|

Analyzing how to shift Informal Unit of Production

(IUP) to formality:

the case of Cameroon

Ramses ZANG and Chadeney NDAPOU1

Contact:

zang_omer@yahoo.fr

Abstract

For a country like Cameroon witnessing an informal employment

rate of more than 90%, the shift towards formality requires an effective public

assistance. This paper attempts to prescribe a way by which public funds could

be less riskily and more efficiently allocated to IUPs according to their

dynamism measured here by their profitability. The methodology used in this

paper is the construction of a frame for assessing IUPs effectiveness with some

of their positive core characteristics like education attainment of the owner

and the sales, and a negative one, the costs. The main variables have been

selected through a principal components analysis. A logistic regression has

been used to estimate parameters necessary to complete the scoring equation

aimed at identifying less risky and more efficient IUPs. As a perspective, it

comes out that IUPs might be very motivated if a policy aimed at effectively

allocating them public funds according to their dynamism is put in place. They

could find more rationales to gather themselves for more effectiveness and

greater probability to benefit from these funds, expand and then get access to

bank credits.

1. Introduction

In Cameroon, the unemployment rate in 2005 was 4.4% according

to the International Labor Organization definition. Besides how impressive this

figure may appear, it hides a tremendous amount of precariousness and

underemployment. Actually, underemployment touches more than three quarters of

the potential working force in Cameroon. Underemployment and precariousness

comprise both the unemployed and the employed population earning less than the

legal minimum wage or working less than 35 hours a week. This underemployment

is essentially nurtured by the informal sector that employs more than 90% of

the actual working force. In fact, the underemployment rate was 70.6% in the

non-farming sector and 86.8% in the informal farming sector. It is important to

notice that this situation has been favored by the economic crisis of the 80s.

Moreover, many evidences now show that one of the huge unanticipated drawbacks

of the Structural Adjustment Policy focusing on the reduction of public

spending has deeply affected the labor force in the sense that it has led to

the reduction of the Government' s staff, so far the main formal employer. The

private sector was at that time too under-expanded to absorb the bounce of job

seekers. The country has therefore witnessed the development of an

uncontrollable urban informal sector and the rise of precarious jobs. It is

more than a necessity nowadays to try to cancel all this precariousness and

informality that not only entertains harsh labor conditions and poverty but

also perpetuate disconnection between public policies and people in real need.

A way of doing that is to accompany dynamic informal units susceptible to earn

the status of small formal production units to do so faster and comfortably.

Cameroonian authorities, in the global framework of fighting against poverty

have put in place in 2002 a structure, «Projet Integre d'Appui aux Acteurs

du Secteur Informel (PIAASI)» aiming at ensuring the promotion of the

informal economy. This action, managed by the Ministry in charge of labor and

professional training is translated into the financing and training of actors

of the sector in concern. Thanks to resources from the Heavily Indebted Poor

Countries Initiative, the PIAASI was launched in 2005. It was essentially

focusing on very small projects for self employment and

1 Engineers in Statistics and Economist

microenterprises like artisanal activities, very small scale

esthetics, catering, shoes repairs, farming, etc. The authors of this paper

want to show that such an action must be extended to the IUPs the most dynamic

in order to take them to the scale of small formal enterprises. With This

purpose, the present paper will realize a partition of IUPs in Cameroon using

the survey 1-2-3, phase 2 of 2005 to distinguish stagnant units from dynamic

units that could potentially evolve to become formal enterprises. We will

therefore design a set of characteristics that could allow a public policy to

efficiently finance such IUPs. We will use discriminatory procedures from SPAD

software and logistic analysis from STATA software to make available the more

relevant variables that differentiate stagnant from dynamic IUPs. Moreover, we

intend to provide a set of parameters and characteristics gathered in a scoring

equation that could allow any anonymous IUP to be appropriately ranked in each

group provided some of its characteristics.

2. Methodological issues

Methodological issues in this paper stand on the concept of

informality and the identification of dynamism amongst the IPUs through

discriminatory and multivariate analyses.

The concept of informality

The debate on a universal definition of informality is still

pending. The term «informal» was used for the first time by Hart in

1971. It has been reemployed by the ILO in its report on Kenya in 1972. This

evocation has underlined seven criterions to identify IUPs: exclusive use of

local resources, family ownership of the unit, reduced scale of the activity,

use of techniques that are essentially man power demanding, skills of the

manpower are acquired out of formal training institutions and highly

competitive markets without regulation. These characteristics were too numerous

for a single unit to meet them all. Further criterions were therefore

restricted to the scale and the lawfulness of the unit. The criterion of scale

is the most easy to mobilize because it requires just a unit to have less that

a threshold of employees (usually, 10). The scale criterion is not

appropriate for international comparisons though, and doesn't take into account

the smallness of enterprises like attorney offices, notaries, accountants that

are modern and most of the time very profitable. To avoid that insufficiency,

the criterion of legality has been settled. According to this criterion, an IUP

is the one that does not respect the law, the pending question here still

being; which laws among the numerous existing are required? This led to the ILO

combining the criterions of smallness in terms of employment and non

registration of the unit or of the regular workers. The survey 1- 2-3 that we

will use in this paper has considered informal, any activity without a tax

payer identification number and/or not handling written accounts according to

the scheme required by the law.

Measuring the economic dynamism of

IUPs

Among the possible variables like sales, numbers of employees,

etc, profits have been chosen as the variable to discriminate between the

less and the more effective. The less effective group will be

constituted of IUPs that make monthly profits which are less than the

nationwide median, the more effective being those with monthly profits which

are more than the nationwide median. The profit is defined as the difference

between sales and costs (mainly salaries and taxes). After we decided on the

discrimination criterion, the concern was now to extract from the huge database

the more relevant variables likely to explain the ranking in one group or

another. The Principal components analysis (PCA) has been operated to realize

the variable specification. The PCA like the factorial analysis are statistical

tools that summarize the variability among a set of numerous variables. In

fact, they seek to describe the variation of a given set of variables as linear

combinations of the original variables in which each linear

combination is aimed at explaining a maximum of variation of

original variables without being correlated to the other linear combinations.

Most of the time, analysts just focus on the first two linear combinations that

by definition explain most of the variability. It is therefore possible to

scatter plot the IUPs according to the two axes obtained from the first two

linear combinations and to represent the variables in the circle of correlation

comprising the above mentioned axes.

The next step was to apply the multivariate discriminatory

analysis techniques to differentiate the two groups of IUPs so that an

anonymous IUP could be ranked in the appropriate group knowing only some core

characteristics. For this purpose we both operated the so called credit scoring

techniques and the logistic regression. The credit scoring is used in several

areas like medicine, meteorology or finance, the latest using it to identify

solvable clients. It consists of performing comparison tests using the Wilks'

Lambda (£) as statistics' test on the core variables identified

through the PCA process. Its applicability requires the observance of two

hypotheses that are the equality of the covariance matrix of the two groups and

the normality of the distribution of each population group. If £

tends towards 1 its influence on the differentiation is not relevant,

in the contrary, the further it goes below 1, the more it influences

the differentiation. Mindful that the Credit score technique requires the

observance of these strong hypotheses, it is easier to cross over those

requirements by applying a logistic

p

regression. The Logit function is defined as

LogitP fi fi X

= + where designates the

i i

i = 1

coefficients, i the index of the variable, X

the variable, p the number of variables and P the probability

of being ranked in the effective group. The above equality corresponds to the

expression: P(Y=1/X=x) = 1/(1 +e-(/31x1+...+

/3pxp).

The estimation of coefficients uses the maximum likelihood.

The normality of the distributions of variables is required. We ranked an IUP

in the effective group if its probability was more than 0.5. From the

above process we could deduce the score of effectiveness defined as S(x) =

/31x1+... + /3pxp and then rank the IUP according to

their results in the scoring process.

We have deliberately chosen just to display the results

obtained from the logistic regression because they have been found more

relevant than the credit scoring method. In fact, the matrix of confusion of

the logistic regression was stronger than the credit scoring one.

3. Data and variables specification

Data were obtained from the National Institute of Statistics

of Cameroon2 and were resulting from the 2005 survey 1-2-3 which had

as objectives the follow-up of employment, informal sector and household

consumption. We used the phase 2 that focuses on the informal sector by

collecting data on the working conditions, manpower, contribution of the

informal sector to the economy and issues and perspectives of that sector. The

phase 2 is theoretically supposed to happen every four years. It will then be

possible to update the parameters of the model we are proposing according to

that periodicity.

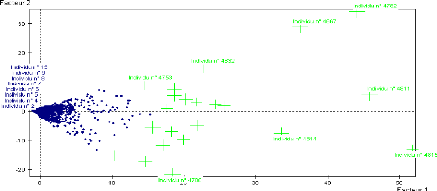

As we mentioned above, the PCA was used for the variables

specification. 4,815 IUPs were involved in the process. The first two

axes were representing 58.5% of the total variability. When plotting

the IUPs according to these two axes, the results suggested that they were

relatively very close each other as shown on the graph 1 below. In

fact almost all IUPs are surrounding the mean point.

2

www.statistics-cameroon.org

Graph 1: Two way scatter of IUPs in the factorial plan

Nevertheless, some points are found very far from the mean

point suggesting that they are witnessing a relatively high level of activity

with sales cros sing the threshold of the FCFA 1,000,000 (US$ 2,500).

Theses points are represented by crosses proportional to the size of their

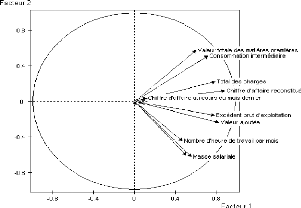

activities. Variables were also represented in the correlation circle (see

graph 2). This graph shows that almost the whole variables are very well

represented, the arrows designating each being very close to the borders of the

circle on the factorial plan. We can observe four groups of variables. The

first is the set raw materials and intermediary consumption, the

second, number of worked hours and the salaries, the third,

variables indicating the gross benefice and the fourth, sales and

costs.

Graph 2: Variables correlation in the factorial plan

We will finally keep only three variables representing each

group: the sales, the number of hours worked and the costs per month. To these

variables we will add control variables like education level of the owner, his

age and the age of the IUP.

4. Findings and Results

The dynamic of job creation in

Cameroon

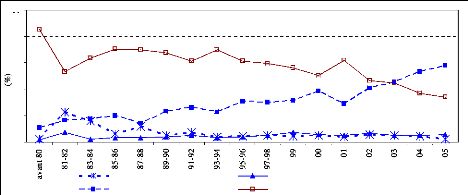

From the curves below, we can notice that the informal

non-farming sector (60%) has become since 2003 the main occupation of the

population, crossing over the farming informal sector (38%). The public and the

private formal sectors are stagnating since the 90s.

Graph 3: Job creation according to the institutional sector over

20 years

Source: NIS, Surveys 1-2-3, 2005, Phase 1

100

40

60

20

80

0

Secteur public Entreprise privée formelle

Entreprise privée informelle non agricole Entreprise

informel agricole

Structure of employment in Cameroon

Table 1: Structure of employment according to institutional

sector and the area

|

Employment

%

|

Mean age

|

Females (%)

|

Male (%)

|

Years of

di

|

Experience within h i

|

|

Urban

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Public

|

10.5

|

39.7

|

31.8

|

81.1

|

12.3

|

9.6

|

|

Private formal

|

11.8

|

36.1

|

20.4

|

79.1

|

10.9

|

5.9

|

|

Informal non-farming

|

67.4

|

31.2

|

45.4

|

66.4

|

7.0

|

4.5

|

|

Informal farming

|

10.3

|

37.2

|

57.4

|

52.0

|

5.2

|

12.6

|

|

Overall

|

100

|

33.3

|

42.2

|

67.9

|

7.8

|

6.0

|

|

Rural

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Public

|

2.6

|

39.4

|

25.8

|

79.7

|

11.3

|

7.5

|

|

Private formal

|

2.0

|

35.9

|

15.4

|

79.3

|

7.6

|

6.7

|

|

Informal non-farming

|

22.5

|

31.9

|

55.0

|

44.3

|

4.3

|

6.2

|

|

Informal farming

|

72.9

|

33.3

|

52.7

|

35.3

|

3.2

|

12.2

|

|

Overall

|

100

|

33.2

|

51.8

|

39.3

|

3.8

|

10.6

|

|

Cameroon

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Public

|

4.9

|

39.6

|

29.5

|

80.6

|

11.9

|

8.8

|

|

Private formal

|

4.7

|

36.0

|

18.9

|

79.1

|

9.9

|

6.2

|

|

Informal non-farming

|

35.2

|

31.5

|

49.8

|

56.3

|

5.8

|

5.3

|

|

Informal farming

|

55.2

|

33.5

|

53.0

|

36.2

|

3.4

|

12.2

|

|

Overall

|

100

|

33.2

|

49.1

|

47.4

|

4.9

|

9.3

|

Source: NIS, Surveys 1-2-3, 2005, Phase

1

Table 1 shows that across the country, more than one

worker out of two is a business owner

working as a self-employer or with

very few employees. In the rural area, almost one third of

the working population is family helping without effective

salaries. The working class which is the more representative in developed

countries accounts only for 8% in the whole country and 20.3% in urban area.

Not surprisingly, the formality of positions goes side by side with the number

of years of schooling.

Underemployment in Cameroon

Visible underemployment is a situation characterizing workers

unwillingly involved in less than 35 hours a week in their main activity for

reasons linked to their employer or to a bad economic situation. It was

touching 12.2% of the working class in Cameroon in 2005. It is twice higher in

the non-farming working sector than in all other sectors. It increases

according to the level of education. A high working time could be also

translated by a form of underemployment occasioned by the lowness of the

productivity. This form of underemployment is called invisible underemployment

and is usually estimated by the level of income. In Cameroon, the invisible

underemployment rate is defined as the percentage of the working class earning

less than FCFA 23,500 (US$ 65) a month for 40 hours worked a week. This rate is

estimated at 69.3% of the actual manpower. It is within the informal sector

that underemployment is more crucial with more than six persons out of 10. The

underemployment affects more the rural area than the urban area. In the

contrary of visible underemployment, invisible underemployment decreases with

the level of education. The sum of these two forms of underemployment and the

unemployment yields the global underemployment that touches three quarters of

the potential working class in Cameroon. This problem is the more critical of

the Cameroon employment issues because many trained young people declare

exercising informal jobs to survive while hoping for a more stable and better

rated job corresponding to their qualification and/or their level of

studies.

Table 2: Rates of underemployment according to institutional

sector, the gender and the area

|

Institutional sectors

|

|

Visible

|

|

|

Invisible

|

|

Overall

|

|

|

Urban

|

Rural

|

Cameroon

|

Urban

|

Rural

|

Cameroon

|

Urban

|

Rural

|

Cameroon

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Public

|

7.3

|

10.1

|

8.4

|

3.1

|

17.4

|

8.6

|

10.3

|

26.8

|

16.7

|

|

Private formal

|

6.4

|

5.6

|

6.2

|

13.6

|

31.8

|

19.0

|

19.3

|

34.2

|

23.7

|

|

Informal non-farming

|

17.1

|

23.1

|

19.9

|

54.4

|

66.8

|

60.1

|

64.8

|

77.5

|

70.6

|

|

Informal farming

|

15.6

|

7.6

|

8.0

|

70.2

|

85.7

|

84.8

|

75.1

|

87.5

|

86.8

|

|

Gender

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male

|

12.1

|

11.8

|

11.9

|

37.8

|

71.5

|

60.7

|

50.9

|

77.2

|

68.3

|

|

Female

|

18.2

|

10.5

|

12.4

|

56.6

|

85.2

|

78.2

|

70.9

|

88.3

|

83.6

|

|

Overall

|

14.7

|

11.1

|

12.1

|

45.7

|

78.6

|

69.3

|

68.3

|

83.6

|

75.8

|

Source: NIS, Surveys 1-2-3, 2005, Phase

1

Effectiveness of IUPs

The effectiveness of an IUP corresponds to its ability to

create jobs in order to raise its production and make profits. The level of

gross profit has therefore been considered in this paper to categorize IUPs.

Meanwhile, table 3 below shows other possible criterions that we could

have taken. The nationwide gross profit median is FCFA 28,000 (US$70)

per month; a very low profit which mainly characterizes IUPs in Cameroon. But

this median profit is stretched from a minimum of FCFA 82,000

(US$165) losses to a maximum of FCFA

8,899,000 (US$18,000) earnings with a standard

deviation of FCFA 199,429 (US$400). We can also notice that those with

employees are the more performing. A qualitative criterion could be settled on

that aspect if credits have to be attributed to IUPs.

Table 3: Performances of IUPs per type of occupation and per

type of area (monthly in ,000 FCFA)

|

|

Sales

|

Production

|

Added value

|

Gross profit

|

|

Mean

|

Median

|

Mean

|

Median

|

Mean

|

Median

|

Mean

|

Median

|

|

Type of occupation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Self employment

|

133.8

|

47

|

77

|

36

|

43.7

|

19

|

43

|

19

|

|

Non salary job

|

173

|

65

|

110.9

|

46

|

58.2

|

22

|

54.7

|

21

|

|

Salary job

|

704.3

|

300

|

529.9

|

200

|

328.3

|

122

|

254.3

|

85

|

|

Mixt

|

650.6

|

255

|

601.9

|

255

|

304.8

|

171

|

226.7

|

112

|

|

Overall

|

173.8

|

57

|

110.2

|

41

|

62.4

|

28

|

57

|

28

|

|

Urban area

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Self employment

|

206.5

|

90

|

112.3

|

56

|

66.9

|

34

|

65.6

|

32

|

|

Non salary job

|

283.3

|

117

|

187.2

|

84

|

96.5

|

44

|

89.9

|

38

|

|

Salary job

|

897.1

|

301

|

625

|

280

|

360.7

|

172

|

274.1

|

112

|

|

Mixt

|

683.7

|

311

|

643.7

|

311

|

326.9

|

197

|

241.1

|

120

|

|

Overall

|

275.2

|

105

|

168.3

|

69

|

95.5

|

41

|

86.5

|

37

|

|

Rural area

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Self employment

|

83.2

|

31

|

52.4

|

26

|

27.6

|

12

|

27.2

|

12

|

|

Non salary job

|

109.1

|

45

|

68.9

|

37

|

37.2

|

16

|

35.3

|

15

|

|

Salary job

|

463.5

|

200

|

411.2

|

150

|

287.8

|

100

|

229.5

|

61

|

|

Mixt

|

504.3

|

113

|

445.9

|

113

|

222.5

|

69

|

172.7

|

41

|

|

Overall

|

104.6

|

37

|

70.5

|

30

|

39.8

|

14

|

36.9

|

13

|

Source: NIS, Surveys 1-2-3, 2005, Phase

2

Table 4 displays some of the characteristics of the

two groups generated. The more effective group is in almost all aspects

averagely greater than the less effective except in terms of age of the owner

and duration of exploitation where we could not find significant

disparities.

Table 4: Group's statistics (means)

Hours worked Education Age of the duration of

last month level Sales Costs owner exploitation

|

Less effective IUPs

|

136.6

|

5.0

|

44.0

|

33.0

|

36.6

|

6.6

|

|

More effective IUPs

|

210.5

|

7.7

|

384.7

|

263.9

|

35.4

|

6.2

|

|

Overall

|

173.6

|

6.4

|

214.7

|

148.6

|

36.0

|

6.4

|

Logistic analysis

The parameters of the logistic regression are shown on

table 5. The second column provides the estimated coefficients; the

fourth one displays the probability of rejecting the nullity of the

coefficients; and the last one shows the marginal effects of every variable.

Sales, hours spent at work, costs and to a lesser extent, education levels are

all significant at a threshold of 5%. As expected, costs affect negatively the

effectiveness of IUPs; this should be interpreted cautiously though, because

great expenses sometimes mean higher production for higher sales and higher

profits. This means also that the Government can effectively alleviate (0.24)

the informal sector by reducing or canceling some of their taxes to favor their

entrance into formality. The variable that influences the most is the amount of

sales with an odd ratio of 0.25. The time spent at work is almost neutral in

terms of impact on the effectiveness. As we can notice from the last column,

marginal effects are very low for all the variables at stake.

Table 5: Parameters of the logistic regression of the

effectiveness of IUPs

S.E Wald Signif. Exp ( ) Marg. Eff.

Education level

|

0.03

|

0.01

|

5.44

|

0.02

|

1.03

|

1. 12 x 10-6

|

|

Sales

|

0.25

|

0.01

|

646.58

|

0.00

|

1.28

|

8. 34 x 10-6

|

|

Charges

|

-0.24

|

0.01

|

618.23

|

0.00

|

0.79

|

-8. 14 x 10-6

|

|

# hours at work during last month

|

0.00

|

0.00

|

42.16

|

0.00

|

1.00

|

1. 60 x 10-7

|

|

Intercept

|

-7.85

|

0.32

|

617.26

|

0.00

|

0.00

|

---

|

Number of observations = 4809 ; Prob > chi2 = 0.000; Log

likelihood = -5 17.70446; Pseudo R2 = 0.8447

Table 6 below shows that 96.9% of the IUPs have been

well ranked from the logistic regression while only 72.3% were so with the

Wilks' test approach.

|

Table 6: Confusion matrix

|

|

|

|

|

Attributed groups

Real Groups

|

Less effective IUPs

|

More effective IUPs

|

Total

|

|

Less effective IUPs More effective IUPs

|

2,346 95

|

54

2,3 14

|

2,400

2,409

|

|

Total

|

2,441

|

2,368

|

4,809

|

We can therefore easily compute for any anonymous IUP the score

of effectiveness S;

S = 0.03Education + 0.25Sales - 0.24Costs,

and rank it according to it final score in order to efficiently

allocate them credit for their expansion to a formal activity.

5. Discussion

Cameroon is witnessing a historical increase in informality

mostly touching the non-farming sector. Its contribution to the GDP has evolved

from 22% in 1993 to almost 50% 12 years later. This sector provides 90.4% of

jobs in the country. Most of these jobs are precarious and casual. One of the

biggest issues that this sector faces is that, it doesn't have access to the

credit market; this hampers its process of comfortably evolving to the formal

sector. The PIAASI has an approach of promoting the informal sector by

allocating credits to selfemployment projects. We analyzed through this paper

how it would have been more efficient for the PIAASI to allocate funds to IUPs

according to their dynamism in order to accompany them in the formal sector

which is legally more advantageous (protection, credit access, accountability,

sales...) and in the long run, economically safer than the informal sector.

These advantages are mostly ignored by informal sector operators. Through the

scoring of IUPs, the Government could allocate them promoting funds that would

encourage small IUPs to gather and be more efficient in order to fulfill the

requirements and benefit from that unprecedented opportunity. The sectors of

the microfinance and banking could therefore treat more respectfully the IUPs

which otherwise pay huge interests for very few loans due to the high level of

risk that constitute their portfolio.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Institute of Statistics (NIS) of Cameroon

which has granted us the data

and supervised us in partnership with the

«Institut Sous-regional de Statistiques et

d'Economie Appliquee» (ISSEA). We also thank Mr. GOUNE

TEKOMBONG Russel Romeo for his critical reading of this paper.

References

Lantier B., L'économie informelle dans le tiers

monde, collection reperes, Edition La Découverte, Paris, 1994 ;

Bry X., Analyses factorielles multiples, Economica,

Paris, 1996 ;

INS, Rapport principal de l'enquête sur l'emploi et le

secteur informel au Cameroun, Janvier 2006 ;

Lachaud J.-P., Le secteur informel urbain et

l'informalisation du travail en Afrique : rhétoriques : le cas de la

Côte d'Ivoire ;

Jacquet P., A l'école du secteur informel dans les

pays en développement, Le monde du 26 juin 2007 ;

Barthelemy P., Le secteur urbain informel dans les pays en

developpement : une revue de littérature ;

SAPORTA G., Probabilité, Statistique, Analyse des

données, Éditions TECHNIP, Paris 1997.

BIKOUN B. M., 71 millions d'appui au secteur informel,

Quotidien Mutations du 20 octobre 2006.

|