|

THE PEOPLE'S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ALGERIA

MINISTRY OF HIGHER EDUCATION

AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH

UNIVERSITY OF COLONNEL EL HADJ LAKHDAR, BATNA

FACULTY OF LETTERS AND HUMAN SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF

ENGLISH

LINGUISTIC AND CULTURAL

KNOWLEDGE AS PREREQUISITES

TO LEARNING PROFESSIONAL

WRITTEN TRANSLATION

THE CASE OF FIRST AND THIRD YEAR

TRANSLATION

STUDENTS AT BATNA UNIVERSITY

A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PART REQUIREMENT FOR A DEGREE

OF

MAGISTER IN FOREIGN LANGUAGE TEACHING

|

Presented by:

Mrs. Fedoua MANSOURI

Jury Members:

1. Chairman: Dr. Omar GHOUAR

2. External Examiner: Dr. Nabil

MENNANI

|

Supervised by: Pr. Med Salah NEDJAI

|

70 DfE MEMORT

09

MY FAD[ER

I would like to express my deep gratitude to:

My supervisor, Pr. M. S. NEDJAI, to whom I owe every forward step

of my way.

My husband, my mother and brothers, whose support was beyond all

my expectations.

My friends, whose kind words and deeds were of valuable help to

me.

- The staff of the Translation Department of Batna University,

for their constant assistance and encouragement.

70 DfE MEMORT

09

MY FAD[ER

I would like to express my deep gratitude to:

My supervisor, Pr. M. S. NEDJAI, to whom I owe every forward

step of my way.

My husband, my mother and brothers, whose support was beyond all

my expectations.

My friends, whose kind words and deeds were of valuable help to

me.

- The staff of the Translation Department of Batna University,

for their constant assistance and encouragement.

iv

List of Figures

Figurel: The ex post fact

design 98

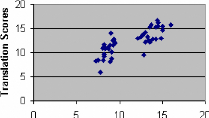

Figure 2 : Correlation Between Language

Scores

and Translation Scores 114

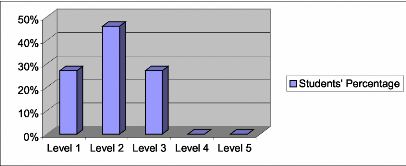

Figure 3: Distribution of Observed

English Competence Levels 130

Figure 4 : Distribution of Observed

Arabic Competence Levels 134

Figure 5: Overall Students' Performance

on the English General

Culture Test 135

Figure 6: Overall

Students' Performance on the Arabic General

Culture Test 138

Figure 7: Distribution of Arabic-English

Translations Levels 150

Figure 8: Distribution of English-Arabic

Translations Levels 157

V

List of Tables

Table 1: Gender proportions in the ex post

facto sample 100

Table 2: Means, Standard Deviations and

T-values 108

Table 3: Summary of the Correlational

Analysis 113

Table 4: Distribution of Observed English

Competence Levels 129

Table 5: Distribution of Observed

Arabic Competence Levels 133 Table 6: Classification

and Quantification of English Culture Answers 134 Table 7:

Classification and Quantification of Arabic Culture Answers 137

Table 8: Description of Arabic-English Translations levels 143

Table 9: Examples of Level One Translations of Some

Arabic Source Text Items 144

Table 10: Examples of Level Two

Translations of Some Arabic

Source Text Items 146

Table 11:

Examples of Linguistic Errors Found in Level Two

Arabic-English Translations 147

Table 12: Examples of Level Three

Translations of Some

Arabic Source Text Items 148

vi

Table 13 : Examples of Linguistic Errors

Found in Level

Three Arabic-English Translations 149

Table 14: Examples of Level Three

Adequate Translations

to Some Arabic ST Items 149

Table 15: Distribution of Arabic-English

Translations Levels 150

Table 16: Description of Arabic-English

Translation Levels 152

Table 17: Examples of Linguistic Errors

Found in Level One

English-Arabic Translations 153

Table 18: Examples of Meaning Transfer

Inaccuracies in Level Two English-Arabic Translations 154

Table

19: Examples of Level Three Inappropriate Translations

of Some Source Text Items 155

Table 20: Distribution of English-Arabic

Translations Levels 157

CONTENTS

Dedication i

Acknowledgements ii

Abstract iii

List of Figures iv

List of Tables v

Contents vii

INTRODUCTION

General Background 1

Research Questions 2

Hypotheses 3

Objectives 4

Scope of the Study 6

Limitations of the Study 7

Significance of the Study 8

Basic Assumptions 9

Terms Definition 10

Chapter One

LITERATURE REVIEW

Introduction 12

1.1. Linguistic and Cultural Knowledge

13

1.1.1. Translation and Language 13

1.1.1.1. Difference between languages 14

1.1. 2. The Translator's Linguistic Knowledge

18

1.1.2.1. Knowledge of the native language 20

1.1.2.2. Knowledge of the foreign language

22

1.1.2.3. Textual knowledge 23

1.1.2.4. Communicative competence 25

1.1.2.5. Controlled linguistic knowledge 26

1.1.3. Translation and Culture 27

1.1.4. The Translator's Cultural Knowledge

32

1.1.5. Learning Culture 35

1.2. Translation Competence 37

1.2.1. The Term "Translation Competence" 37

1.2.2. Translation Competence Versus Linguistic

Competence 39 1.2.3. Nature of Translation Competence

40 1.2.4. Translation Competence Acquisition and

Language Learning 49

1.3. Some Aspects of the Activity of

Translation 53

1.3.1. Translation Problems 53

1.3.1.1. Translatability 53

1.3.1.2. Peeter Torop's Scheme of Culture

Translatability 56

1.3.2. Translation as Decision Making 63

ix

1.3.3. Some Aspects of the Translator's Responsibility

67

1.4. An Account for Admission ReQuirements in Some

Foreign Translation Schools 72

1.4.1. Institut de Traduction at Montreal

University in 1967 73

1.4.2. L'Université du Québec en

Outaouais in 2004 74

1.4.3. Ecole Supérieure d'Interprètes

et de Traducteurs at Paris

l'Université Paris III in 2004

76

1.4.4. Views of SomeTranslation Scholars and

Teachers 78

1. 5. Measuring Translation Learning

Progress 81

1.5.1. Campbell's Developmental Scheme 85

1.5.2. Orozco and Hurtado Albir's Model 87

1.5.3. Waddington's Experiment 90

Conclusion 92

Chapter Two

METHODOLOGY DESIGN

Introduction 94

2.1. The Ex Post Facto Study 94

2.1.1. Research Questions 94

2.1.2. Operational Definitions of Variables

95

2.1.3. Choice of Method 96

2.1.4. The Ex Post Facto Design 98

2.1.5. Sampling 99

2.1.6. Data Collection Procedures 101

2.1.7. Statistical Analysis 102

2.1.7.1. Means Comparison 103

2.1.7.2. Correlation 109

2.2. The Qualitative Study 115

2.2.1. Research Questions 115

2.2.2. First Year Students' Knowledge 116

2.2.2.1. Objectives 116

2.2.2.2. Research Questions 116

2.2.2.3. Sampling 117

2.2.2.4. Data Gathering Procedures 118

2.2.2.4.1. English language test 118

2.2.2.4.2. Arabic language test 120

2.2.2.4.3. English and Arabic general culture tests 121

2.2.2.5. Data Analysis and Evaluation 124

2.2.2.5.1. English language test 124

- Qualitative description 124

- Quantitative description 129

2.2.2.5.2. Arabic language test 130

- Qualitative description 133

- Quantitative description 133

2.2.2.5.3. General culture tests 134

2.2.2.5.3.1. English culture test 134

- Quantitative description 134

- Qualitative description 135

2.2.2.5.3.2. Arabic culture test 137

- Quantitative description 137

- Qualitative description 138

2.2.3. Third Year Translations' Evaluation

140

2.2.3.1. Objectives 140

xi

2.2.3.2. Research Questions 140

2.2.3.3. Sampling 141

2.2.3.4. Tests Materials and Administration

141

2.2.3.5. Translations' Evaluation 142

2.2.3.5.1. Arabic-English translations' evaluation 143

- Qualitative description 143

- Quantitative description 150

2.2.3.5.2. English-Arabic translations' evaluation 151

- Qualitative description 151

- Quantitative description 157

2.2.4. Results' Summary 158

2.2.4.1. First Year Students' Knowledge 158

2.2.4.1.1. Linguistic Competence 158

2.2.4.1.2. General Culture 159

2.2.4.2. Third Year Students' Translation Competence

160

2.2.4.2.1. Arabic-English 160

2.2.4.2.2. English-Arabic 161

Conclusion 161

Chapter Three

DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

3.1. Results' Discussion and Interpretation

162

3.2. Recommendations 170

General Conclusion 172

Bibliography 175

Appendices 187

INTRODUCTION

The translator's responsibility is multidimensional. Indeed,

it decides on professional, pragmatic and cultural issues, to mention but a

few. It is thus quite natural that Translator Training be no less crucial a

responsibility. At the moment a student translator ends his four-year course,

he is considered to be ready to practice professional translating, that is to

start taking over the profession's charges. This suggests that at the end of

the course he would be deemed to possess the required knowledge and competence

for a beginner professional translator. This could be attained only through

efficient knowledge and competence acquisition. Furthermore, the extent to

which a beginner professional might develop and progress towards becoming a

good translator is significantly determined by the knowledge and competence he

possesses as a beginner.

Acquiring the required knowledge and competence is,

nevertheless, not as simple as it may be assumed. The great amount of knowledge

to be learnt and the specific type of skills to be developed in a relatively

short period of time explain this belief (Pym, 2002). The learning process of a

would-be translator is, thus, quite intense and complex.

However, some may judge this statement too demanding. Indeed,

it is generally believed that learning translation involves no more than the

acquisition of one or two foreign languages. This belief might be felt, it

should be noted, even among some well-educated people. Although this is not

necessarily the way Translation students at Batna University themselves think,

it is hard to assert that they are fully ready to meet all the requirements.

We have noticed that students enter the Translation course

with very little linguistic and cultural knowledge, especially as far as

foreign languages are concerned. Logically, this low level calls for more

adapted programs. Language programs, in particular, are reduced to elementary

lessons aiming to provide students with the basic linguistic knowledge they

lack (Nord, 2000; Gouadec, 2000; Gambier, 2000). As this aim is likely to take

a long time to achieve, considerable amount of time and effort would inevitably

shift to language learning objectives on the detriment of the initial

objectives of the course. We assume that these objectives are Translation

Competence acquisition and linguistic and cultural knowledge perfection.

Research Questions

Many questions rise, justifying the need to conduct the present

study. These questions are the following:

· Do prior linguistic competence and cultural knowledge

make any difference in what a student acquires, in terms of translation

competence, in a given period of time? Or,

o does this knowledge determine the quality and the pace of the

translation student's subsequent learning process?

· Are prior linguistic competence and cultural knowledge

prerequisites to learning translation? Or,

o Is it possible to learn languages, their cultures and

translation from and into these languages simultaneously?

· Regarding these questions, what is the present state of

translator training in the Translation Department of Batna University? In other

words:

· How is the performance of the Translation Department

of Batna University under the established students' selection system?

Particularly:

· How is the traditionally selected students' knowledge

at the beginning of the course? And what do they learn within two or three

years of study? More specifically,

o What is the current level of newly selected students' prior

linguistic knowledge and general culture in the Translation Department of Batna

University?

o What is the current level of third year students'

translation

competence in the Translation Department of Batna University?

Hypotheses

This work aims at testing the following main hypotheses:

· Sound prior linguistic and cultural knowledge prepare

the student for the translation course. Hence, they bring him learn translation

better and faster.

· Without this prior knowledge there is no effective

translation learning.

· Hence, this prior knowledge is a prerequisite for

translation learning process to attain the course objectives.

· Criteria currently used in Batna Translation Department

for selecting translation students are not sufficient.

Objectives

To test our hypotheses, a study comprising a quantitative and

a qualitative part has been conducted in the Translation Department at Batna

University. Subjects are first and third year students of translation. The

quantitative study attempts to check whether prior linguistic and cultural

knowledge make any difference in subsequent translation learning success. It

compares the prior knowledge of two different groups

of third year students, selected on the basis of "translation

competence" criterion. In other words, one group is believed to have more

translation competence than the other.

The qualitative study's aim is to test the hypotheses through

the description of the present state of affairs. Indeed, it attempts to examine

the established system's effectiveness, as far as students' selection is

concerned. This system gives the priority to students from literary streams,

and is based on Baccalaureate general mean and foreign languages grades (see

Appendix A).

It addresses two issues. Firstly, it looks at the value of the

Baccalaureate degree in terms of linguistic competence and general culture.

This evaluation does not concern the Baccalaureate degree as such, but as a

unique selection criterion. Hence, it evaluates the overall knowledge standard

of first year translation students before they start the course. This

evaluation involves linguistic competence in Arabic and English, and general

culture. Testing general culture aims to improve our understanding of the

general knowledge traits of present-day freshmen.

Secondly, the qualitative study attempts an evaluation of

third year students' translation competence. This is to see what students with

no more than Baccalaureate level could learn within three years.

Scope of the Study

First, this study limits itself to written translation. The

oral one entails different factors to be investigated, like listening and

speaking skills. These are not similar to those written translation

requires.

Secondly, we would like to point out that the qualitative part

of this paper does not aim at providing an accurate evaluation of individual

competence or knowledge. Its goal is rather to look for signs indicating the

general knowledge standard.

Thirdly, it should be mentioned that linguistic competence and

cultural knowledge are only two aptitudes among many others worth investigating

in the same framework. This study does not imply that they are the only

prerequisites. Nor does it intend to consider all the abilities a candidate to

a translation course needs or needs not possess. Cognitive abilities and

affective dispositions are some examples. It is true that some literature

(Alves ; Vila Real & Rothe-Neves, 2001) as well as foreign translation

schools advocate their necessity as a prerequisite. However, they lie beyond

the scope of this research. If, in our literature review, some hints are

present, it is for the sake of emphasising the value and the complexity of

translator training.

Finally, this paper is not expected to provide a precise

description of the type and amount of knowledge it is deemed necessary to

possess.

This issue might be proposed as further research to be conducted

in the field.

Limitations of the Study

We remain aware of the multitude of extraneous variables

likely to alter the effect of previous knowledge on the learning process.

Experimental manipulation and randomisation are lacking in the design we have

chosen. Consequently, students' motivation, social situation, economic status,

physical condition, sex, and interaction may influence their learning. They

might influence also their performance at the exams or the tests constituting

this study's source of data.

Nevertheless, it should be noted that if these variables might

affect the results of the study, they would similarly affect the student's

performance in real life conditions. This does not bring foreign translation

schools to stop selecting their students on the basis of previous knowledge

criteria.

Furthermore, the present study is not an experiment in which

variables must be isolated, controlled and manipulated. It is a descriptive

study, which implies dealing with real and authentic rather than laboratory

settings. Hopefully, the fact of the absence of artificiality in our research

proceedings might add to the findings' credibility.

Besides, some factors like motivation might be in their turn

positively influenced by prior knowledge. Hence, it would be an integral part

of the relationship we propose to investigate. It follows that controlling such

a variable would be both hard and pointless.

Anyway, efforts that have been made to account for some

extraneous variables will be explained within the procedures' sections.

Significance of the Study

Obviously, the study's findings will lead to recommendations

as to what is needed for positive change to occur. It is hoped that our

recommendations would serve to improve the academic level of the Translation

Department of Batna University and help in training qualified translators.

The study's findings are also expected to provide insight into

central issues to translation and Translation Studies. More specifically, we

hope to increase awareness concerning some common misconceptions like the

confusion between learning translation and learning languages.

The need to conduct this research is strongly justified, also,

by the lack of research conducted in the field in Algeria (Aïssani, 2000).

Aïssani (2000) states that Algerian graduates in translation turn to

neighbouring disciplines, like linguistics, to carry out a research work.

Besides, when

research is performed in the field, it is generally under the

form of books' translations. Very little work addressed Translator Training

issues.

Ideally, this study could also be considered as a contribution

to the literature submitting one of Translator Training aspects to empirical

study. Moreover, it is hoped that implementing translation evaluation

instruments, as a research tool, will constitute a first step towards further

exploration of this specific issue in Batna University, at least.

As small size samples, namely no more than 10 subjects, represent

one of the weaknesses of available field research (Orozco and Hurtado Albir,

2001), it is assumed that the relatively large samples under investigation will

add more scientific value to the present research.

We would like our work to remain within the expectations of a

scientific rationale and the principle of originality: two main reasons to

account for the choice of our subject and our methodology.

Basic Assumptions

We assume that culture, in its anthropological definition (see

p. 28), is not systematically taught and tested in Algerian pre-university

language class. This is clear when we examine Algerian Baccalaureate Exams of

the English language. We would find no testing of any cultural knowledge, which

implies that teaching it was not a fundamental component of the curriculum.

As will be exposed in the literature review, Chastain (1976)

advances that, in order to test it, culture should be taught and tested

systematically (p. 509). Therefore, it was not possible for this study to test

this kind of knowledge. Any testing of a randomly acquired knowledge would be

subjective. And as this testing was meant for statistical analysis, we settled

for considering the kind of culture that is actually and systematically taught.

It is culture that includes history, geography and philosophy. The aim

was, as mentioned earlier, to see whether or not it had an effect on learning

translation.

We maintain, however, that knowledge of the language's culture

is a very important component in a good linguistic competence. Throughout the

literature review, this claim is being supported.

Definition of Terms

Culture: throughout this study, this

controversial concept has been attributed more than one definition. Each time

the relevant definition will be determined. Here is a broad description of each

context's definition:

- As far as the literature review is concerned, it is used to

mean "lifeway of a population" (Oswalt, 1970).

- As to the statistical study, culture refers to

academic achievement in history, geography and philosophy.

- Regarding the qualitative study, it refers to general

knowledge: world news, cinema, geographical and historical information, etc.

Linguistic knowledge and

linguistic competence are used interchangeably

to mean the extent and quality of comprehension, writing, grammatical and

vocabulary abilities in a given language. Speaking and listening are not

considered because we are concerned with written translation.

Learning translation and

translation competence acquisition are also

used to mean the same thing: "learning how to translate".

Realia: is used in page 56 to refer to

objects specific to one culture.

Note: Many terms related to translation

studies are cited in the study. We have tried to make sure each first use is

followed by the relevant definition.

Chapter One

LITERATURE REVIEW

Introduction

The major hypothesis underlying the present study states that

the more a student possesses linguistic and cultural knowledge at the beginning

of a translation course, the better he progresses in the process of translation

learning and the more qualified prospective translator he is. Considerable

amount of available literature is related, either directly or indirectly, to

this issue (Mounin, 1976; Pym, 2002; Gouadec, 2000; Gambier, 2000; Hardane,

2000).

The literature review, in its three first parts, directs

attention to the actual objectives of translation course in the light of some

central issues to translation. These central issues are the linguistic and the

cultural knowledge the profession requires, the nature of translation

competence

as opposed to linguistic competence and some aspects of

translation's problems and responsibilities.

The fourth part of the literature review proposes a brief

account of the policies some European and Canadian translation schools adopt in

student admission process. Moreover, it exposes the views of some translation

teachers and scholars concerning the selection question. This description aims

to support what our study advances and recommends.

The fifth part of the review deals with measuring translation

learning progress. As stated earlier, this study intends to evaluate

translation competence of third year translation students. Hence, an evaluation

of their level is needed. This is why a critical description of some of the

available evaluation methods of student translations and Translation Competence

measuring instruments is presented.

1.1. Linguistic and Cultural Knowledge

1.1.1. Translation and Language

Translation can be considered as an attempt to fulfil an act

of communication between two linguistic and cultural communities. The

difference between languages is basically the raison d'être of

translation. This section looks at this difference in order to gain some

insight into the

linguistic task of the translator, and hence, the type and amount

of linguistic knowledge he needs to possess.

1.1.1.1. Differences between languages

Instead of discussing the obvious superficial differences that

exist between languages and that no one fails to notice, it seems preferable to

begin by looking at the very depth of things. In contrast to what things appear

to suggest, a word, within the same linguistic community, does not

represent perfectly the same thing for all people. As early as the

19th century, Humboldt (1880) goes further to say that a word is

nothing but what each individual thinks it is. Georges Mounin (1957), explains

that each word is the sum of each individual's personal and subjective

experience concerning the object this word represents. Therefore, exchanging

words cannot assure a perfect communication of an idea between the members of

the same linguistic community. This is what Humboldt (1880) explains in the

following words:

"[...] chez celui qui assimile comme chez celui qui parle,

cette idée doit sortir de sa propre force intérieure : tout ce

que le premier reçoit consiste uniquement dans l'excitation harmonique

qui le met dans tel ou tel état d'esprit"

(p.25)

Obviously, different individuals perceive the same words in

different ways. This is why the same author suggests:

"Les paroles, même les plus concrètes et les plus

claires, sont loin d'éveiller les idées, les émotions, les

souvenirs que présume celui qui les prononce"

(p.25)

(see translation 2, Appendix C)

It is true that an extremist form of this view may raise a

controversy as to the extent of probable limitations to the communicative

capacity of language. However, recent psycholinguistic research findings

basically agree. They provide considerable evidence that, within the same

linguistic community, individual experience and perception associate different

mental images, from a person to another, with the same linguistic sign (Eco,

1997).

It might be concluded, as formulated by Mounin (1957), that

each language is nothing but the sum of its speakers' individual experiences,

and hence:

"[...] deux langues [...] n'emmagasinent jamais le même

stock d'expériences, d'images, de modes de vie et de pensée,

de

mythes, de conceptions du monde."

(p. 27)

(see translation 3, Appendix B)

Again, some earlier thinkers like Humboldt (1909) and

Schleiermacher (1813) attained this same conclusion as early as the

19th century. The latter put it as follows:

46 [...] chaque langue contient [...] un

système de concepts qui, précisément parce qu'ils se

touchent, s'unissent et se complètent dans la même langue, forment

un tout dont les différentes parties ne correspondent à

aucune de celles du système des autres langues. [...] Car même

l'absolument universel, bien qu'il se trouve hors du domaine de la

particularité, est éclairé et coloré par la

langue."

(p.85)

(see translation 4, Appendix B)

What Schleiermacher (1813) calls un système de

concepts is a human

being's or a group of individuals' system of

relative concepts that seek to

reach absolute concepts. In

other words, it is a tentative knowledge about

the world that constantly attempts to reach perfect accordance

with reality. What he means is that the interaction between the concepts of the

same language community results in a unique organized mixture or

system of concepts. Humboldt (1909) highlights a comparable concept when he

discusses the difference between languages:

"Des langues différentes sont donc comme des synonymes:

chacune exprime le même concept d'une manière un peu autre, avec

telle ou telle autre détermination concomitante, un peu plus haut ou un

peu plus bas sur l'échelle des sensations"

(p. 143)

(see translation 5, Appendix B)

It should be noted that, for Schleiermacher (1813), the real

object of translation is thought, and its real challenge is this

difference between systems of concepts. To clarify this position he further

adds that when translating:

"[...] j'établis ainsi des correspondances -qui ne sont

pas coïncidences- entre les représentations

véhiculées par différents langages, entre l'organisation

des concepts dans des langues

différentes."

(pp. 17-8)

(see translation 6, Appendix B)

Likewise, there is no doubt that this profound difference

between the 'spirits' of languages is associated with differences in lexis,

syntax, phonology and style. This difference is at the very core of the

translation task, and it is what determines the type and amount of the

translator's required linguistic knowledge.

1.1.2. The Translator's Linguistic Knowledge

The linguistic knowledge of two or more languages is what is

generally thought to be equivalent to the concept of ability to translate.

In the next sections, however, evidence will be provided about the

incorrectness of this received belief. Yet, it may be useful to say that this

belief would never exist if linguistic knowledge were of minor importance to

translation. Still, what is generally ignored is the extent to which a

translator's linguistic knowledge must be deep.

The translator's task includes, among other things, deep

comprehension of a source text (ST) and the production of a target text

(TT). What has been so far advanced suggests that profound

differences exist between languages. This gives a clear idea of the complex

operations the translator has to carry out. These involve problem solving,

decision making and responsibility taking. Given this, one can easily imagine

how wide and how subtle the translator's linguistic knowledge should be.

Consequently, a good translator should be more than a good

linguist (Mounin, 1962). All what concerns the languages on which the

translator works should be of interest to him. Language is a changing system,

as a multitude of factors constantly contribute to its shaping and reshaping.

It is, to borrow Schleiermacher's expression (1999), "a historical being".

This implies that the translator's linguistic knowledge should extend to

include every contributory factor in its mode of functioning. This is in order

for him to be able to deeply understand the source language and effectively

produce in the target language.

Moreover, it should be mentioned that what precedes concerns

both knowledge of the foreign language and that of the translator's native

language. As unexpected as it may seem, the translator's competence in his

native language should never be taken for granted.

1.1.2.1. Knowledge of the native language

It seems obvious that the translator already masters his

mother tongue, so all what is left is to work on its perfection through some

final improvements. This is not necessarily the case. Darbelnet (1966) asserts

that this is an illusion emerging from the fluency with which people speak

their native languages. However, once one tries to draw up one's ideas,

difficulties and hesitations arise, which is intolerable to a translator.

The case of Algerian students of translation is even more

concerned by this illusion. Although Arabic is considered, in the context of

the Translation university course, as the students' native language, reality is

significantly different. Classical Arabic, which the students must learn to

translate from and into, is not the language they use in everyday life. This is

why the students' knowledge of Arabic should not be taken at face value

(Hardane, 2000).

In fact, in order to master one's mother tongue, one has to

observe and reflect on linguistic events. Darbelnet (1966) goes further to say

that the translator should know his native language better than does a writer.

Indeed, this latter chooses what to write, whereas what the translator should

write is imposed on him. The following quotation illustrates this

perception:

"Le traducteur ne choisit pas le sujet à traiter.

Quelqu'un l'a déjà choisit pour lui, et il ne sait jamais

à quelles ressources de la langue d'arrivée il devra faire appel

pour rendre une pensée qu'il n'a pas conduite à sa guise mais

qu'il reçoit toute faite."

(p. 5)

(see translation 7, Appendix B)

Similarly, Mounin (1957) quotes two famous French writers

highlighting this underestimated requirement. The first is Marcel Brion (1927)

who wrote in his Cahiers du Sud:

"C'est dans sa propre langue que le traducteur trouve le plus de

difficultés."

(p.19)

(see translation 8, Appendix B)

The second is André Gide (1931) in his "Lettre à

André Thérive":

"Un bon traducteur doit bien savoir la langue de l'auteur qu'il

traduit, mais mieux encore la sienne propre, et j'entends par

là :

non point être capable de l'écrire correctement mais

en

connaître les subtilités, les souplesses, les

ressources cachées."

(p. 19)

(see translation 9, Appendix

B)

1.1.2.2. Knowledge of the foreign language

The simple mastery of the language's lexis and syntax, however

excellent it may be, is not sufficient to be able to translate (Schleiermacher,

1999, p. 15). The translator is not always expected to translate from

the foreign language. He might well be asked to translate into

it. This entails that he should be as competent as possible in this

language in order to be able to effectively and appropriately write in it. This

belief is also shared by Darbelnet (1966).

Understanding appears as a quite complex task because of the

differences between languages in terms of concepts and, of course, forms. Hatim

and Mason (1990) further explain the difficulty of the understanding process in

the following words:

"[...] it is erroneous to assume that the meaning of a

sentence or a text is composed of the sum of the meanings of the individual

lexical items, so that any attempt to translate at this level is

bound to miss important elements of meaning."

(pp. 5-6)

Many subtle language-specific elements determine the meaning

and render understanding even more complex. Word order, sentence length, ways

of presenting information, stylistic features and meaning carried by specific

sound combinations, are but a few examples.

The already mentioned Mounin's belief (1962) that a translator

should be more than a good linguist makes sense when we know that the

translator has to analyse the text to be translated in a way comparable to that

of a linguist. Literary translation, in particular, offers a wide range of

illustrations. Hence, it strongly shows how a translator's linguistic knowledge

should act. This is due to the fact that the very specificity of literature,

and especially poetry, is, as is well known, language-based. The value of a

text may lie in the ambiguity of its discourse, in the individuality of its

style, in the rhythm underlying the choice of its structures, in the music of

the words, in its cohesion and coherence, and the list remains open.

1.1.2.3. Textual knowledge

In order to be able not to overlook these text features,

Christiane Nord (1999) talks about "translational text competence i.e.

what

translators should know about texts". She explains that

this competence includes:

(a) a profound knowledge of how textual communication works;

(b) a good text-production proficiency in the target

linguaculture (linguistic and cultural system);

(c) a good text-analytical proficiency in the source

linguaculture; and

(d) the ability to compare the norms and conventions of

textuality of the source and the target linguacultures (contrastive text

competence). Nord (1999) explains at this level that:

- competence (a) includes aspects of textual

communication. These include skills like text production for specific

purposes and specific addressees, text analysis, and strategies and techniques

of information retrieval.

- and competence (b) is linked to the ability of expression.

It includes the ability to use rhetorical devices. These are used to achieve

specific communicative purposes, like re-writing, re-phrasing, summarizing ,

and producing texts for other purposes. Converting figures, tables, schematic

representations into text, producing written texts on the basis of oral

information, and revising deficient texts are other activities contained in

competence (b).

1.1.2.4. Communicative competence

Given that translation is all about communication, it would be

unacceptable to talk about linguistic competence without pointing at the vital

necessity of communicative competence. Georges Mounin (1973) insists that:

"La traduction n'est difficile que lorsqu'on a appris une

langue autrement qu'en la pratiquant directement en situation de

communication."

(p. 61)

(see translation 10, Appendix C)

The translator's communicative competence then is fundamental

to assure the appropriateness of translation acts, and hence the achievement of

the ultimate aim of translation. Hatim and Mason (1990) assume that:

"[...] the translator's communicative competence is attuned to

what is communicatively appropriate in both SL and TL communities and

individual acts of translation may be evaluated in terms of their

appropriateness to the context of their use."

(p. 33)

1.1.2.5. Controlled linguistic knowledge

Another vital feature of the translator's required linguistic

competence is a separate knowledge of the two different linguistic

worlds. In other words, this knowledge should be free of any sort of

interference. That is to say a perfectly controlled knowledge that should be

the result of a complete cognitive and affective involvement. Titone's (1995)

explanation is clear:

"The linguistic-communicative competence in two

languages/cultures becomes an invaluable asset only if the

whole human personality is complete in its performative, cognitive and in-depth

conscious dimensions, and is therefore involved in controlling the two

communication systems."

(p. 177)

Inevitably, an uncontrolled knowledge of two languages leads

to interference, which might be disastrous to the translation as well as to

both languages. A constant cognitive effort is thus needed to prevent any

interference to take place. This faculty is an aspect of what Titone (1995)

calls linguistic awareness, which "is nothing else but total

self-perception and total self-control" (p. 28).

On the whole, it should be retained, from all the assumptions

advanced so far, that the difference between languages is far from being

superficial. Mastering a language, even one's mother tongue, is hard. Mastering

more than one language is even harder. But mastering two languages in order to

be able to translate is far more complex. Indeed, it should be systematic,

precise, deep, subtle and controlled. The translator needs to transcend the

mere syntactic and lexical competence to establish communication between two

distinct linguistic worlds.

Many other aspects should be characteristic of his linguistic

knowledge. Precise knowledge of the limits of appropriateness in each language

(communicative competence), mastery of textual features and effective writing

devices, awareness of where differences and where similarities lie, are but

some of these aspects. Again, it should be clearly underlined that

consciousness of both linguistic systems as two separate entities is

extremely important to translate safely, without distorting the specificity of

any language.

1.1.3. Translation and Culture

Undoubtedly, language is not a purely linguistic entity. It

has a particularly close relationship with all what has to do with the people

who use it, be it concrete or abstract. That is to say with

culture.

As early as 1813, Schleiermacher states that translating is at

the same time understanding, thinking and communicating. He emphasizes,

however, the act of understanding because of its great proximity to

the act of translation. He thinks that the only difference between translating

and understanding is one of degree. According to this author, translating is a

profound act of understanding, since the primary goal of translation is making

the target reader understand the source text. Accordingly, the translator needs

first to make sure he understands it, which is not as simple a task as it may

seem.

The source text, like all kinds of texts, is an entity of a

very complex nature. Form, content, aim, fonction, aesthetic value and all its

traits are the product of a wide range of overlapping factors. These factors

are those involved in determining the choices that the author, consciously or

unconsciously, makes. Many of these factors are, in a way or in another, a

result of culture.

Culture is defined in the Oxford Advanced Learner's

Dictionary (2000) as "the customs and beliefs, art, way of lifè

and social organization of a particular country or group" (pp.322-323).

Oswalt (1970) provides a similar definition stating that it is the "lifeway

of a population" (p.15). This is referred to as the anthropological

definition of culture (Chastain, 1976, p. 388). Although this definition does

not make it explicit, a group who shares all these very elements cannot but

share an

intelligible linguistic code. Newmark (1988), on the other hand,

maintains this point when defining culture. He states that it is:

"The way of life and its manifestations that are peculiar to a

community that uses a particular language as its means of expression."

(p.94)

This definition clearly links between language and culture, as

it implies the assumption that one linguistic community shares necessarily one

culture. Although this statement may be questionable, it is undoubtedly

justifiable to maintain the close relationship it stresses between language and

culture.

Whereas Newmark's (1988) definition of culture perceives

language as its "means of expression", some linguists believe that the

relationship between language and culture is far more intimate. This view is

referred to as the "Sapir-Whorf hypothesis" after the two linguists Edward

Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf (Trudgill, 1979). It holds that it is, rather,

language that organizes knowledge, categorizes experience and shapes the

peoples' worldview (Trudgill, 1979). As a direct consequence, it shapes

culture. Edward Sapir (1956) claims that the community's language habits

largely determine experience. And in his words:

"No two languages are ever sufficiently similar to be

considered as representing the same social reality. The worlds in which

different societies live are distinct worlds, not merely the same world with

different labels attached."

(p.69)

Nevertheless, the strongest form of this view is now widely

unacceptable, as it implies " the impossibility of effective communication

between the members of different linguistic communities" (De Pedro, 1999,

p.458). It also means that people cannot see the world but from their native

language perspective. This proves wrong when considering that many people

achieve a high degree of competence and fluency in foreign languages. Moreover,

many translators do render meaning appropriately from one language to another.

This might imply that "they are able to conceptualise meaning independently

of a particular language system" (Hatim and Mason, 1990, p. 30).

Juri Lotman (1978), a Russian semiotician, holds an analogous,

but a more moderate, view as to the relation between language and culture. He

declares that:

"No language can exist unless it is steeped in the context of

culture; and no culture can exist which does not have at its center, the

structure of natural language."

(pp. 211-2)

This opposes the belief that the relationship between language

and culture is that of the part to the whole (Torop, 2000). The semiotician

Peeter Torop (2000) sees language as one of the several semiotic systems found

in a given culture. The "semiotic system" he refers to is any sign system, such

as music, dance, painting and the like.

Despite the differences in views as to whether language shapes

culture or not, we can maintain Linguistics' point of view expressed by Mounin

(1973):

"La linguistique formule cette observation en disant que les

langues ne sont pas des calques universels d'une réalité

universelle, mais que chaque langue correspond à une organisation

particulière des données de l'expérience humaine - que

chaque langue découpe l'expérience non linguistique à sa

manière."

(p. 61)

Bassnett (1991) holds the same view when she says that:

"Language [...] is the heart within the body of culture"(p. 14). This

close relationship between language and culture is, in fact, what gives the

translator's cultural knowledge its crucial value.

1.1.4. The Translator's Cultural Knowledge

Culture is thus what explains and clarifies almost every

mystery in a foreign language text, including its language and its author. In

other words, both the language learner and the translator need cultural

knowledge to understand. Schank and Abelson (1977) support this,

saying that: "understanding is knowledge based". Chastain (1976)

states that:

"The ability to interact with speakers of another language

depends not only on language skills but also on comprehension of cultural

habits and expectations. Understanding a second language does not insure

understanding the speaker's actions."

Mounin (1962) claims that:

"Le traducteur ne doit pas se contenter d'être un bon

linguiste, il doit être un excellent ethnographe: ce qui revient à

demander non seulement qu'il sache tout de la langue qu'il traduit, mais aussi

du peuple qui se sert de cette langue."

(p. 50)

(see translation 12, Appendix B)

Therefore, cultural knowledge refers to the knowledge of the way

of life of a linguistic community. This includes every aspect of life: habits,

worldviews, social system, religion, humor, good manners, clothing, etc.

(Chastain, 1976, 389-92).

Given the particular relationship between culture and

language, cultural knowledge is the way for the translator to deeply know the

language. Indeed, culture reveals the language's mode of functioning

Schleiermacher (1813) thinks that it is not acceptable to work on and with

language in an arbitrary way. The authentic meaning of language should be

gradually discovered through history, science and art. This assumption adds

another dimension to the required cultural knowledge of the translator. It is

the intellectual production written in the language in question, and which

contributes, in his view, to the formation of the language (ibid.).

Cultural knowledge does not only help understand a text's

content. It also, as a logical consequence, shows the way in which a particular

foreign reader is best addressed. It provides, hence, access to the first and

the last translation operations, which Schleiermacher (1813) advocated:

understanding and communicating.

So far, we have emphasised the necessity of cultural knowledge

for understanding and communicating. Another facet of this necessity concerns

translating, that is Schleiermacher's thinking. It is the cultural

component of the already presented concept of controlled or separate knowledge.

Incompatibility between cultures should be studied as well. De Pedro (1999)

affirms that: " Translators have to be aware of these gaps, in order to

produce a satisfactory target text" (p.548). In her paper about textual

competence mentioned earlier, Nord (1999) insists on what she calls the

translator's contrastive text competence. In this competence she

highlights the ability to compare and be aware of cultural specificities. She

states that it:

"[...] consists of the ability to analyse the

culture-specificities of textual and other communicative conventions in both

linguacultures, [and] identify culture-bound function markers in texts of

various text types."

Another point cannot be disregarded. It is known that English,

French and even Arabic, like many other languages, may be used by people of

other cultures to produce all types of texts, especially in literature. African

literature written in English and the North African one written in French are

two illustrating examples. Here, the translator is faced with a specific

language embedded in a different culture, which entails a specific task of

analysis based on relevant knowledge. As a result, cultures directly related to

the languages in question are not the only cultures the translator should be

familiar with (Osimo, 2001).

1.1.5. Learning Culture

The translator's required cultural knowledge takes, then, huge

proportions. A study of culture that depends on random exposure to relevant

documents sounds insufficient. For this reason, there stands the need to

systematically and deeply study the culture in question (Mounin, 1962,

Chastain, 1976).

Therefore, if we consider the ways of acquiring cultural

knowledge, we can find, among other things, the following:

a relatively long stay in the country of the language (Mounin,

1962);

a long and systematic exposure (Mounin, 1962) to all types of

authentic material like films in the original version, novels reflecting as

authentically as possible everyday life and discourse, and nonfiction documents

sharing the same characteristics.

Chastain (1976) advances that in an academic context, for

example a language class, teaching the culture of the language must be a

fundamental and systematic component of the curriculum. The

objectives should be made clear to learners, and material acquisition should be

tested rigorously, just as the linguistic material is (pp. 388, 509). Because

the language and its culture are interdependent, the culture of the language

should be given a similar importance to that of the language itself, and be

taught in relation to the corresponding linguistic items (p. 388). It follows

that:

"Ideally, at the end of their studies, the students will

have a functional knowledge of the second culture system as they have of the

second language system"

(Chastain, 1976, p. 388)

All the literature summed up thus far leads to believe that,

in translator training, two conclusions can be drawn. First, learning to

mediate between two languages and cultures whose boundaries are not yet clear

in one's mind seems to be of a questionable value.

Second, such a deep and subtle knowledge appears to be hard to

achieve in such a relatively short time as a four-year translation course. This

suggests that unnecessary loss of time should, as far as possible, be avoided.

This makes sense when we know that the course should include a number of other

subjects to study and other competences to acquire. This is the subject matter

of the following sections.

1.2. Translation Competence

Translation Competence is a key issue in this study.

It is a concept whose nature is generally misunderstood by common people, but

also controversial to translation theorists. This is clearly felt when one

examines relevant literature.

1.2.1. The Term Translation Competence

It should be noted that the definition of the concept is not

the only fundamental issue that has not yet been established, the term

indicating the concept as well. Pym (2002), Campbell (1991), Waddington (2001),

F. Alves; J.L. Vila Real; R. Rothe-Neves (2001) and Orozco and Hurtado Albir

(2002) use Translation Competence. Others have chosen different

appellations. Orozco and Hurtado Albir (2002) mention some of them:

translation transfer (Nord, 1991, p.161), translational

competence

(Toury, 1995, pp.250-51; Hansen, 1997, p.205; Chesterman,

1997, p.147), translator competence (Kiraly, 1995, p.108),

translation performance (Wilss, 1989, p.129), translation ability

(Lowe, 1987, p.57), and translation skill (Lowe, 1987, p.57). All

these denominations are, nevertheless, rarely accompanied with the researcher's

definition of the concept (Orozco and Hurtado Albir, 2002, p.375).

In this study "Translation Competence" is being used.

On the one hand, we accept the concept "competence" as comprising all

the other terms, namely ability, skill and knowledge. The

definition the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary (2000) suggests of

the word competence is "the ability to do something well" (p. 260),

which may entail a wide range of skills, abilities and types of knowledge.

McClelland (1973), on the other hand, defines it as "appropriate use of

specific abilities according to surrounding demands" (Alves; Vila Real;

and Rothe-Neves, 2001). This definition fits the point of view this study

adopts because we believe that the concept of appropriateness is

central to Translation Competence.

On the other hand, the use of the term "translator

competence" might include things that go beyond the concept. Indeed, it

may imply all what a translator should know and be able to do including what

may belong to other fields than translation, such as knowledge about specific

subject matters. However, what we refer to by the term Translation

Competence is only what is specific to translation and

distinct from the other disciplines.

1.2.2. Translation Competence Versus Linguistic

Competence

Early attempts to define translation competence do not

distinguish it from competence in more than one language. Anthony Pym (2002)

attempts to classify the different approaches to the concept since the 1970s.

The first approach he refers to perceives translation competence as a summation

of linguistic competencies. It consists in possessing a "source-language

text-analytical competence" and "a corresponding target-language

text-reproductive competence" (Wilss, 1982, p. 118). Similarly, in Werner

Koller's (1979) words, it is "the ability to put together the linguistic

competencies gained in two languages" (p.40).

This approach raises the following relevant question: "Does

translation competence mean linguistic competence in more than one language?"

Accepting that it does would, in fact, imply the assumption that any person

possessing a sound knowledge in more than one language can necessarily be a

good translator. This, again, suggests that bilingual persons are automatically

skilful translators (Harris, 1977). As a result, deduces Pym (2002), "the

linguistics of bilingualism might thus [...]

become the linguistics of translation, and no separate

academic discipline need develop" (p.3). Furthermore, Translation Studies

would be reduced to a subject within Applied Linguistics, and Translator

Training would be the task of Language departments (ibid.). More

relevant to this study's concern is that this approach implies that Translation

course is all about language learning. This would make the duration of the

course sufficient for students to learn 'translation' perceived in this way.

Prior linguistic and cultural knowledge would then appear unnecessary.

1.2.3. Nature of Translation Competence

The existence of this concept has become undeniable even

through empirical studies, such as that of Waddington (2001). Nonetheless, its

nature raises controversy. Two main approaches to the question are

presented.

The first approach is a set of different attempts to identify

what is included in translation competence. These attempts seem to be more

interested in what the translator's knowledge, abilities and skills should

comprise rather than isolating the concept of translation competence itself.

Pym (2002) mentions some of these views. He states that they all perceive

translation competence as "multicomponential", with a growing

tendency to include in the list of components all what each

theorist thinks necessary for a translator to know and do. This is, probably,

the result of the dramatic change occurring in all aspects of life due to the

development of science, communication and technology. The profession of

translation seems to get more and more complex because of the large number of

the required "market qualifications" of a translator.

Some of the definitions of translation competence belonging to

this category are briefly listed. Roger Bell (1991) perceives translation

competence as the sum of the following: target-language knowledge, texttype

knowledge, source-language knowledge, subject area knowledge, contrastive

knowledge, and communicative competence covering grammar, sociolinguistics and

discourse. Beeby (1996) lists six sub competencies within translation

competence. Each of them includes up to four or five sub-skills. Hewson (1995)

added to the traditional ones a set of other `competencies', where some of

which are "access to and use of proper dictionaries and data banks" (p.

108).

Another example of the "multicomponential" models of

translation competence is that of Jean Vienne (1998). He suggests that the

first required competence is the translator's ability to ask the client about

the target text's readership and purpose. Proper use of the appropriate

resources to reach the client's aim and meet the public's needs constitutes the

second competence. Third, the translator should be able to account

and argue for the decisions he has made in the translation

process. The client needs to agree on whatever modifications brought to form or

content. Finally, the translator should also be able to collaborate with

specialised people in the source text's subject, particularly when they do not

speak his language. He is also required to ask them to explain the subject for

him rather than just teaching him the terminology. Translation implies, above

all, understanding, affirms Vienne (1998).

All the models developed within this trend seem to be

influenced by the complexity of the tasks the modern professional translator is

required to carry out, and the multitude of disciplines he is expected to be

familiar with. This is well explained in the following Pym's (2002)

quotation:

"The evolution of the translation profession itself has

radically fragmented the range of activities involved. In the 1970s,

translators basically translated. In our own age, translators are called upon

to do much more: documentation, terminology, rewriting, and the gamut of

activities associated with the localization industry."

This approach may also be explained by the fact that

Translation Studies as a newly established discipline draws on a wide range of

other disciplines. Pym (2002) continues:

"Perhaps, also, the explosion of components has followed the

evolution of Translation Studies as an "interdiscipline", no longer constrained

by any form of hard-core linguistics. Since any number of neighbouring

disciplines can be drawn on, any number of things can be included under the

label of "translation competence."

(p.6)

The development of the profession or that of the discipline,

however, doesn't necessarily imply to stop distinguishing the required

competence itself from the use of new tools or knowledge in specific

disciplines. These are there to assist the translator in his task, rather than

to add complexity to matters.

An additional critique lies in the question posed by Pym

(2002): Is it possible to include all there skills in the objectives of

translator training programs, given that the Translation course doesn't last

more than four or five years?

The second approach distinguishes between Translation

Competence and the other competencies, but seems to fail to draw clear

boundaries between linguistic competence and translation competence. Vienne

(1998) reports Jean Delisle's (1992) attempt to define the concept, where a set

of five competencies is listed:

Linguistic competence: ability to understand the source language

and produce in the target language.

Translational competence: ability to comprehend the

organisation of meaning in the source text and to render it in the target

language without distortion, in addition to the ability to avoid interference.

Methodological competence: ability to look for and use documentation about a

given subject and learn its terminology. Disciplinary competence: ability to

translate texts in some specific disciplines, like law and economy.

Technical competence: ability to use translation technology

aids.

Jean Vienne (1998) expresses his disappointment of the fact

that Delisle (1992), just like a number of other translation theorists, reduces

translation competence to the "double operation of deverbalization and

reformulation of deverbalized ideas" (p.1). This definition, he thinks, doesn't

deal with the competencies that are actually specific to translators (Vienne,

1998).

In fact, the definition Vienne (1998) rejects has tried to

distinguish between linguistic competence, Translation Competence and other

competencies. The difference between linguistic and Translation Competences is,

nevertheless, believed to be a malter of degree, accuracy and interference. In

other words, according to this definition, a translator should understand a

source text more profoundly and write more effectively than common

linguistically competent people. Moreover, he has to avoid interference and be

faithful and accurate.

Actually, what is thought to be the difference between

linguistic competence and Translation Competence, namely good understanding and

writing, appear to belong to linguistic competence. Avoiding interference,

faithfulness and accuracy, on the other hand, may well be considered to belong

to translation competence. But, are these three elements what translation

competence is all about?

Another attempt to define translation competence is made by

Stansfield et al. (1992). They claim that translation competence should be

divided into two different skills. The first is accuracy, "which is the

degree of accuracy with which the translator transfers the content from the

source to the target text" (Waddington, 2001, p. 312). And the second is

expression, "which refers to the quality of the translator' s expression of

this content in the target language" (Waddington, 2001, p. 312). This

assumption is the conclusion of an empirical study conducted on

translation tests assigned to translators working for the U.S.

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). However, Waddington (2001) criticises

the study on the grounds that the majority of the tests consist of

"multiple-choice tests and the translation of isolated words, expressions or

sentences" rather than texts (p. 313).

A third group of scholars seem to have attained a clearer

conception of Translation Competence nature. They put forward that Translation

Competence is something distinct from both linguistic competence and other

competencies. It lies in the ability to solve translation problems and make

decisions with regards to a multitude of relevant factors, such as the source

text author's purpose and the target readership's needs. This competence is

what highlights translation specificity vis-à-vis other concepts like

bilingualism. Hurtado Albir (1996) defines it as " the ability of knowing how

to translate " (p.48). This implies a certain ability specific to the process

of translating. Gideon Toury (1986) suggests that it is a specific "transfer

competence" which is not the simple overlap between competences in two

languages (Pym, 2002). Werner Koller (1992), in a more recent restatement of

his view, asserts that Translation Competence resides in "the creativity

involved in finding and selecting between equivalents" and in text

production as well (p.20). Similarly, Pym opted for what he calls "a

minimalist" definition of Translation Competence, as opposed to the

multicomponentialist

definition. His definition is based on the generation and the

elimination of alternatives as far as the problem solving process is concerned

(Pym, 2002, p. 10).

As to the formulation of a definition, Hurtado Albir and

Orozco (2002) choose that of Process of the Acquisition of Translation

Competence and Evaluation (PACTE) research group, from the Universitat

Autônoma of Barcelona in Spain. This definition suggests that

Translation Competence is "the underlying system of knowledge and skills

needed to be able to translate" (Orozco and Hurtado Albir, 2002, p.

376).

The "linguistic" approach to Translation Competence, which

reduces it to mere competence in two languages, was subsequently rejected even

by its own followers like Koller (1992). Apart from this approach, all the

other trends argue for the existence of a competence specific to translation

and more or less distinct from language competence. The approach underlying the

present study draws on this assumption along with the conception the third

approach establishes of Translation Competence. We assume that this latter

appears to be the overlap between three types of qualities and practice. The

first quality is a wide and diversified knowledge. The second is related to

cognitive abilities such as inference and memory. And the third concerns some

affective dispositions such as risk-taking and flexibility. This overlap

should result in appropriate performance in problem solving and

decision-making

· tasks constantly involved in translation.

It can also be retained that translation competence concerns

the ability to deal with translation problems. Analysing and

understanding the problem constitute the first step. Then the translator has to

produce several alternative solutions and decide on the selection of the most

appropriate. In this process, every relevant element should

be taken into consideration. Cultural implications, style, the author's

purpose, target readership needs, are some decisive elements.

To train the student translator to deal with translation

problems, practice from the very beginning of the course appears as an

indisputable necessity. What should be realised here is that alternative

generation implies that the student's linguistic knowledge be of a certain

level of variety, particularly in terms of syntax and lexis. Otherwise, the

production of different solutions and formulations would be unattainable. A

certain amount of cultural knowledge allowing for a sound communicative

competence is also required. It is mostly needed for the task of selecting the

most suitable alternative. Undoubtedly, what has been put forward so far

reinforces the belief that previous linguistic and cultural knowledge are

necessary for the translation learning process.

To sum up, all the views agree on the complexity and the

difficulty of the process that entails translation competence. Consequently, as

we

have seen, some of the approaches led to the supposition that

a four or five years translation course is not sufficient (Pym, 2002).

Acquiring translation competence requires the devotion of as much time and

effort as possible. Spending time in basic linguistic and cultural knowledge

acquisition seems to hinder the course objectives' attainment. These are then:

translation competence acquisition and the enrichment of linguistic

and cultural knowledge.

1.2.4. Translation Competence Acquisition and

Language Learning

This section looks at the process of acquiring translation

competence, and examines the interaction, if any, between it and elementary

language learning. Understanding this is expected to help us know more about

the possibility of simultaneous learning of the two. As a matter of fact no

literature has been found to address the issue directly. Therefore, an analysis

of the available findings is needed to uncover the question.

Toury (1986) suggests that translation competence consists in

a natural, innate and mainly linguistic ability very much

developed among bilingual people. He adds that this ability is not sufficient.

The translator should also develop the transfer ability in order to

achieve translation

competence. In this sense, linguistic knowledge is considered to

be a basis upon which translation competence is, subsequently, developed.

Shreve (1997) states that it is a specific competence included

in communicative competence, and that develops from natural translation to

constructed translation. He means by "natural translation" the initial, natural

and potential ability to translate. "Constructed translation" is the developed

competence of translation. In this model, it may be discerned that

"constructed" translation ability develops only after communicative competence

is acquired.

Orozco and Hurtado Albir (2002) adopt the PACTE research

group's model of translation competence acquisition (2000). It suggests that

translation competence "is a dynamic process of building new knowledge on the

basis of the old". This process "requires development from novice knowledge

(pre-translation competence) to expert knowledge (translation competence)"

(p.377). This finally "produces a restructuring and integrated

development of declarative and operative knowledge" (Orozco and Hurtado

Albir, 2002, p. 377). They mean that the learning process builds on previous

knowledge, needed for translation, towards more developed competence. This

involves an interaction between knowledge (declarative knowledge) and practice

(operative knowledge). Expanding on this, it can be deduced that

pre-translation competence (novice knowledge), which most likely refers in part

to previous

linguistic and cultural knowledge, is important as a basis of

translation competence development.

From what precedes, it seems obvious that translation

competence is mainly concerned with the transfer task (Toury, 1986). Evidently,

transfer is much more practice than declarative knowledge internalisation.

Therefore, learning how to transfer involves practice. This entails using

the declarative knowledge. It might thus be justified to assume that at

least basic knowledge of the source and the target languages and cultures is

needed in the process of transfer learning.

More explicit is Darbelnet's statement (1966) that learning

about translation mechanisms is the objective of translation course. Working on

the perfection of linguistic knowledge is also included. However, this does by

no means imply giving separate lectures of grammar or lexis. He goes on

explaining that this would consume a large part of the time we possess. Nord

(2000) is also explicit in this regard:

"An entrance test should ensure that the students have a good

passive and active proficiency in the A-language [the native language]. With

regard to B languages [foreign languages], the entrance

qualifications defined by the institutions have to be tested in order to

prevent translator training from turning

into some kind of foreign language teaching in disguise."

(§. 9)

This assumption is also clearly stated by Osimo (2001) in the

following words:

"Only after having studied one or more foreign languages can one

begin to study translation.

It is in fact necessary to have higher education

qualifications or a university degree in order to be admitted to any

translation course at university level. In both cases, when one sets out to

learn the art of translation, one has already studied languages for some

years.

It is therefore necessary for the aspiring translator to have a

clear idea of certain fundamental differences between learning a foreign

language and learning translation."

("Learning a foreign language versus learning translation" §

1,2,3)

The statements of Darbelnet (1966), Nord (2000), and Osimo

(2001) agree on one idea. There is no time to spend on teaching basic

linguistic material during a translation course. This would suggest that the

selection of the most knowledgeable candidates to be translation learners

is a necessity. Only then, emphasis would be put on the real

objectives of Translator Training

· translation competence acquisition

and the perfection of linguistic and cultural knowledge.

1.3. Some Aspects of the Activity of Translation

1.3.1 Translation Problems

This section is a general account of translation problems, the

main area in which translation competence is at work. It aims to demonstrate

the complexity of translation task, as a permanent problem solving and decision

making process. On the light of these aspects, it addresses the unlikelihood of

acquiring translation competence, along with the required knowledge in a

four-year time course, when the would-be translator does not possess basic

linguistic and cultural knowledge at the beginning of the course.

1.3.1.1. Translatability

The huge conceptual gap between languages and cultures

engendered pessimistic views (Humboldt, 1909; Sapir, 1921). The term

translatability implies a doubt as to whether or not a text, a

structure, an idea or a reality could be translated. This led to the emergence

of the

counter-concept of "untranslatability". It points to

"the [...] impossibility of elaborating concepts in a language different

from that in which they were conceived" (De Pedro, 1999, p. 546). This

approach is referred to as the monadist approach to translatability

(ibid.). There is a belief, for example, that poetry is untranslatable

as its value is based upon its phonological features, which presents

insurmountable difficulties in translation (Firth, 1935).

This concept, though controversial and too pessimistic,

reflects the inevitable loss that translation causes to the original text. This

is quite comprehensible when one considers translation difficulties and

problems.

According to Catford (1965), the difficulties, and sometimes

the quasi-impossibility, of translation belong to two main categories:

linguistic and cultural. The translator is faced, in the former, with the task

of rendering structures usually specific to a language into a different

structural system of another. In the latter, the mission is to convey