MONETARY POLICY STRATEGY IN RWANDA

By

Serge Musana Mukunzi

Supervisor: Nicola Viegi

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the

Master's degree of commerce (Economics).

University of Kwazulu-Natal,

Durban, 2004

DECLARATION

I declare that this is my own work, except where acknowledged

in the text, and has been submitted or a degree at any other university.

.....................................................

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DECLARATION.....................................................................................i

TABLE OF

CONTENTS...........................................................................ii

LISTE OF

TABLES.................................................................................iv

LISTE OF

FIGURES................................................................................v

DEDICATION.......................................................................................vi

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS.........................................................................vii

ABSTRACT........................................................................................viii

Chapter 1:

INTRODUCTION.....................................................................

1

Chapter 2: THEORETHICAL FOUNDATION OF MONETARY

POLICY...............5

2.1: Objective of monetary

policy.................................................................5

2.2: The instruments of monetary

policy.........................................................7

2.3: Monetary policy

strategies.......................................................

............10

2.3.1: Choosing and using a

target............................................................... 11

2.3.2: Monetary policy

rules......................................................................

12

2.3.2.1: Exchange rate

rule........................................................................13

2.3.2.2: Money supply

rule........................................................................14

2.3.2.3: Nominal GDP target

rule.................................................................16

2.3.2.4: Inflation targeting

rule....................................................................18

2.3.2.5: Taylor

rule.................................................................................21

Chapter 3: MONETARY POLICY IN

RWANDA.............................................23

3.1: Macroeconomic

background.................................................................23

3.2: Monetary and exchange rate policy

management.........................................25

3.2.1: Monetary

policy.............................................................................26

3.2.2: Exchange rate

policy........................................................................29

Chapter 4: ILLUSTRATION OF MONETARY STRATEGY

BY MEANS OF

MODEL.........................................................................31

4.1: Empirical

analysis.............................................................................34

4.1.1: Reaction function for

Rwanda.............................................................34

4.1.2:

Methodology..................................................................................36

4.1.2.1:

Data...........................................................................................36

4.1.2.2 Time series properties of the

data........................................................37

4.2: Estimation

results..............................................................................40

Chapter5: CONCLUSION AND

SUGGESTION.........................................................................47

BIBLIOGRAPHY..................................................................................49

APPENDIX..........................................................................................54

LISTE OF TABLES

Table 3.1: Inflation objective and

Inflation observed in

percentage...................................................................................27

Table 3.2 Monetary stock aggregate(M2) Net External Asset

(NEA) and

Net Interior Asset (NIA)In

percentage.........................................................29

Table 4.1 Unit root test-levels of

variables................................................... 38

Table 4.2 Unit root tests of the first

difference............................................... 38

Table 4.3 Ordinary Least squares

estimation of equation

4................................................ .........................40

Table 4.4 Ordinary Least squares

Estimation of equation

5.........................................................................42

LISTE OF FIGURES

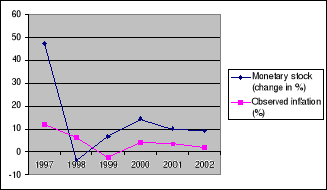

Figure 3.1: Annual growth of monetary stock aggregate

M2 and

inflation:1997-2002............................................................................28

DEDICATION

This dissertation is dedicated to the Musana family.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

My thanks goes to my academic supervisor Dr Nicola Viegi for

his guidance, inspiration, comments and criticism which inspired many ideas and

produced some very satisfying solutions.

I have profound gratitude to Professor Rwigamba Balinda, the

Rector of Kigali Independent University, for sponsoring my post graduate

studies at the University of Kwazulu-Natal.

Thanks goes to my friends and colleagues in the economic

department for making my student life enjoyable.

Thanks also goes to my family and all friends for their

encouragement and support which they have given me during my studies.

Last but not least, special thanks goes to my Lord Jesus

Christ for all the Blessings, which, I enjoy in this life.

ABSTRACT

The aim of this dissertation is to study how monetary policy

is conducted in Rwanda. The task has been accomplished by designing and

estimating a Taylor rule, monetary policy reaction function for the National

Bank of Rwanda over the period 1997-2001.

Applying Ordinary Least Squared (OLS) on the time series data,

we test whether the Central Bank in Rwanda reacts to changes in the inflation

gap, the output gap and the exchange rate. The results of the study show that

the Central Bank of Rwanda has had a monetary policy over the years with the

monetary stock aggregate (M1) as the principal instrument. The results also

show that the Central Bank of Rwanda reacted by giving much importance to the

exchange rate than to inflation and neglected the output.

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

In recent years, Central Banks appear to have conducted

prudent monetary policies in several countries. In such a context, the role of

monetary policy as a stabilisation policy is becoming more powerful and well

determined. As argued in Blinder (1998), Central Banks have never been more

powerful than now. Monetary policy has become the principal means of

macroeconomic stabilisation, and in most countries it is entrusted with the

responsibility of an independent Central Bank.

From the experience of developed economies in the world which

exhibit strong economic management, various countries in developing economies

have undertaken economic reforms consisting essentially of a set of

market-oriented economic policies intended to readjust the economy to the

liberalisation as well as bringing about an institutional reorganisation.

In the sub-Sahara African context, reforms increased

significantly in the 1990s. The broad strategy has been the emphasis placed on

the policy programs supported by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the

World Bank, including among others fiscal reforms, liberation of exchange

restriction and the adoption of indirect instrument of monetary policy,

market-based interest policies, and so on. (IMF, December 2000).

Rwanda is no exception to this situation. Rwanda's economy is

very small and open, heavily reliant on the export of few major products,

especially coffee and tea. In addition it is also very reliant on imports for

most of its consumables.

The destruction of the economic base that took place during

the civil war period (1990-1994) forced the authorities to begin a process of

economic liberalisation: to turn away from the situation of control, regulation

and state command and turn towards more market related policies since 1994. In

1997, Rwanda embarked on a program of sustainable economic growth. A revised

Central Bank statute underpinning the National Bank of Rwanda's independence in

conducting the country's monetary policy was adopted. The period of

1998/99-2000/2001 was characterized by an enhanced structural adjustment

facility program supported by IMF and World Bank. Based on this strategy, the

macroeconomic objectives included an annual average real Gross Domestic Product

(GDP) growth of 8 percent a year during the period 1998-2000; and a reduction

in inflation to 5 percent by end 1999. In the period 1999-2002, the

macroeconomic objectives were to achieve an annual real GDP growth of 6%, while

keeping inflation at or below 3%.

In such program, the monetary policy played a central role in

producing macroeconomic stability. It stated that monetary and credit policies

would aim at further reducing the rate of inflation, and the authorities would

continue to monitor development in both reserve money and broad money closely

(IMF and Rwanda 1995/2002).

What it is clear from the Rwandan Central Bank behavior is

that an achievement of the inflation target seems to be a fundamental goal of

the monetary authority. On the basis of all the macroeconomic objectives

mentioned above, Rwandan monetary authorities seem to assess the performance of

monetary policy rules in terms of their effect on inflation and output. Such an

assessment can be based on a situation in which the Central Bank refers to an

equation, which is intended to establish the goal that has actually been

influencing the actions of the Central Bank. One could interpret such behavior

as being approximated by a particular rule referred to as the Taylor rule. In

such a rule, monetary policy is adjusted in response to the deviation of

inflation from its target value and the deviation of output from potential.

More than five years have passed since the monetary policy

was given a central role in maintaining macroeconomic stability and a new

statute has provided rule for monetary policy objectives and Central Bank

independence. Enough observations have become available to perform an

assessment of the Rwanda Central Bank's conduct of monetary policy based on

choosing a rule and then using a model of the economy to examine how the

economy would have behaved under the rule.

The objective of the thesis is thus, to attempt to

approximate the policy behavior of the Rwanda Central Bank by estimating a

variant of the Taylor rule for Rwanda. In this specific model, the dependent

variable is the monetary base that the Central Bank is assumed to control,

while the explanatory variables are those that are assumed to affect Rwanda

Central Bank's behavior. By attempting to measure the policy behavior, the

question that arises is what was the Central Bank really reacting to? Or in

other words, which targets did the Central bank actually follow?

More specifically, the study aims to:

- Review the literature on the theoretical foundation of

monetary policy: examining the process of monetary policy and describing

monetary policy strategies

- Examine the conduct of monetary policy in Rwanda

- Describe the monetary policy strategy in Rwanda by means of

a model. That is, a Taylor Rule monetary policy reaction function applied to

Rwanda and to interpret the estimated results in the context of the Rwandan

economy.

The Taylor Rule has been considered as a representation of

Central Bank behavior in various countries. It provides information about the

responsiveness of the monetary policy instrument to the monetary variables.

Therefore, estimating the policy behavior of the Rwanda Central Bank and

determining the target the Central Bank followed, is essential to the different

policy implications, especially to the implementation of an accurate and

successful monetary policy.

The structure of the study is as follows:

Chapter 1 is an introduction. Chapter 2 presents the

theoretical foundation of monetary policy and describes the process of monetary

policy and monetary policy strategies focusing on the discussion about the main

rules for monetary policy. Chapter 3 presents the monetary policy in Rwanda and

describes the way the National Bank of Rwanda formulates and carries out its

monetary policy. It also shows exchange policy management and its relationship

to the monetary policy. Chapter 4 presents an illustration of the monetary

policy strategy by means of a model and focuses on estimating a Taylor-type

monetary reaction function for Rwanda. This chapter also covers the

methodology, including the estimation results and its analysis. Finally in

chapter 5, a conclusion and suggestion are provided.

CHAPTER 2: THEORETICAL FOUNDATION OF MONETARY

POLICY

2.1 THE OBJECTIVES OF MONETARY POLICY

Broadly speaking, the objective of monetary policy is to

influence the performance of the economy as reflected in factors such as

inflation, economic output and employment. It works by affecting demand across

the economy in terms of people and firms willingness to spend on good and

services (Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, 2004).

In such context, the main goal of any monetary policy is to

maintain stability in the broadest sense. Wallich (1982: 45) explained that by

helping to promote price stability and to avoid recession monetary policy

contributes to a framework within which the market can operate with greater

confidence. According to Mishkin (1997) six basic goals are continually

mentioned by Central Banks when they discuss the objective of monetary

policy:

- High employment level

- Economic growth

- Price stability

- Interest- rate stability

- Stability of financial markets

- Stability in foreign exchange rate markets.

In general, a high employment level has a strong link with a

sustainable output and this relationship makes the employment an important

objective. Indeed, it can be considered that when unemployment is high,

resources and workers are not sufficiently used in the economy and this results

in a low output.

The goal of economic growth is related to the one of

employment. Indeed, the economy is characterised by business cycles in which

output and employment are above or below their long term levels. The role of

monetary policy consists of affecting the output and the employment in the

short term. For example, when demand weakens and there is a recession, the

Central Bank can stimulate the economy temporarily and help push it back toward

its long term level of output by lowering interest rates.

The goal of price stability is also most desirable. This can

just be illustrated by the fact that persistent attempts to expand the economy

beyond its long term growth path will result in capacity constraints and will

lead to higher inflation without lowering unemployment or increasing output in

the long term (Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, 2004). Dornbusch, Fisher

and Startz (2001) show in the same way how the costs of high inflation are easy

to see: in countries where prices increase all the time, money no longer a

useful medium of exchange, and sometimes output drops dramatically.

According to Mishkin (1997: 476), the goal of interest-rate

stability, stability of financial markets and stability in foreign exchange

markets can be shown in short as the following:

Interest- rate stability is important because fluctuations in

interest rates can lead to uncertainty in the economic environment and disrupt

the plan for the future. Concerning the stability of financial markets, it is

known that financial crises can interfere with the ability of financial markets

to channel funds to people with productive investment opportunities, resulting

in a sharp reduction in economic activity. Having a stable financial system in

which financial crises are avoided is an important goal for a Central Bank.

Finally, the stability in foreign exchange markets has become

a major consideration of the Central Bank given the increase in international

trade and the increase in international integration.

Not all of those goals can be pursued by a given Central Bank.

Each one has to choose which goals they consider most important and vital to

their economic realities. However, when Central Banks have to decide about

which specific objectives to adopt, some conflicts among goals create veritable

difficulties. Mishkin (1997) explains that although many of the goals mentioned

are consistent with each other, this is not always the case. The goal of price

stability often conflicts with the goals of interest-rate stability and high

employment in the short term.

When all these bank's objectives are decided upon, the next

question becomes what instruments or tools does the Central Bank need to put

into operation and how useful are these tools?

2.2 THE INSTRUMENTS OF MONETARY POLICY

After selecting monetary policy objectives, Central Banks make

use of various monetary policy instruments at their disposal. Fundamentally

these instruments allow the Central Bank to stimulate or slow down the economy

by influencing the quantity of money and credit the banks can provide to their

customers through loans. Two types of monetary instruments are generally

classified, namely indirect and direct policy.

According Gidlow (1998), the indirect policies are considered

to be actions taken by the Central Bank whereby it achieves its monetary policy

aims by encouraging market participants to take particular actions in terms of

their lending and borrowing behavior. These actions may be the result of price

and interest rate incentives or disincentives brought about in the financial

market. The direct policy instruments on the other hand refer to the measures

taken by Central Bank that seek to attain the aims of monetary policy by means

of certain rules prescribing the behavior pattern of banks and possibly other

financial institutions. The indirect instrument is also considered as

market-oriented whereas the direct instrument is a non-market-oriented. Meyer

(1980) agreed that monetary policy instruments are generally classified as

either general or selective controls. General controls have their primary

effect on either the net monetary base or the size of the money multiplier.

These include open market operations, changes in reserve requirements, and

changes in the discount rate. Selective controls on the other hand, have their

primary influence on the allocation of credit among alternative uses. The

examples of selective controls include margin (or down payment) requirements

for loans to acquire securities and interest rate ceilings on rates paid by

banks on savings accounts or charged by banks on loans. Gidlow (1998) provided

as an example of direct policy instruments, the case of instructions sent to

banks under which the latter are requested not to exceed a certain amount of

lending to domestic private sector borrowers as specified period, and

instructions that banks must not quote interest rates above or below a certain

maximum or minimum level on their various credit and deposit facilities made

available to customers. Alexander et al (1995:14) also provided an interesting

explanation about direct and indirect policy instruments. They showed that the

term «direct» refers to the one- to one correspondence between the

instrument (such as credit ceiling) and the policy objective (such as a

specific amount of domestic credit outstanding). Direct instruments operate by

setting or limiting either prices (interest rates) or quantities (amounts of

credit outstanding) through regulations, while indirect instruments act on the

market by, in the first instance, adjusting the underlying demand for, and

supply of bank reserves. Based on these descriptions, it can be noted that both

types of policy instruments play an important role in economic activities.

However, direct and indirect instruments do not have the same effectiveness in

improving market efficiency in the same economic environment. As has been

specified previously, the most common direct instruments are interest rate

controls, credit ceilings and directed lending. Alexander et al (1995: 15)

argued that «direct instruments are perceived to be reliable, at least

initially in controlling credit aggregates or both the distribution and the

cost of credit. They are relatively easy to implement and explain and their

direct fiscal costs are relatively low. They are attractive to governments that

want to channel credit to meet specific objectives». In countries with

very rudimentary and noncompetive financial systems, direct controls may be the

only option until the institutional framework for indirect instruments has been

developed. The same authors also showed the disadvantages of direct

instruments. These consist of the fact that credit ceilings are based on

amounts extended by particular institutions and therefore they tend to ossify

the distribution of credit and limit competition, including the entry of new

banks. All those advantages lead to the conclusion that direct instruments

often lose their effectiveness because economic agents find means to circumvent

them.

Three main types of indirect instrument are mentioned:

-Open market operations

-Reserve requirements,

-Central Bank lending facilities

The open market operations are often seen as the most

important monetary policy tool because they are the primary determinants of

changes in interest rates and the monetary base and are the main source of

fluctuations in the money supply (Mishkin, 1997).

The way this instrument influences the economy can be seen

from purchase or sale of financial instruments by the Central Bank. Open market

purchases expand the monetary base, thereby raising the money supply and

lowering the short-term interest rates. Conversely, open market sales reduce

the reserves of the banking system, reducing the ability of banks to lend and

invest, and limiting the amount of funds available for the economy to use

(Federal Reserve System and Monetary Policy, 1979).

Open market operations are also based upon dynamic defensive

operations; dynamic operations are those taken to increase or decrease the

volume of reserves in order to ease or tighten credit. Defensive operations, on

the other hand, are those taken to offset the effects of other factors

influencing reserves and the monetary base.

Another interesting indirect monetary policy tool concerns the

changes in the reserve requirements. This consists of obliging banks to hold a

specified part of their portfolios in reserves at the Central Bank (Alexander

et al, 1995). This instrument affects the money supply by causing the money

multiplier to change.

Lastly, the Central Bank's lending facilities it is an

indirect instrument, which is often well known as discount policy. The discount

policy involves changes in the discount rate which affects the money supply by

affecting the volume of discount loans and the monetary base. A rise in

discount loans adds to the monetary base and expands the money supply whereas a

fall in discount loans reduces the monetary base and shrinks the money supply

(Mishkin, 1997).

Once all the instruments mentioned above are well applied, the

results easily seen in the level of economic activity since those instruments

influence the growth of the money supply as well as other financial

variables.

However, it is also worth noting that by using indirect

instruments, the Central Bank can determine the supply of reserve money in the

long term only under a fully flexible exchange rate regime. Even under a pegged

or managed exchange rate regime, however, Central Bank transactions affect

reserve money, at least in the short term. These transactions affect bank's

liquidity position, which results in adjustments to interbank, money market,

and bank loan and deposit interest rates to re-equilibrate the demand for, and

the supply of, reserve balances (Alexander et al, 1995).

2.3 MONETARY POLICY STRATEGIES

Having identified the instruments available for active

monetary policy implementation, it is important to understand the current

conduct of monetary policy. The latter needs to be operated within a

well-defined independent Central Bank.This means simply to provide the

authorities of Central Banks with the power to determine quantities and

interest rates on its own transactions without interference from government

institutions (Lybeck, 1998 quoted in Worrel, 2000). Similarly, Blinder (1998)

shows that Central Bank independence means two things: Firstly, that the

Central Bank has the freedom to decide how to pursue its goals, and secondly,

that its decisions are very difficult for other branches of government to

reverse. This implies that an independent Central Bank needs to be free of the

political pressures that influence other government institutions. This is

particularly important when a Central Bank needs to target inflation, exchange

rates or the monetary base for example. On this basis, an important point to

analyse could be the way Central Banks process before following a given

strategy.

2.3.1 Choosing and Using a Target

As is already known, in conducting monetary policy, Central

Banks have the responsibility to achieve certain goals or final objectives. The

latter could be the inflation rate, the GDP and others. According to Mishkin

(1997) the strategy can be explained as follows: «after deciding on its

goals, the Central Bank chooses a set of variables to aim for called

intermediate targets such as monetary aggregates, interest rates etc. which

have a direct effect of the goals. The Central Bank's policy tools do not

directly affect these intermediate targets. Alongside this, the Central Bank

chooses another set of variables to aim for, called operating targets or

instruments among others reserve aggregates or interest rates which are more

responsive to its policy tools» (Mishkin, 1997: 478) In more general

terms, Mishkin argued that the main reason for trying to achieve its goal by

using intermediate and operating target, is simply to allow the Central Bank to

judge whether its policies are on the right path and to make mid-course

corrections, rather than waiting to see the final outcome of its policies.

The process starts from Central Bank policy tools and directly

affects the operating targets, which in their turn affect the intermediate

targets, and finally the latter affect the goals. As has been specified above,

the intermediate targets comprise monetary aggregates and interest rates. In

practice three criteria are suggested for choosing one target between them. The

three criteria can be summarised briefly as follows:

- Measurability: quick and accurate measurement of an

intermediate target variable is necessary because the intermediate will be

useful only if it signals when policy is off track more rapidly than the

goal.

- Controllability: The good intermediate target is the one on

which the Central Bank must be able to exercise an effective control.

- Predictable effect on goals: the goals must have a close

link with intermediate target chosen. (Mishkin, 1997:482).

The same criteria remain valid about choosing the operating

targets. A preferable operating target must have a more predictable impact on

the most desirable intermediate target.

The strategy described above is not, of course the only one

that allows a well conducted of monetary policy. In addition, Central Banks

have increasingly sought to reach their objective of macroeconomic stability

through the adoption of certain principles known as rules for monetary policy.

2.3.2 Monetary Policy Rules

According to Taylor (1998) the monetary policy rule is defined

as a description, expressed algebraically, numerically and graphically-of how

the instruments of policy such as the monetary base or federal funds rate,

change in response to economic variables. Taken in a general sense, a rule can

be defined as «nothing more than a systematic decision-making process that

uses information in a consistent and predictable way» (Taylor, 1998:2).

The concept of monetary policy rule is the application of this principle in the

implementation of monetary policy by the Central Bank (Poole, 1999). Svensson

(1998) defines a monetary policy rule simply as a prescribed guide for monetary

policy conduct.

In policy conducted by rule, policymakers announce in advance

how the policy will respond in various situations, and commit themselves to

following through. Taylor (1998) notes that one monetary policy rule can be

said to be better than another monetary policy rule if it results in better

economic performance according to the same criteria such as inflation or the

variability of inflation and output.

In the following pages, various economic rules such as the

Exchange Rate Targeting Rule, the Money Supply Rule, GDP Targeting Rule,

Inflation Targeting Rule and Taylor Rule will be discussed in terms of their

abilities to guide Central Bankers.

2.3.2.1 Exchange Rates Rule

Exchange rate regime considerations play a strong role in

influencing monetary policy in a country. The rate of exchange means the price

of one currency in comparison with another currency. Mishkin (1997) argued that

«if a Central Bank does not want to see it currency fall in value, it may

pursue a more contractionary monetary policy and reduce the money supply to

raise the domestic interest rate, thereby strengthening its currency. Similarly

if a country experiences an appreciation in its currency, domestic industries

may suffer from increased foreign competition and may pressure the Central Bank

to pursue a higher rate of monetary growth in order to lower the exchange

rate» (Mishkin, 1997: 523).

The two most noted exchange rates regimes, fixed and floating

exchange rates tend to be extended from pegs to target zones, to floats with

heavy, light, or no intervention.

Initially, in a fixed exchange rate system, the exchange rates

are determined by the governments and Central Banks rather than the free

market, and are maintained through foreign exchange market intervention

(Dornbusch, Fisher and Startz, 2001). On the other hand, the same author

explains that the floating exchanges system is a system in which exchange rates

are allowed to fluctuate with the forces of supply and demand. The terms

flexible and floating rates are used interchangeably.

When it is taken into account that interventions can be made

from the flexible exchange rate depending on whether there is a need to get the

exchange rate floated with heavy or light intervention, as noted above, a third

way classification named the intermediate exchange rate system can be

mentioned. This rate is taken as floating rates, but within a predetermined

range

Accordingly, distinction is drawn between on the one hand,

dirty floating which is a flexible exchange rate system in which the Central

Bank intervenes in foreign exchange markets in order to affect the (short-term)

value of its currency and on the other hand, clean floating which is a flexible

exchange rate system in which the Central Bank does not intervene in foreign

exchange markets (Dornbusch, Fisher and Startz, 2001).

In the conduct of monetary policy based on exchange rate

target a major trading partner country needs to be selected and then a range of

values of the domestic currency to that country needs to be set. The major

partner retained should be characterised by a stable economy with low

inflation. The approach consists of maintaining the exchange rate at a target

range. This situation makes money supply endogenous because the Central Bank

needs to provide the foreign exchange or domestic currency demanded within the

set targets (Musinguzi and Opondo, 1999).

2.3.2.2 Money Supply Rule

Some economists, called monetarists believe that fluctuations

in the money supply are responsible for most large fluctuations in the economy.

They argue that slow and steady growth in the money supply would yield stable

output as well as stable rises in employment, and prices (Mankiw, 2000). This

view has been expressed in many works in terms of the quantity theory following

Fisher's equation of exchange.

From Fisher's equation:

MV=PY

Where M is the money supply, V is velocity, P the price level

and Y the real output level.

The term on the right (PY) is therefore nominal income or

nominal output.

Dynamizing the Fisher equation into growth rates:

(dM/dt)/M + (dV/dt)/V = (dP/dt)/P + (dY/dt)/Y

Or

gM + gV = gP + gY

where gM = (dM/dt)/M, etc.

The equation of exchange holds by definition. The quantity

theory is reached by only adding certain assumptions about what is the cause

and what is the effect.

From the above equation thus, assumption are imposed:

- Nominal money M is assumed to be exogenous and considered

under the full control of the Central Bank,

- Velocity is assumed constant,

- The aggregate nominal demand component is assumed to cause

changes in nominal income (causality runs from MV to PY),

- Output Y is fixed at the full employment level.

If velocity is assumed to be constant, gV = 0, and

causality is held as in the third assumption, then movements in nominal output

(PY) are driven by movements in the supply of money (M). If real output is

assumed to be constant at the full employment level, and gY = 0,

then

gM = gP, meaning that money supply

growth feeds entirely into price inflation. As real variables (velocity and

output) are unchanged by an increase in the money supply, the quantity theory

thus claims that money is neutral (at least in the long-term).

When some assumptions are relaxed, especially by allowing for

output growth, gY ? 0 and changes in velocity, gV ? 0,

then these growth rates are relatively stable and predictable. In other words,

output is assumed to grow at a stable rate of resource growth while velocity is

assumed to increase at some relatively stable rate of institutional evolution.

Similarly,

gM - (gY - gV) =

gP so that inflation is driven by the degree to which money supply

growth exceeds the term (gY - gV) which means output

growth minus velocity growth. As the stability assumption implies that the term

(gY - gV) is constant, then, once again excess money

supply growth above this determines the inflation rate.

(www.cepa.newschool.edu/hot/essays/monetarism/policyhtm-39lc)

In practice, much of Friedman's assumptions were criticised.

For instance, the assumption of constant or stable velocity is considered as

not realistic. From empirical evidence, velocity may be subject to

unpredictable fluctuations caused by unpredictable changes in institutional

factors. Consequently, if velocity is not stable, the policy is not useful

since its effects will be unpredictable.

In addition, Mankiw (2000) argued that «although a

monetarist policy rule might have prevented many of the economic fluctuations

the world has experienced historically, most economists believe that it is not

the best possible policy rule. Steady growth in the money supply stabilizes

aggregate demand only if the velocity of money is stable. But sometimes the

economy experiences shocks, such as shifts in monetary demand that cause

velocity to become unstable» (Mankiw, 2000: 397). As a result, several

economists think that a policy rule should allow the monetary supply to adjust

to various shocks to the economy.

2.3.2.3 Nominal GDP Target Rule

The lost of reliability of monetary supply as a policy rule,

led economists to think that nominal GDP targeting might be a good fundamental

guide for policy. The idea argued that Central Bank should target nominal GDP

using one of several policy rules. Such a rule would specify how the Central

Bank should adjust to affect a short-tem interest rate in response to

deviations in nominal GDP from target (Clark, 1994).

One of the most important reasons why the monetary aggregates

rule is less reliable is nothing more than the fact that its relationship with

prices and output have deteriorated, apparently in response to financial

deregulation and innovation (Judd and Trehan, 1992 as quoted in Judd and

Motley, 1993).

The way the nominal GDP targeting rule works can be explained

as follows:

«Under this rule, the Central Bank announces a planned

path for nominal GDP. If nominal GDP rises above the target, the Central Bank

reduces money growth to limit aggregate demand. If it falls below the target,

the Central raises money growth to stimulate aggregate demand» (Mankiw,

2000:397).

Mathematically, Judd and Motley (1993) explained a simple way

to calculate the channel of influence from nominal GDP growth to inflation. The

following is the detail of their explanation:

(1) ?P = ?X - ?Y where ?P, ?X, and ?Y represent the annualized

growth rate of the implicit GDP deflation, nominal GDP, and real GDP,

respectively. The formula states that inflation is equal to the difference

between growth in nominal and real GDP. In the long-term, real GDP growth can

be approximated by a trend rate that is determined by real factors including

the growth in labour, capital, and productivity, and thus is largely

independent of nominal GDP growth. The result of this is that, any given growth

rate of nominal GDP can be translated into a corresponding inflation rate in a

simple way. The example mentioned is that trend (or potential) real GDP growth

is commonly estimated at around 2%, so that a 5% growth rate of nominal GDP

would fix long-term inflation at around 3%. Judd and Motley(1993) proposed in

the same sense that:

«Since the growth rate of nominal GDP is equal to the

growth rate of money (?m) plus the growth rate of velocity (?V), targeting

money can be seen as an indirect method of targeting nominal GDP» (Judd

and Motley, 1993: 4).

(2) ?X = ?m +?V

Putting these definitions together yields:

(3) ?P = ?m + ?V - ?Y

As long as trend velocity growth is stable, any given

long-term growth rate of money can be translated into a long-term inflation

rate in a straightforward manner. When the velocity of M2 was

stable, the relationship between M2 and inflation was particularly

simple, since historically, the trend growth rate of M2 velocity was

zero. Thus, for example, a 5% growth rate of M2 would produce a 5%

nominal GDP growth and a 3% rate of inflation in the long run. However, when

the velocity is unstable, direct nominal GDP targeting has the advantage that

it is not adversely affected by unpredictable swings in velocity. In effect,

nominal GDP targeting is a way to circumvent problems with the velocity of

money in conducting monetary policy.

2.3.2.4 Inflation Targeting Rule

Inflation targeting has been adopted as the framework for

monetary policy in a number of countries over the past decade. The existing

body of literature into this area shows that during the 1990's, New Zealand,

Canada, the UK, Sweden and Australia have shifted to that policy regime

(Svensson, 1998). In the general sense, under the inflation target rule, the

Central Bank would determine a target for the inflation rate (usually a low

one) and then adjust the money supply when the actual inflation deviates from

the target (Mankiw, 2000).

Several sources of literature in the area of monetary policy

show that the most important interest of any Central Bank is the desire for

price stability. One of the main reasons for that is simply that a key

principle for monetary policy is that price stability is a means to an end: it

promotes sustainable economic growth (Mishkin and Posen, 1997). In all of this,

Mishkin and Posen argued that a goal of price stability requires that monetary

policy be oriented beyond the horizon of its immediate impact on inflation and

the economy.

Mathematically speaking, Svensson (1999) defines inflation

targeting as an equation where target variables are involved. More

specifically, in inflation targeting, the target variable is inflation in the

loss function.

The equation can be expressed as follows:

Lt = ½ [(Ït -

Ï*) 2 + ëYt2]

Where Ït represents inflation in period t,

Ï* is the inflation targeting, Yt is the output gap

and ë is the relative weight on output-gap stabilization.

When ë = 0 this means that only inflation enters the

equation, the loss function is called strict inflation targeting whereas the

case when ë > 0 and the output gap enters the loss function is called

flexible inflation targeting. In most studies that have concentrated on

explaining the implementation of inflation targeting it has been shown that to

set the inflation target too low is risky because there is the possibility of

driving the economy into deflation with price levels falling unrealistically.

On the other hand, there is also the risk of allowing the start of an upward

spiral in inflation expectations and inflation.

Mankiw (2000) shows that in all countries that have adopted

inflation targeting, Central Banks are left with a fair amount of discretion.

Inflation targets are usually set as a range rather than a particular number.

The same author pursues the argument that the Central Bank is sometimes allowed

to adjust their targets for inflation, at least temporarily, if some exogenous

event (such as an easily identified supply shock) pushes inflation outside of

the range that was previously announced.

It is also important to note that there are certain

discussions which debate whether inflation targeting is a monetary policy rule

or not. Indeed, while Svensson regards inflation targeting as a monetary policy

rule, Bernanke and Mishkin (1997) and King (2003) show that inflation targeting

in practice is not a rule but it is a framework for monetary policy. This is

because, technically inflation targeting does not provide simple and mechanical

operating answers to the Central Bank.

According to the above authors, inflation-targeting allows the

Central Bank use all related information and structural economic model's to

decide their monetary policy and achieve their targets. Like this, the

inflation targeting should be taken as a framework for monetary policy.

The targeting of inflation has many important advantages in

principle as well as in practice. Mankiw (2000) explains that setting the

inflation target has a political advantage that is easy to explain to the

public. This is because when a Central Bank has announced an inflation target,

the public can more easily judge whether the Central Bank is meeting that

target. It therefore increases the transparency of monetary policy and, by

doing so, makes Central Bankers more accountable for their actions.

Considering the above advantages of inflation targeting, it is

well recognized that the success of inflation targeting cannot only be the duty

of the Central Bank: relevant fiscal policy and appropriated monitoring of the

financial sector are essential to its success.

However, apart from the success, inflation targeting also has

some disadvantages. Mishkin states these as follows:

«Because of the uncertain effects of monetary policy on

inflation, monetary authorities cannot easily control inflation» (Mishkin,

1997: 14). He supports this statement further by proposing that «it is far

harder for policymakers to hit an inflation target with precision than it is

for them to fix the exchange rate or achieve a monetary aggregate target»

(Mishkin, 1997: 14).

Another negative side of inflation targeting quoted is that

time delay of the effect of monetary policy on inflation are very long (the

estimates are in excess of about two years in industrialized countries). Thus,

in such case much time must pass before a country can evaluate the success of

monetary policy in achieving its inflation targets. Mishkin also proposes that

this problem does not arise with either a fixed exchange rate regime or a

monetary aggregate target.

More generally, evidence from different countries has shown

that inflation targeting can be used as a successful approach for gradual

disinflation. Consequently, the Central Banks of many countries now practice

inflation targeting, but allow themselves a little discretion.

2.3.2.5 The Taylor Rule

The Taylor rule is also known as a simple interest rate rule.

That is, simply speaking, it is the current practice where Central Bankers

could formulate policy in terms of interest rates. This rule was originally

proposed by the economist John Taylor following to the need of American Central

Bank to set the interest rates to achieve stable price while avoiding large

fluctuations in output and employment (Mankiw, 2000).

Considering the monetary transmission mechanism as the process

through which monetary policy decisions are transmitted into changes in real

GDP and inflation, Taylor (1995) argued that most Central Banks today are

taking actions in the monetary market to guide the short-term interest rate in

a particular way. In other words, rather than changing the money supply by a

given amount and then letting the short-term interest rate take a course

implied by money demand, the Central Banks adjust the supply of high-powered

money in order to give certain desired movements to the fund rate. The aim is

knowing how much the Central Bank should adjust the short-term interest rate in

response to various factors in the economy including real GDP and inflation.

Taylor proposed a simple interest rule in which the funds rate reacts to two

variables: the deviation of inflation from a target rate of inflation, and the

percentage deviation for real GDP from potential GDP.

Specifically, the Taylor rule can be written as follows:

Rt = r + Ðt + ë1

(Ðt - Ðt*) + ë2

(Yt - Yt*)

Based on the US context in which this rule was conceived, the

symbols in the equation are as follows:

Rt is the nominal federal funds rate, r is the

average equilibrium real federal funds rate, Ðt is the current

rate of inflation, (Ðt - Ðt*) is the

current rate of inflation less the inflation target,

(Yt - Yt*) is the output gap

specified as the excess of actual output over potential output. The

responsiveness of the nominal federal funds rate to the deviation of inflation

from target, and the output gap is determined by the weights ë1

and ë2. The way this rule works can be understood in simple

terms as follows:

The Taylor principle states that the Central Bank's policy

interest rate should be increased more than one for one with increases in the

inflation rate. The Taylor principle ensures that an increase in the inflation

rate produces a policy reaction that increases the real rate of interest. The

rise in the real interest reduces private spending, slows the economy down, and

brings inflation back to the Central Bank's inflation target. Conversely, if

inflation falls below the Central Bank's target, the Taylor principle calls for

a more than one for one cut in the Central Bank's policy interest rate. This

reduces the real rate of interest, stimulates private spending, and pushes

inflation back to its target level (Walsh, 2001).

Over several years there has been an emerging consensus among

economist authors that the Taylor rule appears to be a good description of the

interest rate policies of many Central Banks. Thus, Taylor's rule is the most

popular approach to the empirical analysis of reaction functions (Sanchez-Fung,

2000).

Mankiw (2000) shows that Taylor's rule for monetary policy is

not only simple and reasonable, but it also resembles the American Central Bank

behavior in recent years fairly accurately.

In the light of the different policy rules mentioned above, it

is worth noting that studies on monetary policy rules show that it is possible

to use very simple rules to achieve better economic performance. However,

generally speaking, the question of determining the best rule needs first of

all a better understanding of the transmission mechanism of monetary policy

through the economic system.

CHAPTER 3: MONETARY POLICY IN RWANDA

3.1 Macroeconomic Background

The destruction of the economic basis that took place during

the civil war period (1990-1994) and the genocide (1994) in Rwanda left an

economy in a shambles and characterized among others factors by:

- A very high rate of inflation (64% in 1994) that eroded real

incomes and damaged economic growth,

- A lack of financial control in government ministries leading

to large deficits,

- A narrow export base which concentrated on coffee and

tea,

- Dilapidated infrastructures due to the war and the looting

of saving banks. The institutional structure of the country was in latters.

Overall, the GDP had fallen between 1990 and 1994 by almost a

half.

In response to these challenges, the government embarked along

an ambition path of economic reform which started at the end of 1994. Rwanda

made the transition from responding to emergencies to ensuring sustainable

development. The major objectives of the transition program have been focused

on laying the foundations of the transformation of the economy based on a

process of economic liberalization and turning away from control regulation and

state command to market policies. In the first phase, from 1995 to 1997,

macroeconomic policy reforms concentrated on reviving economic activity,

restoring macroeconomic stability and rebuilding the capacity for macroeconomic

and budget management.

The implementation of the economic reform programs benefited

from the help of IMF and World Bank. The key areas of reforms were in the trade

and exchange regimes, the fiscal area, the financial sector, and the

privatisation. The main emphasis of the policy package adopted was placed on

liberalizing the trade and payment regime. External tariffs were reduced,

exchange regulations were streamlined and further liberalized in 1998, and the

convertibility of the Rwanda francs for current account transactions were also

made in 1998. In the financial sector, in addition to liberalizing interest

rates, and the adoption of a Central Bank law that gave the National Bank of

Rwanda independence in monetary policy in 1997, a new commercial banking law

that provides for effective prudential regulation of commercial banks was

adopted in 1999.

The country began the process of recovery in earnest in 1995.

In 1995 growth in real GDP was 35.2%, in 1996, 12.7%; 1997, 13.8%; 1998, 9%;

1999, 7.6%; 2000, 6%; 2001, 6.8%; 2002, 9.9% (Republic of Rwanda, 2000)

However, it is important to emphasis that the international

community also played a significant role in that success. Indeed, Rwanda has

benefited from IMF and the World Bank sponsored Highly Indebted Poor Countries

(HIPC) debt relief initiatives to tune of US $ 850 million which is about US $

640 million in Net Present Value (NPV) terms. The principal government

objective is controlling inflation. This is being done through measures such

as:

- Improvement in monitoring and control of budget

expenditure,

- Improvement in government saving by enhancing revenue

performance,

- Liberalization of interest rates. Monetary management has

shifted from direct controls to indirect monetary management through open

market operations,

- Reform in tax policy, and the creation in 1997 of the Rwanda

Revenue Authority (RRA). The government took measures to improve the fiscal

situation mostly through improved tax and customs administration and tax

reforms.

These measures were intended to address the traditional

sources of monetary instability in Rwanda, such as monetization of the fiscal

deficit and excessive borrowing from the commercial banks with a view to

strengthening the conduct of monetary policy and the process of financial

intermediation.

Many changes have been noticed in Rwanda from 1995. The

improvements reflect a commitment by the country to sound macroeconomics

policies and more open and better managed economies to address the many social

challenges that exist in the country. The success of such policies have often

been realised with the help of international community in the context of

Medium-Term Policy Programs supported by the IMF and World Bank. Between 1987

and 1999 this help was provided for African countries through the Fund's

Enhanced Structural Adjustment Facility (ESAF). But in late 1999, the ESAF was

transformed into the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PGRF), signifying a

new approach to policy programs and poverty reduction. The issue, therefore, is

for Rwanda's Central Bank to design an appropriate framework that can

accommodate high economic performance in terms of GDP growth and price

stability while contributing to the poverty reduction in the country.

3.2 Monetary and Exchange Rate Policy Management

3.2.1 Monetary Policy

Since the Central Bank of Rwanda assumed its primary

responsibility of formulation and implementation of monetary policy following

the Central bank law that gave the National Bank of Rwanda independence in

monetary policy, several instruments of monetary policy have been actively

applied to regulate liquidity in the economy. The monetary programming has

helped to guide the National Bank of Rwanda's conduct of its monetary policy to

ensure that liquidity expansion is consistent with target inflation and GDP

growth levels.

Monetary programming as a tool of the Central Bank of Rwanda

is characterized especially by the way it describes the monetary by an indirect

character. The objectives that have been set to conduct monetary policy are the

following:

- Final objective: control of inflation,

- Intermediate objective: monetary stock aggregate (M2)

because of the strong correlation between inflation and monetary stock,

- Operational objective: monetary base.

The frame of Central Bank's interventions in the indirect

character of monetary policy consists of:

- Projection of annual monetary balance,

- Forecast to be done on a monthly, quarterly and annual

basis,

- Weekly appreciation of the total level of the banking

liquidity by reference at the desired level of the monetary base.

The monetary instruments that have been used to conduct

monetary are among others:

- Monetary market, which was created in August 1997 as a

single framework for the allowance of the Central Bank currency and the

formation of interest rates through the levels of demand and supply. This

implies the interbank market interventions of Central Bank etc.

- Treasury bills market for monetary policy purposes or for

the needs of the government,

- Obligatory reserves as an instrument of banking liquidity

adjustment.

When the objectives and instruments to be used by the National

Bank of Rwanda are determined the next step to be specified in monetary

programming was focusing on the sources of the creation of currency or

counterparts of the money supply. The latter, as taken by the National Bank of

Rwanda, consists of Net External Assets (NEA) and Net Interior Assets (NIA)

(among others net credit to the private sector). Thus M2 can be expressed

as:

M2 = NEA + NIA

According to the above relation, the change of M2 will consist

of the change of the counterparts (predominance of NEA or NIA). On the other

hand, the regulation of the monetary base follows the counterparts of the

monetary base, which are mainly Central Bank Net External Assets and Central

Bank Net Interior Assets.

The policy of stabilization and economic reforms after the war

period aimed at the re-establishment of fundamental balances. In 1997, as in

previous years, the Central Bank of Rwanda with the Ministry of Economy and

Finance defined an annual inflation target of 7% by the end of 1997. During

1998 and 2000 the inflation was set at below 5%. However, after the

modifications made to the economic program under PRGF (from 1999 to the

present) inflation has been set at 3%. In addition, the GDP growth rate has

been set at 12.7% in 1997; 7% in 1998 and at 6% in 1999 to 2003 in the context

of PRGF.

The macroeconomic objectives undertaken during those years

were oriented towards restoring fundamental economic balances in order to allow

sustainable development. During that period, inflation came down from 11.7% in

1997 to -2.42% in 1999. Nevertheless, as shown in figure3-1, due to the great

inflationary uncertainty associated with the fact that the prices of food

products in Rwanda are often unstable due to the change of climatic conditions

(the drought in some areas) the annual targets for 1997 and 1998 were not

reached. However in 1999 and 2002 inflation was below the proposed target.

TABLE 3-1: INFLATION OBJECTIVE AND INFLATION OBSERVED IN

PERCENTAGE

|

Years

|

Inflation Objective (%)

|

Observed Inflation (%)

|

|

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

|

7

5

3

3

3

3

|

12.1

6.22

-2.42

3.91

3.36

1.98

|

(Source: IMF and Rwanda, 1995-2002)

The monetary programme in Rwanda follows the change in

monetary stock (M2) as an indicator of inflation. The relationship between the

growth of the aggregate M2 and inflation in 1997-2003 periods can be shown in

the figure 3.1 below:

FIGURE 3-1: ANNUAL GROWTH OF AGGREGATE M2 AND INFLATION:

1997-2002

Table 3-2 shows the change in inflation and monetary stock. It

can be seen that the change in M2 depends on how is the predominance in the

change for NEA or NIA.

TABLE 3-2: MONETARY STOCK (M2), NET EXTERNAL ASSET (NEA) AND

NET INTERIOR ASSET (NIA) IN PERCENTAGE

|

Years

|

Monetary stock (M2)

|

Net External Asset

|

Net Interior Asset

|

|

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

|

47.5

-3.9

6.6

14.4

10.1

|

22.6

4.55

-7.05

49.33

21.076

|

77.14

-10.93

20.32

12.207

12.207

|

(Source: Banque Nationale du Rwanda, 2002)

3.2.2 Exchange Rate Policy

The main objectives of Rwanda's exchange rate policy are to

preserve the external value of the national currency and also to ensure the

effective operation of the foreign exchange market. The instruments that are

often used to conduct exchange rate policy are the rate of exchange and

exchange regulations. The latter comprises all the arrangements resulting from

the legislative texts and lawfully taken by the government in order to

supervise the management of foreign currencies.

The flexible exchange rate regime was established in Rwanda in

1995 and at the same time the organisation and the management of the foreign

exchange market were entrusted to the Central Bank.

The characteristic of the Rwanda flexible exchange rate regime

is the fact that it is a controlled flexible policy. The mentioned policy

pursues three main goals:

- To approach as much as possible the balance level of the

rate of exchange,

- The price stability and the support for the growth,

- To connect the Rwandan foreign exchange market to the

international markets.

The instruments of the controlled flexible exchange regime in

Rwanda are simply the rate of exchange reference and the interventions of the

Central Bank on the foreign exchange market. The intervention of the Central

Bank on the foreign exchange market conforms to the pattern of its mission of

ensuring monetary stability and carrying out its objectives regarding the rate

of exchange. This is done with the aim of correcting imbalances of liquidities

of the market, as well as correcting the erratic movements of the national

currency.

In other respects, there is a close link between the monetary

policy and the exchange rate policy. Indeed, one of the principal counterparts

of the money supply, which is the Net External Assets constitute an important

source of monetary creation. According to this view, any positive balance of

the balance of payments results in an increase in the money supply, while any

deficit results in a reduction of the money supply. As a result, since the two

policies aim either at the preservation of the internal value of the currency,

or at its external value, their action must be harmonized for the stability of

the currency.

With the help of international institutions such as the IMF

and the World Bank, the Central Bank of Rwanda is trying to follow an

objective, which entails developing a careful monetary policy, which will allow

it to maintain harmony between the pace of the money creation and that of

economic growth. The management of its stock change has contributed to reducing

the exerted pression on the Rwanda currency and foreign payments. The harmony

that has characterized the growth of the money supply and that of production

has contributed to stabilize the inflation rate, the currency exchange offer

has increased by 9% while it was 13.7% in 2000 (Republic of Rwanda, 2002:

10).

CHAPTER 4 ILLUSTRATION OF THE MONETARY STRATEGY BY

MEANS OF A MODEL

Through economic research, various models have been developed

to better understand the monetary policy impact on the real economy and

ultimately inflation. `The management of monetary policy consists to define the

level of the instrument that, given the transmission mechanism of monetary

policy, is consistent with the achievement of the target' (Martinez, Sanchez

and Werner, 2000: 184). In the context of the conduct of monetary policy in

several countries, the achievement of inflation target has become the

fundamental goal of the monetary authority.

One way to evaluate the effectiveness of the monetary policy

is by estimating the effect on the interest rate of the variables that should

enter into the authorities reaction function. The Taylor rule mentioned

previously is one of the more popular approaches to the empirical analysis of

the reaction function. Indeed this rule works with the interest rate policy and

the latter implies the open market operations, which are often taken as the

most important monetary policy tool because they influence short-term interest

rates and the volume of money and credit in the economy.

The monetary reaction function based on the Taylor rule has

been used in both developed and underdeveloped countries. Judd and Rudebush

(1998) quoted in Hsing, (2004) investigated and reviewed previous works and

maintained that the Taylor rule is a valuable guide to characterize major

relationships among variables in conducting monetary policy. Similarly, Romer

(2001) quoted again in Hsing, (2004) analysed several issues in applying the

Taylor rule. He noted that the values for the coefficients of the output gap

and the inflation gap would change the effectiveness of monetary policy. Larger

values of the coefficients would cause the actual inflation rate and output to

decline more than expected. Due to a lag in information, it would be more

appropriate to use the lagged values for the output gap and the inflation gap.

The exchange rate and the lagged federal funds rate need to be included to

incorporate the open economy and the partial adjustment process. Martinez,

Sanchez and Werner (2000) analysed the mechanisms empirically by which the

transmission of monetary policy has occurred in the Mexican economy from 1997

to 2000. Using VARS he found that the behavior of the real interest rate was

determined by the traditional variables that guide the discretionary actions of

any Central Bank and that this rate affected aggregate demand and credit in a

statistically significant way. Applying the VAR model, Hsing (2004) estimated

the monetary policy reaction function for the Bank of Canada. The results show

that the overnight rate has a positive and significant response to a shock in

the output gap, the inflation gap, the exchange rate or the lagged overnight

rate. The author pursues the latter concluding that the main outcomes suggest

that in pursuing monetary policy by the Bank of Canada, targeting output is as

important as targeting inflation.

Sanchez-Fung (2000) estimated a simple Taylor-type monetary

reaction function for Dominican Republic during the period 1970-98. He noted

that the implicit reaction of such authorities suggest that they were more

systematic during the period 1985-98 which might be attributed to a

determination to» implicitly» follow feedback rules, rather than

discretion, in monetary policy-making. Setlhare (2003) studying how monetary

policy was conducted in Botswana by specifying and estimating an empirical

monetary policy reaction for the Bank of Botswana over the period 1977-2000,

identified a predominantly countercyclical policy reaction function. This

reaction function suggests that inflation (directly and indirectly via the real

exchange rate) is the ultimate variable of policy interest.

Smal and Jagger (2001) examined the monetary transmission

mechanism in South Africa. The results of the model developed indicated that

there was a fairly long time (one year) before a change in monetary policy

affected the level of real economic activity, and another year before it had an

effect on the domestic price level.

Sanchez-Fung (2000) however, observed that although the

framework related to Taylor type monetary policy reaction has been implemented

in the analysis of advanced economies, little work has been done for less

developed countries.

The purpose of the following section will look at how monetary

policy was conducted in Rwanda by specifying and estimating a monetary reaction

function for National Bank of Rwanda.

4.1 EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

4.1.1 Reaction function for Rwanda

Rwanda is a small open economy and it is necessary to examine

how monetary policy reacts to output gap, inflation gap and exchange rate.

To formulate a monetary reaction function for National Bank of

Rwanda the Taylor rule equation was adapted to the context of monetary policy

in Rwanda. Indeed, Osterholm (2003) showed that the Taylor rule could be

estimated where the rule has been used by Central Banks or at least be a close

enough approximation to Central Bank behavior.

The original Taylor rule can be expressed as following:

FFR=f (YG, IG) (1)

Where

FFR= the federal funds rate,

YG= the output gap,

IG= the inflation gap which is (-*), where is the

actual inflation rate and * the target inflation rate.

The present study will follow suit by specifying and

estimating a version of (1). That is, will be determined a variable that seems

to be a plausible indicator of the stance of monetary policy in Rwanda.

Evidence suggests that the short-term interest rate cannot be applied to the

realities of developing countries when taken as an instrument in conducting

monetary policy given the underdeveloped nature of the financial market. It has

been argued that the monetary base is the most appropriate instrument to be

used in developing countries (Sanchez-Fung, 2000).

Because of data availability problems for the monetary base

series of Rwanda, the monetary stock aggregate (M1) will be used as the

instrument policy. Indeed, the monetary stock aggregate (M1) plays an important

role in Rwanda monetary policy since the National Bank of Rwanda assumed its

responsibility to regulate liquidity in the economy and the data of the

monetary base are frequently referred to M1.

In respect of goal variables, inflation and output will be

used. The former variable has emerged from many economists as the real goal of

monetary policy in order to maintain price stability and the latter is

considered as a historically objective of monetary policy in various

countries.

In the context of Rwanda, the strategy used by the Central

Bank is to ensure that liquidity expansion is consistent with target inflation

and GDP growth levels. Thus, the modified version of Taylor's rule to be

estimated can be written as:

Mt= ë0 + ë1 (IGt) +

ë2 (YGt) + t (2)

However, recently, with number of empirical studies related to

the Taylor rule, economists argue that the exchange rate would also be an

essential state variable that has to be included in the model in the case of a

small and open economy (Osterholm, 2003). On this basis, the equation (2) is

extended as follow:

Mt= ë0 + ë1 (IGt) +

ë2 (YGt) + ë3DEXt +

t (3)

Where Mt = monetary stock aggregate (M1),

DEXt = the change in exchange rate in

terms of the Rwandan Francs per US

Dollars,

t = the error term and

ë0, ë1,

ë2, ë3 are constant term and coefficients

respectively to be estimated empirically.

The equation (3) can be seen as a function in which the

monetary stock aggregate (M1) reacts to the inflation gap, output gap and the

change in exchange rate.

The version of the equation (3) to be empirically estimated

can take a dynamic form since there is the lag response of Monetary Authority.

On this basis, the equation (3) is expressed as follows:

Mt= 0 + 1Mt-1 +

2IGt + 3IGt-1 +

4YGt + 5YGt-1 +

6DEXt + 7DEXt-1 + t

(4)

Equation (4) is an autoregressive-distributed lag of order one

[ADL (1, 1)]. This formulation allows one to consider that the forecast value

of M at time t is simply the reaction of monetary authorities to

past and current economic states. Moreover, following Sanchez-Fung (2000: 9)

one should consider that, statistically; equation (4) could help to justify the

problem of wrongly measured data.

4.1.2 Methodology

4.1.2.1 Data

The econometric analysis of the version of Taylor rule

retained for Rwanda will be undertaken using quarterly data during 1997 (Q1) -

2001(Q4), simply because the monetary authorities actually began to carry out

monetary policy in an independent way from 1997. However, data for the

variables after 2001(Q4) are not available.

Real GDP, Index of Consumer Prices, monetary stock aggregate

and nominal exchange were obtained from the Central Bank of Rwanda and have

been all transformed in logarithm form, except the Index of Consumer Price. In

addition, the inflation rate is calculated as the change over four quarters of

the seasonally adjusted harmonised Index of Consumer Prices and the inflation

gap has been taken as the difference between the observed inflation and the

inflation target. The Inflation target is not constant and was obtained from

IMF and Rwanda (1995-2002) and the National Bank of Rwanda. Potential output is

estimated based on the Hodrick-Prescott Filtering Process and the output gap is

expressed as (Y-Y*), where Y is the output and Y* is the

potential output. The monetary stock aggregate variable has been de-trended

using the HP filter (see Pesaran and Pesaran, 1997). The nominal exchange rate

reported is in terms of Rwandan Francs per US Dollar because of the extensive

use of US Dollars to dominate international transactions (Republic of Rwanda,

2000: 369).

By using this data, the focus will be on estimating the model

(4) using Microfit 4.0 and by checking whether the estimated parameters of the

regression are meaningful to interpretation.

4.1.2.2 Time series properties of the data

Prior to carrying out the model, it is necessary to examine

the time series properties of the variables included in it. This allows one to

determine whether or not the regression is spurious. For this purpose

stationarity of the data set is checked by using a simple appropriate test

named Dickey- Fuller. The lag length used in the test is determined using the

AKAIKE (AIC) and the Schwartz Bayesian Criterion (SBC) mainly. According to

this criterion, the model to be preferred should have the highest AKAIK or the

highest SBC.

Tables (4.1) and (4.2) present the integration test results

for variables in their level form and in first difference respectively.

TABLE (4.1): UNIT ROOT TEST-LEVELS OF VARIABLES

|

Variables

|

Trend

|

Constant

|

ADF (t)

|

Lag

|

|

Monetary stock aggregate (M)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

-3.8241**

|

2

|

|

Inflation gap (IG)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

-4.1838**

|

1

|

|

Output gap (YG)

|

No

|

No

|

-5.1630**

|

4

|

|

Exchange rate (EX)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

-1.5882

|

2

|

Note: ADF critical values:

* Significant at the 1% level

** Significant at the 5% level

TABLE (4.2): UNIT ROOT TESTS OF THE FIRST DIFFERENCE

|

Variables

|

Trend

|

Constant

|

ADF (t)

|

Lag

|

|

DM

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

-9.0445*

|

0

|

|

DIG

|

No

|

No

|

-3.7920**

|

0

|

|

DYG

|

No

|

No

|

-3.7141*

|

0

|

|

DEX

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

-16.3773*

|

0

|

Note: ADF critical values:

* Significant at the 1% level

** Significant at the 5% level

The results reported in Table (4.1) indicate that all the