|

|

WOMEN'S UNIVERSITY IN AFRICA

|

|

|

RESEARCH TITLE

$

Impact of Foreign Aid on Rwanda's Socio-Economic

Development

as guided by Millennium Development Goal (MDG)

1

«Eradication of extreme poverty and hunger»:

The

case of Gasabo District

R

R

By

R

Claire Marie Michele MUKARUTESI

Reg. No:WSS0401090004

R

A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES

IN

PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE MASTER

OF

SCIENCE IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES DEGREE (MDS)

R R

R R

R

HARARE, ZIMBABWE, 2011

|

|

DECLARATION

I hereby certify that this thesis entitled

«The impact of Foreign Aid on Rwanda's socioeconomic

Development as guided by Millennium Development Goal 1» is

entirely my own work, except where stated otherwise, and that it has not been

submitted for any other degree or professional qualification.

Claire Marie Michele MUKARUTESI May 2011

RELEASED FORM

Name of Author: Claire Marie Michele

MUKARUTESI

Title of project: The impact of Foreign Aid

on Rwanda?s Socio-Economic Development as guided by Millennium Development Goal

(MDG) 1 «Eradication of extreme poverty and hunger»: The case of

Gasabo District.

Programme for which project was presented:

Master of Science in Development Studies Degree

Year granted: 2011

Permission is hereby granted to the Women?s University in

Africa library to produce single copies of this project and to lend or sell

such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. The

author reserves other publication rights and neither the project printed or

otherwise reproduced without the author?s written permission.

Signed:

Permanent Address: A2 Ramis Court, Kileleshwa,

Nairobi-Kenya

APPROVAL FORM

The undersigned certify that they have read and recommended to

the Women?s University in Africa for acceptance, a project entitled, «The

impact of Foreign Aid on Rwanda?s SocioEconomic Development as Guided by

Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 1 - Eradication of extreme poverty and

hunger»: The case of Gasabo District, submitted by Claire Marie

Michele MUKARUTESI in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the

Master of Science Degree in Development Studies.

.................................................................

SUPERVISOR

................................................................................................

PROGRAMME COORDINATOR

.........................................................................

EXTERNAL EXAMINER

DATE:

DEDICATION

This research is dedicated to my husband Maurice A. KAMANZI,

my children Rita Gloria O. IHIRWE, Omer Herve GANZA and Pedro ISHIMWE KAMANZI

for bearing up with me when I could not be there for them, you are the epitome

of God?s faithfulness in my life, I LOVE YOU GUYS!!!

My profound gratitude goes to all people who immensely

contributed to the success of this study. All the assistance and support given

is highly appreciated. May God bless you.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First and foremost, I would like to thank the God Almighty,

for creating the human being that I am, that He cares for and protects so

dearly.

This thesis to be what it is, it could not have been possible

without the input of a huge number of people. Many people within government

departments, civil society organisations and academic institutions in Rwanda

and Zimbabwe, gave up enormous amounts of time to assist me in gathering data,

in establishing contacts and in working through my ideas. This research was

made possible by the collaboration of so many staff in Rwanda?s Ministry of

Finance and Economic Planning, Ministry of Local Government, Gasabo District

and Donor Community in Rwanda, please accept my gratitude. My gratitude goes to

all respondents from the research areas, for participating and sharing their

experiences. I would particularly like to thank the Management of Rwanda

Development Bank-BRD for allowing me to conduct my research into the

Institution.

I would like to extend my profound gratitude to my supervisor,

Mr O. Nyaude for his patience and commitment in assisting me in shaping an

idea, and an aspiration into reality. Without your encouragement, constructive

criticism, and academic prowess, this project would have been done properly.

Many thanks go to the Women?s University in Africa, to the Faculty of Social

Science, Department of Development Studies.

Throughout this research my husband Maurice KAMANZI has given

me just the right mix of encouragement and criticism at all the right times, I

do not have words to appreciate your invaluable input I am indebted to you for

that; My children Rita Gloria O IHIRWE K., Omer Herve GANZA K., Pedro ISHIMWE

KAMANZI, Thank for your understanding, support and love during this strenuous

period- I love you more for that!!!

Finally, I want to thank my Mother, brother, Sisters and

friends Vedaste Kalima and Immacullee Nyiraminani, who have encouraged me

throughout this process. Without your support and your constant faith in me

this research would never have happened.

ABSTRACT

The aim of the study was to investigate and assess the

impact of foreign aid on Rwanda?s socioeconomic development as guided by

Millennium Development Goal (MDG1) To eradicate extreme poverty and

hunger?. The study was undertaken with selected respondents drawn from Gasabo

District of the Kigali City in the Republic of Rwanda (a

developing nation in East Africa).

Both qualitative and quantitative research approaches were

used. Data were collected by means

of interviews, observational schedules, documentary

analysis procedures, questionnaires and Focus Group Discussion (FGDs) schedules

from a total of one hundred and fifty (150) respondents. Nine (9) of these were

Heads of departments/administrators. The study found that the majority of the

respondents perceived foreign aid as pivotal in promoting socio-economic

development of any given developing country. The eradication of poverty

in society was viewed as a worthwhile undertaking and helps address

socio-economic problems. They hailed the need to understand the scope of MDGs

and its need to be included in the various Rwandan curriculum

However the study established that there are mixed feelings

with regard the impact of foreign

aid, its challenges and prospects in general in light of

the need to fight the global poverty within the confines of MDGs. They felt

that the knowledge of MDGs must be a central component of Rwanda?s

civic/citizenship education in order to develop a common understanding of the

quest to eradicate poverty and spearhead all-encompassing development. The

study concludes that foreign aid is at the core of successfully eradicating

extreme poverty and hunger, though it must be received with some caution as a

number of donor agencies will end up politicizing the concept

thus attaching strings and conditionalities to

beneficiaries/recipients.

The study recommends that there is great need to expose

citizens to issues relating to foreign aid,

poverty alleviation and development discourse pupils at a

tender age. The study further

recommends the intensification of the training programmes for

citizens to be able to handle the

issues linked to aid. Furthermore research is recommended in

this seemingly grey area in line with the dynamic aspect of development and

education respectively.

LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES

Figures

Figure 2.1 : Aid Coordination Architecture in Rwanda

Figure 3.1 : New Administrative Map of Gasabo District

Figure 4.1 : Gendered perceptions on poverty as Rwanda?s threat

to socio-economic development

Figure 4.2 : Perceptions of the impact of Foreign Aid on the

Rwandan economy Figure 4.3 : Gendered perceptions of Foreign Aid and

dependency

Figure 4.4 : Knowledge of the existence of MDGs in Rwanda Figure

4.5 : Ranking of MDGs according to priority

Figure 4.6 : Rating of Poverty Eradication Strategies

Figure 4.7 : Perceptions of beneficiaries of Foreign Aid in

Rwanda

Figure 4.8 : Relations of the Government of Rwanda and the Donor

Community Figure 4.9 : Beneficiaries of Donor Community from 2000-2009

Figure 4.10: Challenges with regards to Implementation of MDGs

Figure 4.11: Ranking Rwanda?s main Resources in order of importance Figure

4.12: Composition of External Resources

Tables

Table 3.1 : Sampling Systems

Table 4.1 : Views on whether poverty is a threat to Rwanda?s

socio-economic development by organizations

Table 4.2 : Views on whether poverty has functional benefits to

society

Table 4.3 : Views on whether Foreign Aid creates dependency on

Rwanda by Organization Table 4.4 : SustainabilIIVERIEIRTJUQE$ I3EtQE5

Zto31?sE

Socio-economic development

Table 4.5 : Availability of technical challenges with regards

to implementation of MDGs

Table 4.6 : Data gathered using interview methods

Table 4.7 : Documentary Analysis Procedures

Table 4.8 : NGOs/2010 registered in Gasabo District

Table 4.9 : Estimates of different budgetary sources

LIST OF APPENDICES

Appendix 1 : Map of Rwanda

Appendix 2 : Approval letter from WUA, BRD and Letter from DFID

Appendix 3 : Rwanda Development Partners by Sector

Appendix 4 : Coordination Questionnaires, Interview and FGDs

ACRONYMS

AfDB African Development Bank

BRD Rwanda Development Bank

BS Budget Support

BSHG Budget Support Harmonisation Group

BTC Belgian Technical Cooperation

CBEP Capacity Building and Employment

Promotion

CDF Common Development Fund (Rwanda)

CEPEX Central Bureau for Public Investments and

External Funding (Rwanda)

DAD Development Assistance Database

DCPETA Decentralization, Citizen Participation,

Empowerment, Transparency and

Accountability

DDLR Donor Division of labour in Rwanda

DFID Department for International Development

(UK)

DPM Development Partners Meeting

DPAF Donor Performance Assessment framework

DRC Democratic Republic of Congo [Zaire until

1997]

EC European Commission

EDPRS Economic Development Poverty Reduction

Strategy

EICV Integral survey on conditions of living

within families

ESAP Economic Structural Adjustment Programme

ESF Economic Support Fund

EU European Union

FAO Food and Agriculture Organisation (UN)

FDI Foreign Direct Investment

FGD Focus Group Discussion

FHHs Female Headed Households

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GNP Gross National Product

GoR Government of Rwanda

HARPP Harmonisation and Alignment in Rwanda of

Projects and Programmes

HDI Human Development Index

HDR Human Development Report

HIPC Heavily Indebted Poor Countries

Initiative

HIV/AIDS Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired

Immunodeficiency Syndrome

ICT Information and Communications Technology

IDA International Development Association (World

Bank)

IFIs International Financial Institutions

IMF International Monetary Fund

IRC International Rescue Committee

JAF Joint Action Forum

JRLO Justice, Reconciliation, Law and Order

LDC Less Developed Countries

MDCs More Developed Counties

MDGs Millennium Development Goals

MINECOFIN Ministry of Finance and Economic

Planning (Rwanda)

MINALOC Ministry of Local Government

MoU Memorandum (Memoranda) of Understanding

MTEF Medium-Term Expenditure Framework

NGO(s) Non-governmental organisation

ODA Official development Assistance

ODI Overseas Development Institute

OECD Organisation for Economic Cooperation and

Development

OECD-DAC Organisation for Economic Cooperation

and Development -

Development Assistance Committee

OFDA Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance

OPEC Organization of Petroleum-Exporting

Countries

Org. Organization

PAS Poverty Assessment Study (Zimbabwe)

PD Paris Declaration

PDD District Development Plan

PFM Public Financial Management (Rwanda)

PRS Poverty Reduction Strategy

PRSP Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper

PRS-PR Poverty Reduction Strategy Progress

Report

RGPH General Registration of the Population and

Housing

RPF Rwanda Patriotic Front

RWACOM Rwanda

RwF Rwandan Francs

SADC Southern African Development Cooperation

SAP Structural Adjustment Programme(s)

SBS Sector Budget Support

SIDA Swedish International Development

Cooperation Agency

SMEs Small and Medium Enterprises

SORWATOM Societe Rwandaise de Tomates

SPPMD Strategic Planning and Poverty Monitoring

Department (Minecofin)

SPSS Strategic Programme of Social Science

UK United Kingdom

UN United Nations

UNDP United Nations Development Programme

UNFEM United Nations Development Fund for

Women

UNICEF 8 cEId NIINWLEIAIMME und

UNWFP United Nations World Food Program

USA United States of America

USAID United States Agency for International

Development

UTEXRWA Usine de Textile au Rwanda

VUP Vision Umurenge Programme

WB World Bank

WHO World Health Progamme

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DECLARATION ii

RELEASED FORM iii

APPROVAL FORM iv

DEDICATION v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vi

ABSTRACT vii

LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES viii

LIST OF APPENDICES x

ACRONYMS xi

TABLE OF CONTENTS xiv

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW 1

1.1 Background to the Study 2

1.2 Statement of the Problem 10

1.3 Research Questions 11

1.4 Objectives of the Study 11

1.5 Assumptions of the Study 12

1.6 Significance and Justification of the Study 13

1.7 Definition of key terms 15

1.8 Delimitation of the Study 16

1.9 Limitations of the study 17

1.10 Organisation of the Study 18

1.11 Chapter summary 19

CHAPTER TWO: REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE 20

2.0 Introduction 20

2.1 Theoretical Frameworks 20

2.2 Conceptualizing aid, development, poverty and hunger 32

2.3 History of Foreign Aid in Rwandan Economy 38

2.3.1 Aid Effectiveness in Rwanda 40

2.3.2 The Politics of Official Development Assistance on Rwanda

42

2.3.3 The World Bank and UNDP Poverty Indicators-Indices 43

2.4 Foreign Aid and Economic Development in LDCs 47

2.4.1 General Global Trends 47

2.4.2 Foreign Aid and Economic Development in Sub-Saharan Africa

51

2.4.3 Challenges Experienced by Government in Making External

Aid Effective 54

2.5 Implications of Literature Review 56

2.6 Chapter summary 58

CHAPTER TRHEE: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 59

3.0 Introduction 59

3.1 Research Design 59

3.1.1 Research Design - An overview 59

3.1.2 Exploratory and Descriptive Phases of the Research Project

60

3.1.3 An overview of the existing situation of the Gasabo

District as the case study 61

3.1.4 Sources of Data 63

3.1.5 Types of data 63

3.1.6 Target Population, Sampling and Sampling Procedures 64

3.2 Data gathering instruments 66

3.2.1 An Overview 66

3.2.2 Structured in-depth Interviews 67

3.2.3 The Questionnaire method 68

3.2.4 Focussed Group Discussions 69

3.2.5 Documentary analysis/content analysis procedures 70

3.2.6 Observational schedules (Participant and non-participant

observation) 71

3.3 Data presentation and analysis 71

3.4 Chapter summary 72

CHAPTER FOUR: DATA PRESENTATION, INTERPRETATION AND ANALYSIS

73

4.0 Introduction 73

4.1 Discussion of questionnaire findings 74

4.1.1 Questionnaire Administration 74

4.1.2 Quali-Quantitative Analysis of Questionnaire Data 74

4.1.3 Overall synthesis of findings from the questionnaire 91

4.2 Qualitative Analysis of Findings 91

4.2.1 Interview data from administrators 92

4.2.2 Data from Observational schedules 100

4.2.3 Documentary Analysis Procedures 104

CHAPTER FIVE: 110

SUMMARIES, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 110

5.0 Introduction 110

5.1 Summary of the major findings 111

5.2 Conclusion of the study 113

5.3 Recommendations for this study 114

REFERENCES 116

ELECTONIC RESOURCES 125

APPENDICES 126

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

The instrumental role of foreign aid on Rwanda?s socio-economic

development has always been

a topical subject of debate am ong scholars, intellectuals,

social scientists and developmentalists

respectively. On one extrem e end, it is argued that foreign aid

is not necessary whereas on the

As such, the attainment of the prime goal of the so-called

Millennium Development Goals

(MDG 1) «To eradicate extreme poverty

and hunger» largely hinges on the foreign support

Rwanda may

happen to receive from various corners of the world. What it entails is that

the

relativity nature of development may generate m ixed feelings to

the extent that people may fail

to arrive at a universal agreement with regard the best way to

attain socio-economic

development.

However, it is the conviction of this study to move a strong

motion that Rwanda?s socioeconomic development entirely depends on the

magnitude at which various stakeholders join hands and aim at eradicating or

seeking the

optimum ways to ameliorate poverty in society. It is therefore

the focus of this study to make a scholarly inquiry into this seemingly grey

area and

ascertain the best possible w ays and strategies to adopt as

Rwanda embarks on this critical

voyage (poverty eradication).

Against this background, it follow s that there is great need to

establish the viable strategies upon

which poverty can be reduced. One fundamental strategy lies in

marrying foreign aid with the available strategies linked to MDGs.

According to World Bank and International Monetary Fund

(WB-IMF, 2002) recommendations, one of the ways of realizing this goal is

provision of aid to less developed countries (LDCs) by more developed countries

(MDCs). Such aid is supported by WB & IMF - directed economic structural

adjustment programs. One may underscore the fact that the various programmes

will be tailor-made to focus on specific developmental targets hence attainment

of socio-economic development in some way.

The pivotal or multi-million dollar question that arises then

is: to what extent can such conditional aid contribute to the

socio-economic development of the host country in the long run? And to

answer this question, one needs to remember what Mushi (1982:09) says about

positive aid: that «aid is developmental only if it lays the foundation

for its future rejection». That is to say aid is only truly useful if in

the long run it promises and guarantees self-reliance and economic

self-sustenance to the beneficiary. Otherwise if aid creates perpetual

dependence then it is not useful at all in the first place. Thus, the dynamic

views associated with foreign aid will eventually make it perceived at varying

degrees of usefulness particularly in developing nations.

1.1 Background to the Study

In Rwanda aid has been coming from various quarters, chief

among them United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and World Bank (WB)

following the genocide. Against this backdrop, the purpose was partly to assist

with reconstruction and also to eradicate poverty and hunger, the latter being

done under the auspices of the MDGs. This study therefore, seeks to

assess whether such aid has a positive or negative impact on the

Rwanda?s socio-economic development by focusing on the particular case of

Gasabo District.

Millennium Development Goal Number 1 clearly states that the

primary spirit behind all

millennium development goals is to: eradicate

extreme poverty and hunger

(

www.developmentgoals.org).

R eduction of global poverty and hunger lies at the core of the

Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The target is to reduce by

half the proportion of

people living on less than US$1 a day in low and middle income

countries - from 28 percent in

1990 to 14 percent in 2015, and halve the

proportion of people who suffer from hunger during

the same period (ibid).

It may seem that the twenty-five year time-frame has elapsed without any

This however will negatively impact on the entire

socio-economic development of Rwanda, hence the need to investigate the

circumstances surrounding the present phenomena. One may observe that, to date

twenty years have passed without any material indication of success. Only five

years rem ain and yet the possibility of achieving this is still a far cry.

Over the years, foreign

aid has been fuelled by both political and economic m otivations

of the ruling classes in the

western donor nations. A classic example is the

United States of America Foreign Aid, the

Marshall Plan [1948-1951] that was aimed at rehabilitating the

shattered economies of Western

Europe, at the same tim e containing the international spread of

communism. When the balance

of Cold War interests shifted from Europe to the World in the

mid-1950s, the policy of containment embodied in the U.S. aid program dictated

a shift in emphasis toward political economic and military support for

«friendly» less developed nations especially those considered

geographically strategic (Todaro, 1983).

Against this backdrop, it follows that the rationale for

foreign aid in general should not be perceived from a lay person?s perspective,

thus it requires some introspection of some sort. Those who offer assistance

primarily consider their chances of benefiting latter even if they commit

themselves to some mammoth task as evidenced in the commitment to eradicate

poverty. In all cases, during the socialist, colonial and post-colonial periods

donor aid was meant to chart the course of globalization and the interests of

global financiers; and this makes donor aid suspicious: whether it really stirs

sustainable development or it simply serves the economic and political

interests of the donor at the expense of host countries. This prompts the need

to find out whether poverty alleviation intervention programmes initiated by

the more developed countries (MDCs) in LDCs are really addressing the needs of

the deserving neediest or not.

Various studies have been carried out around the globe about

whether donors are angels of mercy or doom. As already been alluded to, aid has

been given to LDCs in the spirit of the eight MDGs which can be summarized as

to:

Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

Achieve universal primary education

Promote gender equality and empower women

Reduce child mortality

Improve maternal health

Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases

Ensure environmental sustainability

Develop a global partnership for development (Todaro, 2006:

24)

From the summary, it can be argued that all the other goals

are essentially subordinate and play a complementary role to MDG 1. It follows

that all other goals have a bearing to MDG 1 in one way or the other, implying

that to achieve the target of Goal 1 progress has to be made on the other goals

as well. The irony that global studies have established regarding the

attainment of poverty reduction, however, is that not much progress has been

made. Foreign aid on the other side greatly increases the patronage power of

recipient governments. As Bauer (2008) notes, "The great increase in the prizes

of political power has been a major factor in the frequency and intensity of

political conflict in contemporary Africa and in the rest of the less developed

world, than developmental response. In this respect, foreign aid may be accused

of meddling with the recipient nation?s political issues hence a detrimental

aspect from the sceptics viewpoint. Sceptics are always conscious of their

sovereignty.

UNDP, (2003), advances that in the 1990s income poverty

increased in 37 countries while hunger multiplied in 21 countries. One may

underscore the fact that this cardinal admission with regard the prevalence of

poverty and hunger justifies the great need for foreign aid in countries like

Rwanda. The poorest region in the world, sub-Saharan Africa has the worst

affected countries, seconded by Latin America (ibid). Ethiopia, Rwanda,

Burundi, Botswana, Kenya and Mozambique fall into this category. They have all

been destinations of foreign aid as guided by MDGs. The period under which MDGs

for poverty reduction have been evaluated in Rwanda has been repositioned from

1990 to 2000 following the traumatic upheaval of the 1994 genocide. According

to IRIN News, (2006) initial progress was very slow with 57% of the population

remaining below the national poverty line, assessed in terms of food needs and

non-food essentials.

In that year alone, 37% of the population survived on an

income insufficient to provide the minimum calorie requirement of MDG 1; and

Rwanda experienced one of the highest levels of extreme poverty in the world.

To this effect, the correlation between the existence of peace and the

subsequent attainment of positive development in a nation is largely evidenced

as the so-called genocide had grave and detrimental effects on socio-economic

development; hence the capacity of Rwanda as a sole nation without foreign aid

became hazy. To make matters worse, neither of these poverty rates had fallen

by more than a few points since 2000, despite strong headlines on economic

growth in the media (ibid). Indeed, the Gini coefficient1 measure of

inequality increased over that period from 0.47 to 0.51, a relatively high rate

for East Africa (ibid).

The implication is that the rewards of growth were not

reaching rural households, where 90% of poverty in Rwanda is located. This fact

abides in spite of the optimistic view that points to the stable political

environment and the availability of generous development aid of the order of

$50 per capita per annum coupled with the rewards of a significant debt relief

that was issued in 2005 (ibid). The fact that the threat of hunger and poverty

are far from over is not even waived by the bumper harvest of 2008 which fended

off the worst global food price crisis. Of course the

gRheaQPeQ.117Fia.113iQly17FRQhi A17A.1aRQg

17FRQhiF.1iRQ17iQ17i.1A17F13S13Fi.1v17.1R17.1a13QAIRaP 17.1Ke 17FRoQ.1ailA17

IRa.1oQeA. 17$ 17FlD13a17IRFoA 17RQ1713FFRPSUAKIQ1170 ' * 171

17iA1713a.11Fo113.1ed17iQ171.5 Z 13Qd13lA17( FRQRPiF 17 Development Poverty

Reduction Strategy (EDPRS) 2008 - 2012 and in its strategic Vision 2020, which

sets out the goal of advancing to middle income status by relying less on

unskilled agriculture but more on knowledge-based services such as tourism

(UNDP/HDRRwanda, 2007).

1

The Gini Coefficient measures how concentrated incomes are

among the population of an economy: the higher the Gini, the more

concentrated

incomes are among a few people. The Gini ranges between 0

(indicating income is distributed equally between all people) and 1 (indicating

all income in the economy accrues to one person).

The EDPRS results and policy matrix is organised around the 3

EDPRS flagship programs which have been aligned to the three clusters: The

economic cluster which covers the Macro Economic and Financial sector and

the economic sectors of Agriculture, Infrastructure (Energy, Transport),

Private Sector development as well as Environment and Natural Resources

management. The Social cluster covers Health, Education,

Social Protection, Water and Sanitation, and Youth; And Governance

cluster covers the following sector working groups: Public Financial

Management (PFM), Justice, Reconciliation, Law and Order (JRLO),

Decentralization, Citizen Participation, Empowerment, Transparency and

Accountability (DCPETA), and Capacity Building and Employment Promotion

(CBEP).

In spite of all this exuberant optimism by the Government,

most observers consider that the MDGs target of halving poverty by 2015 is very

unlikely to be achieved. There are signs that decentralization of government

structures has not progressed as quickly as hoped, and yet this is an important

factor in implementing poverty reduction programmes. On the other hand, the

government continues to depend on aid for no less than 49% of its 2010 budget

(ibid); and this leaves one wondering how far dependence on aid will take

Rwanda?s socio-economic development.

In 2004, the Government of Rwanda (GoR) was dependent upon

international development assistance to the tune of almost 50% of its overall

budget, and over 80% of its development budget. It was receiving over $350

million a year in aid from over 30 bilateral and multilateral donors and a wide

range of non-governmental organisations. (Hayman, 2006)

From a dependency theory point of view, this has an impact

particularly on the direction of development since the donors may pursue their

own socio-political agendas that may filter some ripple effects on the overall

economic growth within Rwanda. National policies and programmes aimed at

promoting economic growth, social welfare and political change were heavily

influenced by external actors: foreign technical assistants were bolstering

weak internal capacity within government institutions; policy consultants and

advisors were flying in and out of Rwanda?s capital city, Kigali, to help with

the preparation of policy papers and evaluations; a sizable community of

expatriate aid workers was present throughout the country. All this

necessitates the need to evaluate the far-reaching consequences of aid to

Rwanda. (Hayman, 2005).

In Kenya and Tanzania, the Swedish aid on rural development

had a positive impact in raising the standards of the poor. To this effect, it

would follow that socio-economic development within these nations was

registered. Radetzki in Word Bank (2005:258) maintains that in Tanzania,

Swedish has provided support for industrial forest planting and care,

sawmilling and related activities, technical assistance and village

afforestation and this began in mid 1969. One may argues that deforestation was

a major challenge which if not controlled could have costed the country to the

extent that it was going to be difficult to fight poverty. Poverty alleviation

is thus central in order to realise full socio-economic development at all

cost. Radetzki in Word Bank (2005:258) further posits that in Kenya soil

conservation was successful due to aid from Sweden. In this context, it would

follow that there is great need to conserve soil if sustainable agricultural

production that fight poverty is to be realised. Howell (2003:418) is of the

view that foreign aid from British to Agriculture in Kenya enhanced

agricultural research. To this effect, it follows that the impact of foreign

aid had positive impact on productivity.

Through research new conventional agricultural practices that

are geared towards effective fight against poverty are introduced. Johnston,

Hobenand Jaeger (2001:279) report that USA foreign aid support to sub-Saharan

Africa registered socio-economic development in that the economic aid has been

provided for primary development programmes, food aid, and budgetary support

under the Economic Support Fund (ESF) as «security supporting

assistance». One may observe that, such foreign aid was quite instrumental

in aiding to effective and sustainable socioeconomic development. In proposing

effective mechanisms for the provision of foreign aid, Lele and Jain (2001:579)

on their analysis of aid to African agriculture, argue that «donors should

ensure that their assistance programmes in individual countries successfully

combine a long term development strategy with the more pragmatic considerations

of day to day economic development. To this end, it follows that, such

strategies if intertwined with aid provision will effective anchor

socio-economic development of a given nation.

In narrating and tracing the impact of foreign aid and its

subsequent role in fighting poverty, Tsikata in Devarajan, Dollar and Holmgrain

(2001:47) maintain that «From a state of economic collapse, Ghana?s

economy rebounded with sustained economic growth during the first decade of the

reform. This stellar performance was accompanied by an exponentional increase

in aid inflows from both bilateral and multilateral sources. Against this

backdrop, it would follow that the introduction of foreign aid enhanced some

economic growth, thus socio-economic development is promoted. In a related

study, by Molmgrein (2001:101) of Uganda, it was noted that aid in various

forms helped to support the generation and implementation of the policy reforms

and Uganda. One may suggest that the various policy reforms may have some

bearing on the alleviation of poverty at all cost. In this context aid is

perceived to be part of development,

hence the need to have it as nations become geared for the

collective effort to fight the global poverty. Similarly, in Zambia, Parkner

(2001:1020) reports that aid was pivotal in promoting equitable socio-economic

development in the area of agriculture, infrastructure, health and education.

One may underscore the fact that if all these areas are funded it follows that

the impact of global poverty will be minimised at all cost. As Seers (1988),

would argue that development entails eradication of inequality, poverty and

unemployment. In advancing debates on the impact of aid to African countries,

Dambisa Moyo (2002) presents an argument that sometimes aid in Africa is not

working and proposed other mechanisms in order to remove or demystify the issue

of aid being classified as «Dead Aid».

To this end this brings us to the relativity nature of foreign

aid as put forward by the interactionist view that various subjective meanings

are attached to social phenomenon (Ritzer, 1996).

1.2 Statement of the Problem

Poverty has been regarded as a social problem that has

significantly affected a magnitude of people across cultures. To this end,

heated debates have been generated with regards the possible and viable ways of

eradicating the problem. However, foreign aid has been proposed as an ultimate

solution that can in turn propel the developmental proper shaft in the

socio-economic horizons. The problem has thus arisen in the legitimacy aspects

with regards the efficacy of foreign aid in enhancing, facilitating or

propelling as well as promoting socio-economic development particularly through

the eradication of extreme poverty and hunger to zero levels.

Rwanda has an increase in the depth of poverty in its several

areas and a deterioration of living conditions at the bottom of the income

distribution. As a consequence of rising inequality, Rwanda could have

exhausted its ability to reduce poverty rates through economic growth alone.

Growing inequality is not only an obstacle to poverty reduction and sustainable

economic growth; it could also undermine social peace. The problem would thus

be stated: Does foreign

aid have an impact in fighting SRY7TVIQ5EKuCI7TIEC5

FRCs7117CtlyESTRPRt7ISZEC5aVIRFIR-

economic development?

1.3 Research Questions

This study seeks to answer or address the following key research

questions:

1.3.1 What is the effect of poverty and hunger

on Rwanda?s socio-economic development?

1.3.2 Does foreign aid enhance Rwanda?s

socio-economic development?

1.3.3 Do citizens of Rwanda appreciate the

introduction of MDGs as guiding principles for poverty alleviation?

1.3.4 How effective are Rwanda?s strategic

policies on poverty reduction?

1.3.5 How sustainable is foreign-donor

assistance towards the reduction of

poverty and hunger; and how do the beneficiaries evaluate the

impact of such foreign aid on the local and national socio-economic

development?

1.4 Objectives of the Study

The study seeks to:

1.4.1 Assess the extent of poverty in Rwanda in

general and in Gasabo District in particular following the adoption of MDGs.

1.4.2 Examine the causal relationship between

foreign aid and Rwanda?s socioeconomic development.

1.4.3 Evaluate the effectiveness of Rwanda?s

poverty reduction policies and

strategies against its adoption of MDGs framework through foreign

aid. 1.4.4 Establish strategies for both donor community and

Rwanda for sustainable

development through poverty reduction.

1.5 Assumptions of the Study

The study is guided by the following assumptions:

1.5.1 Poverty and hunger has a number of effects

on Rwanda? socio economic development

1.5.2 Citizen of Rwanda appreciate MDGs at

different levels

1.5.3 Foreign aid might enhance Rwanda

socio-economic development

1.5.4 If effective policies and legislatives are

introduced to combat poverty,

Rwanda?s socio-economic development will be

attained

1.5.5 If foreign aid assists Rwanda in its

poverty program alleviation, there will be sustainable development.

1.5.6 The overall assumption is therefore

that: The Superpowers (US and its allies) and financial institutions give aid

with inhibiting conditional ties that still determine the nature of development

in LDCs such as Rwanda.

1.6 Significance and Justification of the Study

It is envisaged that this study will tend to immensely benefit

a cluster of beneficiaries among them the Government of Rwanda, Civil society,

the general citizens and other researchers. The Government of Rwanda (GoR) is

the intended primary beneficiary of the findings of this research. It is hoped

that the findings of the study will help put Rwanda into the driver?s seat

and help her devise its development programs and in leading coordination

processes. MINECOFIN (2004).

This research hopes to improve the relationship between Rwanda

and the donor community so that it becomes mutually beneficial rather than

lap-sided as is the case at present. The study shall also motivate and

stimulate other researchers hence they will have the intellectual vigour to

continuously advance scholarship into this seemingly grey area. In parallel to

this diversity amongst donors, the GoR itself responds in different ways to

individual donor agencies, in tune with its own perspectives of them and their

histories in Rwanda, and on the basis of its own strategic interests. This

research seeks to analyse these different perspectives on Rwanda in light of

the international consensus on aid effectiveness. It questions the diversity

amongst donors and the political factors on both the donor and recipient sides

which lie behind the aid relationship.

This study helps in identifying the explicit challenges that

Rwanda faces and strategies that could be designed for its socio-economic

development through Foreign Aid. In particular the research will sensitize the

citizens of Gasabo District to the negative or positive implications of donor

aid so that they deal with donor aid carefully.

This conscientization will help them avoid dependency

syndromes and to indigenize projects including those that are donor-funded. In

a sense they will own their development programs. On the whole, the study will

expose some of the shortcomings of the approaches being currently used by the

institutions such as United Nations Development Program (UNDP), United States

Agency for International Development (USAID), International Monetary Fund IMF,

World Bank (WB) among others to improve the Rwanda socio-economic development.

The general citizens of Rwanda will turn immensely benefit in that they will

have a deeper insight into causes and nature of hunger as well as getting an

enlightenment particularly after interacting with the key findings and

recommendation of this study.

Finally, the choice of the case study in this research is

deliberate - to examine the ultimate impact of foreign aid on the people of

Rwanda. It is both an exploratory and explanatory study which examines whether

or not foreign aid is a blessing or a curse. If it is a blessing, then how best

can it be further localized; if it is otherwise, then what home-grown solutions

can be given in place of foreign aid so that either way socio-economic

development can be realized?

In the final analysis although the results of this study are

confined to Gasabo (Rwanda), the insights into how donor aid can be used

sustainably can certainly be useful to all recipient countries in their

generality. The motivation of this study to the future researchers, it will

reanimate them in depth with the new approaches about the foreign aid and MDGs

in LDCs and will add more knowledge to the existing intellectual studies.

1.7 Definition of key terms

The following terms shall be understood the way they are defined

herein:

1.7.1 Socio-economic development

For the purposes of this study, socio-economic development

entails all development frameworks that may meet the social and economic needs

of the nation and its general citizens as well as assisting them to deal with

their current and future developmental challenges thus leading to attainment of

sustainable development at large.

1.7.2 Impact

For the purposes of this study, impact refers to the instrumental

role a given phenomena has on something be it positive or negative.

1.7.3 Foreign aid

For the purposes of this study, foreign aid shall be perceived

as eternal assistance in kind or cash that is rendered to a developing nation

by another country which can come directly or indirectly through donor

agencies.

1.7.4 Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)

For the purposes of this study, Millennium Development Goals

(MDGs) shall be perceived as quantitative developmental targets that were

adopted by different nations in pursuit of the World Bank (2002)

recommendations aimed at fighting the high prevalence of the so-called global

poverty.

1.7.5 Poverty

For the purposes of this study, poverty shall mean a state of

material and non-material deprivation which may be caused by socio-cultural,

economic or political factors.

1.8 Delimitation of the Study

In terms of peripheral guides, the study was confined to

Gasabo, a district (akarere) of Kigali City, Rwanda.

Its capital is Ndera, a village on the outskirts of the Kigali urban area. The

district also includes large areas of the city itself, including Kacyiru,

Kimihurura, Remera and Kimironko. The district occupies the northern half of

Kigali province, which had its boundaries extended under local government

re-organization in 2006 (MINALOC, 2006). Gasabo includes major suburbs of

Kigali, sections of a ring of hills which surround the city, and some villages

to the north and east of those. Rwanda's wealthiest area, Nyarutarama is also

in the district, as are the Offices of the President (in Kacyiru) and most of

the ministries.

Gasabo district is divided into 15 sectors

(imirenge): Bumbogo, Gatsata, Jali, Gikomero, Gisozi, Jabana,

Kinyinya, Ndera, Nduba, Rusororo, Rutunga, Kacyiru, Kimihurura, Kimironko and

Remera. As such, the results and findings obtained shall be perceived as

representative and generalisable too, to other districts not studied Donor

activities in all these areas will be explored. Both males and females

constituted the respondents in this particular study. The

study of aid in the context of hunger and poverty is broad. Conceptually, this

study is confined to the study of aid, poverty and development politics. It

entails defining foreign aid, poverty and development within the context of

MDGs. It entails exploring the complex dynamics and the politics of aid in

general and in the localized context of Gasabo, Rwanda.

It entails evaluating, competing perceptions of various actors

in the politics of aid and what may be said to constitute aid theory. The

timeframe in which the study is confined is 2000 to 2009. Spatially, the study

is limited to Gasabo District of Rwanda although literature will cover

Sub-Saharan Africa and beyond.

1.9 Limitations of the study

During the course of the study, the researcher experienced a

number of drawbacks which included lack of cooperation from respondents, time

inadequacy and financial constraints in meeting the budgetary requirements of

the study. However, efforts were made to address the constraints. The first

constraint was purely logistical. Given that the study was self-funded; the

researcher is faced serious challenges of financing travel to Rwanda for data

collection as well as financing the training of 10 assistant field

researchers.

The second major constraint was the methodological limitation.

Given that the study is based on a case study approach, it follows that it

inevitably exhibits the limitations of the method. Critics of the case study

believe that the study of a small number of cases can offer no grounds for

establishing reliability or generalizability of findings. This point is valid

when one considers that given the sensitive nature of the research some key

informants within the donor community and government offices may deny the

researcher access to important documents or information and this will lead to

information asymmetry. In light of this, others declined to be interviewed.

Thirdly, time factor was a limiting constraint. The fact that the researcher is

a mother, student and employee made it difficult for her to rationalise the

demands of these roles.

Also related to time was timing. The fact that the research

study took place against the background of genocide and genocide trials meant

that the subjects of research study were in different emotional states, so much

that they could easily provide or offer a political interpretation to the

study. In this case chances were that some sensitive members were not

forthcoming and forthright with their answers as expected. Such a background

threatened the validity of the outcome.

However, to overcome the above limitations there was need for

careful planning ahead of time. The planning should take into account use of

different data collection techniques such as direct observation, in-depth

interviews, questionnaires and focus group discussions in order to improve the

validity of data through methodological triangulation. Communication with

interviewees and questionnaire respondents should be done on time in order to

facilitate meetings. Besides, prior awareness of these limitations should

invoke constant sensitivity to their possibility so that due care is constantly

enforced.

1.10 Organisation of the Study

This study is structured into 5 main/key chapters. The first

one provides the introduction: background to the study, the problem statement,

objectives and the conceptual framework of the study. Chapter two presents a

detailed review of related literature: the main focus is putting into context

the polemics of aid theory in general, in Africa and in Rwanda-Gasabo. The

third chapter describes the methodology: the research design and instruments of

data collection to be used in the collection of data.

The findings of the research are then described, analysed and

collated in chapter four. Chapter five provides a summary of findings as well

as recommendations of the study.

1.11 Chapter summary

This chapter has provided the introduction of the study:

background to the study, the problem statement, objectives and the conceptual

framework of the study, the assumptions to the study, its significance,

delimitations and limitations, and the organisation of the study. The following

chapter is going to review related literature linked to the problem under

study. It shall give an overview of the current situation on Rwanda socio

economic development, policy and practice of both Rwanda and donor

community.

CHAPTER TWO: REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE

2.0 Introduction

This chapter offers a detailed review of related literature.

It will further trace the history of the problem against a background of

theoretical underpinnings. Ringrose (1986:78) notes that literature review

discusses published information in a particular subject area, and sometimes

information in a particular subject area within a certain time period. A

literature review can be just a simple summary of the sources, but it is

usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis.

The flow of foreign aid to Rwanda has been a subject of discussion especially

following the notorious genocide and its aftermath. To assess the impact of

foreign aid on the socio-economic development of Rwanda, there is need to

review some related literature.

This chapter deals with the conceptual framework of the study,

the theoretical framework, understanding poverty in the context of Millennium

Development Goal number one, impact of foreign aid on poverty alleviation

(global trends and trends in Africa in general and Rwanda in particular).

Finally, the chapter shall further offer implications of the reviewed

literature.

2.1 Theoretical Frameworks

Now that foreign aid, development and poverty have been

explained in broad terms, there is need to analyze some of the contending

theories on the nature of foreign aid. Four theories are hereby selected for

some detailed analysis. To this end, this study is principally informed by four

major theoretical frameworks namely the Modernization Theory, the Dependency

Theory, the

Interactionist Theory and the Feminist Theory. These

contending theories on aid provide various windows by which the impact of

foreign aid on poverty alleviation and economic development can be objectively

assessed.

2.1.1 The Modernization Theory and Foreign Aid

One of the first models used to understand how states and

regions started on the path to economic growth was Rostow?s Modernization

Theory. Analyses of European growth after World War II indicated a fairly rapid

and linear trajectory of economic growth that was built on a simplistic model

of saving and investment. According to Rostow?s analysis, modernization takes

place in a series of five stages characterized as follows:

The traditional society.

Preconditions for take-off into self-sustaining growth such

as increased education, manufacturing, and other forms of capital

development.

Take-off stage occurs when the economic norms become

established at micro, mezzo and macro levels, which lead to

A drive to maturity characterized by economic diversification

and increased standards of living.

The final stage is characterized by mass consumption, which

drives continued production, technological development, and job growth.

(Todaro: 2006: 104)

These stages imply that the rate of growth of GDP is determined

jointly by the national savings

ratio and the national capital ratio. More

specifically, it says that in the absence of government

control, the growth

rate of national income will be directly related to the savings ratio (ibid).

The

economic logic of this paradigm is simple: in order to grow,

economies must religiously follow the stages; and to achieve the imperatives of

each stage, they must concentrate on savings and local and direct foreign

investment. Rostow assumed the validity of the primary economic model of growth

at the time, the Harrod-Domar growth model (ibid), which was the basis for the

savings + investment = growth formula. While intuitively attractive (to the

capitalist worldview) and empirically supported at the time, it assumed a

linear growth based on the two isolated variables of savings and investment.

While such a trend seemed to be the case in Europe after the world wars,

Europe?s advantage over other regions (such as Southeast Asia and Africa), is

that it already had a pre-existing infrastructure, and a population already

educated in the skills and norms necessary for technologized life. Among other

factors, it ignores hegemonic consequences of having military, political and

economic power at a state/region?s disposal to procure capital external to

itself.

This theory assumes that the «Third World» needs

Western donation in order to advance. Indeed, one may observe that the

discourse of foreign aid is rooted in the Modernization Theory. Modernization

theory understands the «underdeveloped» nations of the world as

traditional societies. At some point in history all societies were

«traditional.» These societies were able to progress to modern social

organization through innovation and technological growth, particularly within a

capitalist system where capital is privately owned. Capitalism encourages the

individual to constantly strive toward improving her product. Growth is

promoted by this push for out-performance, while costs are minimized and

efficiency promoted. Therefore, just as modernization and capitalism push a

nation to modernity, the poverty of the developing nations can be attributed to

their failure to innovate, resulting in technological and therefore economic

deficit, and a consequent inability to modernize. Foreign aid,

understood as a means to improve the conditions of life in underdeveloped

nations, is couched within modernist thought. It is the practical expression of

the theoretical premise that modernized nations are morally obligated to assist

other nations to transition to modernization Todaro (1981). To this effect, the

modernisation theorists would support the idea that third world nations should

always look west in order to develop through coping western models of

development. Foreign aid may thus be perceived as a rescue package for an

affected nation to be freed from hunger and poverty.

This brings us to the major criticisms levelled against the

Modernization Theory mainly by Dependency theorists who include Marxists.

2.1.2 The Dependency Theory and Foreign Aid

The debates among the liberal reformers, the Marxists, and the

world systems theorists have been vigorous and intellectually challenging over

the years. There are still points of serious disagreements among the various

planes of dependency theorists and it is a mistake to think that there is only

one unified theory of dependency. Nonetheless, there are some core propositions

which seem to underlie the analyses of most dependency theorists. Dependency

can be defined as an explanation of the economic development of a state in

terms of the external influences -- political, economic, and cultural-- on

national development policies (Osvaldo Sunkel: 1969: 23). Theotonio Dos Santos

(1971:226) emphasizes the historical dimension of the dependency relationships

in his definition:

[Dependency is]...an historical condition which shapes a

certain structure of the world economy such that it favours some countries to

the detriment of others and limits the development possibilities of the

subordinate economics...a situation in which the economy of a certain group of

countries is conditioned by the development and expansion of another economy,

to which their own is subjected.

There are three common features to these definitions which

most dependency theorists share. First, dependency characterizes the

international system as comprised of two sets of states, variously described as

dominant/dependent, center/periphery or metropolitan/satellite. The dominant

states are the advanced industrial nations in the Organization of Economic

Cooperation and Development (OECD). The dependent states are those states of

Latin America, Asia, and Africa which have low per capita GNPs and

which rely heavily on the export of a single commodity for foreign exchange

earnings. Susanne Bodenheimer (1971). Second, both definitions have in common

the assumption that external forces are of singular importance to the economic

activities within the dependent states. These external forces include

multinational corporations, international commodity markets, foreign

assistance, communications, and any other means by which the advanced

industrialized countries can represent their economic interests abroad.

Third, the definitions of dependency all indicate that the

relations between dominant and dependent states are dynamic because the

interactions between the two sets of states tend to not only reinforce but also

intensify the unequal patterns. Moreover, dependency is a very deep-seated

historical process, rooted in the internationalization of capitalism. In short,

dependency theory attempts to explain the present underdeveloped state of many

nations in the world by

examining the patterns of interactions among nations and by

arguing that inequality among nations is an intrinsic part of those

interactions (ibid). Most dependency theorists regard international capitalism

as the motive force behind dependency relationships. Andre Gunder Frank (1972:

3), one of the earliest dependency theorists, is quite clear on this point:

....historical research demonstrates that contemporary

underdevelopment is in large part the historical product of past and continuing

economic and other relations between the satellite underdeveloped and the now

developed metropolitan countries. Furthermore, these relations are an essential

part of the capitalist system on a world scale as a whole.

According to this view, the capitalist system has enforced a

rigid international division of labour which is responsible for the

underdevelopment of many areas of the world. The dependent states supply cheap

minerals, agricultural commodities, and cheap labour, and also serve as the

repositories of surplus capital, obsolescent technologies, and manufactured

goods. These functions orient the economies of the dependent states toward the

outside: money, goods, and services do flow into dependent states, but the

allocation of these resources is determined by the economic interests of the

dominant states, and not by the economic interests of the dependent state. But

before going into the debate on whether aid does encourage dependency and

inefficiency, we need to address a particular misconception: that aid to

developing countries, known as official development assistance (ODA), is an act

of simple generosity towards poor countries in dire need of capital to invest

in education, health, infrastructure, and so forth, and that it comes with no

strings attached. Development assistance is neither value-free nor benevolent.

It has served and continues to serve the economic, political and strategic

interests of

donor countries. This was particularly so during the Cold War

period. It is even more evident today. (ActionAid, 2005)

So aid is an instrument, not a gift. For many Western

countries and institutions, it plays a key role in their overall strategy to

maintain and even expand their influence in Africa. This is particularly true

for former colonial powers such as France and Britain, which have used aid to

maintain their influence in former colonies, in economic, financial, military

and strategic areas. This type of aid does create dependency and it is intended

to, since its primary objective is to shore up regimes that are

friendly? to Western countries, regardless of the nature of those

regimes. This explains, among other things, why a dictatorial and inept regime

like Mobutu in the former Zaire (DRC) was kept afloat despite the looting of

his country?s resources and the rampant corruption that characterized his

regime. Billions of dollars looted by Mobutu are still stashed in Western banks

while the Congolese people wallow in poverty (ibid).

Moreover, since the start of the debt crisis, aid dependency

has been aggravated by conditions imposed by the IMF and World Bank. Since the

1980s, aid from Western countries has been conditional on recipient countries

implementing policies dictated by these two institutions. One may argue that, a

typical example is the catastrophic ESAP of Zimbabwe in the 1990s. Even aid

from former colonial powers to their former colonies is now conditional on

signing an agreement with the IMF, yet it has become clear that these policies

have done more harm than good. (Government of Zimbabwe 1991)

The dependency on foreign aid has political as well as

economic costs. It is obvious that a country that depends on foreign assistance

for up to 40 per cent of its budget cannot control its own policies. Instead,

as the IMF and World Bank?s structural adjustment programmes show, donors

dictate economic and financial policies, based on their own world view and

interests (HDR-UNDP, 2007). The structural adjustment programmes, imposed by

the IMF and World Bank, are a reflection of that reality. As already indicated

this has worsened the economic crisis and deepened external dependency, while

the conditions attached to such multilateral aid are the principal cause of the

abject poverty affecting more than half of the African population. Against this

background, one may argue that from a dependency theory point of view, the

issue of foreign aid is a form of colonialism (neo-colonialism),hence Third

world nations will remain entirely dependent on first world nations.

On the whole the Modernization and Dependency theories are

macro-theories that evaluate society from a holistic perspective. As such there

is no wonder why all of them fail the test of local contextualization; hence

the need to look at some micro - theories that can explain the politics of aid

at a micro or local level. Two theories have been selected for this balancing

purpose: interactionnism and feminism.

2.1.3 Interactionism and Foreign Aid

Symbolic interactionism is a major sociological perspective

that places emphasis on micro-scale social interaction. Symbolic interactionism

is derived from especially the work of George Herbert Mead. The basic

assumption of interactionism is that people act toward things based on the

meaning those things have for them; and these meanings are derived from social

interaction and modified through interpretation. In other words human beings

are best understood in relation

to their environment. Herbert Blumer (1969) who coined the term

"symbolic interactionism," set out three basic premises of the perspective:

Humans act toward things on the basis of the meanings they

ascribe to those things.

The meaning of such things is derived from, or arises out of, the

social interaction that one has with others and the society.

These meanings are handled in, and modified through, an

interpretative process used by the person in dealing with the things he/she

encounters.

Blumer, following Mead, claimed that people interact with each

other by interpreting or defining each other's actions instead of merely

reacting to each other's actions. Their response is not made directly to the

actions of one another but instead is based on the meaning which they attach to

such actions. Thus, human interaction is mediated by the use of symbols and

signification, by interpretation, or by ascertaining the meaning of one

another's actions. (Blumer 1962). From this analysis of interactionism one can

note that the Interactionist interpretation of foreign aid depends entirely on

the perceptions of the actors in the aid continuum. These include the donor,

the boundary partners in the middle and the recipient at the end of the

continuum. It goes without saying that the donor knows why he is donating in

the first place; but the point that needs emphasis is that the public can only

be made to know what the donor makes public that is, the donor?s explicit

motives. However, if the donor has hidden agendas, such agendas can only be

guessed by the public, otherwise the ulterior motive remains hidden from the

public sphere and the donor is not likely to disavow his hidden agenda in any

public forum. Nonetheless, even that hidden agenda remains intrinsically part

of the donor?s definition of the aid he releases.

On the other hand, the boundary partners, because they benefit

from the aid process, are likely to accept the donors? definition of aid. They

are most likely to resist any temptation to see aid in any other light than

prescribed by the donor. However, the recipients of aid are likely to interpret

aid differently depending on their varied needs. Those in extreme need may see

aid as none other than benevolent. They hardly see any dangers of dependency

but simply accept the donor as the saviour. On the other hand, those especially

educated recipients who may not be in dire need of such aid or whose political

portfolios are threatened by their subjects? allegiance to new saviours are

likely to treat aid with suspicion. The local intellectuals may take the

suspicion further to attaching such aid with ulterior motives. The point that

needs emphasis, though, is that foreign aid is interpreted differently by

different actors owing to different needs and sensibilities.

2.1.4 Feminism and Foreign Aid

Unlike interactionism, Feminism offers an explanation of how

economic models, policies and budget frameworks and processes have not adopted

a gender perspective, and how this has caused women to bear the brunt of

poverty. The theory deplores that economic models, policies and budgetary

frameworks that are adopted by different African governments and institutions

often ignore the lived realities of women; but that men largely dominate and

control not only the means of production but also economic decision-making.

Most nations in Sub-Saharan Africa have dual economies that consist of both

formal and informal sectors. Men are dominant in the formal sector, while women

dominate the informal and communal sectors. There is a discernible trend in

Sub-Saharan Africa that economic and development policies target the formal

sector, marginalising the informal and communal sector where women mostly

participate.

The Millennium Declaration, signed in September 2000 at the

United Nations? Millennium Summit, commits the member countries «to

promote gender equality and the empowerment of women, as effective ways to

combat poverty, hunger and disease and to stimulate development that is truly

sustainable. (UN, 2000). Accordingly, the greater part of women?s contribution

to the economy is not counted and not truly reflected in national accounts.

Similarly, women?s role in influencing and participating in economic policy

formulation is side lined, leaving them to deal with the impacts of poverty and

marginalisation. (Lucy Makaza-Mazingi, 2009).

The feminisation of poverty is a phenomenon where poverty is

viewed as disproportionately

affecting and impacting on women more than it does on men. The

phenomenon has been linked, firstly, to a perceived increase in the proportion

of female-headed households (FHHs) and, secondly, to a rise of female

participation in low returns urban informal sector activities, particularly in

the context of the 1980s? economic crises and adjustments in sub-Saharan Africa

and some Asian countries. The feminisation of poverty can be viewed from three

distinct standpoints namely (ibid):

|

That women have a higher incidence of poverty than men;

That their poverty is more severe than that of men;

That there is a trend of greater poverty among women particularly

associated with rising

rates of life.

|

This raises questions as to whether Southern Africa can meet

the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) number one: of reducing poverty by half

by 2015. In Zimbabwe, the Poverty Assessment Study Survey-PASS II (2003),

revealed that poverty remains higher among female-headed households than male

headed households. The Botswana women?s NGO forum notes that 55

percent of the population in rural areas in the country earns

income below the poverty line and female-headed households make up 41 percent

of those living in poverty as opposed to 34 percent for male-headed households.

A survey carried out in Zambia revealed that 50 percent of female-headed

households were classified as very poor compared to only 27 percent of the

male-headed households (ANSA, 2006).

A noticeable trend in Southern Africa is the dominance of men

in most of the occupations associated with high responsibility, job security,

dignity, high earning and social status, while women are relegated to the

low-paying jobs thus increasing inequality between women and men. In addition,

the African Development Bank?s (ADB) (2008) Gender Policy notes that

feminisation of poverty is directly related to the absence of economic

opportunities, the lack of access to economic resources (including credit, land

ownership and inheritance), and the lack of access to education and support

services.

Despite the signing of the 1995 Beijing Declaration, the

action plan on women?s empowerment, and the many declarations and debates on

gender equity in Africa, the women in Southern Africa still reflect the ugly

face of poverty statistics. The recently adopted SADC gender protocol

recognises the feminisation of poverty as one of the threats to the fragile

gains made towards gender equality over the past decade in the areas of law

reform, representation in politics and decision-making, and some strides in

education, with certain African countries reportedly achieving some of the MDGs

on gender- related issues. The traditional discipline of economics, which still

to a large extent implicitly informs the current economic modelling and

discourse in Southern Africa, has relied on a number of critical assumptions

about women and their roles (ibid).

There is now a shared understanding within the development

community that development policies and actions that fail to take gender

inequality into account and fail to address disparities between males and

females will have limited effectiveness and serious cost implications. For

example, a recent study estimates that a country failing to meet the gender

educational target would suffer a deficit in per capita income of 0.1-0.3

percentage points. (Dina Abu-Ghaida and Stephan Klasen, 2002). One may observe

that, by the same token the distribution of foreign aid has been heavily skewed

in favour of men over the years mainly because most donor organisations are

controlled by men who happen to occupy higher positions within these

organizations.

One may argue that to date, women are not considered a human

factor in decisions on aid for economic and social development; hence women and

children remain victims of the poverty trap. Todaro, (1993) is of the view that

development is a multi-dimensional concept which can be realized through

promoting gender equity. Burvic and Gupta, (1994) note that «where women

are targeted with resources it is often assumed that benefits accrue directly

to them and also to their children, to a greater extent than resources targeted

at men.

2.2 Conceptualizing aid, development, poverty and

hunger

Aid is simply the transfer of money, goods and technical

assistance from a donor to a recipient. According to Todaro, [1981], foreign

aid is any official development assistance or "any flow of capital to least

developing countries...» and its objective should be characterized by

"concessional» terms, that is, the interest rate and repayment period for

borrowed capital should be "softer" [less stringent] than commercial terms".

One may observe that, Todaro?s conceptualization of aid in this case takes for

granted that the impact of any such aid is

development; but unfortunately it misses the point that

development is relative. On one dimension, development depends on the

perspective of the beholder; in which case the donor, the recipient of aid and

the independent observer all judge the impact of aid from different angles and

with different sensibilities. Against this background, the Government of Rwanda

and its Development Partners have put in place a number of inter-linked forums

for dialogue on aid coordination at different levels. At the 2006 Government of

Rwanda and Development Partners Meeting, Rwanda?s donors presented a joint

statement of their intent with respect to the implementation of Rwanda?s Aid

Policy and the Paris Declaration. As part of this, donors agreed to adopt the

2010 targets above as individual targets, recognizing that collective

achievements against the Paris targets rely on the efforts of individual

partners. Central to in-country dialogue around aid effectiveness are a number

of key forums that bring together government, donors, civil society and the

private sector at a number of levels:

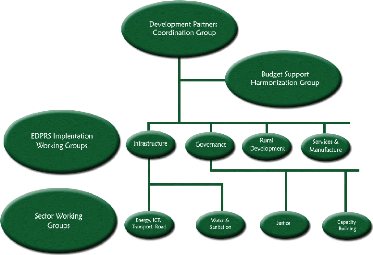

Figure 2.1: Aid Coordination Architecture in

Rwanda

Source: MINECOFIN, 2007

On another angle one may argue that the concept of aid may be

best understood from a historical perspective. During colonialism, European

colonial powers were concerned with the economic development of the territories

they occupied, hence they often released economic assistance to their proxy

governments in the occupied territories. Whether the beneficiaries of the

assistance were the minority ruling white elite or the majority ruled Africans

was not an issue for serious auditing by aiding cosmopolitan governments.

Mikesell (1983: 1) posits that even after independence «much of their

economic assistance to the new independent states formed after World War II

constituted a continuation of their development and other economic assistance

during the colonial period».

On the other hand, the World Bank charter of 1944 argues that

the Developed Countries had a dual function of promoting the reconstruction of

the war-torn countries, developed and developing, and of promoting economic

development in the less developed countries (ibid). The concept of development

assistance as enshrined in the Articles of Agreement for the World Bank aims at

promoting the flow of private international capital in the form of both loans

and direct investment investments to developing countries (Mikesell 1983). To

this end, from a Utopian perspective, Aid would best be defined as loan, grant