UNIVERSITY OF RWANDA

COLLEGE OF

BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS

SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS

DEPARTMENT

OF APPLIED STATISTICS

IMPACT OF ONE CUP OF MILK PER CHILD PROGRAM ON SCHOOL

DROPOUT IN HUYE DISTRICT

Dissertation submitted to the College of

Business and Economics In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the award

of bachelor's Degree in Applied statistics.

Presented by: FABRICE Birasa

Registration Number: 12114403

SUPERVISOR: Dr DIEUDONNE Muhoza

Done at Huye on 8th May,

2015

DECLARATION

I, FABRICE Birasa, a student at University of Rwanda, COLLEGE OF

BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS, School of Economics, Department of applied statistics

hereby declare that the presented dissertation: «The Impact of one cup of

milk per child program on school dropout level». A case study of Huye

district primary schools» is my own presentation which has not been

presented for any other academic purpose at any University or higher learning

institution.

Date: ........June, 2015

Signature ............................

FABRICE Birasa

CERTIFICATION

I certify that this research on «The Impact of one cup of

milk per child on children dropout; A case study of Huye district primary

schools» presented by FABRICE Birasa. The research was done towards

partial fulfillment of Bachelor's Degree submitted to College of Business and

Economics, School of Economics, department of applied statistics is based on

the original research and the study under the supervision of Dr DIEUDONNE

Muhoza

Date......June, 2015

Superior's Signature:..........................

Supervisor: Dr DIEUDONNE Muhoza

DEDICATION

To Almighty God

To all my lectures

To all my family members

To all my colleagues and friends

DEDICATION

I dedicate this dissertation:

MAY GOD BLESS YOU

ALL!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The following work is not only an individual work .I could never

have accomplished it without help, support, guidance and efforts of a lot of

people to whom I owe my thanks. I would like to gratefully and sincerely thank

all individuals who helped me during my education career, financial support,

encouragement, moral support, all my family, friends all kinds of your advice,

moral, love have contributed towards the successful accomplishment of this

work.

I would like to extend my sincere gratitude and heart-felt

appreciation firstly, to my Almighty God in Christ Jesus name, to whom I owe my

life, wisdom, and good faith in my whole life. I praise him for enabling me

throughout my academic journey and carry out this academic research in

particular.

Special thanks go to Dr DIEUDONNE Muhoza my Supervisor, whose

guidance, encouragement and correction for this study has inconsiderably

contributed towards its achievement.

I would like also to acknowledge my beloved sister and brothers:

BIRASA (Claire, Germain, Benoit, Tresor, Eric, Bruno and last born of my family

Genau); your support towards my academic performance is immeasurable.

Institutionally, I would also like to thank the Government of

Rwanda for its scholarship granted to me to the extent that I am completing my

bachelor degree courses. I am grateful for the opportunity to study in the

University of Rwanda.

My gratitude also goes to all classmates with whom we shared

academic ideas for whole these four years of undergraduate.

Acknowledgement again is attributed to UR-Christian communities'

members, specifically CEP-UR HUYE CAMPUS, ELAYO CHOIR, SGM, etc.

Finally, thanks goes to my relatives whose names did not appear

above and friends in one way or another towards the successful completion of

this work.

LIST OF ACRONYMS ND

ABBREVIATIONS

MDGs: the Millennium Development Goals

EFA: Education for all

UNESCO: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural

Organization

WHO: World Health Organization

MoH: Ministry of Health

CJM: Center des Jeunes muet

MINEDUC: Ministry of Education

MINAGRI: ministry of agriculture

WHO: World Health Organization

UNICEF: United Nations Children's Fund

MINALOC: Ministry of Local government

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

DECLARATION

I

CERTIFICATION

II

DEDICATION

III

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

IV

LIST OF ACRONYMS ND ABBREVIATIONS

V

TABLE OF CONTENTS

VI

LIST OF TABLES

IX

LIST OF FIGURES

X

ABSTRACT

XI

CHAPTER I : GENERAL INTRODUCTION

1

1.1 Background of the study

1

1.2 Statement of the Problem

2

1.3 Research Objective

3

1.3.1 General Objective

3

1.3.2 Specific Objective

4

1.4 Research Question

4

1.5 Research Hypothesis

4

1.6 Significance of the study

4

1.7 Scope of the study

5

1.8 Organization of the study

5

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW

6

2.1. Introduction

6

2.1.1 Definition of key terms

6

2.1.2 Dropout

9

2.2 The literature related to causes of Dropout

9

2.2.1 School level factors

10

2.2.2 Household (family) level factors

11

2.3 The relating to consequences of school dropout

and strategies to be taken

13

School and Community Perspective

15

2.4 Summary of the literature review

19

CHAPTER THREE: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

20

3.1. Introduction

20

3.2. General Description of the study

20

3.2.1. Research design

20

3.2.2. Purpose of the study

21

3.2.3. Study process

21

3.2.5. Outcome of the study

21

2 .3 Conceptual framework

21

3.4 Geographical location of huye

district

23

3.5 Population study, Sample size and Sampling

techniques

24

3.5.2 Sampling design

24

3.5.3 Sample size determination

25

3.6. Description of the instruments of data

collection

25

3.6.1. Questionnaire

25

3.6.2. Interview schedule

25

3.6.3. Documentation

26

3.7. Data Processing and Analysis

26

3.7.1. Coding

26

3.7.2. Editing

26

3.7.3. Tabulation

26

3.8 Methods of data analysis

27

3.8.1 Descriptive statistics

27

3.8.2 Multivariable analysis

27

3.9. Limitation of the Study

30

CHAPTER FOUR: DATA ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION

31

4.1 Introduction

31

4.2. Profile of respondents:

31

4.2 Results from the percentage distribution of

respondents by the level of dropout

32

4.3 Descriptive statistics of causes of dropouts by

the level of dropout

34

4.3.1 Distance from school

35

4.3.2 Parents' illiteracy

35

4.3.3 Child's Family poverty

35

4.3.4 One cup of milk per child

35

4.3.5 Failure or repetition of children

36

Source: primary data

39

4.4 Results from bivariate analysis using

chi-square test

39

REFERENCE

46

APPENDIX

49

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1 Table showing the current distribution of

milk among children of primary schools of Huye.

7

Table 2 Cost and Funding mechanism of one cup of

milk per child countrywide

8

Table 3 Sample selection

25

Table 4 Percentage distribution of respondents by

the level of dropout

32

Table 5 Percentage distribution of respondents by

factors affecting dropout

33

Table 6 Percentage distribution of factors

affecting dropout by the level of dropout

34

Table 7 Chi- square test table illustrating

association between level of dropout and its factors

40

Table 8 Parameter estimates for multinomial

logistic model

42

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1 Figure showing children having milk at

their disposal in Nyanza district

8

Figure 2 Conceptual Framework between Level of

dropout and factors affecting it

22

Figure 3 Geographical location of Huye district

23

Figure 4 Distribution of respondents by their

education level and Gender

32

Figure 5 Distribution of respondents to whether the

school has the program or no by the level of dropout.

36

Figure 6 Figure showing the distribution of

consequences to child's family by the level of dropout

37

Figure7 Distribution of respondents to the

consequences to school against the level of dropout.

38

Figure 8 Distribution of respondents regards

consequences of dropout to a country by the level of dropout.

39

ABSTRACT

To study the Impact of one cup of milk per child on children

dropout, the following objectives were set: To identify the causes associated

with children drop out of primary schools in Huye district. To examine the

relationship between one cup per child and dropout in Huye district, to find

out the challenges associated with children dropout in Huye district, to find

out strategies to be taken in order to solve challenges of Children dropout in

primary school in Huye district. Questionnaire, interview and observation were

used to collect data from survey of population consist of 98 primary schools

out of which 4 primary schools were selected namely Butare Catholic primary

school, Cyarwa primary school, Rango primary school, and CJM whereby a sample

of 60 respondents were selected by using purposive sampling technique as well

as simple random sampling, the researcher used secondary.

All The data were analyzed by using SPSS 16 (as a statistical

package for analysis) and interpreted by using tables, figures and charts as

well as excel was used during the graphical presentation of results. The

findings revealed that the one cup of milk per child contributed towards the

reduction of dropout within primary schools.

After analyzing and interpreting the data, recommendation and

suggestions on what measures are to be taken by policy makers, specifically

leaders in charge of education system as well as researchers were highlighted

for the reduction of dropout.

CHAPTER I : GENERAL

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background of the

study

Education is as important and very essential to man as life

itself on this world, in fact it is a very important means of developing any

nation (Haki Elimu, 2009).

«It is through education that the daughter of a peasant

can become a doctor; that a son of a mineworker can become the head of the

mine; that a child of farm workers can become the president of a great

nation» (Nelson Mandela)

The term education has not lent itself to any strict

consensual definition as it depends on the perspective from which one views it,

it can be considered as the process of acquiring knowledge, skills, factors,

interest, abilities, competence and the cultural norms of a society by people

to transmit this life to the coming generations so as to enhance perpetual

development of the society (Okoro, 1998)

In spite of the importance attached to education both

nationally and internationally, Education sector in the world still is facing a

lot of problems that varies from one country to another such as poor Academic

performance, School dropout, Truancy, Poor environment of learning and other

social and economic problems relating to education (Rumberger, 2001).

School dropout in its simplest meaning is the untimely

withdrawal from school, these students who withdraw from school prematurely end

up not obtaining any certificate of graduation (Wotherspoon2004; Bridge land et

al., 2006; Oghuvbu, 2008).

The prevalence of drop out varies between and within countries

and occurs more frequently in certain age ranges and grades (depending on the

educational structure and patterns of participation in that country).

The student's decision to drop out of schools has a long

term consequences that can contribute to juvenile delinquency, welfare

dependency or in the worst cases. There is general consensus that the school

dropout problem has reached epidemic proportions internationally and has become

a global problem confronting the education industry around the world (Patrick

2008; Wotherspoon2004; Bridge land et al., 2006; Oghuvbu, 2008).

In African countries, dropout is a significant problem and is

associated with socio-economic and socio-cultural background and geographical

factors, Studies in Nigeria reveal that financial constraints are among other

things the main reasons for school dropout (Okoje, et al-1996) as fathers and

mothers are mainly responsible for costs of children's education.

1.2 Statement of the

Problem

Education plays a vital role in human resources development.

Schooling, according to the human capital theory, is an investment that

generates higher future income for individuals. It elevates the productivity

and competence of individuals and thus produces skilled manpower that is

capable of leading the economy towards the path of sustainable economic

development.

Strengthening the quality of education has become a global

agenda at all educational levels and more so at the primary level. Quality

primary education also ensures increased access and equality and it is mainly

due to these reasons that various international Forums and Declarations have

pledged improvements in quality of primary education. It was stated in a

report of Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 1991) that

dropout phenomenon is a world-wide problem associated with the process of

development in any society whether such society is a developing or developed

nations. For instance, in the United States, a federal study group known as the

National Commission on Excellence in Education observed critically that high

school dropout rate rose to almost 30% by the late 1980s. In the light of the

Annual Education for All Global Monitoring Report, published by UNESCO, it has

been revealed that Nigeria, Pakistan, India, and Ethiopia, account for 23

million out of the world`s 77 million out off-school children. There are many

differences between the education systems of developed and developing

countries.

According to the World Food Programme, 66 million primary

school children go hungry every day, with 23 million hungry children in Africa

alone. Furthermore, 80 per cent of these 66 million children are concentrated

within just 20 countries. Additionally, 75 million school-age children (55 per

cent of them girls) do not attend school, with 47 per cent of them living in

sub-Saharan Africa. Thus, the need to reduce hunger while increasing

school enrollment in these children is evident, and school feeding programmes

have been developed to target this multi-faceted problem.

Although Rwanda has sustained a strong political commitment to

improve education access and quality, placing the country on a planned

trajectory towards achieving quality basic education for all, the country is

far from reaching the goal of universal primary education, with only half the

children completing primary school. (EFA country profile 2012)

Drop out is an under-researched area, even though the problem

is prevalent. With EFA and MDGs targeting access to education, knowledge around

dropouts and studies such as this, can help illuminate some of the complexities

around dropping out and bring new insights to policy makers and educational

practitioners. By understanding dropout further there will be greater potential

to move towards a more meaningful notion of access. (Frances Hunt, May 2008)

The government of Rwanda has started, around 2010, the program

entitled one cup of milk per child dedicated to decrease malnutrition, as well

as dropout, among children in Rwandan primary schools.

The «One Cup of Milk Per Child programme has been

introduced in around 100 schools in Rwanda and is being expanded in

collaboration with MINAGRI.

This study is important because it brings together a range of

literature on dropout causes and its effects in a way that has not happened

before and discusses the possible influence that one cup of milk per child can

bring on children dropout.

1.3 Research Objective

1.3.1 General Objective

The main objective of this study will be to examine the Impact

of one cup of milk per child on children dropout in Huye district.

1.3.2 Specific Objective

The specific objectives of the research will be the

following:

1. To identify the causes influencing primary school dropout

in Huye district.

2. To examine the relationship between one cup of milk per

child and school dropout level in primary schools of Huye district.

3. To find out the consequences associated with school dropout

in Huye district.

1.4 Research Question

1. What are the causes of children dropout in primary schools

of Huye district?

2. Is there any relationship between one cup of milk per child

and dropout in Huye district?

3. What are the consequences associated with children dropout

in Huye district?

1.5 Research Hypothesis

In this study, the following hypothesis will be tested:

H0: There is no relationship

between one cup of milk per child and school dropout

H1: There is a relationship

between one cup of milk per child and school dropout

Assumptions

1. Children that are likely to dropout are those without

access to one cup of milk per child program.

2. One cup of milk per child can help to reduce children

dropout.

3. The increase in milk supplied is associated with the

decline in numbers of children who dropout.

1.6 Significance of the

study

The study will help the government to grasp the overall

performance of one cup of milk per child program in the selected schools as a

way of reducing children dropout level in general. The study will also identify

challenges that face the program and will attempt to suggest adequate

solutions. Besides family poverty, the study will shade light on other

contributing factors to dropout, especially in Rwandan community. The findings

of this study may serve for further researchers in the aim of improving the

program of one cup of milk per child.

1.7 Scope of the study

This study will be carried out in selected primary schools of

Huye district with or without the program of one cup of milk per child.

1.8 Organization of the

study

This study was presented in five chapters:

The first chapter was the general introduction: it gives

background of the study, the statement of the problem, objective of the study,

hypothesis testing, the scope and significance of the study

Second was the literature review, major concepts of the study

and other related work.

The third chapter is the methodology; it presents methods and

techniques employed in data Collection, the sample size and how it is selected.

Chapter four was on data interpretation and analysis.

Chapter five was about summary of the study, findings and

policy implications.

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE

REVIEW

2.1. Introduction

This chapter presents a review of literature on the factors

that define student's dropouts in global level, regional level and Rwandan

local level, especially Huye district. The chapter consists of the theoretical

framework and summary of reviewed literature identification of research gaps

and conceptual framework.

2.1.1 Definition of key

terms

· Students

According to Cambridge dictionary, a student is defined as a

person who is learning at a college or university, or sometimes at a school.

The free online dictionary by FARLEX defines school as

an institution for the instruction of children or people under college age.

· School

Cambridge advanced learner's dictionary defines school as a

place where children go to be educated. It can also be defined as the period of

your life during which you go to school, or the teaching and learning

activities which happen at school.

· One cup of milk per child program

Rwanda Agriculture Board started One Cup of Milk per Child

Program in May 2010 as an implementation of the outcomes of the IDP (Integrated

Development Program) meeting held at MINALOC on 23/04/2010, the resolution that

authorized MINAGRI to start the implementation of «One Cup of Milk per

Child Program». At first, the program started being piloted in 6 Districts

of Bugesera, Kamonyi, Nyanza, Karongi, Gakenke and Ngororero districts. After a

trial period of one year and half that showed that it is possible to run a

school milk program in our country, the scaling up was approved in the meeting

chaired by Right Honourable Prime Minister on 22/07/2011 and started being

implemented in October 2011.

In the up said meeting, MINAGRI was recommended to scale up

the program to other Districts and Schools and to increase the number of

children beneficiaries from 21,300 to 100,000. MINEDUC and MINISANTE were also

requested to assist to identify the needy Districts and Schools. After

different concertration meetings of the three concerned Ministries plus

MINALOC, eight (8) new Districts of Nyamagabe, Nyaruguru, Gisagara, Huye,

Nyamasheke, Rubavu, Rutsiro, Ngoma and Ngororero was retained to enter in the

scaling up of the program. Ngororero District was in the pilot phase with 5

schools and 5 new schools were retained in the scaling up of the program. A

part from the new districts which were scaled up to be in the program, some

other new schools from existing Districts were also added by the year 2013 and

among them six schools were from Nyanza, two from Ruhango and four new schools

from Gisagara. Currently, the program is being implemented in 112 schools from

fifteen Districts and eighty three thousand and five hundred and seventh five

(83,575) pupils are on the program.

The selection criterion of those districts was based on the

2010 report on malnutrition status in our Country especially among children.

The number of schools retained by District was also based on the malnutrition

rate in each District as the priority is given to the neediest as compared to

the allocated budget.

The pupils are given milk of standard quality from Rwandan

recognized dairies namely

INYANGE INDUSTRIES and AGRO PROCESSING INDUSTRIES (API) and

they take half liter twice a week which makes whole liter per week. (MINAGRI

2013)

Table 1 Table showing the

current distribution of milk among children of primary schools of

Huye.

|

N0

|

Province & District

|

School Name

|

Number of pupils as per 3rd term 2013

|

|

SOUTH

|

|

1

|

HUYE

|

Butare Catholique

|

479

|

|

2

|

CJM

|

151

|

|

3

|

Cyendajuru

|

590

|

|

4

|

EP Buremera

|

583

|

|

5

|

EP Busheshi

|

433

|

|

Total

|

2236

|

Source: MINAGRI 2013

Figure 1 Figure showing children

having milk at their disposal in Nyanza district

Source: MINAGRI 2013

Nyanza District: Pupils aligning when they are approaching their

classes after being served milk by their class teachers. (Nyanza serves

fermented milk)

Table 2 Cost and Funding

mechanism of one cup of milk per child countrywide

|

Number of children

|

Milk consumed by each pupil per week

|

Total quantity of milk consumed per week

|

Cost of milk per week

|

Number of weeks per year

|

Cost per year

|

Funds

|

|

83,375

|

One liter

|

83375 liters

|

800 Frw

|

36 weeks

|

2,401,200,000 Frw

|

Government

|

Source: MINAGRI 2013

According to MINAGRI, in charge of distributing milk among

schools, government is the only funder of the program having to spend

2,401,200,000 frw per year. Each child is supposed to consume one litre per

week and the children who are currently covered by this program are estimated

to be 83,375 children. Within Huye district only 5 schools have the program

with 2236 children currently covered with the program.

2.1.2 Dropout

By definition, dropout is a person who has abandoned a course

of study or who has rejected conventional society to pursue an alternative

lifestyle.

School dropout, also, in its simplest meaning is the untimely

withdrawal from school. These students who withdraw from school prematurely end

up not obtaining any certificate of graduation (Ajaja. 2012). However in this

study student dropout refers to the situation in which students fail to

complete a course of study within the usual time.

School dropout can be defined in different manner according to

the field in which the study is based on. In such way CALD3

dictionary defines it as a person who leaves school,

college or university before finishing a course, or a person who leaves in an

unusual way.

2.1.1.2 Drop-out Rate (DR)

The percentage of pupils who leave the school without

completing the grade they were enrolled in during the school year. Dropout rate

can also be obtained by subtracting the sum of promotion rate and repetition

rate from 100 in a given school year. (MINEDUC 2013)

DRt-1

2.2 The literature related

to causes of Dropout

It is clear that the number of children enrolled in school has

increased over time.

Nevertheless, a significant proportion of children who start

primary school are not completing this cycle.

There are many factors associated with this dropout, some of

which belong to the individual, such as poor health or malnutrition and

motivation. Others emerge from children's household situations such as child

labour and poverty.

2.2.1 School level factors

School level factors also play a role in increasing pressures

to drop out such as teacher's absenteeism, school location and poor quality

educational provision. The system of educational provision at the community

level generates conditions that can ultimately impact on the likelihood of

children to drop out from school. Therefore, both demand and supply driven

factors, are embedded in cultural and contextual realities, which make each

circumstance different. Nevertheless, it is possible to make general points

about the causes of drop out.

First, there is not one single cause of drop out. Drop out is

often a process rather than the result of one single event, and therefore has

more than one proximate cause (Hunt, 2008).

Second, distance to schools, poor quality of education,

inadequate facilities, overcrowded classrooms, inappropriate language of

instruction, teacher absenteeism and, in the case of girls school safety, are

common causes for school dropout (Colclough, et al. 2000).

These are seen as supply side causes of drop out, mainly

driven at the school level.

Within gendered social practices, school safety seems to be an

important factor for retaining girls at school, whereas availability of income

generating opportunities and flexible seasonal schooling could promote school

retention for boys (Colclough et al., 2000; Leach et al., 2003). Additional

factors affecting motivations and decision-making relating to educational

access are also keys to understanding of dropping out.

Perceptions of how education will influence lifestyle and

career possibilities/probabilities, life chances in the labor market are shown

to be factors in both early withdrawal and sustained access in different

contexts. The availability of options to access secondary school and beyond,

shape decision-making of parents regarding the continuation of children in

primary level.

Perceived quality of education and the ability of children to

make progress through the schooling system can affect the priority placed on

schooling within the household. It is also evident that children whose parents

have received some sort of schooling are more likely themselves to attend

school for longer. In particular, a mother's education level often influences

length of access for girls. For example in rural Pakistan, girls whose mothers

have some sort of formal schooling are less likely to drop out from school

(Lloyd, Mete and Grant, 2009).

2.2.2 Household (family) level

factors

Poverty also interacts with other points of social

disadvantage, with the interaction of factors putting further pressure on

vulnerable and marginalized children to drop out (Hunt, 2008:52).

In addition, poverty appears to influence the demand for

schooling, not only because it affects the inability of households to pay

school fees and other costs associated with education, but also because it is

associated with a high opportunity cost of schooling for children. As children

grow older, the opportunity cost of education is even larger, hence increasing

the pressure for children to work and earn income for the household as opposed

to spending time in education.

For example, orphans, migrants, lower caste/scheduled tribe

children and children from minority language groups in many, but not all,

contexts have disrupted access, and are more prone to drop out.

For example, around 15 to 20 percent of Roma children in

Bulgaria and 30 percent in Romania do not continue in school post Grade 4 in

primary school (UNESCO, 2010). Poor indigenous girls in Guatemala are far more

likely to drop out than non-poor, non-indigenous girls (UNESCO, 2010). Gendered

social practices within households, communities and schools, influence

differing patterns of access for girls and boys. In most contexts girls have

less access and are more prone to dropping out, but increasingly, often in poor

and urban environments, the pressure seems to be on boys to withdraw.

The study by Holmes (2003) found out that overall; females

receive less education than males, and they tend to dropout, or are withdrawn

earlier for both economic and social-cultural reasons. The study furthers

argues that the opportunity cost of sending female children to school in rural

areas, where girls are married quite early, is high because benefits of their

schooling will not accrue to their parental household. Similarly Kasente,

(2004), Kakuru, (2003) explain how early marriages influence children's

dropping out of school especially as regards the girl child as it is perceived

by parents that marrying off the girl child is an escape route from poverty.

Uganda Participatory Poverty Assessment (UPPAP, 2000) indicates that marrying

off girls would benefit her family in terms of attaining bride price.

Odaga and Heneveld (1995), further note that parents worry

about wasting money on the education of girls because there are most likely to

get pregnant or married before completing their schooling and that once

married, girls become part of another family and the parental investment in

them is lost this therefore perpetuates parents discouraging the girl child

from continuing with school.

Findings with regard to the impact of parent's education on

schooling of children show that the children of more educated parents are more

likely to be enrolled and more likely to progress further through school.

Holmes, (2003) shows that this impact differs by gender, the education of the

father increases the expected level of school retention of boys, and that of

the mother's enhances the educational attainment of girls. Similarly other

studies by Behrman et al. (1999) and Swada and Lokshin (2001) reported a

consistently positive and significant coefficient of father's and mother's

education at all levels of education except at secondary school level.

United Nations Children Education Fund (UNICEF, 1999); MOES,

(1995); Government of Uganda (GOU, 1999) Horn (1992); all demonstrate that

Parental decisions do affect children retention. Students whose parents monitor

and regulate their activities, provide emotional support, encourage independent

decision making and are generally more involved in their schooling are less

likely to drop out of school (Astone and McLanalan, 1991; Rumberge et al.,

1990; Rumber 1995; Odaga and Heneveld, 1995; and Russel, 2001).

Taking into account of the gender dimension of dropouts,

UNICEF, (2005) notes that girls are more likely to drop out of school than boys

and that pupils whose mother's have not attained any level of education will

most likely dropout of school.

Russel, (2001); Bickel and Pagaiannis, (1988); Clark, (1992);

and Rumberger, (1983) demonstrate that communities can influence dropout rates

by providing employment opportunities during school.

While some researchers have found out that work can contribute

to a student dropping out, others have showed that student employment begins to

correlate with dropping out when the student regularly works over 14 hours per

week (Mann 1986, 1989). Other research place the critical level for employment

higher, at 20 hours per week (Winters 1986), with the likelihood of dropping

out increasing with the number of hours worked.

In an account for the gender disparity in primary school

dropout, Nyanzi (2001) put forward that marriage, pregnancy and sickness are

major causes of drop out among girl children while amongst the boys, they

include; jobs, lack of interest dismissal and fees.

2.3 The relating to

consequences of school dropout and strategies to be taken

Personal and societal consequences of dropping out of school

are costly. Dropouts experience Dropouts are also more likely than graduates to

become dependent on welfare, engage in illegal activities, and experience

health and affective problems (Rumberger , 1987). Finally, high rates of

dropping out of school create a negative momentum for youth in a society,

particularly during difficult economic periods when even a high school diploma

does not guarantee a job. Such momentum may foster even higher dropout rate s

in the future.

Most studies that investigated the predictive variable s of

school dropout focused on personal (i.e... behavioral, academic, intellectual)

and familial factors. These studies found that an early disruptive profile

(Ensminge r & Slusarcick, 1992), low achievement in elementary school

(Garnie r et al., 1997), and parental support and supervision

(Howel l & Frese, 1982; Rumberger et al., 1990) predict

early withdrawal from school even after controlling for socioeconomic factors.

However, as underlined by Hymel et al. (1996), far less attention has been

given to the role of peers in contributing to school dropout. More than a

decade ago, Parker & Asher (1987) suggested that social factors may be

better estimates of leaving school without graduating for the majority of

dropouts with average or above intelligence than cognitive or parental factors.

The few studies that investigated the role of peers did so without considering

academic and familial factor s (e.g . Elliott & Voss,1974; Cairns et al.,

1989), however. Consequently, no study (to our knowledge) has considered the

contribution or the role of peer-related variables above and beyond personal

and familial variables in a comprehensive model intended to predict early

withdrawal from school.

Two peer variable s have been linked with dropping out of

school: rejection from conventional peers and association with deviant peers.

For instance, many children with disruptive behaviors experience peer rejection

(Coie , 1990). This is important in that peer rejection has been predictively

linked, in some, but not in all studies, to dropping out of school (se e Hymel

et al., 1996). In addition, many rejected children have no friends in the

classroom tha t might buffe r th e impact of negative social experiences at the

group level. Actually, lack of friend s may increase the risk for school

disengagement. Kupersmidt et al. (1990 ) suggested that rejection from peers

and lack of friend s exacerbated th e frustration s of low grades and

punishment fo r low achievement and increased adolescents ' motivation to leave

school prior to graduation . In support to this position, Kupersmidt (1983)

showed that peer status significantly predicted late r academic adjustment even

after controlling for sex, race, grade point average and child' s reputation

among peers for starting fights. However, in this study, academic maladjustment

included grade retention and truancy and no t jus t dropping out of school.

Ollendick et al. (1992) also reported that 9-year-old rejected children failed

more grades and were more likely to drop out of school 5 years late r than

non-rejected children. Consequently, these negative social experiences may

contribute to or mediate the link between disruptiveness and dropping out.

In addition to their independent or mediating role, peer

acceptance may also condition (i.e. moderate) the propensity of disruptive or

learning disabled children to drop out of school and help explain why some, but

not all at risk children dropout of school.

In turn, peer rejection might be moderated by parental

factors. For example,

Steinberg et al. (1992), showed that parental support for

academic attainment buffered children who were unpopular with their peers from

dropping out of school. However, it is also possible that social acceptance has

no independent contribution to dropping out of school as indicated by finding s

from Kupersmidt & Coie (1990 ) and

School and Community

Perspective

· Systemic Renewal

General Definition: Systemic renewal calls

for a continuing process of evaluating goals and objectives related to school

policies, practices, and organizational structures as they impact a diverse

group of learners.

«To prevent and correct serious attendance problems,

schools need to change the way they are structured, improve the quality of

courses, and intensify interpersonal relationships between students and

teachers» (Epstein & Sheldon, 2002, p. 309).

«Research has identified a student's attitude towards the

school is the single most important factor in combating truancy. It is then the

responsibility of the school administrator to fashion a school where children

want to attend as opposed to having to attend» (Gullatt &

Lemoine,1997,p. 18).

«Systemic solutions to attendance problems will originate

from a system that is made up of teachers and administrators who understand the

connectedness of a supporting climate, significant relationships, engaging and

challenging content and instruction, rules, policies and procedures»

(Wagstaff, Combs, & Jarvis, 2000, p. 29)

· School-Community Collaboration

General Definition: When all groups in a

community provide collective support to the school, a strong infrastructure

sustains a caring environment where youth can thrive and achieve.

«Truancy is costly. . . . It costs businesses, which must

pay to train uneducated workers. It costs taxpayers, who must pay higher taxes

for law enforcement and welfare costs for dropouts who end up on welfare rolls

or underemployed» (Garry, 1996. p. 2).

Successful efforts to improve attendance view truancy as more

than just a «school» issue and involve the entire community (Gullatt,

& Lemoine, 1997).

· Safe Learning Environments

General Definition: A comprehensive violence

prevention plan, including conflict resolution, must deal with potential

violence as well as crisis management. A safe learning environment provides

daily experiences, at all grade levels, which enhance positive social attitudes

and effective interpersonal skills in all students.

One of the causes of truancy is school climate, including

feelings of physical safety (Heilbrunn & Seeley, 2003).

«Victims of bullying suffer consequences beyond

embarrassment. Some victims experience psychological and/or physical distress,

are frequently absent and cannot concentrate on school work» (Sampson,

2004, p. 12).

Bullies are more likely to be truant and drop out of school

(Children who bully, n.d.).

Early Childhood Education

General Definition: Birth-to-five

interventions demonstrate that providing a child additional enrichment can

enhance brain development. The most effective way to reduce the number of

children who will ultimately drop out is to provide the best possible classroom

instruction from the beginning of their school experience through the primary

grades.

«Early absenteeism is an important predictor of dropping

out of high school» (Epstein & Sheldon, 2002, p. 309).

· Early Literacy Development

General Definition: Early interventions to

help low-achieving students improve their reading and writing skills establish

the necessary foundation for effective learning in all subjects.

«The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics and the

National Association for the Education of Young Children affirm that

high-quality, challenging, and accessible mathematics education for 3- to

6-year-old children is a vital foundation for future mathematics learning»

(National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2005).

«Chronic truancy is often the first step on the road to

illiteracy, and all its attendant ills» (American Bar Association, 2001,

p. v).

Basic Core Strategies

· Mentoring/Tutoring

General Definition: Mentoring is a one-to-one

caring, supportive relationship between a mentor and a mentee that is based on

trust. Tutoring, also a one-to-one activity, focuses on academics and is an

effective practice when addressing specific needs such as reading, writing, or

math competencies.

«Students report that having a person at school who is

checking up on them, gives the sense that someone cares and motivates them to

come to school» (Gonzales, Richards, & Seeley, 2002,p.12).

Two major national studies have reported positive results from

mentoring programs. Tierney and Grossman (1995) report a 37% decrease in

truancy among participants in the Big Brother/Big Sister programs. The

Commonwealth Fund's Survey found a 52% decrease in skipping school among

participants of mentoring programs (McLearn, Colasanto, & Schoen, 1998).

· Service-Learning

General Definition: Service-learning connects

meaningful community service experiences with academic learning. This

teaching/learning method promotes personal and social growth, career

development, and civic responsibility and can be a powerful vehicle for

effective school reform at all grade levels.

Service-learning helps students to see the value of education

through direct experiences in the community, and the process develops more

positive attitudes toward school and education in general (Garman, 1995).

«Studies of the effects of service-learning on grades,

attendance, and dropout reduction indicate the value of this strategy for

students who have significant risk factors» (Shumer & Duckenfield),

2004, p. 156.

· Alternative Schooling

General Definition: Alternative schooling

provides potential dropouts a variety of options that can lead to graduation,

with programs paying special attention to the student's individual social needs

and academic requirements for a high school diploma.

«Among the advantages of alternative schools for students

at risk of dropping out are reductions in truancy and drop-out rates, ... and

re-engagement with learning and the community that can occur when students are

in a more responsive and flexible environment» (Paglin & Fager, 1997,

p. 3).

«Graduates of alternative schools report that alternative

school experiences made all the difference in helping them to become productive

citizens» (Morley, 2002, p. 40).

· After-School Opportunities

General Definition: Many schools provide

after-school and summer enhancement programs that eliminate information loss

and inspire interest in a variety of areas. Such experiences are especially

important for students at risk of school failure because they fill the

afternoon «gap time» with constructive and engaging activities.

«After school sports or other programs at the school site

give students a chance to make new friends, experience a positive atmosphere,

and feel a sense of accomplishment, which, in turn, may reduce their likelihood

of skipping school» (DeKalb, 1999, p. 3).

«Well-designed and effectively implemented after-school

programs add to the chances that at-risk students will stay out of trouble,

stay in school, and stay engaged with their education» ( Peterson &

Fox, 2004, p.183).

2.4 Summary of the

literature review

Considering the opinions and ideas from the literature review,

it can be noticed that although countries committed their efforts to strengthen

their education systems, such as increase in enrolment rate, there still are

difficulties that their systems facing, more specifically dropout that cause

certain children to lose benefit from education due to various factors as

mentioned in the literature above. This situation exposes those countries to

taking certain measures or reactions in response to avoid the impact of those

factors, mainly dropout from schools as well as consequences associated with

them. As it was shown above dropping out of school have serious consequences

for students, their families. Students who decided to drop out of school face

social stigma, fewer job opportunities, lower salaries, and higher probability

of involvement with the criminal justice system.

CHAPTER THREE: RESEARCH

METHODOLOGY

3.1. Introduction

Swetnam (2004) defined research methodology as the way to

tackle the question of «how am I going to find out the answers?».The

purpose of this chapter is identifying the appropriate methodology that is

undertaken for this study. This methodology demonstrates the entire process of

this study, as well as an analysis of the various research methods employed

during the conduct of the research. This section describes the practical

procedures for carrying out the study.

It gives the details of the research design that were

adopted, population study, sampling procedures, data collection procedures, and

the final data analysis techniques that will apply. It gives the framework

within which data are collected and analyzed.

Additionally, this chapter examines the research methodology

suitable for analyzing the «Impact of one cup of milk per child on

children dropout». The methodology demonstrates

the entire research process as well as an analysis of the various research

techniques that have been administered. Besides, this chapter considers the

research design and methodology on which the memoire is based.

3.2. General Description of

the study

In this section, the following items are described: population

study, sample size determination and sampling techniques, description of the

instruments of data collection, data processing, data analysis, and limitation

of the study.

3.2.1. Research design

Christensen (1991); defines research design as an outline, a

plan or a strategy specifying the procedures to be used in investigating the

research problem. It is simply the framework or plan a study used as a guide in

collecting and analyzing data. For the purpose of the current study the survey

method will be adopted.

The research Design of this study is exploratory means and

descriptive, that it will involve testing a hypothesis and deriving that

hypothesis from available theories. To gather the needed data, fieldwork will

be conducted in Huye primary schools using double data collection methods.

Questionnaire and interview sheets will be used to

get perception and clear profile of the impact of one cup of milk per child on

dropout of schools. The data was analyzed and presented in comparative

format.

This study will involve both qualitative and quantitative

data. The qualitative data collection technique is subjective in nature since

it involves examining the perception of teachers. Numerical data analysis and

statistical tests are objective in nature and deal with measuring phenomena.

For this study, regression analysis will be conducted; frequencies and

hypotheses testing will be used.

3.2.2. Purpose of the study

The purpose of this study was to analyze the impact of one cup

of milk per child program on children dropout within Huye primary schools.

3.2.3. Study process

The study is fully described and understood. It was important

to analyze in the process through which the study is conducted. This study

holds both quantitative and qualitative study because during the study

numerical data was collected and analyzed. In this research qualitative

hypothesis testing was used because during the study theoretical elements in

depth interviews were considered.

3.2.5. Outcome of the study

The outcome of the study will be used by proceeding

researchers in the related field, decision makers, public sectors and others

with interest of promoting standards of living through the promotion of primary

school learning.

2 .3 Conceptual

framework

A conceptual framework represents the relationship between

variables in the study diagrammatically. The factors that influence the school

dropout within Huye district are illustrated in Figure 2.1 below.

· Dependent variables

The dependent variable is the school level of dropout which is

affected positively or negatively by different variables including school

level, household level, and community level factors.

· Independent variables

The independent variables that can affect positively or

negatively the levels of dropout are: the illiteracy of child's parents,

child's family poverty, long distance from school, failure or repetition,

etc.

Figure 2 Conceptual Framework

between Level of dropout and factors affecting it

The Illiteracy of child's parents

Corporal punishment of children at schools

Primary School dropout level.

Child's family poverty

Child employment

Distance of child's household from the school

![]()

Repetition of failure of children

Source: Author

3.4 Geographical

location of huye district

HUYE district is located in southern province of

Rwanda.

Figure 3 Geographical

location of Huye district

Source: Arc GIS

The district of Huye is located in the southern province of

the Republic of Rwanda, whereby it is known as one of advanced regions in

education industry of Rwanda. This district is the one which recognized the

existence of the first University to be in Rwanda since 1963. Besides this Huye

district has known famous schools in secondary studies as well as in primary

learning. Basing on the intention the researcher in conducting this research,

Huye district currently is employing 1100 teachers within primary schools who

are counted within only 98 primary schools which are under the supervision of

the director in charge of education within the district.

Certain schools are located in urban areas whereas others are

found in rural areas of Huye district.

3.5 Population study,

Sample size and Sampling techniques

3.5.1 Target

population.

Grinnell et al (1990) defined population as the totality of

persons or objects concerned with the study. Manheim & Rich (1995) define

population as a set cases about which one wishes to draw some conclusions. In

this research the populations are all primary schools of Huye.

The sample survey will be applied on selected schools with and

without the program of one cup of milk per child in HUYE district. The

population sample which will be used in the research was 60 teachers as well as

headmasters from selected schools in Huye district. The researcher will collect

data from the sample by using questionnaires and interviews.

3.5.2 Sampling design

Sampling is concerned with the selection of a subset of

individuals from within a statistical population to estimate characteristics of

the whole population.

MARK .L. and David (1990) state that it is usually too time

consuming, costly cumbersome and insufficient to motivate, do or obtain a

complete census or count of the target population. Thus, the researcher decides

it is his goal to make inferences about the entire population inclusive in the

research study. However though a necessary evil, this is contrary to some

scholars as they ideally feel that the whole population should be used to get

the information for the researcher.

A sample design is a definite plan for obtaining a sample from

a given population. It refers to the technique or the procedure the researcher

adopted in selecting items for the sample.

Berman (2006) provided the advantages of sampling population

are:

· The likelihood that it will cost less to sample than to

do a census, why ask all people within primary schools Huye, when you can

reliably get what you need to know by asking a few among them?

· The possibility of greater accuracy

· The greater speed of data collection

· The time management

3.5.3 Sample size determination

3.5.4 Sample selection

From the population of 98 primary schools of Huye, 4 schools

were selected.

To ensure that all people were equally represented, the

researcher used proportional stratified sampling as shown in table below as a

result 60 teachers in selected primary schools were selected at 95% of

confidence level.

Table 3.1:

Table 3 Sample

selection

|

Schools

|

With the program

|

Without the program

|

Total

|

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

|

Teachers

|

18

|

16

|

10

|

16

|

60

|

|

Headmaster/ head teacher

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

4

|

Source: Author

3.6. Description of the

instruments of data collection

The researcher will use the questionnaire, interview schedule

and documentation.

3.6.1. Questionnaire

As defined by Grinnell and Williams (1990) questionnaire is a

set of questions which calls for responses on the part of the client, may be

self administered or group administered. This method is used to collect data

from respondents hoping to get people's perceptions, feelings and views since

each respondent will be given time to fill the structured questionnaire and

justifications for the responses given whenever it was necessary.

3.6.2. Interview schedule

Unlike the questionnaire, the researcher himself will use a set

of structured questions where questions will be read to the respondents and

answers given will be recorded. Due to the importance of the information from

some respondents in the institutions of the study and due to the limited time

these people may have to fill the questionnaire, the interview schedule may be

found appropriate to save time and have this important information at the

research disposal.

3.6.3. Documentation

Documentation is another technique that will be used along

with interviews and questionnaires. This involves primary analysis of related

documents. By this instrument, literature was reviewed especially the writings

of other authors on the subject matter of the study.

3.7. Data Processing and

Analysis

Data processing is broadly, the collection and manipulation of

items of data to produce meaningful information. In this sense it can be

considered a subset of processing, the change of information in any manner

detectable by an observer. It is important to show the various tools at which

the data were obtained from the field.

Data analysis is the process of systematically applying

statistical and or logical techniques to describe and illustrate, condense and

recap, and evaluate data. According to Shamoo and Resnik (2003) various

analytic procedures provide a way of drawing inductive inferences from data and

distinguishing the signal(the phenomenon of interest) from the noise

(statistical fluctuations) present in the data.

3.7.1. Coding

Coding will be used to summarize data by classifying different

responses in categories that are easily understandable.

3.7.2. Editing

Editing refers to a process whereby errors are eliminated

whenever identified in interview schedules and the questionnaires. The

researcher followed this procedure in order to minimize errors and mistakes.

Unnecessary phrases, words and repetitions, and other sorts of such kind will

be minimized to facilitate accuracy, uniformity legibility and consistency of

data to the best of the researcher.

3.7.3. Tabulation

The tabulation process will involve determination of the

frequency of the responses for every variable and fixing data into statistical

tables. Kakinda (1990) says that after data is edited and coding frame

established, and data coded, it is often tabulated and may undergo other

statistical manipulation.

3.8 Methods of data

analysis

The researcher used two types of methodologies, namely:

descriptive statistics (frequency statistics and bivariate analysis) and

multivariate analysis using multinomial logistic regression which was used to

identify the direction of effect for each independent variable adjusting for

the others on the level of dropout existing in schools within whhich this

research was conducted.

3.8.1 Descriptive

statistics

The descriptive statistics of variables is important for

summarizing the characteristics of the sample. Bivariate analysis using

chi-square test was used to identify if there is a relationship between the

dependent variable and each independent variable.

The chi-square formula is

Where O is the observed frequency in each category of

independent variable

E is the expected frequency in the corresponding category of

independent variable

: is the chi-square value

: is the chi-square value

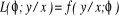

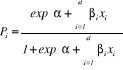

3.8.2 Multivariable

analysis

Multivariable logistic regression analysis extends the

techniques of multiple regression analysis to research situations in which the

outcome variable is categorical (Dayton 1992). Generally, logistic regression

is well suited for describing and testing hypotheses about relationships

between a categorical outcome variable and more categorical predictor

variables. Multinomial logistic regression was typically used in this study

because the dependent variable has more than two categories (Bender and Grouven

1997)

3.8.3 Multivariable logistic regression

model

The conditional likelihood by a set of parameters ( ) given data (x and

) given data (x and  ) is

) is  . Intuitively,

. Intuitively,  follows a probability distribution that is different for x, but x

itself is never unknown, so there is no need to have a probabilistic model of

it. For each x there is different distribution of

follows a probability distribution that is different for x, but x

itself is never unknown, so there is no need to have a probabilistic model of

it. For each x there is different distribution of , but all these distributions share the same parameters (

, but all these distributions share the same parameters ( ). Given data consisting of (

). Given data consisting of ( ) pairs, the principle of maximum conditional likelihood says to choose

a parameter estimate

) pairs, the principle of maximum conditional likelihood says to choose

a parameter estimate  that maximizes the product

that maximizes the product . Note that we do not need to assume that

. Note that we do not need to assume that  are independent in order to justify the conditional likelihood being a

product; we just need to assume that

are independent in order to justify the conditional likelihood being a

product; we just need to assume that  are dependent when each is conditioned on its own

are dependent when each is conditioned on its own . For any specific value of x,

. For any specific value of x,  can then be used to predict values for y; we assume that we never want

to predict values of x. Suppose that y is a multinomial outcome and that x is a

real-valued vector. We can assume that the distribution of y is a fixed

nonlinear function of a linear function of x. Specifically. We assume the

conditional model:

can then be used to predict values for y; we assume that we never want

to predict values of x. Suppose that y is a multinomial outcome and that x is a

real-valued vector. We can assume that the distribution of y is a fixed

nonlinear function of a linear function of x. Specifically. We assume the

conditional model:

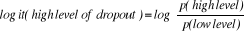

Responses ( 's) are categorical variables with more than two categories (coded 1 for

high level, code 2 for middle level, coded 3 for low level of dropout).

Predictor values (

's) are categorical variables with more than two categories (coded 1 for

high level, code 2 for middle level, coded 3 for low level of dropout).

Predictor values ( 's) can be categorical. We are interested in modeling

's) can be categorical. We are interested in modeling  in terms of

in terms of :

:

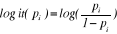

is a multinomial random variable, whose proportion parameter

is a multinomial random variable, whose proportion parameter depends on predictors' variable

depends on predictors' variable . The ratio

. The ratio  is called the odds of the event y given and

is called the odds of the event y given and  is called the log of odds. Since probabilities ranged between 0 and 1,

odds range between 0 and 1, odds range between 0 and

is called the log of odds. Since probabilities ranged between 0 and 1,

odds range between 0 and 1, odds range between 0 and  , log odds range unboundedly between

, log odds range unboundedly between  . A linear expression of the form

. A linear expression of the form  can also take unbounded values, so it is reasonable to use a linear

expression as a model for log odds, but not as a model for odds for odds or for

probabilities. Essentially, logistic regression is the simplest reasonable

model for a categorical outcome that depends linearly on predictors

can also take unbounded values, so it is reasonable to use a linear

expression as a model for log odds, but not as a model for odds for odds or for

probabilities. Essentially, logistic regression is the simplest reasonable

model for a categorical outcome that depends linearly on predictors . For each feature i,

. For each feature i,  is a multiplicative scaling factor on the odds

is a multiplicative scaling factor on the odds . If the predictor

. If the predictor  is real-valued, then

is real-valued, then  is the extra odds of having the outcome y=1 when the value of

is the extra odds of having the outcome y=1 when the value of  increased by one unit.

increased by one unit.

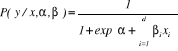

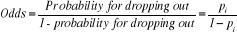

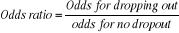

In fact, the ratio is the probability of occurrence of an

event to the probability of its not occurrence. If there is a probability  for the level of dropout, then the odds can be considered the ratio of

the probability for the level of dropout over the probability for no

dropout.

for the level of dropout, then the odds can be considered the ratio of

the probability for the level of dropout over the probability for no

dropout.

An odds ratio (OR) is a measure of association between an

exposure and an outcome. The OR represents the odds that an outcome will occur

given a particular exposure, compared to the odds of the outcome occurring in

the absence of that exposure.

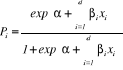

Multinomial logistic regression models make it possible to

estimate the probability for dropout level on the combination of independent

variables included in the model.

The model in terms of probability of outcome occurring is:

= Odds ratio for a person having characteristics i versus not having

it

= Odds ratio for a person having characteristics i versus not having

it

=Regression coefficients

=Regression coefficients  =constant

=constant  = ith variable Where; i=1, 2, ...., k

= ith variable Where; i=1, 2, ...., k

= probability of outcome occurring

= probability of outcome occurring

3.9. Limitation of the

Study

In this study the researcher faced a number of problems:

· Time and financial resources.

· The refuse of some respondents during the data

collection process

· Limited access to secondary data concerning the records

relating to the program since the starting time of its implementation

CHAPTER FOUR: DATA ANALYSIS

AND INTERPRETATION

4.1 Introduction

As reviewed in chapter two, the level of dropout within

primary schools was influenced by various independent varibles either

positively or negatively. Therefore, this chapter showed whether those factors

including one cup of milk per child program, long distance from school, prent's

illiteracy, family poverty, etc. Influence the level of dropout within primary

schools of Huye.

Whithin this chapter the researcher dealt with the analysis

and interpretation of the data collected for the achievement of the objectives

as described in chapter one. It involved the presentation of data, discussion

of major findings of the study and their interpretation. Percentage,

frequencies were used as means of analyzing and interpreting the data, some

hypotheses were tested using statistical tests such as chi-square.To make data

analysis more understandable and clear, data collected was analyzed, tested and

interpreted before drawing conclusion. The analysis was made on sample of 60

primary school teachers as well as headmasters of the selected schools taken

from the whole population of the schools in Huye district. The statistical

analysis package used during the analysis was SPSS version 16.

4.2. Profile of

respondents:

The following results have been found by discussing with about

60 primary teachers from 4 selected primary schools of Huye. the aim was to

make the findings of the study more easily analyzed, presented and interpreted

. The aim was evaluating whether the milk provision into primary schools can

contribute to the reduction of school dropout and testing the impact that other

factors have on the dropout level.

Below is the Figure 4 showing the distribution of respondents

by both their level of education and gender whereby 33.3 percent were male

categorized into 30 percent having secondary level of education and technical

studies and 3.3 percent of those with university level and other higher

learning institutions. Females were counted to 66.7 percent divided into 55 of

those with secondary education leve and 11.7 percent of those with university

and other higher learning institutions.

Figure 4 Distribution of

respondents by their education level and Gender

Source: primary data

4.2 Results from the

percentage distribution of respondents by the level of dropout

Before describing the bivariate analysis and multinomial

logistic analysis, the study shows how the level to which students were

dropping out of schools by describing the percentages of each category as

mentioned in the table 4.1.

Table 4 Percentage

distribution of respondents by the level of dropout

|

Level of dropout

|

Percent

|

|

High

|

33.3

|

|

middle

|

23.3

|

|

low

|

43.3

|

|

Total

|

100.0

|

Source: primary

The table 4.1 illustrates that among all respondents to whom

the research was conducted, 33.3 percent of them reported that the level of

dropout within their schools was high while 23.3 percent reported that the

dropout within their schools was at the middle level. Finally, 43.3 percent

which represents the highest ratio reported that the dropout in their schools

was low.

Table 5 Percentage

distribution of respondents by factors affecting dropout

|

Variables

|

Percent

|

|

Distance from school

|

Yes

|

56.7

|

|

No

|

43.3

|

|

Total

|

100.0

|

|

Parents' illiteracy

|

Yes

|

76.7

|

|

No

|

23.3

|

|

Total

|

100.0

|

|

Child's Family poverty

|

Yes

|

81.7

|

|

No

|

18.3

|

|

Total

|

100.0

|

|

One cup of milk per child

|

Yes

|

55.0

|

|

No

|

45.0

|

|

Total

|

100.0

|

|

Failure or repetition

|

Yes

|

78.3

|

|

No

|

21.7

|

|

Total

|

98.3

|

|

Child employment

|

Yes

|

80.0

|

|

No

|

20.0

|

|

Total

|

100.0

|

Source: primary data

Table 4.2 shows that out of all respondents questioned whether

there is an influence of the distance from schools to the dropout decision of

children, 56.7 percent of respondents confirmed that it has an influence

whereas 43.3 percent neglected its influence on dropout. Concerning the

parents' illiteracy impact on dropout, 76.7 percent confirmed its impact

against 23.3 percent who denied its effect. Family poverty of children was

agreed to influence the dropout by 81.7 percent of respondents against 18.3 who

denied its effect. Out of respondents who were asked whether the program of one

cup of milk per child can help reducing the dropout level within schools 88.3

percent affirmed its effect against 11.7 percent who neglected it. Failure or

repetition of children was mentioned to be among the causes of dropout at 78.3

percent whereas 21.7 percent denied its effect. Finally, child employment was

considered among causes of dropout by 80 percent of respondents while 20

percent did not consider it.

4.3 Descriptive statistics

of causes of dropouts by the level of dropout

Table 6 Percentage

distribution of factors affecting dropout by the level of dropout

|

VARIABLES

|

LEVEL OF DROPOUT

|

TOTAL

|

|

HIGH

|

MIDDLE

|

LOW

|

|

Distance from school

|

Yes

|

26.5

|

32.4

|

41.2

|

100.0

|

|

No

|

42.3

|

11.5

|

46.2

|

100.0

|

|

Total

|

33.3

|

23.3

|

43.3

|

100.0

|

|

Parents' illiteracy

|

Yes

|

32.6

|

30.4

|

37.0

|

100.0

|

|

No

|

35.7

|

0.0

|

64.3

|

100.0

|

|

Total

|

33.3

|

23.3

|

43.3

|

100.0

|

|

Child's Family poverty

|

Yes

|

36.7

|

20.4

|

42.9

|

100.0

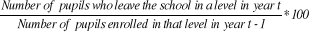

|

|

No

|

18.2

|

36.4

|

45.5

|

100. 0

|

|

Total

|

33.3

|

23.3

|

43.3

|

100.0

|

|

One cup of milk per child

|

Yes

|

12.1

|

18.2

|

69.7

|

100.0

|

|

No

|

59.3

|

29.6

|

11.1

|

100.0

|

|

Total

|

33.3

|

23.3

|

43.3

|

100.0

|

|

Failure or repetition

|

Yes

|

34.0

|

23.4

|

42.6

|

100.0

|

|

No

|

30.8

|

23.1

|

46.2

|

100.0

|

|

Total

|

33.3

|

23.3

|

43.3

|

100.0

|

|

Child employment

|

Yes

|

37.5

|

20.8

|

41.7

|

100.0

|

|

No

|

16.7

|

33.3

|

50.0

|

100.0

|

|

Total

|

33.3

|

23.3

|

43.3

|

100.0

|

|

Place of residence

|

Urban

|

27.6

|

20.7

|

51.7

|

100.0

|

|

Rural

|

38.7

|

25.8

|

35.5

|

100

|

|

Total

|

33.3

|

23.3

|

43.3

|

100.0

|

Source: primary data

The table 6 shows the percentage distribution of between

variables affecting the dropout and the level of dropout.

4.3.1 Distance from school

The table 6 illustrates that among the respondents who

affirmed the distance from school to be one of dropout causes, 26.5 percent

were from schools with high level of dropout while 32.4 percent were from

schools with middle level of dropout and 41.2 percent were from schools with

the low level of dropout. On the other side, respondents who denied the

influence of distance from school to the dropout level, 42.3 percent among them

were from schools with high level of dropout, while 11.5 percent were from

schools with middle level of dropout, and the other 46.2 were from schools with

the low level of dropout.

4.3.2 Parents' illiteracy

The table 6 shows that out of respondents who confirmed the

impact of parents' illiteracy on children's dropout decision, 37.0 percent

representing the highest percentage were from low level dropout schools against