KIGALI INDEPENDENT UNIVERSITY (ULK)

SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS STUDIES

DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS

POBox: 2288 KIGALI-RWANDA

AFFECTING AGGREGATE CONSUMPTION

EXPENDITURE IN RWANDA

PERIOD: 1995-2015

WELFARE

DETERMINANTS

A research thesis submitted in the partial fulfillment of the

requirements of the award of bachelor's degree in economics

Submitted by: -NIZEYIMANA Alphonse: 31075

SUPERVISOR: Prof. Dr. RUFUS Jeyakumar

Kigali, September, 2016

III

DECLARATION

I, NIZEYIMANA Alphonse hereby declare that this dissertation

entitled «Welfare implication of determinants affecting aggregate

consumption expenditure in Rwanda: 1995-2015» is my own work and

it has not been submitted anywhere for the award of any degree.

NIZEYIMANA Alphonse

Tel: +250788851921/+250787077701

Email:

nzmnalphonse@gmail.com

iv

APPROVAL

This is to certify that this dissertation work entitled

«Welfare implication of determinants affecting aggregate

consumption expenditure in Rwanda 1995-2015» is original research

conducted by Mr. NIZEYIMANA Alphonse under my supervision and

Guidance as a University full lecturer.

Supervisor: Prof. Dr. RUFUS Jeyakumar

Full Professor and Dean of the School of Economics and Business

Studies at Kigali Independent University (ULK)

Email: deanfebskigali@ulk.ac.rw

Tel: +250788303668/+250788620205

To my brothers, sisters,

friends and beloved

relatives

To my parents with my

whole family for their

endless

affection,

DEDICATION

V

AKNOWLEDGMENT

I would like first to acknowledge and thank God for loving and

blessing me since my birth until now.

I thank particularly Prof. Dr. RUFUS Jeyakumar

who devoted part of his time to the supervision of this work. His

invaluable guidance contributed to the successful completion of this

research.

I would like to expand my thanks to my beloved HABIMANA

Canisius's whole family.

I would like to expand my thanks to brothers and best friends:

Mr. NSABIMANA Amiable, Mr. HATEGEKIMANA Jean Baptiste,

Mr. HAREMIMANA Joseph, Mr. NGIRIMANA Benjamin and their

families who more contributed to the achievement of this work.

Thanks go to my beloved family Mme

NYIRAMBARUSHIMANA Alexandrine and my first bone BUSINGYE Thea

Isabelle who all encouraged me during my studies. Thanks go to my

friends, colleagues and classmates precisely in the department of economics for

making my student life enjoyable.

vi

May God bless them!

VII

LIST OF ACCRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

%: Percentage

AD: Aggregate Demand

ADF: Augmented Dickey-Fuller

APC: Average Propensity to Consume

APC: Average Propensity to Consume

AS: Aggregate Supply

BNR: Bank National du Rwanda

Co: Autonomous Consumption

CPI: Consumer Price Index

DHS: Demographic Health Survey

?: Change (increase or decrease)

e: nominal exchange rate

EXCHR: Exchange rate

Frw: Rwandan Francs

GCE: Gross Consumption Expenditures

GDP: Gross Domestic Product

GNP: Gross National Product

i.e.: It means

INF: Inflation rate

INT: interest rate

LDC: Less Developed Country

LM: Lagrange Multiplier

MPC: Marginal Propensity to Consume

NDP: Net Domestic Product

VIII

NNP: Net National Product

OLS: Ordinary Least square

PCE: Personal consumption expenditures

PP: Philip-Peron Calculated value

R2: R-square

SACCOs: Savings and Credit Cooperative

Organizations

U L K: Kigali independent university

WWW: World Wide Web

X-M: Export minus Import

Yd: Disposable income

å: Real exchange rate

ix

ABSTRACT:

The research on welfare implication of determinants affecting

aggregate consumption expenditure was conducted by taking Rwanda as an area of

study, period 1995- 2015. The researcher's main purpose was to evaluate the

impact of gross domestic product, lending interest rate, inflation rate and

exchange rate on consumption expenditure in economy. To achieve the desired

objectives, the researcher analyzed how independent variables of the Gross

consumption expenditure (GDP, Lending Interest rate, Inflation rate and

Exchange Rate) work and how they affect the dependent variable (GCE). Augmented

Dickey-Fuller (ADF) and Phillips- Peron (PP) tests were used for stationarity

test. Engle- Granger two steps procedure and the Johansen Maximum Likelihood

Methodology were used to see whether variables are co-integrated or not. The

series analysis was done using Eviews 8 Software. Those tests revealed that

there is co-integration among variables. The researcher found that the economic

authorities in Rwanda use different tools of monetary policy and fiscal policy

in order to stabilize the economy, using determinants such as: money supply,

government spending, credit control, interest rates and other monetary and

fiscal measures can be manipulated by the economic authorities of Rwanda to

maintain welfare of the society.

Keywords:

Gross consumption expenditure(GCE), Inflation rate

measured by Consumer Price Indices(CPI), Exchange rate, Lending interest rate,

, Gross domestic product(GDP).

X

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Status and trends of gross

consumption expenditure, Gross domestic product, Interest rate 29

Table 2: Stationarity at Level 39

Table 3: Stationarity at first difference

40

Table 4: Stationarity at second difference

41

Table 5: Long run Johansen Co-integration

test output 55

Table 6: Long run output effect of changes in

GDP, INT, INF, and EXCHR on Gross 56

Table 7: Short run relationship effect of

changes in GDP, INT, INF, and EXCHR on Gross 57

Table 8: Serial correlation tests 60

Table 9: Heteroscedasticity Test 60

Table 10: Ramsey reset Test 61

xi

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: Inflation Keynesian View 23

Figure 2: Status and trends of gross

consumption expenditure, Gross domestic product, Interest rate 30

Figure 3: Jarque-bera Test output 59

Figure 4: Cusum test 62

XII

TABLE OF CONTENTS

APPROVAL iv

LIST OF TABLES x

LIST OF FIGURES xi

GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1

1.Background of the study 1

2.Significance of the study 2

3.Scope and period of the study 3

4.Problem statement 3

5.Hypothesis 5

6.Objectives of the study 6

6.1General objectives 6

6.2Specific objectives 6

7.Research methodology 6

7.1Techniques 6

7.1.a. Documentary technique 7

7.1.b. Interview technique 7

7.2 Methods 7

7.2.a. Statistical method 7

7.2.b. Analytical method 7

7.2.c Historical method 8

7.2.d Comparative method 8

7.2.e. Econometric method 8

8. Organization of the study 8

CHAP I: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 9

INTRODUCTION 9

Definition of the key concepts 9

1.1 Welfare: 9

1.1.a. The Genesis of the Welfare State 9

1.2 Consumption 10

1.2. a. Autonomous consumption 11

XIII

1.2. b. Marginal propensity to consume 11

1.2. c Disposable income 12

1.3 National income 13

1.3.a. Definitions of National Income: 13

1.3.b Concepts of National Income: 16

1.4 Interest rate 19

1.4. a. Nominal Interest Rate 19

1.4.b Real Interest Rate 20

1.4. c Effective interest rate 20

1.5. Inflation rate 20

1.5.1. Causes of inflation 21

1.5.1.a. The cost push-inflation (On the supply side) 21

1.5.1. b Demand-Pull Inflation (On the demand side) 22

1.5.2 Keynesian inflation theory 23

1.6. Exchange rates 24

1.6. a. Nominal exchange rate (e) 24

1.6.b. Real exchange rate (å) 24

CHAPTER 2 ANALYSIS OF THE STATUS AND TRENDS OF

DETERMINANTS 27

INTRODUCTION 27

2.1. Evolution of gross consumption expenditure in Rwanda

1995-2015 27

CHAPTER 3 ECONOMETRIC ANALYSIS OF THE RELATIONSHIP OF

35

INTRODUCTION 35

3.1 Model specification 35

3.1.1 Hypothesis of the model 36

3.1.2. Expected signs 37

3.1.3 Test and analysis of the data 37

3.2. Data processing 37

3.2.1. Unit root tests 37

3.2.1.a. Why testing stationarity? 37

3.2.1.b. Interpretation of stationarity test 53

3.3 Estimation of long run model 53

xiv

3.3.1 Co-integration test 53

3.3.2 Interpretation of Johansen Co-integration test output

55

3.3.3 Long run output 56

3.4 DIAGNOSTIC TESTS 58

3.4.1 Jarque-bera test (Normality test) 59

3.4.2 Breusch-Godfrey test (Serial correlation LM test)

60

3.4.3 Heteroscedasticity Test (Breusch Pagan Godfrey) 60

3.5 STABILITY TESTS 61

3.5.1 Ramsey reset test 61

3.5.2 Recursive estimates (OLS only): Cusum test 61

CONCLUSION ..64

SUGGESTIONS 64

REFERENCES ..66

APPENDICES 68

APPENDICES I 69

APPENDICES II 71

1

GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1.Background of the

study

In Rwandan economy as other economic systems of different

countries, among several key macroeconomic variables that determine aggregate

output, aggregate consumption appears to be an output determining variable that

has attracted a lot of attentions and studies. As one of the fundamental

components of gross national product (GNP) & gross domestic product (GDP)

and a major variable for measuring economic growth, consumption expenditure and

the nature of the consumption function have engaged much of the macroeconomic

debate dating back to John Stuart Mills and the classical economists of the

18th & 19th centuries, J.M. Keynes, Milton Friedman,

Franco Modigliani, James Duesenberry, Simon Kuznet etc. in the early to

mid-19th century.

This is so because consumption expenditure accounts for about

2/3of aggregate expenditure in virtually all economies. Consumption

according to (Blanchard O. 2003) is the act of using goods and services for the

purpose of satisfying man's innumerable needs. This encompasses the importance

of consumption in welfare. The aggregate consumption expenditure level which

includes expenditure on durable and nondurable goods shows the general position

of an economy. Neoclassical economists generally consider consumption to be the

final purpose of economic activity and thus, the level of consumption per

person is viewed as a central measure of an economic productive success. The

study of consumption behavior plays a central role in both macroeconomics and

microeconomics. Macroeconomists are interested in aggregate consumption for two

reasons. First aggregate consumption determines aggregate saving because

aggregate saving defined as the portion of income not consumed, flows through

the financial system to create the national supply of capital.

It follows that the aggregate consumption and saving behavior

have a powerful influence on economy's long term productive capacity. Second,

since consumption expenditure accounts for most of national output,

understanding the dynamic of aggregate consumption expenditure is essential to

understanding macroeconomic fluctuation and the business cycle. Microeconomists

have studied consumption behavior for many reasons such as using consumption

data to measure poverty, to examine the household's preparedness for retirement

or to test theories of competition in retail industries. A rich variety of

household level data sources in Rwanda allowed the researcher in this work to

examine household spending behavior, which has also been utilized to examine

interactions between

2

consumption and other economic behaviors such as job seeking

or educational attainment in Rwanda. From the foregoing, it is important to

point out that both the government of Rwanda and household sectors of the

economy engage in consumption expenditure. The determinants of consumption

expenditure have been influenced by a number of other economic variables. To

study factors both quantitative and qualitative such as income, wealth,

interest rate, capital gain, liquid assets, etc. that can influence

consumption, as whatever influences consumption expenditure, plays a major role

in the process of economic growth in every economy and that of Rwanda as well.

Consumption decision and behavior is crucial for both short run and long run

analysis because of its role in determining aggregate output.

2.Significance of the study

The general interest of this study is to conduct a research

and the report can help understand the content of welfare implication of

determinants affecting aggregate consumption expenditure in Rwanda. It is very

important to understand household consumption and its determinants because

consumption and saving behavior have a powerful influence on economy's long

term productive capacity. It can help the society of Rwanda to know the effects

and the level of consumption expenditure so that they can manipulate it.

To the researcher

This study helped the researcher to be more acquaint with the

important role of income, interest rate, inflation rate as well as exchange

rate in influencing consumption decision. This can help also to know that as

increase in income encourages consumption as well as savings. As Rwandan who

has observed different problem in our society, a researcher has been interested

to undertake this work.

To Rwanda community

It can help the community to know how to behave in daily life;

therefore it helps to know how the income determines the level of consumption.

It helps educated people to take seat and introspect to which extent the level

of savings can really be in order to enhance the level of economic growth. This

study viewed as source of documentation to the future researchers and to

students taking similar field.

To ULK

This study also served to the Kigali Independent University

economic Students when they will be choosing their topics to prepare their

dissertations in coming days. The realization of this work complies

3

with the academic requirement by which any student completing

the provided undergraduate program of course has to conduct a research, compile

and present a dissertation in order to be awarded a bachelor's degree.

3.Scope and period of the study

This study is addressing on assessment on welfare implication

of determinants affecting aggregate consumption expenditure in Rwanda. We

normally assessed the level of aggregate consumption as a function of income,

interest rate, inflation rate and exchange rate as well such the Rwanda, after

1994 Genocide, the economy was really in recessionary period so that it was not

easy for the community to produce and consume. The research dated from

15st March 2016 and ended on 15th August, 2016 and then

presented on September 06th, 2016.

4.Problem statement

Rwandan economy is struggling for balance of payment deficit

because of high level of imports and lower level of export, the Rwanda currency

which is depreciating day to day, a continuous increase of prices as well as

the high level of lending interest rate. The level of income is normally lower

because of lower level of return of wages and many other factors. This study,

therefore, aims at finding out the trends of key macroeconomic variables that

determine aggregate consumption expenditure in Rwanda from 1995 to 2015. The

theory underpinning this study stems from the nature and relationship between

consumption and income. The most undeniable attention to what has come to be

called the consumption function was first well thought out by John

Maynard Keynes. In less developed counties (LDC) like Rwanda,

consumption expenditures are based on actual income, not full employment or

equilibrium income, important savings and investment determinants include

income, expectations, and other influence beyond the interest rate. These

assumptions imply that the economy can achieve a short-run equilibrium at less

than full-employment production. According to Keynesian theory, changes in

aggregate demand, whether anticipated or unanticipated have their greatest

short run impact on real output and employment, not on price. Rationalizing

rigid prices is hard to do because according to standard microeconomics theory,

real supplies and demands do not change if all nominal prices rise or fall

proportionally. If government spending increases, for example, all other

components of spending remain constant, then output will increase.

Therefore, J.M Keynes's absolute income hypothesis didn't give

account. Milton Friedman emphasized that consumers smooth their expenditure by

borrowing and

4

lending. He posited that consumption is determined by long

term expected income rather than current level of income. He argued that

consumption in one day is determined not by income received on that day but on

the average daily income received for a period. Income consist of a permanent

(anticipated and planned) component and a transitory (windfall gain/unexpected)

component (Anyanwu, 1993). Milton Friedman noted that permanent income or

expected long average income is earned from both human and non-human wealth

consisting of labor income, saved money, debentures, equity shares, and real

estate and consumer durables goods like cars, refrigerators, air conditioner,

TV sets etc. This theory made an important contribution by laying stress on

changes in interest rate and wealth as well as the desire to add to one's

wealth (Forgha, 2008). Many economists have posited that consumption depends on

a person's lifetime income. Franco Modigliani emphasized that income varies

systematically over people's lives and savings allow consumers to move income

from the time in life when income is high to low income lifetime period in

order to smoothen consumption. The life cycle hypothesis is based on household

utility maximizing behavior defined on present and future consumption subject

to a lifetime resources constraint. It assumes that price is constant, interest

rate is stable and consumers do not inherit any asset and as such the wealth

owned by a consumer are his own. It also indicates that consumption in a period

depends on the total resources (wealth) one has to spend over his remaining

lifetime which composes of initial wealth and expected earnings at late stage

in life. (Onuchuku, 1998).

Keynes in his book «The General Theory of

Employment, Interest rate and Money» published in 1936 laid the

foundation of modern consumption theories. Keynes mentioned several subjective

and objective factors which determine the consumption of a society. However, of

all factors, he posited that the level of income determines the consumption of

an individual and the society. He laid stress on the absolute income of an

individual as the major determinant of consumption and as such, his theory was

regarded as the absolute income hypothesis. His theory centered on the

relationship between the Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC) and

Average Propensity to Consume (APC).

Further, Keynes put forth the fundamental «psychological

law of consumption» according to which he propounded that as income

increases, consumption increases, though not by as much as the increase in

income. In other words, the marginal propensity to consume is less than 1,

means that 0<MPC<1.

Keynes made 3 salient points from his proposition. First,

consumption expenditure depends mainly on absolute income of the current

period. Second, consumption is a positive function of absolute level of current

income and third, the more income derived, the more the consumption expenditure

in that period (Jhingan, 2002).

5

Keynes posited that interest rate does not have an important

role in influencing consumption decision. This stood in stark contrast to the

classical economist who believed that a higher interest rate encourages savings

and discourages consumption (Blare, 1978). Based on conjectures, Keynesian

consumption function is given as C= C0 + bYd, a>0, where C is the

consumption, Yd is disposable income; C0 is consumption when income

is zero (autonomous consumption) and b is the rate of change of consumption due

to change in income called the marginal propensity to consume (MPC). While this

theory has success modeling consumption in the short run, attempt to apply this

model over a long time frame proved less successful. This led to the emergence

of other consumption theories put forth by several economists based on other

key factors which is believed to determine consumption other than income. From

all the reason above the researcher has to conduct this study basing on the

following two questions:

? What is the status and trends of gross consumption

expenditure, income, interest rate, inflation rate and exchange rate from 1995

up to 2015 in Rwanda?

? Is there any relationship between consumption, income,

interest rate, inflation rate and exchange rate from 1995-2015 in Rwanda?

5.Hypothesis

In order to respond to the above mentioned questions in this

statement of the problem, same hypothesis were indicated to guide the

researcher for positive or negative conclusion that can be explained like

anticipation or opinion regarding the result of the study. Another fact is

prediction regarding the possible outcomes from the study in term of the

variable that hypothesis is tentative proposition which is subject verification

through subsequent investigation (CRAWITZ, 2001-198). So the provisionary

answers from the above mentioned questions are the following:

? Trends positions of gross consumption expenditure that is

relative to its associates to which it belongs in Rwanda are upward sloping.

? There is a long run relationship between gross consumption

expenditure and its associates in Rwanda.

6

6.Objectives of the study

This research aims at general and specific objectives and, which

give a sense to the general objective 6.1General objectives

The general objective of this study is to verify the impact of

income, interest rate, inflation rate and exchange rate on gross consumption

expenditure in Rwanda.

6.2Specific objectives

This study pursues the following specifics objectives:

? To identify the relationship between explained and explanatory

variables of the above

mentioned model in Rwanda

? To study and examine the trends of that model.

? To give suggestions to policymakers

7.Research methodology

Research methodology is the general approach which will be

used while conducting the present study. This research methodology refers

systematically to solve the research problem above mentioned. It can be also

defined as analysis of principles of methods rules and postulates employed by a

discipline, and the systematic study of methods that are the main intention of

the research to find out how change can be implemented effectively within an

organization and to suggest some solutions to correct wrong issues (KHOTAR,

2004)

7.1Techniques

In research, techniques are the way used to collect data from

the field. There are many ways of collecting data such as sample size,

questionnaire, documentary, interview and so on. During this work, techniques

that helped the researcher are the following:

7

7.1.a. Documentary technique

This technique is used to collect information from written

sources related to the topic like: Books, Journals, Brochures, Internet,

Reports, archives and so on.

7.1.b. Interview technique

This technique use face to face or telephone by asking

prepared questions to persons from the targeted institutions or groups. These

questions are related to the research that is being undertaken.

7.2 Methods

The method is a set of intellectual operations which enable to

analyze, to understand and to explain the analyzed reality or to structure the

research. To conduct this research, the following methods used:

7.2.a. Statistical method

Statistical method is the application of statistical and

mathematical methods in the field of economics to analyze and describe the

numerical relationship between key economic variables (KHOTAR, 2005). The

results of analysis are tables and figures estimated by a method of ordinary

least squares (OLS), from the parameters of the model that we have

identified.

7.2.b. Analytical method

The analytical method is a generic process combining the power of

the Scientific Method with the use of

formal process to solve any type of problem. It has these nine

steps:

+ Identify the problem to solve.

+ Choose an appropriate process.

+ Use the process to hypothesize analysis or solution

elements.

+ Design an experiment(s) to test the hypothesis.

+ Perform the experiment(s).

+ Accept, reject, or modify the hypothesis.

+ Repeat steps 3, 4, 5, and 6 until the hypothesis is

accepted.

+ Implement the solution.

+ Continuously improve the process as opportunities arise.

8

This method have been used to analyze the data collected,

other information applied to the research and to understanding theoretical

relationship between consumption, income, interest rate, inflation rate and

exchange rate.

7.2.c Historical method

We have used data from recent years and have been able to

interpret them based on historical evidences. Without history and research

materials in the past, this work would not have been able to succeed.

7.2.d Comparative method

In this research, different ways already available to help in

comparing data have been very helpful in analyzing the data in the period under

study.

7.2.e. Econometric method

Econometrics method is the application of mathematics,

statistics and computer science to economic data and is described as the branch

of economic that aims to give empirical content to economic relations.

This method has been used to compute some parameters with E-views

software and have been used in testing the hypotheses in order to determine the

level of significance. Econometrics is the application of mathematical and

statistical methods to economic data and is described as the branch of

economics that aims to give empirical content to economic relations.

8. Organization of the study

This study is composed of the introduction, three chapters and

conclusion. General introduction includes a brief detail of the above mentioned

point from the back ground to the selected methods to be used:

? The first chapter is the literature review

of the key concept, this means all theories related to the topic of

economics.

? The second chapter presents the analysis of

evolution of trends of consumption, income, interest rate, inflation rate and

the exchange rate.

? The third chapter focuses on the

econometric analysis of the impact of income, interest rate, inflation rate and

exchange rate on aggregate consumption expenditure in Rwanda. Finally, there is

conclusion of the work and suggestions to policymakers.

9

CHAP I: REVIEW OF LITERATURE INTRODUCTION

The theoretical framework of this chapter is the theoretical

literatures which explain in deep the different variables of the used model.

The presentation of different researches which was conducted using the same

variables showing the empirical evidences therefore the researcher focused on

the summary of the gaps to fill in the study.

Definition of the key concepts

1.1 Welfare: In this research, a discussion

on welfare occurred to know whether any allocation of resources is efficient or

not. By efficiency in economics a researcher mean whether any state or

situation regarding resource allocation maximizes social welfare. In welfare

economics attempt is made to establish criteria or norms with which to judge or

evaluate alternative economic states and policies from the viewpoint of

efficiency or social welfare. These criteria or norms serve as a basis for

recommending economic policies which will increase social welfare. Thus the

norms established by welfare economics are supposed to guarantee the optimal

allocation of economic resources of the society. Welfare in economics is

defined as a branch of economics that studies how the distribution of income,

resources and goods affects the economic well-being of the community. An

example of welfare economics is the study of how certain health services help

bridge the barrier between different classes of people.

1.1.a. The Genesis of Welfare State

According to Barr 2004, the Welfare State «defies precise

definition». The main reasons are that welfare derives from other sources

besides state activity and there are various modes of delivery of the services

made available to citizens. Some are funded but not produced by the State, some

publicly produced and delivered free of charge, some bought by the private

sector, and some acquired by individuals with the money handed on to them by

the State. Although its boundaries are not well defined, the Welfare State is

used as «shorthand for the state's activities in four broad areas: cash

benefits; health care; education and food, housing, and other welfare

services» (Barr 2004:21). The objectives of the Welfare in economics can

be grouped under four general headings. It should support living standards and

reduce inequality, and in so doing it should avoid costs explosion and deter

behavior conducive to moral hazard and adverse selection. All these objectives

should be achieved minimizing administrative costs and the abuse of power by

those in charge of running it.

10

1.2 Consumption

Consumption is defined as the use of goods and services by

consumer purchasing or in the production of goods. Personal consumption

expenditures (PCE) are measures of price changes in consumer

goods and services. Consumption refers to the expenditures of goods and

services that give satisfaction in the present time. It is the use of resources

to satisfy human needs. Gross consumption expenditure is the use of resources

used to satisfy human needs at current price. Goods that human always use to

satisfy their needs are therefore divided into subcategories.

Durable goods: These are products that are

not quickly consumed and can be conserved along time. These are tangible goods

that tend to last for more than a year. Common examples are cars, furniture,

and appliances. Durable goods constitute about 10-15 percent of consumption

expenditures.

Non-durable goods: These are products that

are consumed immediately which mean they have a short lifespan. These are

tangible goods that tend to last for less than a year. Common examples are

clothing, food, and gasoline. Non-durable goods constitute about 25-30 percent

of consumption expenditures. Services: A type of economic

activity that is intangible not stored and does not result in ownership. A

service is consumed at the point of sale. Services are one of the two key

components of economics, the other being goods. These are intangible activities

that provide direct satisfaction to consumers at the time of purchase. Common

examples include health care, entertainment, and education. Services constitute

about 55-60 percent of consumption expenditures.

This function is used to calculate the amount of total

consumption in the economy. It is made up by autonomous that is not influenced

by current income and induced consumption that is influenced by economy's level

of income. In its most general form, the household's lifetime value function

can be: consumption in `youth' while the second

argument represents consumption in `old age'. Simply,

this function can be written in variety of ways for example, it can be

expressed as C=a+b(Y-T). Again, it can be expressed as C=C0+C1Yd

Where:

C: total consumption

C0: Autonomous consumption

C1: Marginal propensity to consume

Yd: Disposable income (This is the income after

Government taxes and transfer payment)

11

1.2. a. Autonomous consumption

Autonomous consumption also known as exogenous consumption is

defined as expenditures taking place when disposable income levels are at zero.

This consumption is typically used to fund consumer necessities, but causes

consumers to borrow money or withdraw from savings accounts. It is the

consumption expenditure that occurs when income levels are zero. Such

consumption is considered autonomous of income only when expenditure on these

consumables does not vary with changes in income; generally, it may be required

to fund necessities and debt obligations. In the above mentioned function, the

autonomous consumption is shown by C0.

1.2. b. Marginal propensity to consume

In economics, the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is a

metric that quantifies induced consumption, the concept that the increase in

personal consumer spending (consumption) occurs with an increase in disposable

income (income after taxes and transfers); therefore it is the slope of

consumption function. Because this metric is assumed to be positive, thus a

positive relationship between consumption and income occurs and if income

increases, the level of consumption increases too. However, Keynes mentioned

that the increase of income and consumption is not equal. The Keynesian

consumption function is also known as the absolute income hypothesis as it is

only based on current income and ignores potential future income.

Criticisms of this consumption led to the development of

Milton Friedman's permanent income hypothesis ad Franco Modigliani' lifecycle

hypothesis. The marginal propensity to consume (MPC) cannot be calculated

without disposable income. In the classic Keynesian framework, disposable

income is the income left over after taxes and is divided between consumption

and investment. Suppose that an individual receives an extra 2000 0 Frw and

spends 18000Frw, saving the remaining 2000 Frw. His MPC is 0.9, or

18000/20000.

The effect is said to be marginal because it assumes new

income being introduced to a previously static state. The marginal propensity

to consume was presented in John Maynard Keynes' work "The General Theory of

Employment, Interest, and Money." Keynes titled this work to evoke comparisons

between his general theory of economics and Albert Einstein's theory of general

relativity. Keynes believed his work was as seminal to mathematical economics

as Einstein's was to mathematical physics. MPC was the starting point to

Keynes' central mathematical arguments. Keynes noted that individual

consumption is divided between consumption and investment. He expressed this

argument as Y = C + I. He further

12

stipulated that any marginal increase in income would be

divided between consumption and investment, or OY = OC + OI. Keynes then

extrapolated from this that communities would have a general tendency to spend

a fraction of its new income. He shows this with OC/OY, or marginal consumption

divided by marginal income. The only thing left over from his formula,

investment, would receive the rest. Later on in "The General Theory of

Employment, Interest, and Money," Keynes manipulated the relationship between

income, consumption and investment to justify his multiplier. Later Keynesians

have argued that this multiplier effect is greater for poorer communities,

since they have many goods and services to buy; their marginal propensity to

consume is larger.

1.2. c Disposable income

People can either spend or save their disposable income. When

people are very poor, they cannot afford to save. All of their disposable

income will be spent on buying basic necessities to survive. In fact, some may

have to spend more of their income in order to be able to buy enough food and

clothing and pay for housing.

When people spend more than their income, they are said to be

dissaving. This is because they are either drawing on their past saving or more

likely, borrowing other people's savings. As income rises people are able, to

both spend and save more. As people become richer they buy more and better

quality products. It is interesting to note, however, that whilst the total

amount spent rises with income, the proportion spent tends to fall. For

example: A top class footballer in Rwanda may earn a disposable income of

150,000 Frw a month whilst an unemployed person in Rwanda may live on benefits

of 15,000 Frw a month.

The unemployed person may spend all of the 15000 Frw. The

footballer can clearly afford to spend more and is likely to do so. However,

even if he has a very luxurious lifestyle, it is unlikely that he will spend

all of the 150,000 Frw. If he spends 100,000Frw (a huge amount) he will only be

spending 80% of his disposable income, whilst the unemployed person is spending

100% of his income.

The proportion of income which people spend is sometimes

referred to as the average propensity to consume (APC). It is calculated by

dividing consumption by disposable income. As income rises, expenditure

increases but the APC falls.

13

1.3 National income

National income is an uncertain term which is used

interchangeably with national dividend, national output and national

expenditure. On this basis, national income has been defined in a number of

ways. Commonly, national income means the total value of goods and services

produced annually in a country. In other words, the total amount of income

accruing to a country from economic activities in a year's time is known as

national income.

It includes payments made to all resources in the form of

wages, interest, rent and profits. In this variable, we shall be giving the

detail containing, definitions of national income, concepts of national income,

methods of measuring, national income, difficulties or limitations in measuring

national income, importance of, national income analysis as well as the

inter-relationship among different concept of national Income.

1.3.a. Definitions of National Income:

The definitions of national income can be grouped into two

classes: One, the traditional definitions advanced by Marshall, Pigou and

Fisher; and two, modern definitions. According to Marshall «The agents of

production: Land, labor and capital and organization a country acting on its

natural resources produce annually a certain net aggregate of commodities,

material and immaterial including services of all kinds. This is the true net

annual income or revenue of the country or national dividend.» In this

definition, the word `net' refers to deductions from the gross national income

in respect of depreciation and wearing out of machines. And to this, must be

added income from abroad.

Though the definition advanced by Marshall is simple and

comprehensive, yet it suffers from a number of limitations. First, in the

present day world, so varied and numerous are the goods and services produced

that it is very difficult to have a correct estimation of them. Consequently,

the national income cannot be calculated correctly. Second, there always exists

the fear of the mistake of double counting, and hence the national income

cannot be correctly estimated. Double counting means that a particular

commodity or service like raw material or labor, etc. might get included in the

national income twice or more than twice.

For example, a peasant sells wheat worth .200,000 frw to a

flour mill which sells wheat flour to the wholesaler and the wholesaler sells

it to the retailer who, in turn, sells it to the customers. If each time, this

wheat or its flour is taken into consideration, it will work out to Rs.800, 000

Frw, whereas, in actuality, there is only an increase of .200, 000 Frw in the

national income. Third, it is again not possible

14

to have a correct estimation of national income because many

of the commodities produced are not marketed and the producer either keeps the

production for self-consumption or exchanges it for other commodities.

The Pigouvian Definition:

Arthur Cecil Pigou in the field of Welfare economics

has, in his definition of national income, included that income which

can be measured in terms of money. In the words of Pigou, «National income

is that part of objective income of the community, including of course income

derived from abroad which can be measured in money. This definition is better

than the Marshallian definition. It has proved to be more practical also. While

calculating the national income nowadays, estimates are prepared in accordance

with the two criteria laid down in this definition. First, avoiding double

counting, the goods and services which can be measured in money are included in

national income. Second, income received on account of investment in foreign

countries is included in national income. The Pigouvian definition is precise,

simple and practical but it is not free from criticism. First, in the light of

the definition put forth by Pigou, we have to unnecessarily differentiate

between commodities which can and which cannot be exchanged for money.

Nevertheless, actually there is no difference in the

fundamental forms of such commodities; no matter they can be exchanged for

money. Second, according to this definition when only such commodities as can

be exchanged for money are included in estimation of national income, the

national income cannot be correctly measured. According to Pigou, a woman's

services as a nurse would be included in national income but excluded when she

worked in the home to look after her children because she did not receive any

salary for it. Similarly, Pigou is of the view that if a man marries his lady

secretary, the national income diminishes as he has no longer to pay for her

services.

Thus the Pigovian definition gives rise to a number of

paradoxes. Third, the definition is applicable only to the developed countries

where goods and services are exchanged for money in the market. According to

this definition, in the backward and underdeveloped countries of the world,

where a major portion of the produce is simply bartered, correct estimate of

national income will not be possible, because it will always work out less than

the real level of income. Thus the definition advanced by Pigou has a limited

scope.

15

Fisher's Definition:

Irving Fisher adopted `consumption' as the

criterion of national income whereas Marshall and Pigou regarded it to be

production. According to Fisher, «The National dividend or income consists

solely of services as received by ultimate consumers, whether from their

material or from the human environments. Thus, a piano, or an overcoat made for

me this year is not a part of this year's income, but an addition to the

capital. Only the services rendered to me during this year by these things are

income. Fisher's definition is considered to be better than that of Marshall or

Pigou, because Fisher's definition provides an adequate concept of economic

welfare which is dependent on consumption and consumption represents our

standard of living. But from the practical point of view, this definition is

less useful, because there are certain difficulties in measuring the goods and

services in terms of money. First, it is more difficult to estimate the money

value of net consumption than that of net production. In one country there are

several individuals who consume a particular good and that too at different

places and, therefore, it is very difficult to estimate their total consumption

in terms of money. Second, certain consumption goods are durable and last for

many years.

If we consider the example of piano or overcoat, as given by

Fisher, only the services rendered for use during one year by them will be

included in income. If an overcoat costs 20,000frw and lasts for ten years,

Fisher will take into account only 20,000 frw as national income during one

year, whereas Marshall and Pigou will include 20,000 frw in the national income

for the year, when it is made. Besides, it cannot be said with certainty that

the overcoat will last only for ten years. It may last longer or for a shorter

period. Third, the durable goods generally keep changing hands leading to a

change in their ownership and value too. It, therefore, becomes difficult to

measure in money the service-value of these goods from the point of view of

consumption.

Modern Definitions:

From the modern point of view, Simon Kuznets

has defined national income as «the net output of commodities and services

flowing during the year from the country's productive system in the hands of

the ultimate consumers. On the other hand, in one of the reports of United

Nations, national income has been defined on the basis of the systems of

estimating national income, as net national product, as addition to the shares

of different factors, and as net national expenditure in a country in a year's

time. In practice, while estimating national income, any of these three

definitions may be adopted.

16

1.3.b Concepts of National Income:

There are a number of concepts pertaining to national income

and methods of measurement relating to them. Gross Domestic Product

(GDP): J.M Keynes Defines GDP as the total value of goods and services

produced within the country during a year. This is calculated at market prices

and is known as GDP at market prices. The Governments always plans to spend

during fiscal year therefore, a reduction in planned expenditure decreases the

level of income (GDP). GDP at market price is «the market value of the

output of final goods and services produced in the domestic territory of a

country during an accounting year.» There are three different ways to

measure GDP: Product method, Income method and Expenditure

method, these three methods of calculating GDP yield the same result

because:

National Product = National Income = National

Expenditure.

Product Method: In this method, the value of

all goods and services produced in different industries during the year is

added up. This is also known as the value added method to GDP or GDP at factor

cost by industry of origin.

The Income Method: The people of a country

who produce GDP during a year receive incomes from their work. Thus GDP by

income method is the sum of all factor incomes: Wages and Salaries

(compensation of employees) + Rent + Interest + Profit.

Expenditure Method: This method focuses on

goods and services produced within the country during one year. GDP by

expenditure method includes:

(i) Consumer expenditure on services, durable and non-durable

goods (C)

(ii) Investment in fixed capital such as residential and

non-residential building, machinery, and inventories (I),

(iii) Government expenditure on final goods and services

(G),

(iv) Export of goods and services produced by the people of

country (X),

(v) Less imports (M). That part of consumption, investment

and government expenditure which is spent on imports is subtracted from GDP.

Similarly, any imported component, such as raw materials, which is used in the

manufacture of export goods, is also excluded.

Thus GDP by expenditure method at market prices = C+ I + G + (X -

M), where (X-M) is net export which can be positive or negative.

GDP at Factor Cost: It is the sum of net value added by all producers

within the country. Since the net value added gets distributed as income to the

owners of factors of production, GDP is the sum of domestic factor incomes and

fixed capital consumption (or depreciation). Thus GDP at Factor Cost =

Net value added + Depreciation.

17

GDP at factor cost includes:

(i) Compensation of employees i.e., wages, salaries, etc.

(ii) Operating surplus which is the business profit of both

incorporated and unincorporated firms. [Operating Surplus = Gross Value Added

at Factor Cost--Compensation of Employees--Depreciation]

(iii) Mixed Income of Self- employed. Conceptually, GDP at

factor cost and GDP at market price must be identical. This is because the

factor cost (payments to factors) of producing goods must equal the final value

of goods and services at market prices. However, the market value of goods and

services is different from the earnings of the factors of production. In GDP at

market price are included indirect taxes and are excluded subsidies by the

government. Therefore, in order to arrive at GDP at factor cost, indirect taxes

are subtracted and subsidies are added to GDP at market price. Thus, GDP at

Factor Cost = GDP at Market Price - Indirect Taxes + Subsidies.

Net Domestic Product (NDP):

NDP is the value of net output of the economy during the year.

Some of the country's capital equipment wears out or becomes obsolete each year

during the production process. The value of this capital consumption is some

percentage of gross investment which is deducted from GDP. Thus Net Domestic

Product = GDP at Factor Cost-Depreciation.

Nominal and Real GDP:

When GDP is measured on the basis of current price, it is

called GDP at current prices or nominal GDP. On the other hand, when GDP is

calculated on the basis of fixed prices in some year, it is called GDP at

constant prices or real GDP. Nominal GDP is the value of goods and services

produced in a year and measured in terms of money at current (market) prices.

In comparing one year with another, we are faced with the problem that is not a

stable measure of purchasing power. GDP may rise a great deal in a year, not

because the economy has been growing rapidly but because of rise in prices (or

inflation). On the contrary, GDP may increase as a result of fall in prices in

a year but actually it may be less as compared to the last year. In both 5

cases, GDP does not show the real state of the economy. To rectify the

underestimation and overestimation of GDP, we need a measure that adjusts for

rising and falling prices. This can be done by measuring GDP at constant prices

which is called real GDP. To find out the real GDP, a base year is chosen when

the general price level is normal, i.e., it is neither too high nor too low.

The prices are set to 100 (or 1) in the base year.

Now the general price level of the year for which real GDP is

to be calculated is related to the base year on the basis of the following

formula which is called the deflator index.

18

GDP Deflator:

GDP deflator is an index of price changes of goods and

services included in GDP. It is a price index which is calculated by dividing

the nominal GDP in a given year by the real GDP for the same year and

multiplying it by 100. Gross National Product (GNP): GNP is the total measure

of the flow of goods and services at market value resulting from current

production during a year in a country, including net income from abroad. GNP

includes four types of final goods and services:

(i) Consumers' goods and services to satisfy the immediate wants

of the people;

(ii) Gross private domestic investment in capital goods

consisting of fixed capital formation, residential construction and inventories

of finished and unfinished goods;

(iii) Goods and services produced by the government; and

(iv) Net export of goods and services, i.e., the difference

between value of exports and imports of goods and services, known as net income

from abroad. In this concept of GNP, there are certain factors that have to be

taken into consideration: First, GNP is the measure of money, in which all

kinds of goods and services produced in a country during one year are measured

in terms of money at current prices and then added together. But in this

manner, due to an increase or decrease in the prices, the GNP shows a rise or

decline, which may not be real. The net National Product All this process is

termed depreciation or capital consumption allowance. In order to arrive at

NNP, we deduct depreciation from GNP. The word `net' refers to the exclusion of

that part of total output which represents depreciation. So NNP =

GNP-Depreciation.

NNP at Market Prices:

Net National Product at market prices is the net value of

final goods and services evaluated at market prices in the course of one year

in a country. If we deduct depreciation from GNP at market prices, we get NNP

at market prices. So NNP at Market Prices = GNP at Market

Prices-Depreciation.

NNP at Factor Cost:

Net National Product at factor cost is the net output

evaluated at factor prices. It includes income earned by factors of production

through participation in the production process such as wages and salaries,

rents, profits, etc. It is also called National Income. This measure differs

from NNP at market prices in that indirect taxes are deducted and subsidies are

added to NNP at market prices in order to arrive at NNP at factor cost. Thus

NNP at Factor Cost = NNP at Market Prices-Indirect taxes+ Subsidies

= GNP at Market Prices - Depreciation-Indirect taxes +

Subsidies.= National Income.

19

Normally, NNP at market prices is higher than NNP at factor

cost because indirect taxes exceed government subsidies. However, NNP at market

prices can be less than NNP at factor cost when government subsidies exceed

indirect taxes. Normally, there are a wide number of theories of National

Income and many economists are interested in discussing about such variable.

This study combines of number of theories and these will help the researcher to

maximize analysis on National income n Rwanda.

1.4 Interest rate

Interest rate is the amount charged, expressed as a percentage

of principal, by a lender to a borrower for the use of assets. Interest rates

are typically noted on an annual basis, known as the annual percentage rate

(APR). It was found the lending interest rate is determined by the funding

cost, the loan size, and the efficiency level of microfinances.

Lending rate is the bank rate that usually meets the short- and

medium-term financing needs of the private sector. This rate is normally

differentiated according to creditworthiness of borrowers and objectives of

financing. Interest is money paid by a borrower to a lender for a credit or a

similar liability. It is the charge for the privilege of borrowing money.

Important examples are bond yields, interest paid for bank loans, and returns

on savings. A modern economy is intrinsically linked to interest rates, thus

their importance on the financial markets. Interest rates affect consumer

spending. The higher the rate, the higher their loans will cost them, and the

less they will be able to buy on credit. Interest rates are classified many we

can state: Nominal interest rate, real interest rate, effective interest rate,

and so on.

1.4. a. Nominal Interest Rate

The nominal interest rate is conceptually the simplest type of

interest rate. It is quite simply the stated interest rate of a given bond or

loan. This type of interest rate is referred to as the coupon rate for fixed

income investments, as it is the interest rate guaranteed by the issuer that

was traditionally stamped on the coupons that were redeemed by the

bondholders.

The nominal interest rate is in essence the actual monetary

price that borrowers pay to lenders to use their money. If the nominal rate on

a loan is 5%, then borrowers can expect to pay 5000 frw of interest for every

100,000 frw loaned to them.

20

1.4.b Real Interest Rate

The real interest rate is slightly more complex than the

nominal rate but still fairly simple. The nominal interest rate doesn't tell

the whole story because inflation reduces the lender's or investor's purchasing

power so that they cannot buy the same amount of goods or services at payoff or

maturity with a given amount of money as they can now.

The real interest rate is so named because it states the

«real» rate that the lender or investor receives after inflation is

factored in; that is, the interest rate that exceeds the inflation rate. If a

bond that compounds annually has a 6% nominal yield and the inflation rate is

4%, then the real rate of interest is only 2%. So Nominal interest

rate - Inflation = Real interest rate.

1.4. c Effective interest rate

One other type of interest rate that investors and borrowers

should know is called the effective rate, which takes the power of compounding

into account.

1.5. Inflation rate

Inflation is the rate at which the general level of prices for

goods and services is rising, and, subsequently, purchasing power is falling.

Central banks attempt to stop severe inflation, along with severe deflation, in

an attempt to keep the excessive growth of prices to a minimum. Inflation is a

state of economy in which the general prices of commodities and services become

high. Another way we can say that «too much money chasing too few

goods». The so called consumer price indices are prominently used to

calculate inflation. An increase in the money supply may be called monetary

inflation, to distinguish it from rising prices, which may also for clarity be

called "price inflation". Economists generally agree that in the long run,

inflation is caused by increases in the money supply. Inflationary problems

arise when we experience unexpected inflation which is not adequately matched

by a rise in people's incomes. If incomes do not increase along with the prices

of goods, everyone's purchasing power has been effectively reduced, which can

in turn lead to a slowing or stagnant economy. So someone can ask himself what

exactly causes inflation in an economy. There is not a single, agreed-upon

answer, but there are a variety of theories, all of which play some role in

inflation:

21

1.5.1. Causes of inflation

1.5.1.a. The cost push-inflation (On the supply

side)

Inflation is primarily caused by an increase in the money

supply that outpaces economic growth. Ever since industrialized nations moved

away from the gold standard during the past century, the value of money is

determined by the amount of currency that is in circulation and the public's

perception of the value of that money. When the Central Bank decides to put

more money into circulation at a rate higher than the economy's growth rate,

the value of money can fall because of the changing public perception of the

value of the underlying currency. As a result, this devaluation will force

prices to rise due to the fact that each unit of currency is now worth less.

The same logic works for currency; the less currency there is in the money

supply, the more valuable that currency will be. When a government decides to

print new currency, they essentially water down the value of the money already

in circulation. A more macroeconomic way of looking at the negative effects of

an increased money supply is that there will be more Rwandan currency chasing

the same amount of goods in economy which will inevitably lead to increased

demand and therefore higher prices.

Cost-Push Effect

Another factor in driving up prices of consumer goods and

services is explained by an economic theory known as the `cost-push

effect'. Essentially, this theory states that when companies are

faced with increased input costs like raw goods and materials or wages, they

will preserve their profitability by passing this increased cost of production

onto the consumer in the form of higher prices. Inflation can be categorized

into many but the most current ones are: Demand Pull Inflation this is a kind

of inflation that occurs on demand side where the demand for goods and services

exceed the supply.

Cost Push Inflation: this is a kind of inflation that occurs

on the supply side where price increases due to an increase in price of other

products.

22

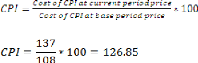

Calculation of Inflation

For example, CPI on Jan 1, 2013 is 125 and that on Jan 1, 2014

is 133.75 then inflation for the year 2014 would be:

Or:

Therefore:

The National Debt

In economics, the reason for this is that if there is a

country's debt increases, the government has two options: it can either raise

taxes or print more money to pay off the debt. A rise in taxes will cause

businesses to react by raising their prices to offset the increased corporate

tax rate. Alternatively, should the government choose the latter option,

printing more money will lead directly to an increase in the money supply,

which will in turn lead to the devaluation of the currency and increased

prices.

1.5.1. b Demand-Pull Inflation (On the demand side)

The demand-pull effect states that as wages increase within an

economic system (often the case in a growing economy with low unemployment),

people will have more money to spend on consumer goods. This increase in

liquidity and demand for consumer goods results in an increase in demand for

products. As a result of the increased demand, companies will raise prices to

the level the consumer will bear in order to balance supply and demand. An

example would be a huge increase in consumer demand for a product or service

that the public determines to be cheap. For instance, when hourly wages

increase, many people may determine to undertake home improvement projects.

This increased demand for home improvement goods and services will result in

price increases by house-painters, electricians, and other general contractors

in order to offset the increased demand. This will in turn drive up prices

across the board.

23

1.5.2 Keynesian inflation theory

The eminent economist John Maynard Keynes

theorized a lot about inflation. He postulated that the money supply

had an influence on inflation in a much more complex way than the strict

monetarists suggested. Instead Keynes proposed that inflation was caused in

number of different ways: By demand outstripping supply and pulling inflation

higher, by inflation being built into the system, by higher costs pushing

inflation higher. Below are examples of each of these types of causes of

inflation.

Source: Kahn R (1976) `Inflation-Keynesian View' Scottish

Journal of political Economy: London, UK Figure 1: Inflation Keynesian

View

It was also Keynes's view that inflation expectations were

important. They impact the wage settlements that workers seek and affect other

inflation agreements that are created. These can have a marked effect on future

inflation rates. Furthermore Keynes and his followers have argued that

governments face a trade-off between unemployment and inflation i.e. if you

want full employment you may need to tolerate higher inflation. Indeed, as

Keynes was writing during the Great Depression

(1929-1933), he not surprisingly gave great importance to

reducing unemployment. This thinking paved the way for post-war governments

that were less concerned about creating inflation than their predecessors, as

they saw it as a necessary trade-off to create full employment. It is

interesting that the Keynesian theory of inflation has gone out of fashion.

This is probably related to the rejection of Keynesian thinking in

general which started in the 1970s. However Keynesian ideas

have had something of a renaissance following the Great Recession of 2008 as

governments seek alternative solutions to the problems we now face.

1.6. Exchange rates

The exchange rate between two countries is the price which

residents of those countries trade with each other. Economists distinguish

between two exchange rates: Nominal exchange rate and Real exchange rate.

1.6. a. Nominal exchange rate (e)

This is the relative price of the currency of two countries.

In other words, the nominal exchange rate is the rate at which one currency

trades against another on the foreign exchange market. The nominal exchange

rate e is defined again as the number of units of the domestic currency that

can purchase a unit of a given foreign currency. A decrease in this variable is

termed nominal appreciation of the currency. (Under the fixed exchange rate

regime, a downward adjustment of the rate e is termed revaluation.) An increase

in this variable is termed nominal depreciation of the currency. (Under the

fixed exchange rate regime, an upward adjustment of the nominal rate e

is called devaluation). When people refer to the exchange rate between

two countries, they usually mean the nominal exchange rate. So the nominal

exchange rate can be expressed as:

1.6.b. Real exchange rate (å)

This is the relative price of the goods of two countries. It

tells us the rate at which we can trade the goods of one country for good of

another. The real exchange rate R is defined as the ratio of the price level

abroad and the domestic price level, where the foreign price level is converted

into domestic currency units via the current nominal exchange rate.

24

Where

25

å= Real exchange rate

P* = Price of foreign good

P= Price of domestic good

e= Nominal exchange rate

A decrease in å is termed appreciation of the real

exchange rate, an increase is termed depreciation. The real rate tells how many

times more or less goods and services can be purchased abroad (after conversion

into a foreign currency) than in the domestic market for a given amount. In

practice, changes of the real exchange rate rather than its absolute level are

important. In contrast to the nominal exchange rate, the real exchange rate is

always »floating», since even in the regime of a fixed nominal

exchange rate e, the real exchange rate å

can move via price level changes. Normally, it is the nominal exchange

rate adjusted for inflation. Unlike most other real variables, this adjustment

requires accounting for price levels in two currencies. Standard models of

international risk sharing with complete asset markets predict a positive

association between relative consumption growth and real exchange-rate

depreciation across countries. The striking lack of evidence for this link the

consumption/real-exchange-rate anomaly or `Backus-Smith

puzzle' has prompted research on risk-sharing indicators with

incomplete asset markets. That research generally implies that the association

holds in forecasts, rather than realizations. Independent evidence on the weak

link between forecasts for consumption and real interest rates suggests that

the presence of 'hand-to-mouth' consumers may help to resolve the anomaly.

Developed by James Duesenberry(1946), the relative income hypothesis states

that an individual's attitude to consumption and saving is dictated more by his

income in relation to others than by abstract standard of living; the

percentage of income consumed by an individual depends on his percentile

position within the income.

It is reasonable to say that Adam Smith (1776) has played an

important role in the development of welfare theory. The reasons are at least

two: In the first place, he created the invisible hand idea that is one of the

most fundamental equilibrating relations in economic theory, the equalization

of rates of returns as enforces by a tendency of factors to move from low to

high returns through the allocations of capital to individual industries by

self-interested investors. The self-interest will results in an optimal

allocation of capital for society. He writes: «every individual is

continually exerting himself to find out the most advantageous employment for

whatever capita he can command. It is his advantage, indeed, and not that of

society, which he has in view. But the study of his own advantage naturally, or

rather necessarily leads him to prefer that employment which is most

advantageous to society». Adam Smith does not stop there but notes that

what is true for investment is true in economic activity in general.

26

«Every individual necessarily labors to render the annual

revenues of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither

intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much is promoting

it» He concludes: «It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the

brewer or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from the regards of their

own interest». The most famous line is probably the following: The

individual is led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of

his own intention. The invisible hand is competition and this ides was present

already in the work of the brilliant and undervalued Irish economist

Richard Cantillon. He sees the invisible hand as embodied in

the central planner, guiding the economy to social optimum.

The second reason why Adam Smith played an important role in

the development of welfare theory is that, an attempt to explain the

«Water and Diamond Paradox», he came across an

important distinction in value theory. At the end of the fourth chapter of the

first book in Adam Smith's celebrated volume The Wealth of Nations

(1776), he brings up a valuation problem that is usually referred

to as the Value Paradox2. He writes.

27

CHAPTER 2: ANALYSIS OF THE STATUS AND TRENDS OF

DETERMINANTS

AFFECTING AGGREGATE CONSUMPTION EXPENDITUTE IN

RWANDA

2.0 INTRODUCTION

In this chapter, the researcher analyzed the trends of

consumption and its determinants. Using tables and graphs to describe the

variable, the researcher tested the first hypothesis of these variables and

found that gross consumption expenditure and its associates have the upward

evolution. From the post-Genocide period, the wellbeing of people in the

country increased gradually. Policies to enhance the standards of living of

people in different economic sectors have been put into action.

2.1. Evolution of gross consumption expenditure in Rwanda

1995-2015

James Duesenberry (1946) in his relative income hypothesis

rejected the fundamental assumption of consumption theory of Keynes. He

challenged the assumption of the independence of individual's consumption and

postulated interdependence in consumption behavior. He posited that consumption

behavior is not independent but interdependent on the behavior of every other

individual. He explained that people do not only derive satisfaction from

consumption but also from how the consumption compares with that of others.

(Ahuja: 2013).

As such, the relative size of a household income to that of

other households determines consumption level. The hypothesis is based on three

relative aspects:

? A household's income position is relative

to its associates or group to which it belongs.

? A household's present income is relative to

its previous incomes.

? The wellbeing of society depends on

Government intervention through economic measures.

By this, he posited that households strive constantly toward a

higher consumption level and emulate the consumption pattern of a neighbor.

(Ohale: 2002).If income of all individuals/household increases by the same

percentage, and then relative income would remain the same despite the increase

in absolute income. Since the relative income remains the same, the same

proportion of income would still be spent on consumption, Average Propensity to

Consume (APC) will thus, remain the same. To capture the determinant of

aggregate consumption expenditure in Rwanda, the following model has been

specified by the researcher: GCE= f(Y, INT, INF, and EXR).Where GCE = Gross

Consumption Expenditure Y= Income (GDP), INT= Interest Rate, INF= Inflation

Rate, EXR= Foreign Exchange Rate.

28

Thus, GCE= â0

+â1GDP+â2INT+â3INF+â4EXR+u

Where: â0>0, â1>0,

â2><0, â3<0, â4<0

? Gross Consumption Expenditure proxied by GCE

is the consumption without tax or other contributions having been

deducted. In other words, it is the consumption at current prices used by

household in the community.

? Income: The researcher used GDP

as a proxy for income. A positive sign is expected as there is a

direct relationship between consumption and income. Consumption expenditure is

expected to increase with an increase in income.

? Interest Rate: (Proxied by

INT) an increase in lending interest rate may lead to a

decrease or increase in consumption. As such, the expected sign was determined

by researcher findings.

? Inflation Rate: we use INF

as a prosy of inflation rate. This tries to capture the effect of

increase in price level of consumption. When there is inflation (general price

level increase), the real value of the consumer's cash balance is falls. As

such their purchasing power is hampered, leading to a fall in consumption

expenditure. Thus an inverse relationship is expected to occur between

inflation and consumption; therefore, the researcher interpreted this

hypothesis regression.

? Exchange Rate: The researcher used

EXCHR as a proxy of exchange rate. The researcher attempted to

capture how households react to changes in price of foreign goods by including

exchange rate of Rwandan currency to dollar in the used model. This stems from

the fact that about 1837.3 b Frw of consumer goods is imported

from foreign countries which include food items, services, automobiles, etc.

While Exported goods are 846.15 b Frw. Thus the expected sign

of the relationship between exchange rate and consumption expenditure shown by

the researcher after regression. To estimate the results, the researcher

employed the ordinary least square (OLS) method of estimation to check for

variables that determine consumption.

29

WORLD BANK DATA USED BY RESEARCHER

|

Year

|

GDP

|

EXCH

|

CPI

|

GCE

|

|

1995

|

338.21

|

262.18

|

37.5

|

327.73

|

|

1996

|

423.41

|

306.82

|

40.07

|

398.87

|

|

1997

|

557.83

|

301.53

|

44.88

|

527.68

|

|

1998

|

621.49

|

312.31

|

47.67

|

577.77

|

|

1999

|

607.77

|

333.94

|

46.52

|

554.34

|

|

2000

|

674.18

|

389.7

|