to play games in this style

usually, but immediately took to Hades» or that it was their

«first roguelike that [they] actually enjoyed.»

While it is not unusual to observe such comment in players'

game review, it did occur a lot in this case. So, I also examined the reasons

Hades won over those players and what emerged the most was «how

good the story was» with the narratives skillfully interlocked with the

gameplay and the progression.» Most of the Press reviews also underlined

those design elements. Gamestop's review stated that «the way story and

gameplay intertwine makes Hades a standout roguelite» (Vazquez 2020). In

the Gamekult's review, Gauthier Andres «Gautoz» states that all in

all, the game is all about its story:

It is the narratives that makes the [game's] world go round.

We live and die for the new weapons, the gods' boons and the fresh cosmetics,

but we fight for the story. Every fiber of that reinvented mythology and every

intimate secret between two capricious gods is snatched by the arrow and the

sword. Then, they come to feed a thick fabric of theories, characters to fully

develop, relationships and surprises lovely prepared by the designers (Gautoz,

2018, my translation).

Not only the story is what Hades focused on, but it

makes sure that every detail about the plot, the characters and the world are

to be accessed through the gameplay - the story unfolds with each attempt at

clearing the game, whether the player fails or not.

It appears then Hades's storytelling is what made

the game particularly appreciated; not just for the story itself but for the

skillfull merging of clear narratives and the roguelite genre that

conventionally does not put story and plot in the spotlight. Hades

makes its world and story shine in a genre where it is not expected.

To hell and back again: playing the game, exploring

the tale

The main character, Zagreus, is determined to leave his

father's domain and go to the outside world, not only because he wishes to be

free of Hades but also because he intends to find Persephone, his birth mother

whom he never knew. Along the way, the gods of Olympus send him messages and

power-ups, for they are eager to see him escape and join them. Unfortunately,

Zagreus's endeavor always ends with him dragging himself out of the pool of

blood [Figure 1], only to try again. Because even when he manages to get out,

he cannot live

33

on the surface but for a short amount of time. Whether Zagreus

dies or manages to get out of the Underworld, he always returns to the starting

point.

Figure 1 - Hades, the

pool of blood that symbolizes both the beginning and the end of the game.

Strictly speaking, each player's run is doomed from the

start. They are stuck in a loop they cannot broken out: whether they clear the

game triggers a reset that entails the player to do it all over again. But for

a game to keep the player playing in those circumstances, it needs to stimulate

its replayability - the basis for a roguelike/lite game. I argue here that what

compels the player to continually engage in Hades is the multitude of

narratives ropes and all they involve.

Supergiant Games earned its renown for its strong focus on

narrative games; their modus operandi is to work «narrative and themes

from the start» and not just create «a story and backsolve the

gameplay onto it» (GDC 2021), for the sake of a good harmony between

design, themes and story. On the GDC podcast, Creg Kasavin explains how they

came up with Hades, their thought process behind its storytelling:

Our mindset was «can we use this genre format to tell a

story?» and a thing I would think about often is, even in the hardest core

roguelike game, where it resets you completely to nothing from one playthrough

to another, there is in fact something that you carry forward which is your

knowledge of the mechanics in the game. Using your knowledge, you can get

farther and farther. So, it was a fun thought exercise to think of a game

premise where the character had the same ability. So, it leads you to

«what sort of character would still remember what happened after they die?

What about a character who's just immortal?

34

Surely, when we stated earlier that the permadeath system in

roguelikes was a complete reset of the game, we could say that it is not

entirely true. In each attempt at beating the game, the player gather

knowledge, whether it is enemies' patterns, position of traps and secrets that

allow them to do better the next time. It follows the die and retry principle

(or «trial and error»), a gameplay mechanic for which the player is

expected to use their death to choose a better course of action afterwards. The

Soulsborne series of FromSoftware for instance is designed around it: the

player is expected to die many times, but also to learn from their failure and

overcome the obstacles. In essence, die and retry can be observed in the

majority of video games, and represent a deep-rooted feature the medium evolved

around. As Jesper Juul said, «we experience failure when playing

games» (Juul 2005, 2), and above all, «it is the threat of failure

that gives us something to do in the first place» (ibid, 45). Supergiant

Games applied this principle directly to Zagreus, whose condition (son of a

god) allows him to «defy» death: like the player, he experiences

failure and acquires knowledge from it, and becomes stronger little by

little.

Zagreus is a character that mirrors the player: both of them

are fully aware of the fate that awaits them upon reaching the surface/beating

the game, but still choose to pursue their doomed endeavor. One character in

particular embodies the meaning behind Zagreus and the player's action:

Sisyphus [Figure 2]. Like all the others in the game, Sisyphus is an existing

character in the Greek mythology. His myth portrays him as the most astute

among men, who cheated death not once but twice by deceiving both Thanatos, God

and personification of death, and Hades. For his defiance, Sisyphus was

punished and forced to push a giant boulder up a hill for eternity, as it would

bring him back down every time, he would reach the top.

In Hades, Zagreus can encounter Sisyphus,

accompanied by Bouldy (the famous boulder) [Figure 3] in the first part of the

underworld; their discussions, I believe, exposes the philosophical meaning

behind the game, should we talk about Zagreus's story or the player's

experience. Indeed, in the same manner Sisyphus falls all the way down the hill

after he reaches its top, Zagreus (and the player) always ends up in the pool

of blood at Hades's chamber. Even what can be considered as the game's

ending--the culmination of the main story at least-- Zagreus slowly goes back

to the underworld during the credits. Then again, he is asked to

35

continue his escapes, under the pretense of testing Hades'

realm security and upholding the gods' expectation towards him and distract

them.

Figure 2 - Hades, Sysyphus the

tortured soul, an NPC encounter in Tartarus.

Figure 3 - Hades, Bouldy, the boulder

that Sisyphus has to continuously push up a hill.

36

As bleak as it sounds, Zagreus and the player willfully accept

their task, because their quest is not fruitless. Like I have said above, the

story unfolds for each break out and the main plot reveals itself whenever the

player succeeds. The repetitive and supposedly futile endeavor is a central

part of the narrative. Through narrative the player finds commitment; they

embrace the inevitability of enacting the same venture again and again. And it

is not solely about the main plot: as the player wanders through the

underworld, they encounter various characters. For each time they cross their

path, talk to them or offer them gifts, they deepen the relationship between

them and Zagreus. Hence, the player learns more about the game's world while

Zagreus forms connections with those characters. The overall development

represents meaning: each escape attempt allows the player to strengthen those

connections and in a more utilitarian aspect, offers them acquisition such as

legendary weapons that bring new layers of gameplay.

In that sense, enjoyment of the game «comes less from

winning and more from just embracing each new attempt» (Alexander 2021).

Whilst the roguelite's death mechanic create a tension between the narratives

and the player's goal of clearing the game, narratives and gameplay blend

together for the player to enjoy the experience outside of their goal. Along

their many escapes, the player uses distinct weapons with several gameplay

variations - each of the 6 weapons possess 4 forms - discover gods' boons

combinations, secrets, and collect resources to further strengthen Zagreus or

unlock new features. A multitude of elements is consequently used as narrative

features, since they all make their contributions to the world and character

building - weapons for instance belongs to gods or mythological heroes who will

take notice of you wielding them.

The son of Hades himself displays his overall enjoyment of

the situation. With the tedious and madly repetitive task ahead of him, Zagreus

nonetheless shows merriment . Once again, we can draw a parallel between him

and Sisyphus. In Wisecrack's podcast «The philosophy of Hades», Dr.

Kristopher Alexander assimilate Hades's Sisyphus to the one described

in the philosophical essay «Le Mythe de Sisyphe», by French writer

Albert Camus. He points out the absurdity of Sisyphus' task, but despite that

eternal chore, Sisyphus fully accept his condition as shown in [] and in

«his acceptance, he finds contentment, happily going about his task

without ever expecting to achieve anything by it»(Alexander 2021). Indeed,

Albert Camus, largely known for his work on absurdism, describes the

pointlessness of Sisyphus goal to reach the hill - since he is bound to be

dragged down to the bottom - but also that he finds joy in it. Happiness can be

found in the meaningless:

37

Sisyphus silent joy is here. His fate belongs to him. His

boulder is his thing. Likewise, when he contemplates his torments, the absurd

man silences all of the idols [...] I let Sisyphus at the bottom of the

mountain! One can still find his burden. But Sisyphus teaches superior fidelity

that denies the gods and lift the boulders. He too judges that all is fine.

This universe, from now on without master, does not seem futile nor pointless.

All the pieces of this rock, all the mineral shards from the mountain full of

night, all forms a world. The struggle to reach the top is itself enough the

fill a man's heart. One needs to imagine Sisyphus happy (Camus 1942, 94, my

translation).

Even though this is a philosophical approach, it is

interesting to see that Sisyphus mirrors Zagreus's endeavor, and by extension,

that of the player. The latter goes through the same areas and fights the same

foes over and over; as they become accustomed to the task, they progress

further on, until they reach `the top.' The whole endeavor becomes a force of

habit that is executed better each attempt, thus stemming satisfaction. The

player can then continue to enjoy the struggle by making the task harder--a

self-imposed difficulty with the game's heat system--and reenacting the whole

process. Whilst the difference between Sisyphus and the player lies on the fact

that the consecration of the plot and the story development as a whole serve as

meaning, it is also true that those factors are here to induce the player to

engage in a repetitive task.

It surely demonstrates Supergiant Games's intention to

embrace the roguelite genre while giving the player a true narrative

experience; narratives and gameplay respond to each other in a game that is but

an unbreakable loop. A loop that nonetheless keep the player engaged through a

narrative continuity, as explained by Greg Kasavin:

We are always trying to align the player experience with the

narrative and it leads to having a character like Zagreus who can be serious

one moment, self-deprecating another. Even though he has a lot of personality

on his own, in some ways he is there to so to speak for the players' experience

and just try to find that connection between the player's experience and the

story. So, it all kinds of flowed from there, that idea «what if there was

a Rogue Like with narrative continuity where every time you run into a boss,

they remember you. You start keeping track who won this time, who won last

time; it was fun to think about that as a starting point (Kasavin 2021).

The more Zagreus tries to leave the Underworld, the more he

becomes acquainted with the ones guarding it. Each encounter with the bosses

offers pieces of interaction between them and Zagreus. Upon defeating the

second boss of the game (The Bone Hydra) a certain number of times, Zagreus

decides to nickname it «Lernie». Further on, the name is also for the

player to see, indicated above the boss's health bar and on the post-victory

screen [Figure 4]. It adds a sense of unity for the whole game: the player is

still in the loop, but the game's world

38

acknowledges it. Zagreus' relationship with NPCs is not

limited to «friends» but also concern some enemies, who remember

being defeated by him (or not). The first boss Megaera, for instance, can be

talked to afterwards, and the relation may evolve into a romance depending on

the player's choice.

Figure 4 - Hades, The Bone Hydra,

second boss of the game. It is named Lernie after a few confrontations against

Zagreus.

At every turn the game seems to have something to say, even

after the 100th run. Yet, it is very hard to witness a character

that would repeat the same dialogue. That is to say, past the 70 hours into the

game, they are still information and elements about the game world for the

player to look for. The narrative cohesion is a central preoccupation for the

game, it makes sure that the player stays on track with the world building

regardless of how long they play the game. The interactions with the numerous

characters are by no means unlimited, but the pace of the story almost entirely

hides away those limits. As underlined by Gene Park in his article for The

Washington Post, Supergiant Games «limited interaction to maintain

narrative cohesion and immersion» (Park 2020). They made sure that the

player would have a sense of progression, which is why they «can never

talk to another character more than once per return visit» (ibid). It

ascertains the replay value.

39

Again, Hades is the perfect specimen to observe the

narrative relation maintain between the game and the player. The act of play

generates a narrative tension which compels the player to progress through the

game, and thus enact the replayability. Roguelite games are certainly not known

for that kind of storytelling. Narratives in those games are usually more

cryptic, if not hidden away from the player or delivered piece by piece through

fragmented texts and environmental narrative, as in Dead Cells.