|

Lomé (TOGO), September 2018

Universitat Oberta de Catalunya

The role of the African Union in the

resolution

of the conflict in Mali

Master degree in Conflictology

Student : Akala Akizi-Egnim Counsellor :

Andreu Solà

Academic year : 2016 - 2018

ii

Contents

Table des matières

Contents ii

Appendices: figures iv

Abstract v

Introduction 1

1- Background of the study 1

1.1- Africa: a continent of conflicts and political crisis 1

1.2- In search of effective solutions 1

1.3- Persisting nature of conflicts and the eruption of Mali

crisis 3

2- Research questions 3

3- Rationale 3

4- Objectives 4

4.1- General objective 4

4.2- Specific objectives 4

5- Sphere of application and target group 4

6- Structure 4

Chapter 1: THEORETICAL, METHODOLOGICAL AND CONTEXTUAL FRAMEWORKS

6

1- Theoretical framework 6

1.1- Definition of concepts 6

1.2- Theories of intrastate conflicts 7

1.3- The African Union and the conflict intervention framework.

12

1.4- Literature review 18

2- Methodological framework 24

3- The contextual framework: Description of the study area 25

3.1- Geography 25

3.2- History 26

3.3- Demographics 27

3.4- Political sphere 28

3.5- Economy 28

Chapter 2: THE ARMED CONFLICT IN MALI 30

1- An overview of the conflict 30

2- Humanitarian impact of the conflict 33

3- The causes of the conflict 33

3.1- Structural causes 34

3.2- Proximate causes or triggers of the conflict 40

4- The actors of the armed conflict 42

iii

4.1- The national warring actors and their interests 42

4.2- Relations between armed groups: interactions and coalitions

45

4.2- International Organizations and Governments' intervention

47

Chapter 3: AFRICAN UNION INTERVENTION: Strengths and challenges

49

1- The intervention process 49

1.1- Overview of diplomatic and political efforts 49

1.1.1- Early warnings 49

1.1.2- The Framework Agreement with CNRDRE, April 2012 50

1.1.3- The Ouagadougou Peace Processes and Agreement, December

2012; June 2013 51

1.1.4- Post military intervention mediation 51

1.1.5- From Ouagadougou to Algiers: the Inter-Malian Inclusive

Peace Talks, 2014-2015 52

1.2- The Military efforts 53

1.2.1- From the idea of MICEMA to the establishment and

Evolution of AFISMA 53

1.3- Some post-conflict Reconstruction and Development

initiatives 55

2- Difficulties and challenges met by the AU in the intervention

56

2.1- The limitations of African Peace and Security Architecture

56

2.2- The lack or insufficiency of finance and logistics. 58

2.3- The lack of fair cooperation from UN and UN funders 59

2.4- The operational challenges of AFISMA in the field 59

3- Recommendations 60

3.1- Towards an efficient AU 60

3.2- For an effective and lasting peace in Mali 63

Conclusion 65

Bibliography 67

Annexes 70

iv

Appendices: figures

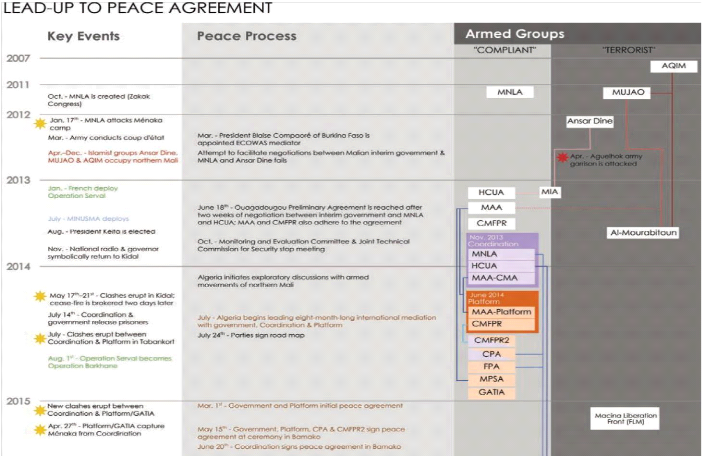

Figure 1: Summary of some key Timelines of the Mali Conflict

from 2011 to October 2015 71

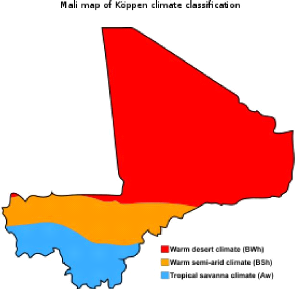

Figure 2 : Map Mali climate 75

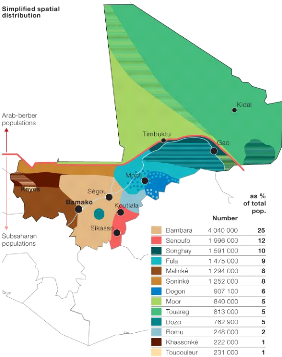

Figure 3: Map Mali spatial distribution of ethnic groups in

Mali 76

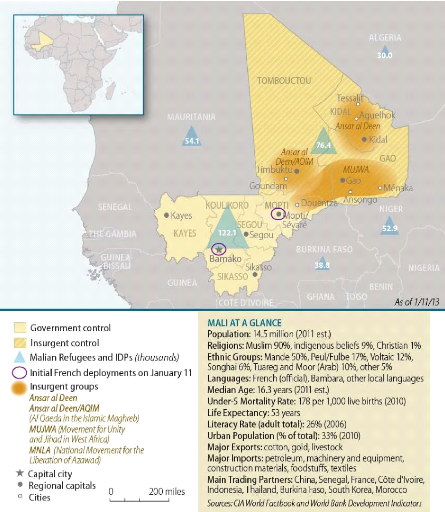

Figure 4: Map of Mali as of January 11, 2013 77

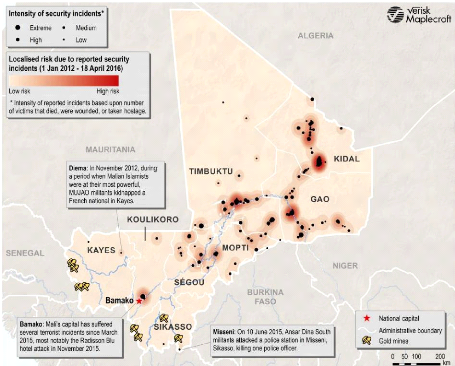

Figure 5: Map of Intensity of security incidents in Mali till

April 2016 78

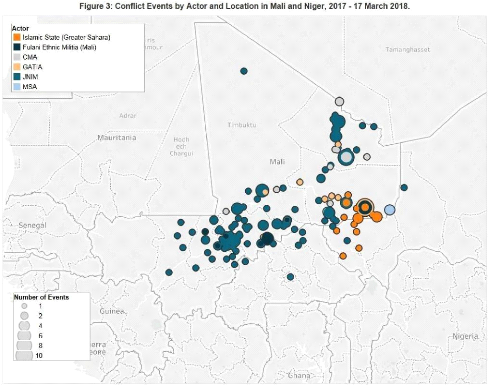

Figure 6: Conflict events by actors and location in Mali and

Niger 2017-2018 79

Figure 7: Leadership of Mali peace agreement 80

Figure 8Implementatiuon of Bamako Agreement 81

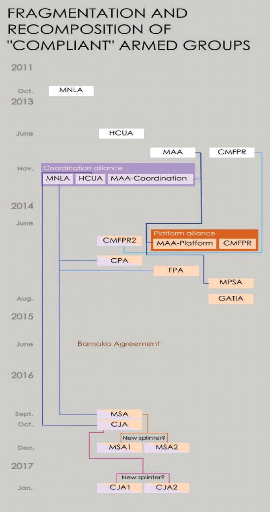

Figure 9: Fragmentation and recomposition of compliant armed

groups 82

v

Abstract

In the final decade of the 20th century, the mounting need for

greater continental integration resulted in the transformation of OAU in to AU

(African Union) in 2002. Among the priority agendas of the new organization are

issues of peace and security on the continent. Despite the commitment and

efforts to build institutional capacity to confront problems, objective

realities on the ground reflect that situations of political instabilities and

armed conflict in the continent are far from significantly resolved. The Malian

crisis which unfolded from 2012 is one of the examples of the limits of the new

organization in preventing and addressing effectively crisis.

The study identified the Malian crisis with issues of

political and economic marginalization, poor governance leading to ethnic

dissatisfaction and rebellions, and expressions of some form of religious

radicalism and criminal networks that involves actors respective to each of the

factors.

Moreover, the researcher has explored the intervention of the

AU and its RECs/RMs on the one hand, and on the other hand, portrayed the

challenges these regional organizations are facing in the maintenance of

continental Peace and Security in light of the Malian political crisis with

regard to their lack of capacity to conduct peace operations including

insufficient financial and logistic support, lack of cooperation and tensions

within the organizations and with the UN. Finally the researcher has suggested

some solutions for the way forward.

1

Introduction

1- Background of the study

1.1- Africa: a continent of conflicts and political crisis

Africa has been a theater of armed conflicts in a manner that

it is typical continental experience. Roughly thirty percent of conflicts over

the past five decades have occurred in Africa causing twice as many fatalities

as conflicts in other regions (Hoeffler, 2014). These conflicts, mainly

intra-state conflicts, have brought many of African economies to the brink of

collapse along with the loss of millions of lives, widespread displacement and

a wide array of human rights abuses (Ndiho, 2010). For instance, for decades,

countries such as Democratic Republic of Congo, Central Africa, Angola,

Liberia, Sierra Leone, Côte d'Ivoire and Guinea- Bissau, etc, were

crippled by conflicts and civil strife in which violence and incessant killings

were prevalent. Alao (2000) argues that these violent conflicts are very often

characterized by the following patterns:

(a) tensions between sub-national groups stemming from the

collapse of old patterns of relationships that provided the framework for

collaboration among the many ethnic groups in most states;

(b) disputes over resource sharing arising from gross

disparities in wealth among different groups within the same countries and the

consequent struggles for reform of economic systems to ensure an equitable

distribution of economic power;

(c) struggles for democratization, good governance and reform

of political systems;

(d) crises resulting from the systemic failures in the

administration of justice and the inability of states to guarantee the security

of the population;

(e) clashes relating to religious cleavages and religious

fundamentalism.

1.2- In search of effective solutions

It was with the aim to address such conflicts that arose since

the independence that the first continental organization by the name the

Organization of African Unity (OAU) was created in 1963 so that problems of

Africa could be solved by the Africans themselves. However, while OAU was

supposed to be praised for its achievement in supporting efforts to eradicate

colonialism from the continent, it failed to effectively address issues related

with its legacies. Particularly crisis related with ethnicity and the quest for

democracy are said to be challenges that the organization failed to tackle in

its capacity. For instance, the organization had been blamed for inaction to

stop the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, and in not finding lasting solutions to the

conflict in the DRC, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Somalia and Sudan, among others.

The drawback in this respect is to some extent attributed to the provisions

within the charter that

2

established OAU which hampered its operation significantly.

Particularly the concern for respecting sovereignty of member states was

supposed to be obstacles that curtailed most of its aspiration.

Consequently there arose a need for more effective

organizational framework to address the practical political, economic, social,

etc issues in order for a bright continental future. This resulted in the

transformation of OAU into AU (African Union) in 2002 with a lot of hopes and

expectations. Among the agendas with due concern in the new organization was

the issue of peace and security. In line with this, the Protocol relating to

the establishment of the Peace and Security Council (PSC), which was ratified

by the requisite number of member States in December 2003, commits the AU to

work towards the well-being of the African people and their environment, as

well as the creation of conditions conducive to sustainable development.

Furthermore, it calls for the promotion of democratic practices, good

governance, the rule of law, protection of human rights and fundamental

freedoms, respect for the sanctity of human life and international humanitarian

law by member States (PSC, art 2). The Constitutive Act and the PSC Protocol

gives the AU the power to create the structures and processes necessary for the

establishment of a comprehensive peace and security architecture for the

Continent. This architecture includes the PSC, the AU Commission, the Panel of

the Wise, the African Standby Force (ASF), and the Continental Early Warning

System (CEWS). The PSC Protocol also provides for closer collaboration between

the AU and the Regional Mechanisms for Conflict Prevention, Management and

Resolution (AU, 2002).

With these norms, values, and principles, the AU since 2004

have taken initiatives with significant success. According to (Ndiho, 2010), in

1990, there were about 20 wars going on simultaneously in Africa but by 2010,

there were only four ongoing wars and this is a big success story for AU. For

example effective measures were taken against States with unconstitutional

changes of government, particularly the coup d'état in the Central

African Republic (2003), Guinea Bissau (2003 and 2012), Sao Tome and Principe

(2003), Togo (2005), Mauritania (2005 and 2008), Guinea (2008), Madagascar

(2009), and Niger (2010) (Col. Abiodun Joseph Oluwadare, 2015). The council has

also been able to authorize peace operations in Burundi, Somalia, Sudan, and

the Comoros. AU's first mission was deployed in Burundi where transition to

self-rule was characterized by ethnic violence between the Hutu majority and

the Tutsi minority. The mission was described as one of the AU's biggest

success stories as it made concerted efforts to prevent genocides in the Great

Lakes region, and played a crucial role in the ceasefire negotiations.

Besides, the AU Commission also provided strategic, political,

technical, and planning support to operations authorized by the Peace and

Security Council and carried out by regional coalitions of Member States,

Regional Economic Communities (RECs), or Regional Mechanisms for Conflict

Prevention, Management and Resolution (RMs). Such support includes the Regional

Cooperation Initiative against the Lord's Resistance Army (RCI-LRA) and the

operation against Boko Haram undertaken by the Lake Chad Basin Commission and

Benin - the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF).

3

1.3- Persisting nature of conflicts and the eruption of Mali

crisis

Despite the forthright initiatives of the AU in conflict

resolution, Africa Briefing Report (2011), says there remains a discrepancy

between the AU capacity on paper and its actual impact in crisis situations as

incidents of violent conflicts have persisted in Africa. Old conflicts have

continued in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Somalia, and Sudan, as

well as in the Central African Republic (CAR). To this are added emerging

conflicts including a wave emanating from uprising against sit-tight and

despotic leaders which covered North Africa, from Tunisia, Egypt to Libya in

2011, which culminated by the eruption in 2012 of the devastating armed

conflict in Mali with imposing new challenges in the Sahelo-Saharan region.

To respond to this last crisis, the African Union along with

its Regional Economic community (REC), ECOWAS engaged very early in the

conflict through preventive and peacekeeping measures to bring African

solutions to African problems. Unfortunately, once again, the continental body

was not successful as expected. Neither the diplomatic nor the military

initiatives could prevent the crisis from escalating. The Western solutions

were therefore called upon to help stabilize Mali. This resulted in the

deployment of the «operation Serval» by French, the change of AFISMA

by MINUSMA. Furthermore, even if the AU was part of the Algerian peace process,

it was not the main actor.

2- Research questions

The situation of armed conflicts in Africa in light of the

ongoing Malian crisis raises the question of Africa's capability and commitment

to solve its own problems. Is the African Union and its sub-regional

organizations, doing enough to prevent and resolve conflicts on the continent?

What prevents the African continental organization to fully operationalize the

peace and security framework? What can be the possible measures to find

«African solutions to African problems»? These are the questions

which are raised and this study will try to find some answers.

3- Rationale

This issue is worth studying given the fact that peace and

security are necessary precondition for sustainable growth and development any

nation aspires to bring about. Besides, for continents like Africa where there

exist a great deal of records of conflicts and in fact still a political

reality today, researches aimed at searching for alternative ways to deal with

issue of peace and security are by far important. Specifically this study is

claimed to be significant in two dimensions. In the first place, it tries to

unfold the continental potential and practical capacity at the disposal of the

continental organization (AU) to address peace and security. Secondly it tries

to explore the Malian problem in light of the continental initiative to deal

with the challenge of peace and security, so that it is possible to

4

understand the gaps between potentials and practical

capacities of Africans in solving African problems and suggest ways forward.

4- Objectives 4.1- General objective

The basic objective of this study is to analyze the status of

the African Union in discharging its responsibilities with respect to

maintaining continental peace and security in light of the Malian political

crisis.

4.2- Specific objectives

In specific terms this study is supposed to:

- Identify the root causes of the Malian political crisis;

- Identify the Actors in the Malian political crisis;

- Portray the consequences of the Malian political crisis;

- Illustrate the role of AU in dealing with the Malian political

crisis;

- Show the challenges AU faced in the Malian political

crisis;

- Ascertain what the African Union must do for the Union to

remain effective in African conflict

resolution.

5- Sphere of application and target group

It is intended that the outcome of this study will help to

stimulate further debate in the area of conflict resolution in Africa. In

addition to the above, the study will generate debate with regards to the

relevance of the AU in conflict resolution in Africa. This is against the

background of the verdict of irrelevance, seemingly given to the defunct OAU

and some suggestions to the effect that the AU has not been significantly

effective in the resolution of African crisis.

Findings of the study will therefore be useful in the

re-positioning of the African Union (AU), for optimal performance in conflict

resolution. In addition to the foregoing, findings of the study will be useful

to the political elite in Africa, in instituting best practices in their

policies and politics, as it is the absence of such progressive political

practices that bring about violent political conflicts. African and non-African

leaders at other non-political levels, will also find beneficial, the findings

of the study, as issues of conflict resolution cut across leadership

spheres.

6- Structure

The dissertation is structured around three (03) chapters. The

first chapter deals with the theoretical and methodological frameworks

including on the one hand the definition of concepts and the relevant

5

theories developed in the analysis of armed conflicts along

with the literature review and the AU framework in dealing with conflict

prevention and resolution, and on the other hand the methodology used for this

study as well as the description of the study area.

The second chapter deals with the analysis of the Malian armed

conflict including an overview of the conflict, the impact, the root causes as

well as the actors of the conflict.

The third chapter provides, the practical conflict resolution

efforts undertaken by the sub-regional (ECOWAS) and regional (AU) actors in the

Malian conflict. This includes the political and diplomatic efforts as well as

the military efforts deployed in support of diplomatic ones. Finally, some

observations related to the challenges and limits of the initiatives resulting

from the gap existing between the theoretical provisions and the practical

aspects of AU peace intervention lead to the formulation of some

recommendations on the way forward.

6

Chapter 1: THEORETICAL, METHODOLOGICAL AND CONTEXTUAL

FRAMEWORKS

1- Theoretical framework

1.1- Definition of concepts

Conflict

The word "conflict" remains a very ambiguous word and is

therefore taken as an umbrella term that can be used to refer to diverse

situations. Scholars such as Rubin et al. (1994), Lewicki et al.

(1997) consider conflict to be «the interaction of interdependent

people who perceived incompatible goals and interference from each other in

achieving those goals». Barki and Hartwick (2004) elaborated upon

these efforts by defining conflict as «a dynamic process that occurs

between interdependent parties as they experience negative emotional reactions

to perceived disagreements and interference with the attainment of their

goals». According to the Responding to Conflict (RTC)1,

conflict is «a relationship between two or more parties (individuals

or groups) who have, or think they have, incompatible goals.» From

this definition, there is no conflict as long as parties or actors do not

recognize that the situation is problematic and conflictual. However, it is not

because a situation is not recognized as a conflict that there is no latent

problem slowly growing and dividing parties.

Conflict can therefore be described as a disagreement among

groups or individuals characterized by antagonism. This is usually fueled by

the opposition of one party to another, in an attempt to reach an objective

different from that of the other party. Defined this way, conflict can be seen

as an inevitable part of life. Each of us possesses our own opinions, ideas and

sets of beliefs. We have our own ways of looking at things and we act according

to what we think is proper. As such conflicts are daily occurrences with family

members, friends, strangers, colleagues, etc.

Experience in human society has shown that there are degrees

of variation in conflicts. Conflicts are classified in types. Psychology as a

discipline has espoused on intra-personal conflict. Sociology identifies

inter-personal and intra-group or intra-unit conflict, as well as inter-group

conflict.

Conflict should normally be an opportunity for growth and can

be an effective means of opening up among groups or individuals. But when the

conflict is unsolved or not transformed properly, it takes more complex

dimensions with polarizations yielding to hostility, violence and armed

conflict.

1 RTC is a non-governmental organization that works

to transform conflict and build peace by working alongside people living in

situations of conflict and violence to develop the skills, knowledge and

confidence to create and implement strategies for peace.

7

Violent or Armed Conflict

According to Dan Smith (2001), violent or armed conflict is

defined as open, armed clashes between two or more centrally organized parties,

with continuity between the clashes, in disputes about power over government

and territory. In international relations, this type of conflict can be

interstate or intrastrate. While Interstate armed conflict is a conflict

between two or more states who use their respective national forces in the

conflict, intrastate violent conflict is describes as sustained political

violence that takes place between armed groups representing the state, and one

or more non-state groups. Violence of this sort usually is confined within the

borders of a single state, but can have significant international dimensions

and holds the risk of spilling over into bordering states.

Before and during the Cold War, interstates armed conflicts

were predominant in the world, but since the end of the Cold War, the most

common form of conflict is the intrastate violence. Smith says that of the 118

armed conflicts which ensued from 1990, only ten can be strictly defined as

interstate conflicts, more than hundred are intrastate conflicts. With the

increasing number of intrastate armed conflicts, more attention is given by

scholars who develop different theories to help understand the new trends.

1.2- Theories of intrastate conflicts

For the purpose of coming up with a comprehensive

understanding of the Malian complex armed conflict, two types of theories of

conflict are used in this study. The first ones are theories put forward to

explain causes of conflict and the second ones are theories for conflict

pacification or resolution.

1.2.1- Theories of the causes of intrastate

conflicts

There are several theories developed by scholars to explain

the causes of conflict. However, for the sake of this study, we shall deal with

structural theory of conflict, Marxist theory, international capitalist theory

and the economic theory of conflict, as they account better for the conflict in

Mali.

1.2.1.1- The structural theory of conflict

The structural theory attempts to explain conflict as a

product of the tension that arises when groups compete for scarce recourses.

The central argument in this sociological theory is that conflict is built into

the particular ways societies are structured or organized. It describes the

condition of the society and how such condition or environment can create

conflict. The proponents of the structural conflict theory among who Oakland

(2005) identifies such conditions as social exclusion, deprivation, class

inequalities, injustice, political marginalization, gender imbalances, racial

segregation, economic exploitation and the likes, all of which often lead to

conflict. Earlier in 1835, de Tocqueville had the same analysis of the main

causes of the conflicts when he said «Remove the secondary causes that

have produced the great convulsions of the world and you will almost always

find the principle of inequality

8

at the bottom. Either the poor have attempted to plunder

the rich, or the rich to enslave the poor....» (quote from quote from

1954 edition,: 266). Seema Khan (2012) points out that «there are

close links

between social exclusion and conflict and insecurity, both

in terms of causes and consequences. There are now convincing arguments that

some forms of social exclusion generate the conditions in which conflict can

arise. This can range from civil unrest to violent armed conflict and terrorist

activity. Severely disadvantaged groups with shared characteristics (such as

ethnicity or religion) may resort to violent conflict in order to claim their

rights and redress inequalities. ... Social exclusion and horizontal

inequalities provide fertile ground for violent mobilization.»

According to several scholars, many armed conflicts in Africa

fall within this theory. For example, Clionadh Raleigh (2010) says that the

critical factor leading to violent conflicts in sub-Saharan Africa

is the extent of political and economic marginalization. In an

article2 Douma (2006) has examined how the partiality of some state

policies regarding resource distribution promotes inter-group inequality and

contributes to violence sub-Saharan Africa.

Talking of the causes of the conflict in Mali, Sidibé

(2012), says that the attempts since 1960s to challenge state authority relate

to the marginalization of Tuareg and Arab nomadic communities living

in the north of Mali. The ICCT (International center for

Counter-terrorism) in the publication «Is all

about terrorism?» also mentions that the

conflictual dynamics of the Malian conflict are partially linked to the

historical marginalization of the North by the central government of Bamako as

the Tuareg groups

were perceived as an obstacle towards the country's unity, and

therefore have often been marginalized and discriminated by the national

institutions. For Nizeimana & al (2015), decades of marginalization,

discrimination and exclusion from the political and economic processes by the

successive Bamako based governments remained the major uniting force that led

the Tuareg to take arms fighting for a separatist state and the rights of the

Tuareg minorities in Northern Mali.

In view of the above, it can be said that the structuralism

theory accounts to some extent to the causes of conflicts emergence. The theory

is however deficient in its one-sidedness of looking at causes of

conflict. For instance, it does not see the bright sides of

racial or ethnic diversity and the strength that a society may derive from

pluralism. The structural theory thus makes sense only when conflicts are

viewed from the broadest possible perspective, and only if the observer opts to

ignore alternate causes of the conflict. Many conflicts including the conflict

in Mali are determined by other major factors.

1.2.1.2- International Capitalism Theory of conflict

This theory captures the historical import of colonialism and

imperialism. According to Hobson (2006), the external drive of western nations

propelled by the Industrial Revolution created numerous platforms for conflict.

The search for raw materials, need to invest surplus capital and search for new

markets

2 Douma, P. (2006). Poverty, Relative Deprivation

and Political Exclusion as Drivers of Violent Conflict in Sub Saharan Africa.

Journal on Science and World Affairs, 2(2), 59-69

9

outside Europe compelled an imperialist pathway as the western

countries desperately sought such markets, raw materials and investment

climates at the expense of the peace and prosperity of the locals in what is

now known as the Global South. This led to colonization, as well as collision

of cultures and civilizations and ultimately conflict. Hyde (2016) in his

«Are colonial-era borders drawn by Europeans holding Africa

back?» reports that African scholars have long maintained that the

national borders in Africa, most of which date back to the period in the late

1800s when European powers divided up most of the continent in a flurry of

diplomatic agreements and colonial wars now known as the «Scramble for

Africa,» are actually one of the biggest sources of its present-day strife

and violence. In his study «The political and economic legacy of

colonialism in the post-independence African States», Bayeh (2015)

shares the same view noting that colonialism has impacted the political and

economic conditions of the contemporary Africa. He argues that

post-independence African political system is characterized by ethnic based

exclusion and marginalization. Moreover, he supports that corrupt behavior of

the contemporary leaders of Africa is also a contribution of the colonial

experience. The author also puts forward that African resources are extensively

exploited by colonizers, thereby rendering Africa economically weak and looser

in its interaction with the global economy. Supporting the same idea,

Ylönen (2009) says that the colonizers constructed the states in Africa

around a small, ruling elite, demarcating borders according to colonial

territorial holdings, not along ethnic communities, and tended to practice the

strategy of 'divide and rule' to minimize local challenges against the colonial

authority. For him, the attempt to create sufficient political order to

maximize the extraction of resources with minimum investment, the colonial

policies encouraged demographic and regional marginalization of state

peripheries and promoted economic, political, and social inequalities and

imbalances.

In another article entitled «The legacy of

colonialism in the contemporary Africa: a cause for intrastate and interstate

conflicts», Bayeh (2015) stresses on the contribution of colonial

legacy in the contemporary African problems. The study show that the arbitrary

colonial division of African borders contributed a lot for the contemporary

African problems. He explained that blind partition of African borders caused

the disintegration of some ethnic groups into different countries and the

merging together of different ethnic groups into some countries. This, in turn,

resulted in several intrastate and interstate conflicts. Rwanda, Nigeria and

Sudan are taken as typical examples for the first case while Kenya-Somalia and

Ethio-Somalia conflicts for the second case.

As for the conflict in Mali, Amadou Sy3 argues that

«to understand the ethnic roots of the conflict, it's useful to go

back to the colonial period. ... At the Berlin Conference of 1884-5,

imperialist European powers carved up North African territory, creating a

variety of artificial territories before forcing the indigenous populations

into labor.... When Mali became independent, you had nomadic tribes [namely the

Tuareg] who were really by nature not residents of one particular region; they

were migrating from one country to another. Thus, in Mali, the Tuareg were

politically excluded, and their nomadic lifestyle

3 Amadou Sy, a senior fellow in the Africa Growth

Initiative at the Brookings Institution.

10

was threatened by the dictates of the post-imperialist

borders.» In his «Mali: Tuareg problem, a baby of French

colonialism», Murava (2016) also argues that the conflict in Mali has

its roots in colonialism. He explains that before the colonial period the

Tuareg controlled the inter-Saharan trade routes and saw themselves as `masters

of the desert'. But during colonial era, the French found Tuareg dominance

incompatible with their goal of expanding the French empire, and therefore

sought to weaken the Tuareg stronghold. Suddenly Tuareg became minorities in

several new states, and in Mali in particular, a minority ruled by the

population they previously had viewed as `inferior' and historically had

directed slave raids towards.

1.2.1.3- Economic theory of conflict

The economic theory of conflict explicates the economic

undercurrents in conflict causation. All other theories have a link with the

economic theory as the latter includes all the impacts of these theories. There

is considerable interface between politics (power, resources or value) and

scarcity. People seek power because it is a means to an end, more often,

economic ends. Communities feud over farmlands, grazing fields, water resource,

etc, and groups fight government over allocation of resources or revenue.

Scarcity, wants, needs, or the fear of scarcity is often a driving force for

political power, contention for resource control, and so forth. Conflict is

thus not far-fetched in the course of such palpable fear or threat of scarcity.

Just as the fear of poverty and deprivation could lead to fraud or corruption;

so is threat of or real famine, deprivation, mismanagement of scarce resources,

could propel conflict over resource control.

Nizeimana & Nhema (2015) underline that the exclusionary

political systems in Africa have created an environment in which various groups

contending for power are excluded from the political and economic processes

through various repressive measures and the 2012 crisis is an event that

testifies to this assertion. In the view of Francis (2013), poverty, poor

governance, marginalization, the exclusion of a large section of the Malian

populace from the political and the economic process and the failure to address

fundamental grievances by the ruling class in Mali created a breeding ground

for the Tuareg people to gain a foothold and organize themselves.

While the above discussed theories are meant to show

explanations for the outbreak of intra-state conflicts, there are other

theories used to analyze the steps that need to be taken to pacify states

failed into civil conflict. They are Democratic Peace (idealists) and Realist

Theories.

11

1.2.2- Theories of armed conflicts resolution 1.2.2.1- The

idealist theory

Democratic peace theory (idealists) see the intrastate armed

conflicts as a result of lack of democracy. For the proponents of this theory,

the priority step that should be taken to stabilize states failed into armed

conflict is to build institution of democracy (Carothers, 2007). They claim

that a state suffering from turmoil of armed conflict needs to deal with the

question of attaining popular legitimacy to end the state of political

instability. Siegle & al (2004) holds that it is essential to restore trust

in any divided society following civil war, by first building regimes enjoying

popular legitimacy based on the institutional foundations of representative

democracy, exemplified by holding competitive multiparty elections, building

power sharing arrangements into constitutional settlements, strengthening

legislatures and independent judiciary, expanding civil society, and

decentralizing governance.

Accounting for the above arguments, Michael (2010) states

that, first, democracy provides opportunities for expression of discontent in

an open manner that reduces the possibilities of emergence of extreme violence

and at the same time it helps to build trust among the people. They also

consider that democratic type of regime constrains governments from repressive

acts against their own citizens and thus reduces the causes of home-grown

conflict. Democracy curtails the repressive acts against citizens through the

mechanism of voice, since elected governments can be voted out of office, and

through the mechanism of veto, since institutions check executive power

(Christian, 2007).

Generally the idealist theory while having logic and rationale

arguments, its implementation in the real world seems far from practical since

the condition of instability by itself that characterizes states fall in to

civil conflict, is not permissive to undertake the necessary steps to build

institutions of democracy. Nevertheless, there are instances in which attempts

are being made to set up institutional framework for states emerging out of

civil war including the elections held as part of democratic reconstruction to

end the Malian crisis in mid-2013. But this was possible and successful, as

military intervention for enforcement advocated by the realists was associated

to the process.

1.2.2.2- The realist theory

Contrary to the idealists, the realists argue that democratic

institutions are identified with limited capacity to deal with risk of conflict

recurrence in a divided society since they are vulnerable to lingering

disagreements about power sharing arrangements and hence rendering

opportunities for continued insurgency to take place (Hegre & Fjeld, 2010).

They hold the view that the first priority in the peace building and

reconstruction process following an internal conflict is state-building

designed to expand governance capacity and establish conditions of social

cohesion, order and stability, national unity, the rule of law, and the

exercise of effective authority. For the proponents of the theory,

«State-building» is understood as an essential pre-condition for

subsequent developments towards democracy, through the

12

usual mechanisms of holding competitive elections,

strengthening legislatures, and establishing independent checks and balances

upon the executive. Proponents of the realist view were motivated by the

political experiences of states beginning from the post-colonial African

nations up to the recent cases of civil unrest in states like Iraq,

Afghanistan, Syria and some states in Africa. Fukuyama (2004) emphasizes that

state building specially in multicultural societies require authorities to use

force to disarm the militia and establish legitimate control over national

territories. If elections are held prior to accomplishing such processes,

internal conflicts may be frozen prolonging instability. More over Toft (2010)

argues even to the extent of the fact that civil wars ending with military

victories, where one side maintains control of the military and police,

generate more durable order and stability. Particularly they claim that

elections are especially dangerous if held early in any transition process,

before the mechanisms of political accountability, institutional checks and

balances, and a democratic culture have had time to develop (Edward & Jack,

2007).

Finally with regard to the current Malian crisis, there is

fair deal of practical experiences representing the realist view as most of the

initiatives to deal with the turmoil were inclined to the military option as

priority measure in state reconstruction. The government with the support of

forces from the French and the African led Support Mission to Mali (AFISMA) and

later on MINUSMA, the G5 forces perused a military campaign to curb the rebel

forces.

As a conclusion, each theory offer useful tools and insights

in the study of intra-state conflict analysis and conflict settlement. Yet,

with regard to the complexities of armed conflicts, in particular the armed

conflict in Mali, no single theory exits that can comprehensively explain them

by itself. So, this accounts for why I have integrated all these theories that

I consider to be complementary for a better understanding and settlement of the

armed conflict in Mali.

1.3- The African Union and the conflict intervention

framework.

Prior to the birth of the AU, the OAU Heads of State and

government recognized in their declaration in 1990 that the prevalence of

conflicts in Africa was seriously impeding their collective and individual

efforts to deal with the continent's economic problems. Consequently, they

resolved to work together toward the peaceful and rapid resolution of

conflicts. During the OAU Summit held in Cairo in 1993, African leaders

established the Mechanism for Conflict Prevention, Management, and Resolution

(MCPMR). In doing so, they recognized that the resolution of conflicts is a

precondition for the creation of peace and stability, and a necessary

precondition for social and economic development (UN, 2004:1). However, while

this initiative thrust the OAU into the center of conflict management efforts

in Africa, the reality is that the pan-African organization never became a

principal player in the peace processes

13

in Africa (CSIS, 2004:2). This is why it was found necessary

to transform the OAU in African Union with new policies and perspectives.

1.3.1- The African Union

The Sirte Declaration led to the establishment of the AU

(African Union) in 2002 replacing the former OAU (Organization of African

union). The AU's Constitutive Act places a premium on the promotion of peace,

security and stability in Africa (Article 3 (f)). Also enshrined in its

principles are the peaceful resolution of conflicts; prohibition of the use of

force or threats to use force; and, unlike the OAU, rights to intervene in the

affairs of member states in «grave circumstances» related to war

crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity (Articles 4 (c ), (f) and (h)). It

was also intended to avoid over-reliance on UN PKOs (United Nations

Peacekeeping Operations) by seeking `African solutions to African problems'.

The Constitutive Act provides for several institutions to

carry out the operations of the AU. These include the Assembly, the Executive

Council, the Pan-African Parliament, the African Court of Justice, The

Commission, the Committee of Permanent Representatives, the Specialized

Technical Committee, and the Economic, Social and Cultural Council. The AU has

a number of special programs to facilitate its vision and quicken the

realization of its goals. These are NEPAD, the African Peer Review Mechanism

(APRM) and the Conference on Security Stability Development and Cooperation in

Africa (CSSDCA).

1.3.2- AU conflict intervention framework: the African

Peace and Security Architecture

The main AU mechanism for promoting peace and security is the

African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA). It consists of evolved

instruments or elements for conflict prevention, management and resolution in

the continent. The architecture is comprehensively outlined in the Protocol

relating to the establishment of the Peace and Security Council of the African

Union. The Peace and Security Council (PSC) which is the hub of the APSA was

established pursuant to Article 5(2) of the Constitutive Act of the AU, as a

collective security and early warning arrangements to facilitate timely and

efficient response to conflict and crisis situations in Africa.

The Constitutive Act and the PSC Protocol gives the AU the

power to create the structures and processes necessary for the establishment of

a comprehensive Peace and Security Architecture for the Continent. The

institutional structures of APSA include the Peace and Security Council (PSC),

the African Union Commission, the Common African Defense and Security Policy,

the Military Staff Committee (MSC), the Panel of the Wise (PoW), the

Continental Early Warning System (CEWS), the African Peace Fund (PF), and the

African Standby Force (ASF). However, six of these - the PSC, AUC, PoW, CEWS,

PF and the ASF - constitute the main pillars of APSA as explained below.

14

The Peace and Security Council (PSC)

The PSC is the AU's standing decision-making organ for the

prevention, management and resolution of conflicts (PSC Protocol, Art. 2(1))

and the cornerstone of the APSA. The Council is composed of 15 members elected

on the basis of equal rights, 10 members elected for a term of 2 years, and 5

members elected for a term of 3 years in order to ensure continuity. With this

regard, article 7 of the PSC Protocol, stipulates that the PSC, in consultation

with the chairperson of the AU Commission, is mandated precisely to:

- Anticipate and prevent disputes and conflicts, as well as

policies that may lead to genocide and crimes against humanity;

- Undertake peace making and peace building functions to

resolve conflicts where they have occurred;

- Authorize the mounting and deployment of peace support

missions;

- Intervene on behalf of the AU in a member state's conflict

under grave circumstances, namely those involving war crimes, genocide, and

crimes against humanity, as defined in relevant international conventions and

instruments;

- Institute sanctions whenever an unconstitutional change of

government takes place in a member state, as provided for in the Lomé

Declaration;

- Implement the common defense policy of the African Union;

- Follow-up on the progress made towards the promotion of

democratic practices, good governance, the rule of law, protection of human

rights and fundamental freedoms, respect for the sanctity of human life, and

the upholding of international humanitarian law by member states; and

- Support and facilitate humanitarian action in situations of

armed conflicts or major natural disasters (PSC Protocol, 2003).

The PSC in conjunction with the Chairperson of the AU

Commission may authorize the mounting and deployment of peace support

missions.

The African Union Commission (AUC)

The AUC is responsible for the implementation of PSC decisions

and provides operational support. This happens mainly through the AU Commission

Chairperson and the AU Commissioner for Peace and Security, who report to the

PSC on the implementation of PSC decisions and their own initiatives. The

Chairperson and Commissioner are supported by the Peace and Security Department

(PSD).

The AU Commission also provides strategic, political,

technical, and planning support to operations authorized by the Peace and

Security Council and carried out by regional coalitions of Member States,

Regional Economic Communities (RECs), or Regional Mechanisms for Conflict

Prevention, Management and Resolution (RMs).

15

The Panel of the Wise (PoW)

The PoW was constituted under the terms of Article 11 of the

PSC Protocol, to support the efforts of the Council and those of the

Chairperson of the commission, particularly in the area of conflict prevention.

It comprises 5 members drawn from various segments of society of AU Member

States.

The Continental Early Warning System (CEWS)

The CEWS is to provide timely and reliable data to warn the

PSC and the AU Commission of potential conflicts and outbreaks of violence to

enable the development of appropriate response strategies to prevent or resolve

conflicts in Africa. The Committee of Intelligence and Security Services in

Africa (CISSA) compliments the CEWS. The Committee was established on 26 August

2004 in Abuja, Nigeria by Heads of Intelligence and Security Services of

Africa. The CEWS coordinates efforts where possible with similar structures in

the RECs.

The African Peace Fund (PF)

Established by the PSC Protocol, the PF provides financial

resources for the AU mandated Peace Support Operations (PSO) as well as other

operational activities related to peace and security. This is premised on

Article 21 (2) of the Protocol. The Peace Fund is supposed to be funded through

contributions from donors, member states, private sector, civil society and

individuals. During its summit in Addis Ababa in 2010, the African Heads of

State agreed to increase the Peace Fund from 6 per cent to 12 per cent of

assessed contribution of member states on incremental basis of 1.5 per cent per

annum until the 12 per cent is achieved. Other changes are to be implemented in

the coming years.

The African Standby Force (ASF)

The ASF was established by the provisions of Article 13 of the

PSC Protocol. A Policy Framework establishing the ASF and the Military Staff

Committee (MSC) was adopted in May 2003 by the 3rd Session of African Chiefs of

Defense Staff. In March 2005, the AU Commission and RECs/RMs met in Addis Ababa

and adopted a Roadmap for the Operationalization of the ASF. The force is

organized into five multidisciplinary brigades (military, civilian and police

elements) on the basis of the five AU regions, and the Regional Economic

Communities or Mechanisms.

The Roadmap also emphasized the establishment of planning

structures at the regional level: ASF Planning Elements (PLANELMS) and the

formulation of key policy documents at the strategic level. The documents are

on Doctrine, Logistics, Training and Evaluation, Standard Operational

Procedures (SOP), Command, Control and Communication Systems. Collectively, the

5 Regional Brigades will provide the AU with a combined standby capacity of

about 15,000 to 20,000 troops trained in peace operations ranging from

low-intensity observer mission to full-blown military intervention. The

RECs/RMs such as the SADC, the ECCAS, ECOWAS and IGAD are continuously involved

in the process of establishing and running their respective brigades. For

instance, the ECOWAS Monitoring Group Integral to this architecture also, is

the Common African Defense and Security Policy (CADSP)

16

and the Military Staff Committee (MSC). The CADSP adopted in

2004 is to ensure Africa's common defense and security interests and goals as

set out in Articles 3 and 4 of the Constitutive Act. The MSC is an advisory

organ of the PSC, and consists of 15 military experts from the PSC member

states who are resident in Addis Ababa.

Moreover, in 2008, a Memorandum of Understanding on

Cooperation in the Area of Peace and Security was signed between the African

Union, the Regional Economic Communities and the Coordinating Mechanisms of the

Regional Standby Brigades of Eastern Africa and Northern Africa (hereafter the

2008 Memorandum). The 2008 Memorandum between the AU and REC/RMs is the legal

basis of the coordination between the AU and REC/RMs in the operationalization

of the APSA. Its objective is to «contribute to the full

operationalization and effective functioning of the African Peace and Security

Architecture» (Article II, para 2(i)).

1.3.3- AU principles in conflict intervention

There are certain minimum principles that guide these

institutions and sub institutions of AU in conflict

resolution. Article 4 of the Constitutive Act of AU outlined the

basic principles of operation for the

organization. Some of these principles include:

- sovereign equality and interdependence among Member States of

the Union;

- respect of borders existing on achievement of independence;

establishment of a common

defense policy for the African Continent;

- peaceful resolution of conflicts among Member States of the

Union through such appropriate

means as may be decided upon by the Assembly;

- prohibition of the use of force or threat to use force among

Member States of the Union;

- non-interference by any Member State in the internal affairs of

another;

- the right of the Union to intervene in a Member State pursuant

to a decision of the Assembly in

respect of grave circumstances, namely: war crimes, genocide and

crimes against humanity;

- the right of Member States to request intervention from the

Union in order to restore peace and

security;

- respect for democratic principles, human rights, the rule of

law and good governance;

- promotion of social justice to ensure balanced economic

development;

- respect for the sanctity of human life, condemnation and

rejection of impunity and political

assassination, acts of terrorism and subversive activities and

condemnation and rejection of

unconstitutional changes of governments (AU Constitute Act,

2002).

17

1.3.4- AU methodological approach in conflict

intervention4.

The AU and RECs in the frame of the APSA, consider four types

of interventions including the diplomatic interventions, the mediation, the

peace support operations (PSOs), and the Post-Conflict Reconstruction and

Development (PCRD) activities.

Diplomatic interventions

The diplomatic interventions include a wide array of

activities and decisions ranging from holding meetings on the conflict

situations at various political levels, to varying levels of diplomatic

statements, to taking actions such as setting up high-level panels and adopting

sanctions. Diplomatic interventions are undertaken by a whole range of actors

by both the AU and REC/RMs.

Mediation efforts and preventive diplomacy

As part of the mission of the PoW, mediation efforts are

understood as ranging from establishing mediation teams, organizing

consultations between parties, and reaching an intermediate or final peace

agreement. The PoW also undertake all the efforts of preventive diplomacy in

countries where violence has not erupted yet or might erupt in the near future.

Preventive diplomacy presumably takes place before conflicts escalate, and

before AU and REC/RMs become more visibly engaged (AU PoW retreat report,

Ouagadougou 2012).

Peace support operations (PSOs)

A third important set of activities center around PSOs

including activities around the authorization, deployment and maintenance of

PSOs. Activities analyzed under this type of instrument range from convening of

a resource mobilization meeting, to authorizing or mandating the deployment of

a peace support operation, deploying a peace support operations or extending a

mandate. Moreover, in areas of deployment of AU Peace Support Operations, there

are engagements geared towards developing and implementing Quick Impact

Projects (QIPs) and Peace Strengthening Projects (PSPs).

Post-conflict Reconstruction and Development (PCRD)

The PCRD include all the initiatives and efforts of the AU and

REC/RMs under the APSA to support countries weak or post conflict countries for

their reconstruction and development to avoid them relapsing in conflicts. For

instance, in the context of post-conflict reconstruction and support of

countries, the AU Commission deploys mission to assess the priority needs of

the country in need. These include identification of joint activities in

support of implementation of peace agreements in Member States emerging from

conflict; conducting needs assessment missions; consolidating and scaling up

security sector reform and disarmament, demobilization and reintegration

initiatives; technical and

4 The methodology was developed by ECDPM and GIZ

and reviewed in 2016 by IPSS in collaboration with AU Commission.

18

operational support to control the illicit proliferation of

small arms and light weapons, and sustained collaboration with RECs/RMs and

civil society organizations.5

1.4- Literature review

There is a substantial amount of literature dealing with the

historical, socioeconomic, and political background of the conflict in Mali

from various angles. Moreover, the intervention in 2012 by the AU and ECOWAS in

Mali have been the subject of some publications by think tanks and have been

also taken up in academic discussions to some extent.

All the scholars interested by Mali conflict admit that the

crisis is the culmination of many interlinked factors and triggers out of which

has emerged a very complex image in which many interests are at stake. However,

there are different ways studies approach the conflict depending on which

issues they focus more.

Not ignoring other factors, many studies lay more emphasis on

the historical background of the Tuareg rebellions and the way they are

believed of not having been well addressed by the Malian successive

governments. For instance, as early as 2011, (Emerson, (2011) provided an

in-depth examination and analysis of the 2006-2009 Tuareg rebellion in Mali and

Niger. He identifies the underlying reasons behind the rebellion, explores

contrasting counter-insurgency (COIN) strategies employed by the two

governments, and presents some lessons learned. From his analysis, it appears

that while both COIN approaches ultimately produced similar peace settlements,

the Malian strategy of reconciliation combined with the selective use of force

was far less effective than the Nigerien iron fist approach at limiting the

size and scope of the insurgency and producing a more sustainable peace. The

author was then able to forewarn about the risk of another insurgency in Mali

in the near future.

Cline (2013) also views the conflict in Mali through the lens

of the Tuareg ill addressed rebellions. In his study, he analyses the

historical background of rebellions and argues that although each of these

rebellions was ended by a cease-fire, the Malian government never succeeded in

instituting longer term peace agreements. This situation combined with an

almost complete security vacuum in northern Mali on the part of the government,

led to the 2012 Tuareg rebellion which presented even more significant security

threats marked by multiple armed groups - Tuareg rebels, Islamists, and local

militias - with multiple competing agendas and with a pattern of varying levels

of cooperation and conflict. The author warns that the intractable environment

will be very difficult to resolve in the long term even with external

intervention. He further fears that the focus on counterterrorism which is in

reality a much more complicated security environment in northern Mali, may turn

short.

Moreover, even if Zounmenou (2013) recognizes the role of the

Libyan crisis as a factor which left the regional security environment depleted

and created conditions conducive for the proliferation of, and

5 Main successes of the AU in Peace and Security,

challenges and mitigation measures in place,

https://au.int/sites/default/files/pressreleases/31966-pr-main_successes_of_the_au_in_peace_and_security.pdf,

accessed on June 12, 2018

19

attacks by, radical religious armed groups in the northern

regions of the country, he stresses on the Tuareg armed movement: the National

Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA). For him, far from being a new

phenomenon, the Tuareg-led armed insurrection in the northern regions is as old

as the post-colonial Malian state, and continues to pose tremendous challenges

in West Africa and the Sahel region for both regional and extra-regional

actors. He further recalls that while attention is predominantly focused on

defeating the jihadist groups that have threatened the survival of the Malian

state, one must not lose sight of the fact that the `Tuareg Factor', as

represented by the rebellion launched by MNLA, remains critical both in terms

of appreciating the deterioration of the situation and attempting to frame

long-lasting solutions. The author adds that the Tuareg's persistent recourse

to rebellion against Bamako needs to be understood within a historical

trajectory that takes into consideration three key parameters: firstly, the

post-colonial state in Mali and its African leadership's relations with the

descendants of the Tuareg communities; secondly, the amalgamation created by

the so-called war on terror; and, finally, the contradictions of the

democratization process of the 1990s.

Thurston and Lebovich (2013) provide resources that help

explain and contextualize the intersecting crises that destabilized Mali in

2012-2013. Part of their analyses are related to the rebellion by Tuareg

separatists. They argue that the MNLA's rebellion, like other Tuareg-led

uprisings before it, reflected long-held grievances and bitter historical

memories among some Tuaregs. The study reveals that fighters in 2012 - in some

cases the same men who had fought the Malian army in 1990 and 2006, or whose

fathers had fought in 1963 - felt that postcolonial Mali had marginalized and

victimized them. The MNLA dreamed of founding an independent state,

«Azawad,» comprising the northern Malian regions of Gao, Kidal, and

Timbuktu. They further explain that even before the rebellion broke out, a

confluence of problems, ranging from longstanding communal grievances to

official corruption and complicity in drug smuggling and perhaps militant

activity as well, had weakened the Malian state.

Furthermore, some other scholars view the conflict in a

regional context characterized by the Arab Spring, the fall of Qaddafi and the

rise of Islamism. This is the example of Shaw (2013) who examined the

commonly-assumed notion that the Libyan Civil War generated the current

conflict in Mali. The author applied the causal mechanisms from the theories of

escalation and diffusion/contagion to the Libya-Mali case, to determine if such

a link can be made. Using Lake and Rothchild's (1996) framework, the study

found that, with some modifications to include non-state actors, mechanisms

from both theories were at play in this case. He came to a conclusion that

conflict in Mali did occur as the result of escalation and diffusion/contagion

mechanisms from the Libyan Civil War. Arieff6 (2013) also outlines

how the spread of state fragmentation amidst the Arab Spring, combined with

«the spread of violent extremist ideology» facilitated the

entrance of three violent extremist groups into Mali: Al Qaeda in the Islamic

Maghreb (AQIM), Ansare Dine (of Tuareg origin), and the Movement for Unity and

Jihad

6 Alex Arieff, analyst in African Affairs for the

US Congressional Research Service, in his January 14, 2013 report for Congress

titled, «Crisis in Mali».

20

in West Africa (MUJAO); each of these groups having links

between extremists, drug trafficking, and smuggling networks. She further to

state that the collapse of the Libyan state in 2011 created a vacuum with

thousands of «core combatants . . . with relatively sophisticated

equipment obtained from Libya» who moved southwards into Mali and

«imposed harsh behavioral and dress codes on local residents in the

north»

Another researcher with the same view is Yehudit (2013). His

study examines the relatively unknown issue of the ethno-political and

strategic partnership that existed between the Libyan regime of Muammar

al-Qaddafi and the ethnic Tuareg minority of Sahelian origin, with an emphasis

on the period during 1990-2011. The author argues that during that period many

Tuareg for various reasons migrated to Lybia where they were mainly enrolled in

the army. However, the ramifications of the `Arab Spring' and the subsequent

fall of Qaddafi's regime put an end to the unique partnership. Many Tuareg then

fled the chaos of post-Qaddafi Libya and returned to their native countries

heavily armed, disrupting the sensitive ethnic and political balances in the

Sahel belt.

For Utas (2012), the events in Mali were the first major

incidents in the post-Qaddafi political landscape and in the power vacuum in

the Sahel region as positions in the Malian political game have shifted partly

due to the return of «new recruits and military personnel from within a

North Malian diaspora in Libya, typically from within the army». He also

notes that an important aspect in the conflict is the drug route, an illicit

business likely to involve actors from rebel movements, the army and the

government in Bamako and unravelling the linkages among these actors could be

informative.

Ellis (2013) goes further to link the crisis in Mali to the

general context in the Sahel. His analysis touches on nomadism and mobile

populations in connection with Islamism and political Islam. Ellis views the

wider Sahel as a borderland with mobile populations. He argues that North

Africa and Sahara by 2012 were «marked by a series of political

transitions in which debates and struggles within Islam are central».

Ellis believes that what happens in northern Mali is linked to what happened in

Egypt. According to him these movements are trying to renew their societies

through political Islam and that is why «many evolving disputes in

north Africa and the Sahara fuse religious language and political impulse to

powerful effect». For him, it is important to consider the spatial

dimensions of the conflict as there is a connection to what happens in the

wider Sahel region, particularly given the history of the nomadic people of the

Sahara.

In the same line, Pejic (2017) thinks that although

historical, social and economic issues have their impact in the perpetual

cycles of rebellion in Mali, there are also other more important factors which

caused the 2012 crisis in the country. He argues that the presence of radical

groups in Sahel is a decade long issue for all regional governments and with

the collapse of the Libyan state during the Arab Spring the Jihadists gained

momentum in the region. The threat of radical Islamism was evident in Algeria,

Tunisia, Libya and Mali. In Mali most of these armed groups were stationed in

the northern part of the country, and there are a couple of reasons behind

including the harsh terrain of northern Mali limiting the region's

accessibility thus allowing the groups to settle and establish camps and

networks. Other

21

reason raised is the large and porous border with Algeria

which makes it easy to smuggle weapons, drugs or other illicit goods. The last

issue is the wide discontent among citizens in northern Mali which is often

used by these organizations to recruit new members or spread their

influence.

Besides, several other works see the conflict in Mali as a

result of a whole State failure in different sectors that were not perceived or

purposely hidden during years. For example, Bøas (2013) argue that the

myth about Mali was that it was a democratic state. For him, while Mali was a

poster child for democracy and governance reforms in West Africa, the war in

the North, Islamists, the drug trade, a military coup, and a political crisis

in Bamako illustrated the falsity of this story. He believes that the myth was

created by international organizations, bilateral donors, NGOs and the Malian

state, all having their own motives for portraying Mali as a success. He

further argues that the reforms stemming from the National Pact in 1992

including political democratization, economic liberalization and administrative

decentralization simultaneously operated in a very weak State, were doomed to

failure, because these reforms were hijacked by an alliance of regional

power-holders in the north and the political elite in Bamako, resulting in

corruption and a blind eye being turned as long as profits could be made.

Bøas adds that this context allowed AQIM and other Islamist groups to

thrive in the north and to open the country to trade and trafficking in drugs

and arms. For the author this situation also created a dysfunctional Malian

army, which eventually staged the coup d'état and opened up the north to

Islamist influence when Tuareg fighters returned after the fall of Qaddafi with

plenty of weapons and ammunition.

In a report of Norwegian peacebuilding resource center

(NOREF), Francis (2013), points out that even before the outbreak of the Malian

crisis, northern Mali had become a breeding ground and safe haven for diverse

groups of jihadists and militants led by AQIM. These groups not only exploited

the fundamental grievances of the local population against the government of

Mali and its repressive military and security forces, but also organized

sophisticated criminal enterprises that involved drug and human trafficking,

arms and cigarette smuggling, and the kidnapping of Western nationals for

ransom. These criminal enterprises became valuable sources of funding and were

profitable for all stakeholders, including corrupt Malian government officials,

state security agencies, local leaders, separatist rebels and Islamist

extremists. These Sahelian criminal enterprises and their profitable economic

and financial opportunities made jihadi insurgency a lucrative economic

activity. 7

Boukhars (2013) also discussed the political economy of war,

power balances, and the regional political marketplace and came to the

conclusion that weak and corrupt state institutions, ethnic tensions and

competition over scarce resources are part of the main root causes of the

conflict in Mali. He advises to

7 Norwegian peacebuilding Resource Center, «The

regional impact of the armed conflict and French intervention in Mali», a

report by David J. Francis, p4, NOREF,

http://www.operationspaix.net/DATA/DOCUMENT/7911~v~The_regional_impact_of_the_armed_conflict_and

_French_intervention_in_Mali.pdf, accessed on June 12, 2018

22

avoid a simplistic consideration of the conflict viewed solely

through the lens of Islamic radicalization or as a north-south dispute.

In his analysis of the conflict, Marchal (2012) summed up that

the crisis in Mali was born out of a combination of factors, including decayed

state institutions and practices, a collapsed military force and a system of

governance built on patronage, not democracy. He explores the background to the

crisis and argues that while the war in Libya was the trigger, the crisis is

long-term and several aspects lie behind it. He identifies four dynamics that

led to the military coup of March 2012: «the debatable implementation

of previous peace settlements with Tuareg insurgency; the growing economic

importance of AQIM activities in the Sahelian region; the collapse of the

Qaddafi regime in Libya; and the inability or unwillingness of Algeria to play

the role of regional hegemon now that its rival (Libya) has stopped doing

so».

Lecocq et al. (2012), a group of eight scholars, gave a

comprehensive background and analysis to the 2012 onward political crisis in

Mali in two key points. First, with regard to the international and Saharan

dimensions of the conflict, the scholars argue that even though via actions

they took or refused to take, Mali's neighbors and other foreign powers made

the crisis a regional one, all the roots of the crisis were first and foremost

Malian. According to their analysis, the wounds of the North which re-opened in

the 1990s, had long remained unhealed on the Malian body politic. For them,

this sore had been further infected in recent years by passive or active

participation in the drug trade by high-ranking military officers and political

figures, by Bamako's laissez-faire attitude to those in the north it considered

its political proxies, and by its failure to counter the presence of foreign

Mujahideen and their local recruits. They also observe that while the problems

plaguing the north have been relatively visible for several years, outside

observers failed to diagnosis the hippo's (Mali) internal ailments, especially

the degree of corruption pervading a political system in which many of them

were deeply invested. The fall of the Touré government in just a few

days in March - an event welcomed by many Malians - can only be explained by

mounting dissatisfaction during Touré's second term in office, combined

with a real lack of faith in the democratic process represented by the

cancelled April elections.

Second, for any real understanding of the complex crisis, the

scholars recommend to look simultaneously out from the Sahara and up from

Bamako. For them, «any analysis should be concurrently attentive to

regional and international factors at work in the Sahara and aware of the

deeply local, even personal nature of the political crisis there, and in Kidal

and Timbuktu in particular».

Apart from these works analyzing the Mali armed conflict,

there have been some few academic discussions related to the African Union and

ECOWAS intervention in the conflict.

For instance, Aning & Edu-Afful (2016) observed that both

the African Union (AU) and the Economic Community of West African States

(ECOWAS) have been global leaders in embracing and operationalizing

Responsibility To Protect (R2P). They argue that the adoption of the AU's

Constitutive Act, Article 4 (h) in 2000, has transformed its old-fashioned

principle of noninterference to one of

23

nonindifference. This authorizes the AU to intervene in Member

States with respect to war crimes, genocide, ethnic cleansing, and crimes

against humanity. As for ECOWAS, it has through its conflict prevention,

management, and resolution protocol and its conflict prevention framework

deepened and practicalized the notion of sovereignty as responsibility. These

frameworks from both the AU and the ECOWAS have close similarities to the

Responsibility To Protect (R2P) norms. But the authors regret that although

these notions are captured in official documents, their actual

operationalization faces challenges relating to sovereignty, limited

institutional capacity, a restricted appetite for enforcement action, and a

lack of explicit instruments to activate their intervention clauses in R2P-like

situations. In spite of these challenges, the article argues that the

initiatives of both the AU and the ECOWAS in Mali, Cote d'Ivoire, and Libya

demonstrated a positively active African agency in contributing to global peace

processes.

Cocodia (2015) argues that the jihadists' actions prompted

international intervention in the Malian crisis, with the Economic Community of

West African States (ECOWAS), the African Union (AU), France, the United

States, and the European Union (EU) playing pivotal roles to stem the country's

slide into civil war and anarchy. The author focuses on the AU who began

playing an active role in June 2012, later upgrading the mission from a

regional to a continental one and leading to the creation by the United Nations

of the African-led International Support Mission in Mali (AFISMA). He observes

that AFISMA was originally supposed to be drawn from the Western African

Standby Brigade (WASB), which is the African Standby Force (ASF) brigade in

West Africa. However, the AU since 2002 has been trying to get the ASF up and

running. Yet it unfortunately exists more as a concept - a «paper

tiger» - than a fully operational facility. Had it been operational during

the crisis in Mali, it would have been deployed in Mali.

According to Gain (2018), the African Peace and Security

Architecture (APSA), the African Union's (AU) set of tools for the maintenance

of peace and security, would seem the obvious mechanism for resolving crises in

countries beset by violence, such as Mali. The five main organs that comprise

the AU peace and security architecture were intended to systematically address

threats to peace and security at various levels, and to complement and

reinforce one another. However, the author realizes that this has not been the

case. He argues that though the AU and ECOWAS laid the groundwork for a UN

Security Council Resolution in late 2012 which authorized a military

intervention known as the African-led International Support Mission in Mali

(AFISMA), the swift deployment of the French military forces and its early

military successes raised questions about the AU's and ECOWAS's capacity to

manage such peace-support operations due to their lack of logistical readiness