|

Submitted at Freising, September 30, 2021

Technical University of Munich

The Role of Financial Institutions in

Value Chain Finance in the Global

South

Scientific work to obtain the degree

M.Sc. Agrarmanagement

At the Chair Group Agricultural Production and Resource Economics

of the TUM School of

Life Sciences.

Supervisors M.Sc. Roberto Villalba Camacho

Chair Group Agricultural Production and Resource Economics

M.Sc.Terese Venus

Chair Group Agricultural Production and Resource Economics

Examiner Prof. Dr. agr. Johannes Sauer

Chair Group Agricultural Production and Resource Economics

Submitted by Moahmed Ali Trabelsi

Matrikelnummer: 03703889

Giggenhausser str. 2985354, Freising +4915221671931

Declaration of authorship

I, Mohamed Ali Trabelsi, born in Tunis, Tunisia, with

matriculation number 03703889; declare that this thesis and the work presented

in it are my own. It has been generated as the result of my own original

research on the subject «The Role of Financial Institutions in Value Chain

Finance in the Global South»

I confirm that:

ü This work was done wholly in candidature for MSc

degree thesis fulfillment at the Technical University of Munich.

ü Where I have consulted published work of others, that

was always clearly credited.

ü Where I have taken some ideas from other sources, I

have mentioned the sources and except these kinds of quotes, the entire work is

mine.

Date 30.09.2021 Signature:

i

Table of Contents

Table of Contents ii

List of Figures v

List of Tables vi

List of Abbreviations vii

Acknowledgment viii

Abstract ix

1. Introduction 1

1.1. Problem statement 1

1.2. Objectives 2

1.3. Research questions and hypothesis 2

1.4. Expected results from the research 3

1.5. Organization of the thesis 3

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Background 4

2.1. Agriculture finance 4

2.1.1. Agricultural credit 4

2.1.2. Financial institutions (FIs) in the Agriculture Sector

6

2.1.3. Microfinance 7

2.2. AVCF definition 9

2.3. AVCF Challenges 11

2.4. Competitiveness of agricultural finance 14

2.5. Determinants of agricultural credit 17

2.6. Literature on AVCF 19

2.6.1. Gap of the Literature on AVCF 19

2.6.2. Available literature on AVCF 20

3. Methodology and Data 22

3.1. Description of the study 22

3.2. Building the database 23

3.3. Statistical Analyses 25

3.3.1. Qualitative Analyses: 25

3.3.2. Quantitative Analyses 25

3.3.3. Cluster Analysis 26

3.3.4. Data Types and Variables 27

3.3.5. Other components of the database 30

3.4. Structure of survey 30

ii

3.5. Sample Design 31

3.5.1. Sampling frame 31

3.5.2. Sampling techniques 32

3.5.3. FIs Listing: 33

4. Survey Design and Conceptual Framework 34

4.1. Exploring other surveys 34

4.1.1. Survey with FIs 34

4.1.2. Survey with farmers (World Bank & CGAP) 35

4.1.3. Integrated Financing for Value Chains (WOCCU) 37

4.1.4. Survey on national development bank (World Bank Group)

37

4.2. Credit Scoring for Agricultural Loans 38

4.3. Financial instruments employed by FIs 40

4.4. Survey design for FIs officials 41

4.4.1. General Information 42

4.4.2. Economic information 42

4.4.3. Credit screening, scoring, and monitoring for

Agricultural loans 42

4.4.4. Agricultural finance within value chains 43

4.4.5. Financial product & Instrument employed 43

4.5. Overview of the online questionnaire 43

5. Analysis and Results 45

5.1. Descriptive Analysis: 45

5.1.1. Geographic distribution: 45

5.1.2. Distribution by institutional type: 45

5.1.3. Foundation Year: 46

5.1.4. Number of Branches 47

5.1.5. Agricultural loans 47

5.1.6. Gender Equality 48

5.1.7. Digital Solutions 49

5.2. Cluster Analysis 50

5.2.1. Confirm Data: 50

5.2.2. Scale the data 51

5.2.3. Select segmentation variables 51

5.2.4. Define similarity measure: 51

5.2.5. Number of clusters 51

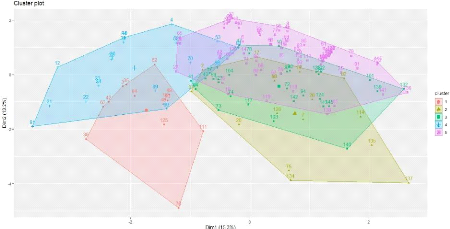

5.2.6. K-means Clustering Method 52

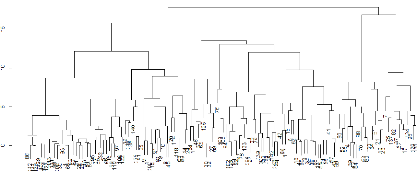

5.2.7. Hierarchical Clustering Method 54

5.2.8. Selected method and number of clusters 55

iii

5.2.9. Extracting Results 57

6. Discussion 62

6.1. An information provider database 62

6.2. Analysis of the clustering analysis 63

6.3. Limitations and further research needs 64

7. Conclusion and Recommendations 67

7.1. Conclusion 67

7.2. Recommendations 68

References 70

Annex A I

Annex B: Database II

Annex C: Survey for FIs Officials IX

Annex D: R Script XVI

iv

v

List of Figures

Figure 1: Sources of agriculture credit 5

Figure 2: Components of direct and indirect agriculture credit

6

Figure 3: Development Process through Micro-finance 7

Figure 4: Overview of value chain finance Triangle 10

Figure 5: Considered factors to reduce TC and risk management

in agricultural finance 15

Figure 6: Geographical location of the financial institutions

22

Figure 7: Geographical distribution of financial institutions

32

Figure 8: Listing criteria of financial institutions in the

final database 33

Figure 9: Financial institutions Questionnaire components

41

Figure 10: List of instruments enquired during the survey

43

Figure 11: Questionnaire Framework 44

Figure 12: Determination of the optimum number of clusters

52

Figure 13: Grouping Data scaled in different clusters 53

Figure 14: Clusters Visualization 53

Figure 15: Hierarchical Clustering 54

Figure 16: Validation of the number of clusters 57

vi

List of Tables

Table 1: Distribution of MFIs by institutional type 8

Table 2: The challenges of the agriculture finance according

to the literature review 12

Table 3: Determinants of credit Access 19

Table 4: Number of FIs mentioned in the literature review

21

Table 5: Composition of database 24

Table 6: Most popular Qualitative Analysis method 25

Table 7: Quantitative statistic types 26

Table 8: Data types 27

Table 9: Continent Attributes 27

Table 10: Institutional Type Attributes 27

Table 11: Agricultural loans Attributes 28

Table 12: Gender Attributes 28

Table 13: Digital Solutions Attributes 29

Table 14: financial Institutions General Information 34

Table 15: Specific loan features 35

Table 16: focal points of the World Bank Survey 36

Table 17: Lending decision variables 39

Table 18: Loan accreditation Characteristics 40

Table 19: AVCF Instrument 40

Table 20: Classification of financial institutions by

continent 45

Table 21: Classification of financial institutions by

institutional type 46

Table 22: classification of financial institutions by

foundation year 47

Table 23: Classification of financial institutions according

to the number of branches 47

Table 24: Percentage of credit offered by type of financial

institution 48

Table 25: Percentage of gender equality program offered by

type of financial institution 49

Table 26: Percentage of digital solutions offered by type of

financial institution 49

Table 27: Descriptive statistics of the dataset 50

Table 28: Cluster membership IDs using K means method 54

Table 29: Cluster membership IDs using Hierarchical method

55

Table 30: Nomination of the FIs groups 57

Table 31: Cluster's characteristics 60

List of Abbreviations

vii

ADB Asian Development Bank

AFD Agence française de développement

AfDB African development Bank

AFRACA African Rural and Agricultural Credit Association

AL1 Farmer credit

AL2 Agribusiness Credit

AOI Agriculture orientation index

AVCF Agricultural value chain finance

CB commercial banks

CGAP Consultative Group to Assist the Poor

DBs Development Banks

DS1 Online Banking

DS2 E-products Email and SMS Banking

DS3 Online loan application

FI Financial institution

G1 Credit facility for women

G2 Career development opportunities to female staff

G3 Gender Programmes

GS Global South

IDFC International Development Finance Club

IFAD International Fund for Agricultural Development

IFC International Finance Corporation

IFI International financial institutions

IIRR International Institute of Rural Reconstruction

INSE Institute of New Structural Economics at Peking

University

ISF advisory group

KIT Royal Tropical Institute

MBFI membership-based financial institutions

MFCs microfinance Companies

TC transaction costs

VC value chain

VCF value chain finance

WFDFI World Federation of Development Financing

Institutions

WBG World Bank Group

WOCCU World council of credit unions

Acknowledgment

VIII

The first thing I want to say is how grateful I am to God and

my father for the opportunity to study at the Technical University of Munich. I

would also like to extend my deepest gratitude to my sister Emna for her

support throughout the entire thesis process. Also, I want to thank my

girlfriend Myriam, as well as my friends Anas, Christian, Cyrine, Dali, Mourad,

Rached, Ramzi, Sabrina, Safa, Youssef, Wajih, Werner, and Zeineb for their

continued encouragement.

My thanks go out to Villalba Camacho Roberto and Venus Terese

for their helpful guidance and valuable comments and corrections during this

work. This work cannot be done without them. My strong gratitude to Susanne

Minges and Papaja-Hülsbergen Susanne for their continuous support during

my studies at TUM.

The internship opportunity with Agribusiness Facility for

Africa (ABF) and Green Innovation Centres for the Agriculture and Food Sector

(GIC) at the GIZ was a big milestone in my career development. It was a great

chance for learning and applying my knowledge and fresh skills in a real

working setting. I will strive to use everything I learned in the best possible

way. Through this internship, I met wonderful people and professionals who

helped me develop my experience. I would like to express my deepest thanks to

Dr. Annemarie Mathess, Carsten Schüttel, Wahid Marouani, and Melanie

Hinderer for their guidance and allowing me to participate in their projects

which helped me expand our knowledge on various topics.

ix

Abstract

Small-scale farmers and agribusinesses in the Global South

still face many barriers to access credit, despite the efforts of development

agencies, facilitator, and even financial institutions. An agricultural gap

persists that limits sector potential. The current master's thesis examines the

ways in which financial institutions make credit easier to obtain for

smallholder farmers and value chain players. The study uses a unique database

of 347 financial institutions in 106 countries from Africa, Asia, South

America, and Oceania as well as international institutions. It primarily

contains cooperatives, commercial banks, NGOs, microfinance institutions, and

agricultural banks. The database is constructed through a snowball effect

process using literature sources, online search, and open-source bank

platforms. This database contains several details about these institutions

including their institutional type, agricultural loans, gender equality, and

digital solutions.

The number of financial institutions was reduced to 144 for

the statistical analysis due to the lack of available data for several

financial institutions. Then an analysis of clusters was conducted to answer

the research question and determine patterns, similarities, and differences

among the selected financial institutions. Five clusters were identified. It

emerges from the study that financial institutions deliver customized and

enhanced rural financial services in high demand and in line with gender

issues, as proved in clusters 1, 2, and 3. Moreover, the youngest group of

institutions is cluster 4, which has the most digital solutions to offer.

Cluster five, which contains individuals primarily using traditional banking

methods, has the lowest level of financial services. This study has addressed

the research question in terms of credit provision, gender promotion, and

digital solutions, as well as identified the kind of similarities and

differences between financial institutions. Several recommendations are made in

this study, including the need to encourage women and provide digital solutions

to ease the lending process for small-scale farmers and value chain actors.

Keywords: Agricultural Value Chain Finance, financial

institutions, cluster analysis, financial products, Global South

x

Zusammenfassung

Kleinbauern und Agrarunternehmen im globalen Süden sehen

sich trotz der Bemühungen von Entwicklungsorganisationen, Vermittlern,

Maklern und sogar Finanzinstituten immer noch vielen Hindernissen beim Zugang

zu Krediten gegenüber. Es besteht weiterhin eine Lücke in der

Landwirtschaft, die das Potenzial des Sektors einschränkt. In der

vorliegenden Masterarbeit wird untersucht, wie Finanzinstitute Kleinbauern und

Akteuren der Wertschöpfungskette den Zugang zu Krediten erleichtern

können. Die Studie stützt sich auf eine einzigartige Datenbank von

Finanzinstituten in 106 Ländern Afrikas, Asiens, Südamerikas und

Ozeaniens sowie von internationalen Institutionen. Sie enthält vor allem

Verbände, Geschäftsbanken, NGOs, Mikrofinanzinstitute und

Landwirtschaftsbanken. Die Datenbank wurde in einem Schneeballeffekt-Verfahren

unter Verwendung von Literaturquellen, Internetrecherchen und

Open-Source-Bankenplattformen erstellt. Die Datenbank enthält verschiedene

Details über diese Institutionen, darunter ihre institutionelle

Einrichtung, Agrarkreditangebote, Frauenförderung und digitale

Lösungen.

Die Zahl der Finanzinstitute wurde für die statistische

Analyse auf 144 reduziert, da für mehrere Finanzinstitute keine Daten

vorlagen. Anschließend wurde eine Clusteranalyse durchgeführt, um

die Forschungsfrage zu beantworten und Muster, Ähnlichkeiten und

Unterschiede zwischen den ausgewählten Finanzinstituten zu ermitteln. Es

wurden fünf Cluster identifiziert. Aus der Studie geht hervor, dass die

Finanzinstitute maßgeschneiderte und verbesserte Finanzdienstleistungen

für den ländlichen Raum anbieten, welche auf geschlechtsspezifische

Aspekte Wert legen, wie in den Clustern 1, 2 und 3 nachgewiesen wurde.

Darüber hinaus ist die jüngste Gruppe von Instituten in Cluster 4 zu

finden, die die meisten digitalen Lösungen zu bieten hat. In Cluster 5, in

dem sich Finanzinstitute befinden, die hauptsächlich traditionelle

Bankmethoden nutzen, ist das Angebot an Dienstleistungen am geringsten. In

dieser Studie wurde die Forschungsfrage in Bezug auf die Kreditvergabe, die

Förderung der Geschlechtergleichstellung und digitale Lösungen

beantwortet und die Gemeinsamkeiten und Unterschiede zwischen den

Finanzinstituten ermittelt. In dieser Masterarbeit werden mehrere Empfehlungen

ausgesprochen, darunter die Notwendigkeit, Frauen zu fördern und digitale

Lösungen anzubieten, um die Kreditvergabe für Kleinbauern und Akteure

der Wertschöpfungskette zu erleichtern.

Schlüsselwörter: Finanzierung der

landwirtschaftlichen Wertschöpfungskette, Finanzinstitute, Clusteranalyse,

Finanzprodukte, Globaler Süden.

xi

Résumé

Les petits exploitants agricoles et les SME des pays du Sud

sont toujours confrontés à de nombreux obstacles pour

accéder au crédit, malgré les efforts des agences de

développement, les facilitateurs, les gouvernements et même des

institutions financières. Un écart financière agricole

persiste qui limite le potentiel du secteur. La présente thèse de

mémoire examine les moyens par lesquels les institutions

financières facilitent l'obtention de crédits pour les petits

exploitants agricoles et les acteurs de la chaîne de valeur.

L'étude utilise une base de données unique de 347 institutions

financières dans 106 pays d'Afrique, d'Asie, d'Amérique du Sud et

d'Océanie ainsi que des institutions internationales. Elle contient

principalement des coopératives, des banques commerciales, des ONGs, des

institutions de microfinance et des banques agricoles. La base de

données est construite par un processus d'effet boule de neige en

utilisant des sources documentaires, des recherches en ligne et des plateformes

bancaires à code source ouvert. Cette base de données contient

plusieurs détails sur ces institutions, notamment leur type

d'institution, les prêts agricoles disponible, la promotion de

l'égalité des sexes et les solutions digitales offertes par

l'institut.

Le nombre d'institutions financières a

été réduit à 144 pour l'analyse statistique en

raison du manque de données disponibles pour plusieurs institutions

financières. Ensuite, une analyse typologique a été

menée pour répondre à la question de recherche et

déterminer les modèles, les similitudes et les différences

entre les institutions financières sélectionnées. Cinq

regroupements ont été identifiés. Il ressort de

l'étude que les institutions financières fournissent des services

financiers ruraux personnalisés et améliorés, très

demandés et conformes aux questions d'genre, comme le prouvent les

regroupement 1, 2 et 3. En outre, le groupe d'institutions le plus jeune est

l'amas 4, qui a le plus de solutions numériques à offrir. La

grappe 5, qui contient des individus utilisant principalement des

méthodes bancaires traditionnelles, a le niveau le plus bas de services

financiers. Cette étude a répondu à la question de

recherche en termes d'offre de crédit, de promotion du genre et d'offre

de solutions numériques, et a identifié les similitudes et les

différences entre les institutions financières. Plusieurs

recommandations sont formulées dans cette étude, notamment la

nécessité d'encourager les femmes et de fournir des solutions

numériques pour faciliter le processus de prêt pour les petits

agriculteurs et les acteurs de la chaîne de valeur.

Mots-clés : Financement de la chaîne de valeur

agricole, institutions financières, analyse typologique, produits et

service financiers, Sud global.

ÕÎáãáÇ

ÒÒÒÒØ

ÏÒÒÒÒíÏ áÛ

æÒÒÒÒåÌÛæí

æÒÒÒÒäÌáÛ

ÇæÏ ÒÒÒÒ

ÒÒÒÒ æÉØáÛ æ

Ç ÒÒÒÒ áÛ

ÒÒÒÒÔáÛæ

íÒÒÒÒÍáÇáÛ

ÒÒÒÒ

ÇÛÕÒÒÒÒí

Çá

ÏæÒÒÒÒåÌ

ÒÒÒÒØ

ÒÒÒÒáÛ

ÒÒÒÒ åÉ

ÒÒÒÒÔä

ÒÒÒÒÍáÇáÛ

ÇÒÒÒÒíæØÉáÛ

ÒÒÒÒ

ÇæÒÒÒÒ ÍáÛ

æÏ ÇæÒÒÒÒÍÉ

ÒÒÒÒÉáÛ

ÕÌÛæÒÒÒÒÍáÛ

æÒÒÒÒÌáÛ

ÒÒÒÒå

ÏæÒÒÒÒÌæ Û

ØÉÒÒÒÒ Û

ÒÒÒÒíá ØáÛ

ÒÒÒÒ áØáÛ

ÒÒÒÒÉÍæ ì

ÒÒÒÒ æáÛæ

ÒÒÒÒØæ ÍáÛæ

ÒÒÒÒíØäÉáÛ

Çá ÒÒÒÒ æ

í ÉÒÒÒ

Ì ØáÛ

ÒÒÒÍæ Í Ñ

ÏÒÒÒÉ

ÒÒÒÍáÇáÛ

ÒÒÒ áÛ

ÒÒÒä ØÇ

ÒÒÒØ

ÏÒÒÒÍáÛ

ÒÒÒ

ÒÒÒí Ç

ÒÒÒÔ å

ÒÒÒ É

ÒÒÒí Û Õ

áÛ

ÍÒÒÒ Í

æ í

ÛÕÒÒÒØ á

ÇÒÒÒíæØÉáÛ

ÒÒÒ

ÇæÒÒÒ

ÍáÛ

ÒÒÒíá

ØáÛ ÒÒÒ

áØáÛ

ÒÒÒå

ÇåÒÒÒÒ É

ÒÒÒÉáÛ Ó

ÒÒÒ áÛ

ÒÒÒíá

ÍáÛ

ÒÒÒä í

ÏÒÒÒ Ç ÒÒÒ Û

ÏáÛ ÏÇÉÒÒÒ É

ÒÒÒÉä Û ÒÒÒ

ÒÒÒ í ÒÒÒáÛ

ÇÒÒÒ æ ÒÒÒ

æÉØáÛ æ Ç

ÒÒÒ áÛ ÒÒÒ

áØáÛ

ÒÒÒÖ

íÒÒÒ æä

íÇæÍæ ÒÒÒí

æäÌáÛ ÒÒÒ

í ØÍæ

íÒÒÒ æ

ÒÒÒí í Ç

ÒÒÒØ

ÒÒÒáæÏ 106

ÒÒÒØ

ÒÒÒíá

ØáÛ ÒÒÒ

áØ á ÏÒÒÒí

ÒÒÒí ÌÉáÛ

æÒÒÒä áÛæ

ÒÒÒíäæ ÉáÛ

ÒÒÒ ÒÒÒ Í Ç

ÒÒÒÔ ÏÒÒÒ áÛ

ÒÒÒå

æÒÒÒÉÍÉ

ÒÒÒíáæÏáÛ

ÇÒÒÒíæØÉáÛ

ÒÒÒ á Ø

ÒÒÒáÇ

ÏÒÒÒ áÛ

ÒÒÒå ì

ÒÒÒÔäÇ É

ÒÒÒíÍáÇáÛ

æÒÒÒä áÛæ

Ç ÒÒÒ áÛ

ÇÒÒÒíæØÉáÛ

ÒÒÒ áØæ

ÒÒÒíØæ

ÍáÛ ÒÒÒí

ÒÒÒØÙäØáÛæ

ÏÒÒÒÒ ØáÛ

ÒÒÒÒÍæÉØ

æÒÒÒÒä áÛ

ÒÒÒÒ äØæ

ÒÒÒÒä Éä Û

ÒÒÒÒ

æÒÒÒÒÍ áÛæ

ÒÒÒÒí Ï Û Ï

ÒÒÒÒ Ø

ÛÏÇÉÒÒÒÒ

ÒÒÒÒä í á

ÒÒÒå æä

ÒÒÒá ÒÒÒ

ÒÒÒØ ÒÒÒ

áØáÛ ÒÒÒå

ÇæÒÒÒÍ

ÇíÒÒÒ ÉáÛ

ÒÒÒØ ÏÒÒÒíÏ

áÛ ÒÒÒ ÒÒÒå

ÒÒÒä í áÛ

ÏÒÒÒ Ç

æÒÒÒÉÍÉ

ì Í á

æÉØáÛ íØÇ áÛ

Çæ ÍáÛæ í

äÌáÛ í Ûæ ØáÛ

ÌØÛ æ í Û ÕáÛ

Öæ áÛæ áØáÛ

ÏÒÒÒ ÒÒÒ

ÒÒÒ Í Û

ÇÒÒÒí ÍÉ á

ÒÒÒ áØ 144

ÒÒÒáÇ 347

ÒÒÒØ

ÒÒÒíá ØáÛ

ÒÒÒ áØáÛ

ÏÏÒÒÒ ÇíÒÒÒ

É ÒÒÒÉ ÒÒÒØ

ÒÒÒ ÒÒÒ

ÌáÅá ÏæÒÒÒ ä

áÛ ÇÒÒÒí

ÍÉáÛ ìÛ

ÒÒÒÌÇ ÒÒÒÉ

ÒÒÒ ÒÒÒíá

ØáÛ ÒÒÒ

áØáÛ ÒÒÒØ

ÏÒÒÒíÏ á ÒÒÒ

ÇáÛ ÒÒÒä í áÛ

æÒÒÒÉ

ÏÒÒÒíÏÍÉ

ÒÒÒÉ

ÒÒÒÉÇØáÛ

ÒÒÒíá

ØáÛ ÒÒÒ

áØáÛ

íÒÒÒ

ÒÒÒáÇÉÇáÇÛæ

å

ÒÒÒÔÉáÛæ

ÒÒÒØä Û

ÏÒÒÒíÏÍÉæ

æÒÒÒÍ áÛ

ÒÒÒ Í

ÒÒÒÒíí

ÒÒÒÒíá Ø

ØÏÒÒÒÒÇ

ÏÒÒÒÒ É

ÒÒÒÒÉáÛ

ÒÒÒÒíá ØáÛ

ÒÒÒÒ áØáÛ Í

ÒÒÒÒ Û ÏáÛ

ÒÒÒÒØ

ÒÒÒÒÖÉí

ÒÒÒÒ æØÌØ

ÑÒÒÒÒØÇ

2 æ 1

ÒÒÒ

æØÌØáÛ ÒÒÒ

ÒÒÒ ÒÒÒØ

íÒÒÒ äÌáÛ

íÒÒÒ Ûæ ÒÒÒ

ØáÛ ÍÏÒÒÒ Øá

ÒÒÒØ Ï ÒÒÒ Û

ÒÒÒå ÕÕÒÒÒ

Øæ ÒÒÒ ÇØ

ÒÒÒÉáÛ 4

ÒÒÒ

æØÌØáÛ ÒÒÒå

ÒÒÒ áÛ ÒÒÒ

æÉØ ÒÒÒíÍ ä

ÒÒÒØ ÒÒÒ

æØÌØ ÒÒÒ Í

äÒÒÒ ÒÒÒá

ÒÒÒ æáÇ ÒÒÒ

æ 3æ

í ÒÒÒáÛ

ÏÛ ÒÒÒ Û

ÒÒÒ

æÒÒÒÉÍÉ

ÒÒÒÉáÛ

ÒÒÒ Ø ÇáÛ

ÒÒÒ

æØÌØáÛ

åØÏÒÒÒ É

ÒÒÒÉáÛ

ÒÒÒíØÇ

áÛ ÇæÒÒÒ

ÍáÛ ÒÒÒÙ

Ø ÒÒÒÖÉ

ÒÒÒíá ØáÛ

ØÏÒÒÒÇáÛ

ÒÒÒØ

ÇæÉÒÒÒ Ø

ÒÒÒäÏÍ

åíÏÒÒÒá

ÒÒÒíÏí ÉáÛ í

ÒÒÒ ØáÛ íá

ÒÒÒ Û Çæ Û

ÒÒÒ ØáÛ ÒÒÒ

æØÏÇÉÒÒÒ í

ÕÒÒÒíÕ

Éæ

ÒÒÒÍáÇáÛ

ÇÒÒÒíæØÉáÛ

íæÒÒÒÉ

æÒÒÒíÍ

ÒÒÒØ

æÒÒÒÍ áÛ

á ÒÒÒ Ø

ÒÒÒ Û ÏáÛ

ÒÒÒå

ÒÒÒáæ äÉ

ÒÒÒíÍáÇáÛ

ÒÒÒíá

ØáÛ

íÒÒÒÒ

áÇÉÒÒÒÒÇáÇ

Ûæ ÒÒÒÒÔÉáÛ

ÒÒÒÒÌæÍ

æÒÒÒÒä

ÏÏÒÒÒÒÍ á

ÒÒÒÒ æ

ÒÒÒÒíØÇ áÛ

ÇæÒÒÒÒ ÍáÛæ

íÒÒÒÒ äÌáÛ

íÒÒÒÒ Ûæ

ÒÒÒÒ ØáÛ

ÒÒÒ Û ÏáÛ

ÒÒÒå ÒÒÒ

íÒÒÒ æÉáÛ

ÒÒÒØ ÏÒÒÒíÏ

áÛ íÏÒÒÒ É

ÒÒÒÉ

ÒÒÒÍáÇáÛ

ÇÒÒÒíæØÉáÛ

ÒÒÒ ÒÒÒ áÛ

ÒÒÒíá ØáÛ

ÒÒÒ áØáÛ

ÒÒÒ á ÖÛ

ÒÒÒÇ Û

ÒÒÒí Ø

ÇíåÒÒÒ

Éá

ÒÒÒíØÇ

ÇæÒÒÒ Í

íÏÒÒÒ Éæ

ì ÒÒÒ äáÛ

ííÌÒÒÒÔÉ

ÒÒÒáÇ

ÒÒÒÌ ÍáÛ

ÒÒÒá

ÒÒÒ

ÒÒÒØ

æäÌáÛ ÇæÏ

Éä Û íØå ØáÛ

Ç æ íÍáÇáÛ

ÇæÏ

ÒÒÒÒíá ØáÛ

ÇæÒÒÒÒ ÍáÛ

ÏæÒÒÒÒ ä áÛ

ÇÒÒÒÒí

ÍÉáÛ

ÒÒÒÒíá ØáÛ

ÒÒÒÒ áØáÛ

ÒÒÒÒÍáÇáÛ

ÇÒÒÒÒíæØÉáÛ

: Í ÒÒÒÒÉØáÛ

ÒÒÒÒØ áÛ

xii

æäÌáÛ

1

1. Introduction

1.1. Problem statement

Agriculture in developing countries is undergoing major

changes, including globalization and the transition from traditional low

production agriculture to modern high production agriculture. The result of

this process of profound changes has important consequences on poverty, risk

management and agricultural smallholders' income (Abid, Jie, Aslam, Batool,

& Lili, 2020). Smallholders face severe problems resulting from the

specificity of the production cycle. They have also to deal with climatic

factors such as extreme weather shocks and biological factors like insect

pests, crop, and livestock diseases (Fries & Akin, 2004). These production

risks are linked with price and market risks. Therefore, the variability of

production provokes high food price instability (Antonaci, Demeke, &

Vezzani, 2014). Due to this high risk, financial institutions are less

interested in financing the agricultural sector because of low profit and low

collateral (Herliana, Sutardi, Aina, Himmatul, & Lawiyah, 2018). Moreover,

Financial Institutions (FIs) consider micro-entrepreneurs as

"non-bankable», or not creditworthy because they have no previous credit

history or guarantee to offer (Yunus M. , 2007). On the other side, farmers

often face multiple challenges to access the finance they require, the outcome

is thus a financing gap that limits the potential of agriculture (UNCTAD,

2004). This financing gap which exists in the agricultural sector is estimated

at about $170 billion per year (ISF Advisors and Mastercard Foundation, 2019).

Development agencies, research institutes and donors have centered their

efforts on developing new approaches that allow different stakeholders, such as

agribusiness, and financial institutions to address this gap. The aim is to

provide innovative financial services to producers, processors and traders as

well as develop an economic and financial environment (IFAD and CPI, 2020).

Among these approaches, we can find Agricultural Value Chain

Finance (AVCF) which refers to leveraging the a value chain's connections and

social capital to improve financial flows and reduce the risks in the chain

(Miller & Jones, 2010). Whereas many of the value chain finance

transactions, instruments, and processes are not new (Robert, Chalmers, &

Grover, 2012),what is new is how AVCF is used by FIs and rural producers. What

is also innovative is the variation of the application and the different

organizations that offer finance in different innovative ways, as well as the

diversification, the intensification, and combination of mechanisms (Miller

& Jones, 2010). It also means linking financial institutions to the value

chain, providing financial services to support the flow of products, and

building on the relationships established at the chain level. This type of

financing offers alternatives to traditional requirements (KIT and IIRR, 2010).

This allows all value chain participants to benefit from it without collateral

requirements (Cuevas & Pagura, 2016). AVCF differs from other types

2

of financing in that it expands financing opportunities for

agriculture and improves repayment efficiency among chain participants. It is

not only that the nature of the funding is different, but also the motivations.

Nyoro (2007) mentions that `value chain actors are driven more by the desire to

expand markets than by the profitability of the finance' (Nyoro, 2007). The

solutions offered by AVCF can help to build a value chain, mitigate barriers,

or improve value chain operations, thereby increasing the competitiveness of

the chain (KIT and IIRR, 2010). The challenges that AVCF can face are legal

systems that enforce contracts and provide some type of ownership, lack of bank

penetration and institutions offering loans for investment in rural areas, high

transactions cost, lack of knowledge and developed infrastructure (Zander R. ,

2016).

1.2. Objectives

Recent work has focused on evaluating the access to finance at

the farmers' level (Gamage, 2013), however, there is limited evidence on the

role of Financing Institutions (Meyer R. L., 2002), in particular, in new

approaches such as Agricultural Value Chain Finance. This master's thesis aims

to build a database of financial institutions that fund agriculture in the

Global South. A number of different financial institutions are included in the

database, including a range of institutional types and banking experience, as

well as the services offered by each institution. Following that, a descriptive

analysis of the data from these institutions will describe the basic features

of the data. This analysis will provide simple summaries of data and draw

conclusions from it. A later study can use this database to conduct the online

questionnaire with these FIs. This will enable research staff to determine the

methods that financial institutions use about credit screening, scoring, and

agricultural value chain financing. A part of this thesis involves analyzing

the existing questionnaire and preparing the basis for the design of the

questionnaires [Annex C]. From this database, a cluster analysis using R

will be able to draw conclusions about lending to farmers and credit for value

chain participants. The aim of this study is to provide robust evidence

regarding the similarities and differences between financial institutions when

it comes to offering rural services to their clients.

1.3. Research questions and hypothesis

The present study will focus on the role of financial

institutions in implementing value chain finance in the Global South. This

study will address the following questions:

1) What are the key underlying characteristics of credit

provision of different types of financial institutions in the Global South?

2) What is the extent to which financial institutions promote

gender issues and offer digital solutions?

3

3) What kind similarities and differences can be observed

between financial institutions? As a result, the present work highlights the

subsequent main hypotheses H1, H2 and H3:

H1: Various trends can be seen on the basis of the variables

concerning the provision of credit by different types of financial institutions

in the Global South.

H2: Only a few financial institutions deal with gender issues

and offer digital solutions

H3: Financial institutions show several similarities and

differences in credit provisions, gender programs, and digital solutions.

1.4. Expected results from the research

The expected outcomes of this study are:

i. A database of financial institutions which fund agriculture

in the Global South.

ii. Data-driven evaluation of financial institutions' services

in the Global South

iii. An agenda for agricultural finance policy

recommendations

1.5. Organization of the thesis

Throughout this study, six sections are discussed. The

following part is a literature review which covers theoretical perspectives

about agriculture finance, AVCF definitions and challenges, and a review of

available papers, as well as agricultural credit determinants. In the third

section, we describe the study, the way the database was built, and the

statistical methods used. The fourth section focuses on the design of the

survey. In part five, we examine the results of our descriptive and cluster

analyses. Lastly, the fifth part summarizes the findings, discusses them, and

makes policy recommendations. The Annex «C» contains the

survey.

4

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Background

2.1. Agriculture finance

2.1.1. Agricultural credit

Several interventions are needed in the form of financial

institutions and instruments at the value chains (VCs) level to improve

financing in the agricultural sector. This interest has been renewed following

the economic crisis and the increase in food prices in 2008 and 2011 (Arias,

2019). In most developing countries, the level of financing and public

expenditure on agriculture remains very low. This reflects the low percentage

of the share of agricultural credit of total credit (Piñeiro, 2019).

Moreover, according to the agriculture orientation index (AOI) for credit,

agriculture financing is still also low and is just 0.4 in developing

countries, while in developed countries it is 1.95 (Arias, 2019).

According to Adams (1994), rural producers need access to

financing at the right time and this needs to be stable and reliable for more

than a few cropping seasons. This is designed to improve the production and

marketing process as well as to have access to input, new technologies and

limited resources (Zander R. , 1994). While rural credit is a powerful

instrument for poverty alleviation (Ololade & Olagunju, 2013), supporting

the agricultural sector is always complicated for FIs because access to

information is very expensive and difficult. Moreover, the soft skills in

lending to small-scale farmers are not well developed (Zander R. , 2016).

Many studies on the agricultural credit in developing

economies have shown that agricultural lending is necessary to improve

productivity in the agricultural sector (Sriram, 2007; Das, Senapati, &

John, 2009). Other studies have found that without external financing,

small-scale farmers cannot even continue their business, and this is proved in

the history and debts of people working in agriculture (Gowhar, Ganie, &

Padder, 2013). Agricultural credit is therefore a necessary element in meeting

the need for investment and bridging thegap between the farmer's income and the

expenditure in the field (Khan, Shafi, & Shah, 2011). Additionally,

Agriculture credit plays a key role in the modernization of agriculture by

removing financial constraints and accelerating the adoption of new

technologies (World Bank, 1975).

In this context, Singh et al. (2001) announced that most farm

households face a lack of funds on their side. To meet their credit

requirements, both formal and non-formal financing is available in a developing

economy. Pradhan (2013) suggests that farmers' need for credit increased

spontaneously after the Green Revolution. This was the period when

institutional sources of credit were considered major players. This was the

time when subsistence crops were replaced by cash crops. These credit sources

were classified in the following figure into

three groups by Yadav and Sharma (2015) following their

intensive literature review on agricultural credit.

Agriculture credit

Non-

institutional

sources

Semi-

institutional

Sources

Institutional Sources

5

Figure 1: Sources of agriculture credit

Source: Yadav & Sharma (2015)

Figure 1 shows the main sources of credit that are available

to rural producers. Credit from institutional sources includes credit from the

creation of institutional framework with banks and institutions including

specific organizations established for agricultural development, commercial

banks, cooperative banks, and regional rural institutions. Non-institutional

sources cover credit from the unorganized sector such as friends, relatives,

landlords, entrepreneurs who are not part of the institutional set-up (Ijioma

& Osondu, 2015). Halfway between the institutional and non-institutional

agencies is the semi-formal configuration of microfinance and the provision of

a range of financial and non-financial services to members based on joint

responsibility (Yadav & Sharma, 2015).

Regarding the components of agricultural credits, Yadav &

Sharma (2015) highlight direct credit, which includes short-term loans,

medium-term loans, and long-term loans for agriculture and connected activities

with direct responsibility for repayment. According to Gowhar et al. (2013),

short and medium-term loans are provided by cooperatives, commercial banks, and

regional rural banks for agriculture and allied activities. Whereas, long-term

loans for agriculture are provided by rural development banks and primary

cooperatives. Short-term agriculture credit enables farmers to buy inputs such

as fertilizers, seeds, power, irrigation and the cost of the hired labor

(Osuntogun, 1980; Adebayo & G, 2008). Short-term credit is practically for

6 months. However, long-term credit is oriented toward large investments such

as irrigation pumps, tractors, and agricultural machinery (Anwarul &

Prerna, 2015). While indirect credit allows the farmer to benefit from

subsidized inputs and warehouse facilities. In this case, farmers are under

indirect repayment responsibility through fertilizers dealers and

6

input suppliers. Figure 2 summarizes the components covered

under the scope of institutional credit.

Direct Credit

Indirect Credit

Subsidized Inputs

Warehouse facility

Setting up

agribusiness centres

t

Credi

Agricul

ture

Short term loans

Medium term loans

long term loans

Figure 2: Components of direct and indirect agriculture

credit Source: Yadav & Sharma (2015)

2.1.2. Financial institutions (FIs) in the Agriculture

Sector

Financial institutions (FIs) are organizations that engage in

the business of facilitating financial and monetary transactions. There are

different types of financial institutions in a developed economy. Financial

institutions cover also commercial banks, insurance companies, and brokerages

firms. Furthermore, financial institutions can differ by size, scope, and

geography. They offer a wide range of products and services such as

transactions, deposits, loans, investment, and currency exchange.

In the agricultural sector, the main source of loans for

smallholders' farmers and agribusinesses are other

agribusinesses in the VC. However, farmers and agribusinesses can benefit from

credit offered by FI. These providers of rural and agricultural finance can be

broadly Banks (commercial, agricultural banks, state development banks),

non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs, commercial MFIs, other non-bank

lenders, and leasing companies), Not-for-profit MFIs, which tend to work with

poorer clients, and Credit unions and agricultural cooperatives.

KIT and IIRR (2010) have shown that IFs have the capacity to

develop new markets for all actors in the chain and make them bank customers.

In the Global South, agriculture is the backbone of the economy, then the

capacity to benefit the sector can significantly increase the actions of

FIs.

2.1.3. Microfinance

Generally, the term MFI is given to non-profit organizations

that depend on donations and grants to enable them to fulfill their primary

social role of poverty alleviation (D'Espallier, 2012). Thus, in its limited

concept, microfinance is the provision of micro-credit for small entrepreneurs

who lack access to the formal financial system. Over time, Microfinance has

developed from providing micro-loans for low-income people to collecting

savings, micro-insurance, micro leasing, assisting with money transfer in

relatively small transactions for disadvantaged people, and finally marketing

and distributing client's products (Thai-Ha, 2020; Ferdinand & Asmah,

2012). MFIs play a key role to boost the social capital and the inclusion of

disadvantaged populations and serve hundreds of millions of low-income

borrowers (Morduch, 1999) because it allows access to credit to non-bankable

people with all the advantages from banking services (Yunus & Jolis, 1999).

The aim is to reduce poverty and develop economies, especially in Asia and

Africa. Moreover, microfinance has enabled smallholders to improve the living

standards of people, increase income and generate employment (Thai-Ha, 2020). A

web-based report on microfinance shows a practical framework for understanding

how MFIs function after a typical microfinance intervention using the

illustration in Figure1 3. The main objective of microfinance is

economic empowerment through the use of micro-credit as an entry point for

overall empowerment.

7

Donors and Banks

Micro Enterprise

Production Needs

Farm related

Micro Enterprise

Production Needs

Non-Farm related

Individual

Promotional work,

Formation

Implementing Org.

Credit Delivery,

Recovery,

Monitoring

Income generation

Economic

Empowerment

Individual

Figure 3: Development Process through Micro-finance

1 Source: (Ferdinand & Asmah, 2012, p. 76), Accessed: 18 July

2021

See

https://journals.ug.edu.gh/index.php/gssj/article/download/1174/774#page=78

8

Source: Ferdinand & Asmah (2012)

Concerning the differences between these stakeholders,

microfinance is a financial service that caters to the needs of the poor and

micro enterprises, and it is typically a collateral-free short-term loan. In

contrast, commercial banks generally do business with corporate clients, SMEs

and individuals with higher incomes, and offer financing mainly based on

collateral and repayment capacity. Alternatives include central banks serving

the banking system. They facilitate cross-border transfers of money between

banks and government institutions, both domestically and abroad. This flow is

required while MFIs are complementary, not substitutes for, banks, donors, and

state banks (Miguel & Silvana, 2007). In the figure above, we can see how

effective collaboration between social welfare programs, MFIs, state Banks, and

commercial banks may lead to greater poverty alleviation.

According to Ferdinand & Asmah (2012), this reduced

process depends on microfinance's use to create a sustainable environment and

more opportunities. Success in implementing microfinance is mainly linked to

the ability of MFIs to meet the objectives of Donors and Banks in facilitating

credit approval and the increase in the percentage of borrowers' repayments.

MFIs are always adopting different innovations to expand the

delivery of microfinance in rural areas, Meyer (2007) announced several new

products, technologies, and institutional connections intending to target rural

areas and make financial services available for rural households. Some

moneylenders use standing crops as collateral for loans. Others take assets as

collateral for short-term farm and non-farm loans (World Bank, 2007).

Gonzalez & Rosenberg (2006) compiled a database that

includes 2600 MFIs with 94 million borrowers. This database encompasses several

micro-credit providers that are granted by a variety of FIs. The following

table2 1 shows the approximate share of each type of FIs in the

approval of micro-loans.

Table 1: Distribution of MFIs by institutional type

Institutional type Percentage %

|

State owned banks

|

30%

|

|

State owned Institutions

|

30%

|

|

NGOs

|

25%

|

|

Private banks and finance Companies

|

15%

|

2 Source: Gonzalez & Rosenberg (2006, p.2) Accessed 17 July

2021

See

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228276752

The State of Microfinance -

Outreach Profitability and Poverty Findings from a Database of

2300 Microfinance Institutions

9

Source: Gonzalez & Rosenberg (2006)

In the agricultural sector, various authors have concluded

that microfinance boosts short-term agriculture investment, earnings, and

consumption (Kaboski & Townsend, 2012; Mosley & Hulme, 1998).

Unfortunately, while microfinance shows positive impact on Agriculture and

Transformation, it has not solved the challenges r thatsmall-scale farmers

face. Moreover, it has not shown a significant impact in terms of employment,

increased income flows, and physical asset accumulation (Ferdinand & Asmah,

2012; Buckley, 1997; Coleman, 1999). In this context, some Scholars have

enumerated several faults such as the high-interest rate, aggressive collection

method, and driving people into debt (Thai-Ha, 2020). Besides, Diagne und

Zeller (2001) have found following their study in Malawi that microfinance does

not show any significant effect on household's revenue (Diagne & Zeller,

2001).

Hence, microfinance has its limitations and faces several

challenges in lending to small-scale farmers. For this reason, continuous

innovations are needed to enable MFIs to be more efficient in improving

farmers' income, poverty alleviation, and economic empowerment while making

service providers more sustainable over time.

The following section focuses on the Agriculture Value Chain

Finance (AVCF) approach, which can complement and go beyond microfinance. The

important difference here is that AVCF is linked to all actors and

relationships in the chain in addition to transactions. Therefore, this concept

can join several actors in microfinance. In addition, microfinance can be part

of AVCF but must be with other financial services to address the different

needs of the chain (KIT and IIRR, 2010).

2.2. AVCF definition

There is still no unified definition of AVCF. Different

authors show an understanding with various characteristics on this subject.

However, one of the most widely accepted definitions is the one formulated by

Miller and Jones (2010), who define value chain finance as:» the flows of

funds to and among the various links within a value chain" and distinguish

between internal and external value chain finance. Likewise, authors from FAO

and AFRACA (2020) defined AVCF as two internal flows of financing between chain

actors directly within the VC and for financial service providers who use AVCF

to lend money or to invest in one or more of the chain actors. However, the

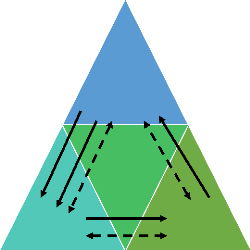

authors of KIT and IIRR (2010) have defined the VCF triangle, in which FI

engages with the actors of the chain. This triangle is among FI, the seller and

the buyer. The figure below illustrates the VCF.

Seller

financial institution

VCF

triangle

Buyer

10

Figure 4: Overview of value chain finance Triangle

Source: KIT and IIRR (2010)

This figure shows the payment, loan, and information and

services flows between the financial institutions and the seller. Additionally,

the payment and information flow between buyer and FI. Eventually, the flows of

information and services and product between the buyer and the seller.

Complementarily, a study by Carroll et al. (2012) provides a

pragmatic definition of AVCF:

...in the case of agriculture, the value chain may include

(but is not limited to) input provision, production, processing, transport,

storage marketing, and export.

Additionally, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) (2012) makes the

definition of AVCF simpler:

...organized linkages between groups of producers, traders,

processors, and service providers (including nongovernment organizations) that

join together to improve productivity and the value-added from their

activities.

Similarly, Zander (2016) presented the following

definition»:

Value chain finance (VCF) denotes all financing arrangements

within a specific value chain or from outside the chain. As the concept of

value chains and their financing is broad and multifaceted, the terms `value

chain' and `VCF' necessarily refer to a broad range of different instruments

and mechanisms.

Finally, a recent study by Villalba, Venus, & Sauer (2021)

explains Agricultural Value Chain Finance (AVCF) as:

A variety of products and approaches that allow stakeholders

from a value chain to leverage social capital and satisfy the funding needs of

the weakest actors. Cooperating within a value chain reduces risk, which can

facilitate the

11

acquisition of financing from financial institutions, and other

lenders at a lower

cost.

While no common definition has been proposed in the

literature, ADB (2012) and Carroll et al. (2012) have the constituting element

«provision», «processing», and «productivity» in

common. They show that the chain starts from the raw material stage to the

final consumer. However, other researchers explain this term as a variety of

different products, mechanisms, and instruments used by different actors in the

chain to initiate financing arrangements (Villalba, Venus, & Sauer, 2021;

Zander R. , 2016).

There is agreement between the literatures when it comes to

the flows of funds. (Miller & Jones, 2010; KIT and IIRR, 2010; AFRACA and

FAO, 2020). In addition, there are definitions of AVCF for which the authors

partially agree such as internal and external value chain (Miller & Jones,

2010; AFRACA and FAO, 2020).

The authors agreed that Internal Value chain finance takes

place within the value chain such as when an input supplier provides credit to

a farmer, or when a lead firm advances funds to a market intermediary. External

value chain finance is that which is made possible by value chain relationships

and mechanisms: for example, a bank issues a loan to farmers based on a

contract with a trusted buyer or a warehouse receipt from a recognized storage

facility.

Other authors defined AVCF as a triangle, in which, an

agreement between the actors (FI, seller and buyer) is made around the product,

the need for financing, the sharing of information, the method of

communication, and finally the way of risk management (AFRACA and FAO, 2020).

This agreement according to KIT and IIRR (2010) allows the development of the

value chain in three different ways:

a) Ensuring liquidity for the actors of the chain

b) Creation of new chains

c) Investments in existing chains

This highlights how general financing of agriculture works,

(new investments, reinvestments, and financing of current assets) and is a

useful typology for value chain development.

2.3. AVCF Challenges

About the challenges of AVCF, the authors have listed several

constraints that buyers and suppliers face in lending to farmers as shown in

the following Table 2.

12

Table 2: The challenges of the agriculture finance according

to the literature review

|

Challenges

|

Author(s)

|

|

Pearce

(2003)

|

Langen bucher

(2005)

|

Honohan and

Beck

(2007)

|

Meyer

(2011)

|

IFC

(2012)

|

AfDB

(2013)

|

Klonner and Rai

(2015)

|

Herliana

(2018)

|

ISF

(2019)

|

|

Financial

exclusion of

farmers

|

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

information asymmetries

|

X

|

X

|

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

Transaction cost

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

High fees

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

insufficient amounts of credit

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

X

|

|

Low

infrastructure, distant location

|

|

X

|

|

|

X

|

|

|

|

|

|

Low Education of farmers

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

|

|

Fluctuating Production

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

|

|

Lack collateral

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

|

|

Inefficient Market

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

|

|

|

|

The challenges cited in most literature studies are the

following:

Financial exclusion of farmers: according to

Langenbucher (2005) the causes of financial exclusion for the small farmer from

the supply side are the lack of robust business models, and limited access to

equity capital. Likewise, the key features that influence value chain finance

(VCF) are the high incidence of informality (lack of documentation and

contract), the intermediation deficiency (high-interest rate and minimum

deposit), and the dominance of the banking sector (lack of information about

credit worthiness of potential clients, weaknesses of the legal system, and

high degree of corruption and inefficient bureaucracies. (Langenbucher, 2005;

Honohan & Beck, 2007; Meyer R. , 2011). Meanwhile, formal institutions are

less interested in financing the agricultural sector due to several constraints

and subsequently obtaining formal credit is a complex procedure (Herliana,

Acip, Qorri, Qonita, & Nur, 2018).

Information asymmetries: in accordance with

Pearce (2003) and Langenbucher (2005), which makes the agricultural environment

very complicated, are a lack of information about

13

14

smallholders' farmers and risk of agricultural activities. In

addition, this sector is complicated due to the unique problem of the

agricultural sector, the inadequate policy, regulatory environments, and

asymmetric information (IFC and World Bank, 2012; Herliana, Acip, Qorri,

Qonita, & Nur, 2018). In addition, several studies cited that FIs are not

aware about farmer's credit worthiness, and therefore, smallholders' farmers

are left when FIs try to mitigate risk (Klonner & Rai, 2005; IFC and World

Bank, 2012; Pearce, 2003). Thus, banks were not investing adequately to

understand the demands and nuances of value chains (VCs). This lack of

information leads to the design of financial products that are not suitable for

rural activities (AfDB, 2013).

Transaction cost: can be viewed from a

financial point of view as a difference between the price a broker pays for a

security and the price the buyer pays (Cheung, 1987). Most authors agree that

transaction costs are one of the most important constraints that FIs have to

deal with (Langenbucher, 2005; IFC and World Bank, 2012; AfDB, 2013). According

to Pearce (2003), buyer and suppliers face difficulties in lending to farmers.

Among these difficulties, he mentioned transactions cost as a major problem.

Following the bibliographical study concerning the

constraints, the authors show a partial compromise about the following

challenges:

High fees: as defined in the report of the

AfDB (2013), small farmers who already have access to loans find the terms very

rigid and the fees too high, which causes an increase in production costs. As a

result, they borrow money from family and friends, or money lenders who charge

high interest and limit their potential to expand (IFC and World Bank, 2012;

Herliana, Acip, Qorri, Qonita, & Nur, 2018).

Insufficient amounts: according to ISF

Advisors (2019), small farmers in South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and Latin

America need about USD 240 billion for agricultural and nonagricultural

finance. Service providers are not able to meet this demand and the latest data

collection indicated that financial service providers provided only USD 70

billion distributed as follows: USD 30 billion by value chain actors, USD 21

billion by formal financial institutions, and USD 17 billion by informal and

community-based financial institutions. This shows that 70% of the global

demand of small farmers remains unsatisfied, the equivalent of USD 170 billion

and the contribution of FIs remains minimal (ISF Advisors and Mastercard

Foundation, 2019). Additionally, most loans are short-term which cannot improve

the output and income (AfDB, 2013). Moreover, lenders confront irregular

payments and slow rotation of capital (IFC and World Bank, 2012).

Low infrastructure and distant location:

While Langenbucher (2005) in this context has listed the lack of

appropriate risk mitigation and infrastructure, and no branches or limited

network in rural areas, the authors of IFC (2012) enumerated

the low population densities, low infrastructure, distant locations, and the

inefficient market, which can only worsen the situation and decrease

profitability.

Finally, other challenges were listed separately and show less

compromise between the others:

Low education of farmers one of the barriers

to agricultural finance is the low education level of small farmers (Herliana,

Acip, Qorri, Qonita, & Nur, 2018). This low literacy level of cultivators

is the main cause of the limited access to information which translates to low

efficiency in resource management and then low productivity crops. This low

productivity is due to the lack of knowledge about the right proportion of

Inputs (seeds, chemical fertilizers, and pesticides). Besides, in a present

changing environment, farmers are unable to compete which traps them in a

vicious circle of poverty.

Fluctuating Production Most banks avoid

financing agriculture on the ground of fluctuating production and uncontrolled

price risk (Herliana, Sutardi, Aina, Himmatul, & Lawiyah, 2018). The main

causes of the fluctuating production are climatic factors such as: water,

light, rainfall, and temperature which lead to unpredictable food production

(Gilbert, 2010). In addition, ecological land change and cultivated land

intensity will make the production more complicated (Xie, He, & Xie, 2017;

Xie, He, Zou, & Wu, 2016).

Lack of collateral Herliana (2018) showed

that FIs avoid financing small farmers following the low profits and lack of

collateral. Besides, rural producers do not generally have assets that IFs are

willing to accept as collateral. In addition, pledges of agricultural assets

have often been insufficient to ensure credit recovery, thus threatening the

sustainability of development Financial Institutions (FAO and ALIDE, 1996).

Inefficient Market According to IFC authors

(2012), unstable market prices aggravate the financial situation of small

farmers. Food demand is constantly rising due to growing population. however,

food supply is dropping due to increasing production cost. This imbalance in

food demand and supply is the primary cause of the price volatility (Lu, 1999).

Besides, continuous changes in input and output prices reduce the income of

small farmers (Ijioma & Osondu, 2015).

2.4. Competitiveness of agricultural finance

According to Abid et al. (2020), to achieve the objective of

reducing transaction costs (TC) and risk management, several factors should be

considered by organizing chain actors in VCF. Among these factors3,

we can mention; Agility, Innovativeness, Information sharing, Trust,

3 Source: Abid et al. (2020)

15

Information & Communication, and Contractual Governance

(Abid, Jie, Aslam, Batool, & Lili, 2020).

Information Sharing

Agility

Trust

Competitiveness

Information & Communication

Innovativeness

Contractual Governance

Figure 5: Considered factors to reduce TC and risk management

in agricultural finance

i. Agility: which is the ability to respond

to changing customer needs and satisfy

the unique needs of each customer

with flexibility and adapt to unforeseen circumstances (Abid, Jie, Aslam,

Batool, & Lili, 2020). Then, agility in the value chain allows the FIs to

respond quickly to the needs of customers and then ensure competitiveness in

the chain. This accelerates the financial flow in the VC and reduces the

intervention of informal money lenders (Ellis, 1992). In the same scope of

work, Meyer (2007) emphasized the important role of the intervention of FIs in

identifying the unmet demand and to find where the lending cost and risks are

lower. He mentioned that this follows up requires more analysis to design

appropriate product, improve lending capacity, and make diversified loans

portfolio. Therefore, Agility in the VCF improve competitiveness with respect

to financial product and innovation (Swafford, Ghosh, & Murthy, 2006).

ii. Innovativeness: is a system in which VC

actors provide new products and

services to increase customer satisfaction

(Simon & Yaya, 2012). The authors of IFC (2011) and Hult (2004) found that

FIs need to develop new credit skills and policies, credit scoring and rating

tools, as well as portfolio monitoring practices to provide high value

customers. The way of lending credit to farmers is parametric, while it is

based only on a few parameters due to the lack of collateral. This should be

improved, developed, and replicated. Generally, FIs

16

with a high degree of innovation can adapt to every change in

the environment and ensure more competitiveness within the VC. Moreover,

according to Kaufmann (2000), FIs can improve their ability by strengthening

the process of product innovation by organizing producers and buyer's

relationship. Equally, According to Röttger (2015), FIs should understand

the risks and opportunities of the sector and link loan with insurance

products.

iii. Information sharing: according to Brown

(2010) and Pagano (1993),

Information sharing describes how the actors in

the chain react to each other over time. Information sharing is very important

as it improves market competitiveness, credit allocation efficiency, reduces

asymmetric information, and increases lending volume. Furthermore, the sharing

of information helps FIs to address asymmetric information using the network,

incorporate the collaboration with VC actors to design innovative product

(Miller C. , 2012; Röttger, 2015), in this regard, the authors of KIT and

IIRR (2010) and Kim (2017) highlighted that information sharing return the

relationships in the chain smooth and simplified and build better partnership.

Moreover, the cost of credit screening, monitoring and enforcement are reduced

due to chain actors, which take part in this procedure and do this work

themselves and make agile the VCF (KIT and IIRR, 2010; Kim & Chai,

2017).

iv. Trust: Trust is about how reliable and

credible the partners in the value chain

consider themselves to be (Abid,

Jie, Aslam, Batool, & Lili, 2020). Trust is therefore considered as an

important element to overcome unexpected situations and to act in situations

perceived as risky (Song, 2018). According to Jones et al. (2015) trust between

stakeholders is an essential requirement for successful management of financial

flows in the value chain. In this context, Miller, and Jones (2010) mention

that trust between producers and buyers is one of the key factors to mitigate

risks. Thus, the adoption of an agile approach VCF is based on a better level

of trust (Svensson, 2001).

v. Information & Communication:

according to Ali et al. (2011) and Imtiaz et al.

(2015), Information and

communication enhance the creditworthiness of smallholder's farmers, reinforce

partnerships between value chain actors, minimize the cost of stakeholder

interaction and the risk related to the VCF. For more effectiveness and risk

reduction through information and communication, the authors of IFC (2012) have

mentioned the development of insurance products, such as crop and weather

insurance products, credit life product, and emerging health and FIs should

rely on cash flow, saving or group guarantee, then within their value chain and

take advantage of all information to develop

17

adequate product that combine financial and non-financial

services. Besides, FIs should improve their capacities to assess farmer credit,

develop insurance and risk-sharing, and identify opportunities to increase

their level of comfort and reach more farmers (IFC and World Bank, 2012).

Likewise, Röttger (2015) highlighted the importance of relying on the

recommendations of group leaders and extension agents in the aim of linking

loan with insurance products, increasing loan amounts, and declining interest

rate. Zhao et al. (2019) have found that the use of information facilitates

innovation in financial services, lower costs, monitor risks, and allow for

agile financial flows.

vi. Contractual Governance: is the degree to

which a contractual partnership is

legislated by a formal contract

specifying formal rules, responsibilities, and duties (Zhou & Poppo, 2010;

Cao & Lumineau, 2015). Moreover, it supports innovation-based coordination

and strict collaboration between actors. This cooperation between value chain

partners, according to Anna Grandori (2019), regulates transactions and the

pooling of resources, and thus, procedures for innovation. According to the

authors of the AFRACA (2020), AVCF offers several advantages for chain actors.

Starting with producers, AVCF makes it easier for them to get credit because of

the lack of collateral. Then, for agribusinesses, AVCF strengths the

buying-selling relationship and allows market expansion. Finally, for FIs and

investors, AVCF reduces transaction costs, improve repayments, and mitigates

risk due to more suitable financial products. Due to the absence of FIs in most

rural areas because of cost and risk of agriculture lending are too high, the

authors found that FIs can take advantage of the collaboration in the VC and

work with companies rather than directly with farmers to deal with these

risks... Eventually, the public sector has a crucial role for a suitable policy

and banking regulations that allow the application of new approaches, and

infrastructure.

2.5. Determinants of agricultural credit

Several studies have been done in the past on the

identification of the determinants of agricultural credit and the factors that

significantly influence the decision (Akpan, et al., 2013; Salami &

Arawomo, 2013; Yuan, Hu, & Gao, 2011), many variables (factors) have been

identified in the literature leading researchers to analyze their impact on the

decision of credit accreditation (Abid, Jie, Aslam, Batool, & Lili,

2020).

To start with Meyer (2007), FIs need to ask farmers before

lending, such as others engaged in economic activities for the households, cash

inflows and outflows, source of income for

repayment, and structure of the given loan. This can help FIs

to determine the amount to be lent to the specific VC, and the method to

mitigate risks. Thus, this evaluation allows determining the creditworthiness

of farmers, the types, terms, and conditions of financial products needed to

meet these demands. Other studies have also identified specific factors for the

allocation of credit such as education, marital status of the household,

contact with extension agents, years of experience in farming, land size,

gender, etc. (Aliero & Ibrahim, 2011; Dzadze, Osei, Aidoo, & Nurah,

2012; Akpan, et al., 2013). Among other socio-economic factors, being a member

of a cooperative plays a key role in access to credit (Ijioma & Osondu,

2015). A recent paper in Pakistan has shown also that health status remains one

of the determinants for credit accreditation (Saqib, Kuwornu, K.M., Panezia,

& Ubaid, 2018).

According to Gammage (2013), access to bank finance is

determined by a number of factors such as ownership type, age of the firm,

sector, and location of the business, assess tangibility, firm performance,

availability of audited financial statements, gender of the owner-manager and

perception of the owner-manager of access to bank finance, and characteristics

of the borrower at the time of evaluating loan applications. According to Abid

(2020), the most common factors are literacy, size of land, marital status, and

distance to a lending institution, age of the borrower, caste, religion, and

value of assets held by the household. Another study in Nigeria found a

significant relationship between gender, marital status, the lack of a

guarantor and access to credit (Ololade & Olagunju, 2013). In addition to

gender, agricultural experience, education level, farm size, and income,

household size and availability of collateral have a meaningful effect on loan

accreditation for farmers (Abbas, Yuansheng, Feng, & Liu, 2017).

From the review, these factors were classified into three

groups based on common characteristics, characteristic linked to the farmer

(Gamage, 2013; Ololade & Olagunju, 2013; Ijioma & Osondu, 2015), others

linked to the farm (Aliero & Ibrahim, 2011; Gamage, 2013), and finally

those linked to the economic activity (Meyer R. L., 2007; Gamage, 2013), as

shown in the Table4 3.

18

4 Source: The Author

Summary of different research on the determinants of access to

credit

Table 3: Determinants of credit Access

19

|

Farmer

|

Farm

|

Economic Activity

|

|

·

|

Education

|

·

|

Land Size

|

·

|

Cash inflows and

|

|

·

|

Marital status

|

·

|

Ownership type

|

|

outflows

|

|

·

|

Household size

|

·

|

Age of the firm

|

·

|

Source of income for

|

|

·

|

Years of experience

|

·

|

Sector

|

|

repayment

|

|

·

|

Being member of a cooperative

|

·

|

Location of the business

|

·

|

Availability of audited

|

|

·

|

Health status

|

·

|

Firm Performance

|

|

financial statements

|

|

·

|

Gender

|

·

|

Distance to a lending

|

·

|

Value of assets

|

|

·

|

Characteristics of the borrower

|

|

Institution

|

·

|

Availability of collateral

|

|

(caste)

|

|

|

|

|

|

·

|

Religion

|

|

|

|

|

|

·

|

Guarantor

|

|

|

|

|

2.6. Literature on AVCF

2.6.1. Gap of the Literature on AVCF

Recent studies have focused on the determinants of the sources

and amount of agricultural credit (Yadav & Sharma, 2015), and on evaluating

the access to finance at the farmers' level (Gamage, 2013). However, few

researchers have taken into consideration the contribution of financial

institutions (FIs) and the identification of the supply-side determinants of

agricultural credit (Meyer R. L., 2002; Yadav & Sharma, 2015). This could

be an area of further potential investigation, mainly, in new approaches such

as AVCF (Villalba, Venus, & Sauer, 2021).

According to Zander (2016), the research available on AVCF is

relatively scarce due to a number of major concern that restricts the knowledge

about non-bank based agriculture value chain financing. First, the hesitation

of the private sector and agri-businesses to share their information with

others due to confidentiality issues. Second, the hesitation of FIs to share

operational and performance details of their agricultural portfolio due to

confidentiality. Finally, the hesitation of analysts and authors to disclose

details on outcomes and impacts, since the initiatives are new and the results

are not sufficiently robust.

20

With respect to the adequate information on this topic, there

is a significant gap in the available literature overall. The influences of the

AVCF are little reported in the literature, even though external facilitation

needs strict monitoring of the impact of the AVCF, especially for small-scale

producers

2.6.2. Available literature on AVCF

Regarding the Types of the existing literature on AVCF, there

are three types of documents available (Zander R. , 2016):

a) Normative information and guidance

b) Descriptive documents with facts and figures

c) Anthropological and sociological studies

Concerning the studies available on the development of AVCF in

the literature, Miller and Jones (2010) discuss 5 cases of AVCF involvement; 1.

Numeric project in Kenya and Tanzania 2. Inventory credit system Niger 3.

Integrated agri-business finance model 4. Technological innovations in Kenya 5.

Integrated Agro-food in India. The analysis of actual cases and results in this

paper does not show the aspect of the implications of AVCF on agricultural or

financial sector development (Zander R. , 2016).

KIT and IIRR (2010) address the financing gaps that exist

within agricultural value chains. This book presents detailed case studies.

These include sections on results, impact, threats and challenges, and lessons

learned. Among the cases discussed we can mention; Credivida in Peru, BASIX

group in India, K-Rep Group in Kenya, Organizations supporting the soybean

value chain in Ethiopia, UCPCO and Fondo de Desarrollo Local in Nicaragua, and

Pro-rural In Bolivia.

A publication of Inter-American Development Bank (2010) has

highlighted the relationship between AVCF and local financial and agricultural

sectors. This report compared two value chains in Nicaragua (dairy and

plantains) and Honduras (plantains and horticulture) and included relative

observations on mechanisms used within the value chain financing (Coon,

Campion, & Wenner, 2010).

Another FAO publication of Da Silva and Rankin entitled

«Contract Farming for Inclusive Market Access» presented case studies

of different value chains of cacao, sugar, oil palms, and other plantations

crops which work with international markets under contract farming between lead

firms and cooperatives. This report emphasized the importance of this

instrument which is a very interesting development tool with growing

expectations for VC promoters (Da Silva & Rankin, 2013).

21

A recently published discussion paper from the Deutsches

Institut für Entwicklungspolitik, discusses the implications of the AVCF

arrangements for agricultural sector development and presents strategies that

reduce the risks for financial sector growth, with the aim of better reaching

priority segments of the rural population such as small-scale farmers and rural

micro and small enterprises (Zander R. , 2016). This paper illustrates in

detail the following 4 case studies: 1. accelerating production and

post-harvest infrastructure in Rwanda 2. Fostering AVCF in Ethiopia 3. COMPACI

project in Zambia 4. KELIKO farmer association in South Sudan.

The following table shows the different publications available

from which we have selected all the FIs that have experience in the application

of the AVCF. These FIs will be contacted for the survey later

Table 4: Number of FIs mentioned in the literature

review

|

Publication

|

Authors

|

Year

|

No. FIs

|

|

AVCF: Tools and Lessons

|

Miller and Jones

|

2010

|

45

|

|

Value Chain Finance

|

KIT and IIRR

|

2010

|

28+(25)

|

|

Financing Agriculture Value Chains in Central

America

|

Coon, Campion and

Wenner

|

2010

|

8+(27)

|

|

Agricultural finance for smallholder farmer

|

Daniela Röttger8

|

2015

|

8

|

|

Contract Farming for Inclusive Market Access

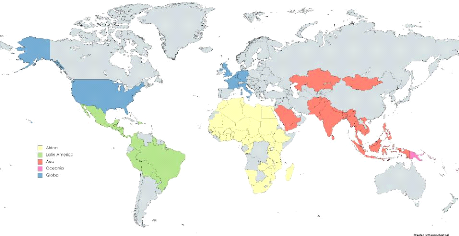

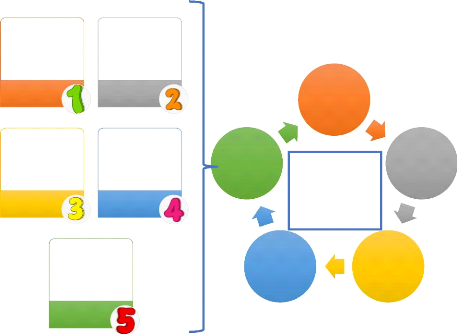

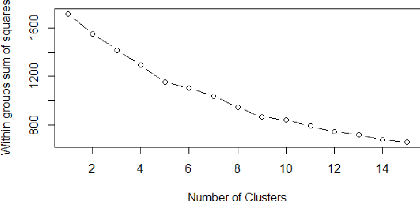

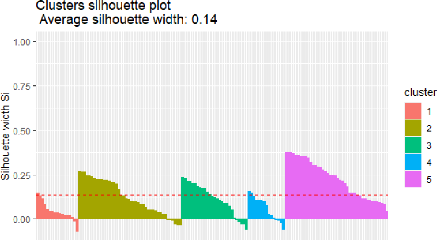

|