AN EXPLORATION OF TOOLS OF ANALYSIS COMMONLY USED

BY PRIVATE EQUITY IN MAKING INVESTMENT DECISION

By

STEVE ARMAND BOYOM KOUOGANG

LSC STUDENT NUMBER:

L0938FKFK0210

UWIC STUDENT

NUMBER: 10008097

Presented as part of the requirement for the award of MBA at

University of Wales Institute Cardiff (UWIC)

September 2011

The concept of investing behaviour regarded as a probable

cause of the decline in the number of investment activities of venture capital

over the last three years constitutes the background of this dissertation. Its

aims are to investigate the classic tools of analysis, which could be found in

the financial literature, when it comes to make investment decision. Another

objective is to determine the applicable technique of evaluating flexible and

reversible start-ups' investment proposals. The third aim consists of

conducting a survey of venture capital analysts to find out their practice by

way of capital budgeting for start-ups. The fourth is to suggest beneficial

solutions to both parties involved in making such an investment decision, that

is to say private equity analyst and start-up company. The research questions

are: what are the classic methods capable of helping venture capitalist to make

investment decision devoid of any flexibility with regard to start-up

companies? In case the newly created firm's project gets some flexible and

reversible aspects, how should the venture capitalist make investment decision?

What can we learn from an inquiry into the practice of venture capitalist in

the field of determining the investment decision for newly created companies?

Are the findings from the investigation into the way the venture capitalists

make investment decision in practice profitable to both the main players,

namely venture capital firms and new entrepreneurs? Both discounted and

non-discounted cash flow methods are usable classic methods for appraising

newly created firms' capital expenditure. Moreover, in making flexible

investment decision for start-ups, real options turn out to be suitable.

Furthermore, it emerged from data collected with the help of an electronic

questionnaire and analysed in accordance with the qualitative philosophy of

research that 50 percent of private equity firms were more attracted by

investing in Health care. Concerning the techniques used by venture capital

analysts in making start up organisations' non-flexible capital budgeting

decision devoid of any flexibility, we noticed that a third of those analysts

said referring to NPV. Conversely, the revelation appeared to be that private

equity analysts did make a sweep clean of the IRR technique in this respect.

Thirdly, by way of making flexible capital budgeting decision for start up

organisations, the NPV method was in the lead with 37.5% of use when real

options only scored 12.5%.

We would like to extend our warmest thanks to all those people

and firms whose reviews and suggestions contribute to the achievement of this

dissertation.

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION...................................................................................

5

CHAPTER II LITERATURE REVIEW

....................................................................8

CHAPTER III RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

......................................................21

CHAPTER IV FINDINGS AND DATA ANALYSIS

...............................................31

CHAPTER V CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

...............................51

BIBILOGRAPHY..................................................................................................59

APPENDIX

.............................................................................................................

.....63

1.1 RESEARCH CONTEXT

There are a number of venture capitalists whose aims are to

provide capital to ventures, which failed to obtain funds from the conventional

sources such as banks as suggested by Wright and Robbie (1998).This does not

mean that nothing could be easier than being funded by venture capitalists for

start-up companies. In fact, in accordance with the British Venture Capital

Association (BVCA), «Private Equity and Venture Capital

firms invested £7.5 billion globally in 2009, compared to £19.5bn

invested in 2008 and £31.6bn in 2007. In 2009, 987 companies received

private equity or venture capital backing, in contrast to 1,672 in 2008 and

1,680 in 2007» (Private Equity and Venture Capital Report on

Investment Activity, 2009).

Clearly, the above figures suggest investment activities of

venture capitals have declined significantly reaching a half comparing with

what they were 3 years ago. To what could this drop attribute? Broadly

speaking, some (such as «2009 Fidelity Investments Couples Retirement

Study, Executive Summary» cited by Roszkowski and Davey, 2010, p.

42-43) have put all the blame on the 2008 global economy collapse. Whereas,

other have pointed out the notion of risk, especially the concepts of

«risk tolerance» and «risk perception» arguing that both

of those risks determine investing behaviour (Roszkowski and Davey, 2010, p.

43). The topic of this research rests on this background. Having said that,

what are the objectives of this dissertation?

1.2 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

The purpose of this investigation is to examine the various

tools, which could be considered in a particular way when it comes to make

investment decisions for new ventures. Because we are, to some extent, in

favour of the second argument mentioned in the end of the previous section, we

will further explore the different methods, whether based on the theory and /

or practical point of view, and used by venture capitals to grant funds to

start-up companies. Indeed, our objectives are:

1. To carry out a meticulous breakdown of the traditional

tools, which could be used to determine what real assets of a newly created

firm the venture capitalist should invest in.

2. To find out which method can be applicable when the

start-up organisation's project in question is to some extent flexible and

reversible.

3. To survey some venture capital firms in order to catch on

what techniques they use in practice to analyse investment project of start-up

industries.

4. And to recommend solutions based on my research, which will

help venture capitalists as well as fresh entrepreneurs to identify what

criteria could be much more suitable to distinguish fruitful ventures from

unsuccessful projects.

The aforesaid purposes required some research questions that

will be explored.

1.3 RESEARCH QUESTIONS

In order to attain the above set objectives, the following

questions are raised:

1. What are the classic methods capable of helping venture

capitalist to make investment decision devoid of any flexibility with regard to

start-up companies?

2. In case the newly created firm's project gets some flexible

and reversible aspects, how should the venture capitalist make investment

decision?

3. What can we learn from an inquiry into the practice of

venture capitalist in the field of determining the investment decision for

newly created companies?

4. Are the findings from the investigation into the way the

venture capitalists make investment decision in practice profitable to both the

main players, namely venture capital firms and new entrepreneurs?

In any case, we should now turn to know more about the answers

from the scientific writings on this topic in chapter 2.

Moreover, chapter 3 constitutes the research methodology while

chapters 4 and 5 are respectively devoted to

data analysis and findings, and conclusion and recommendations.

|

CHAPTER II LITERATURE REVIEW

|

The purpose of this chapter consists in shedding more light

on the relevant scientific writings referring to the methods ordinarily used by

private equity finance when it comes to make investment decision for start-up

companies. Boosted by what precedes, it would be methodical to define any key

concept of this topic. For that aim, a deductive reasoning will be employed;

therefore this work will by turns scrutinize the concepts of «private

equity» first, «investment decision» secondly and

a wide range of «tools» that allow private equity to determine what

real assets need to be invested in finally. This literature review will then

ended with the bare bones of the main points raised.

2.1 THE CONCEPT OF PRIVATE EQUITY

The roots of «private equity», with regard to the

attention the academic community paid to that term at least, can be stretched

far back into the 80s as argued by Wright and Robbie (1998). In any case, the

notion of «private equity» has recently been devised in a broad sense

as «[involving] investment in unquoted companies, [and it includes] both

early stage venture capital, and later stage buyouts» (Wood and Wright,

2009, p. 361).

This conception of the term «Private equity» echoes

that of Brealey, Myers and Allen (2008). Indeed, according to these authors the

notion of private equity could be defined as «equity that is not publicly

traded and that is used to finance business start-ups, leveraged buyouts,

etc.» (Brealey, Myers and Allen, 2008, p. G-10).

Clearly, from the above definitions there is a convergence on

the broad understanding of «private equity» because of its features,

namely money invested in venture and not listed companies. Moreover, this

conception has been adopted in practice. In fact, the British Venture Capital

Association (2010) states «the term private equity is

generally used in Europe to cover the industry as a whole, including both

buyouts and venture capital» (BVCA, 2010, p. 14).

However, the BVCA itself carries on drawing the difference between private

equity and Venture capital. The former «describes equity investments in

unquoted companies, often accompanied by the provision of loans and other

capital bearing an equity-type risk». The latter, however, constitutes a

«subcategory covering the start-up to expansion stages of investment»

(BVCA, 2010, p. 14).

With regard to the concept of start-up, Arnold (2004)

suggested a definition in 2004. In his opinion, a start-up company or

«startup» is a

company with a limited or

non-existing operating history (Arnold, 2004, p. 388). These companies,

generally newly created, are in a phase of

development and

research for

markets. The term became

popular internationally during the

dot-com bubble

covering roughly 1995-2000 when numerous

dot-com

organisations were created (

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dot-com_bubble).

At any rate, throughout this paper private equity will be

perceived in a broad sense. This is due to the fact that the focus here are the

techniques used to carry out investment appraisal for start up companies. The

term «private equity», under this consideration, will therefore

allude to «venture capital». We should now turn to scrutinise how the

scientific writings consider the concept of «investment decision»

2.2 THE NOTION OF INVESTMENT DECISION

To start with, it should be appropriate to comprehend the

concept of investment decision by examining the scientific writings on

«investment» and «investment decision» successively.

2.2.1 Investment

Generally speaking, «investment» means the use of

money in the hope of

making more money. (www.encarta.msn.com/encnet/dictionary/dictionaryhome.aspx).

More specifically in finance, the concept of

INVESTMENT refers to the

purchase of a

financial

product or other

item of

value with an

expectation of favourable future returns. (

http://www.investorwords.com/2599/investment.html#ixzz1KcRjbPHc).

Two authors, Arnold (2008) and Chandra (2008), further develop

this conception of the term «investment». According to the former

(2008), «investment involves resources being laid aside to produce a

return in the future, for instance, today's consumption is reduced in order to

put resources into building a factory and the creation of machine tools to

produce goods in later years.» (Arnold, 2008, p. 20). In addition, the

latter (2008) conceives investment as «a sacrifice of current money or

other resources for future benefits.» (Chandra, 2008, p. 3). What about

investment decision especially?

2.2.2 Investment decision

As far as corporate finance is concerned, there are two

essential issues that need to be addressed. «First, what real assets

should the firm invest in? Second, how should the cash for the investment be

raised? The answer to the first question is the firm's investment,

or capital budgeting, decision. The answer to the

second is the firm's financing decision» (Brealey, Myers

and Allen, 2008, p. 4). Capital budgeting is also named by scholars

«Capital expenditure -capex-», that is the «selection of

investment projects» (Arnold, 2008, p. 50).

From all what precedes, there is no doubt that the second

decision is by far out of the remit of this research topic. As a result,

venture capitalist should have to find only answers to the first question.

Doing so, the sheer scale of the problem has something to do with the methods

he or she will use for the purpose of investment appraisal. We should now turn

to examine this issue in the light of the relevant academic research.

2.3 FINANCIAL THEORIES ON TECHNIQUES USED BY PRIVATE

EQUITY FOR INVESTMENT APPRAISAL

There has been a wide range of academic writings on private

equity's investment appraisal as a whole. In fact, those writings were

focussing in particular on standards that venture capital firms refer to in

making investment decision. This has been shown by the following authors:

MacMillan, Siegel and Subbanarasimha (1985), MacMillan, Zemann and

Subbanarasimha (1987), and Zacharakis and Meyer (2000). Primarily, the

aforementioned benchmarks are consisted of four components: firstly product

characteristics, secondly market characteristics, thirdly company's financial

position and outlook, and finally the characteristics of the entrepreneur or

management team.

Five years later,

Wright

and Proimos (2005) carried out a pilot study of venture capital investment

appraisal in Australia. They explored both the «investment process and

some of the strategies used by [Venture Capitalists] for reducing selected

risks. The specific source of risk examined [was] information asymmetry, which

is caused by lack of information on the part of the [Venture Capitalists], and

which can lead to the added risks of adverse selection and moral hazard» (

Wright

and Proimos, 2005). Broadly speaking, this work concentrated mainly on the

investment process. In fact, by surveying four Australian venture capital firms

these authors found that those organisations did utilise Berger and Udell's

(1998) three stages of investment model, that is to say selection, contracting

and monitoring.

It has to be pointed out to both

Wright

and Proimos (2005) credits that their paper seems to be a clear and recent

contribution to the understanding of the series of actions taken into

consideration by private equity for making investment decision, albeit it does

not dwell that much upon the methods as such used whilst appraising proposals.

We should therefore move on to the investigation of any tools of investment

evaluation.

With respect to that purpose, financial theories provide

numerous techniques for investment evaluation, for example Net present Value,

Internal rate of return, Payback period, Profitability index, Accounting rate

of return and Real options. The latter, which has come to light in the 80s,

started attracting scholars attention in the 90s as suggested by Borison

(2005, p. 17); thus it is deemed as a recent means of investment appraisal

whereas the five other out of the list could be called classics methods.

2.3.1 Traditional tools of investment assessment

Prior research into traditional tools of investment appraisal

makes out discounted cash flow that can be distinguished from non-discounted

cash flow methods. (

www.swlearning.com/finance/brigham/ifm8e/web_chapters/webchapter28.pdf

, p.28-1;

www.//portal.lsclondon.co.uk/resources/file.php/879/Lec_23/Investment_Appraisal.pdf

, p. 15). This philosophy will be taken up here and further followed under this

section. Be that as it may, the rule of time value of money constitutes the

basis of that distinction as shown for instance by Arnold (2008, p. 50),

Chandra (2008, p. 116) and Vernimmen et al. (2009, p. 289). In fact, these last

authors make use of a metaphorical quote to represent the time value of money

in these terms: «a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush».

Roughly speaking, this prime financial principle suggests for example that a

pound today is more valuable than a pound a year hence. As support for such a

claim, Chandra (2008, p. 116) highlighted two major reasons. Firstly, if

someone makes up his mind to invest his pound now, it can be a source of

positive returns. Secondly, a pound today stands for a more meaningful

purchasing power than a pound a year later than now in case of inflation

especially.

2.3.1.a. Discounted cash flow techniques

As previously mentioned, Net present value (NPV) and Internal

rate of return (IRR) are on focus here.

Concerning the former, previous academic writings have viewed

it as a «project's net contribution to wealth» (Brealey, Myers and

Allen, 2008, p.G-9). According to

Vernimmen

et al., (2009), there is a triple interpretation of the notion of Net present

value. To start with, Net present value refers to «the value created by an

investment - for example, if the investment requires an outlay of €100 and

the present value of its future cash flow is €110, then the investor has

become €10 wealthier.» Moreover, Net present value means «the

maximum additional amount that the investor is willing to pay to make the

investment - if the investor pays up to €10 more, he/she has not

necessarily made a bad deal, as he /she is paying up to €110 for an asset

that is worth 110.» At last, Net present value is also «the

difference between the present values of the investment (€110) and its

market values (€100).» (2009, p. 296).

Relating to Net present values calculations, since the 80s,

there has been a widespread agreement among scholars with regard to the

estimation of cash flows as suggested by the writings of the following authors:

McMahon (1981), Mukherjee (1988), and Patterson (1989).

Even more recently, Brealey, Myers and Allen, (2008, pp.

160-161), Vernimmen P. et al., (2009, p. 296), consider cash flow calculations

in a particular way. Kalyebara and Ahmed (2011, pp. 63-64), further enumerate

10 general principles for doing so. However, these rules could be simplified to

a set of 3 related benchmarks. In the first place, in order to avoid bad

judgment a financial manager should make sure he or she does «discount

cash flows, not profit». In the second place, he or she should ensure the

project's incremental cash flows are assessed, that is «the difference

between the cash flows with the project and those without the project». In

the third place, he or she needs to «treat inflation consistently.»

(Brealey, Myers and Allen, 2008, pp. 160-161). The Chief Finance Officer of a

private equity firm for example should now turn to rank the project properly

speaking.

In order to so, he or she will look at the project Net

Present Value. If this is greater than zero, the proposal will be accepted.

Nonetheless, the project will be rejected on the contrary circumstances. As

generally admitted by the academics, the Net present value rule «measures

the creation or the destruction of value that could result from [...] making

investment [decision]» (Vernimmen et al., 2009, p. 302). Because

maximising the value of shareholders wealth is the core objective of the firms,

a positive net present value means in a simply way that the return of the

selected project goes beyond the investor's expectations. Therefore, there is

to this extent a consensus among academics. In fact, many authors such as

Arnold (2008, p. 56), Vernimmen et al. (2009, p. 296), Droms and Wright (2010,

pp. 193-194) and Kalyebara and Ahmed (2011, p.54) do agree with the idea that

Net present value method constitutes the route that goes to good investment

decision. However, the Net present value seems not to be a «panacea».

As a matter of fact, the Net present value shortcomings have

been pointed out. To begin with, Vernimmen et al., (2009) find that technique

difficult to figure out instinctively and directly. Moreover, Net Present value

does not have a high opinion of «the value of managerial flexibility, in

other words the options that the manager can exploit after an investment has

been made in order to increase its value» (Vernimmen et al., 2009, p.

297). Finally, thanks to its easiness of use, the figure arising from the

Internal Rate of Return attracts more financial managers than that of the Net

Present value tool does. An evidence of the widespread use of The Internal rate

of return can be found in a survey of 4,440 United States organisations

conducted by Graham and Harvey (2001) 10 years ago. Their results showed that

«74.9% [chief finance officers] always or almost always use the internal

rate of return», which was roughly 1% more than those who referred to the

Net present value criterion. (Graham and Harvey, 2001, p. 193).

Relating to the latter discounted cash flow tool, it should

be noted that this method is regarded by the entire academic community

(Brealey, Myers and Allen, 2008, p. 117; Vernimmen et al., 2009, p. 297) as an

earnest challenger of the net present value method. Notwithstanding, what does

the Internal rate of return technique mean?

Droms and Wright (2010, p. 194) suggest that it is the

«discount rate that exactly equates the present value of the expected

benefits from a project to the cost of the project». This conception

echoes with that of Brealey, Myers and Allen (2008). They devise the Internal

rate of return as the «discount rate at which investment has zero net

present value» (Brealey, Myers and Allen, 2008, pp. G-7).

Regarding its calculation, there is also a consensus on the

view that it is found with the help of «trial and error» in a

customary way (Droms and Wright, 2010, p. 194; Brealey, Myers and Allen, 2008,

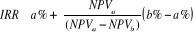

p.122). In brief, there are three steps in determining the IRR. First, a

financial manager should figure out a NPV (a) at one discount rate (a %); then

he/she should find a second NPV (b) at (b %), and as last in the series,

interpolate, that is find the value of the approximate IRR that lies between

the two NPVs, often by means of graph. The formula could result in this way:

(

http://portal.lsclondon.co.uk/resources/course/view.php?id=871).

Concerning the IRR rule, it simply states that whenever an

investment's rate of return is beyond the investor's minimum acceptable rate of

return on a project, it is accepted (Vernimmen et al., 2009, p. 309; Brealey,

Myers and Allen, 2008, p. 123).

Nevertheless, the IRR criterion can undergo some limits

highlighted by financial literature as well. Thus, Brealey, Myers and Allen

(2008) have pointed out numerous problems with the IRR. Indeed, many internal

rates of return for a project can result from lots of changes in the sign of

cash flows. In addition, in case of proposals that are mutually exclusive, the

IRR can probably give a deformed idea of the projects value. As the final

point, the IRR method does not take into account the relative size of projects.

(

http://portal.lsclondon.co.uk/resources/course/view.php?id=871).

To sum it up, over and above of these methods that take into

account one of the core principle of financial theory relating to the

investment decision making, which is the rule of time value of money, there are

other non-discounted cash flows techniques. These tools are worth a visit

now.

2.3.1. b. Non-Discounted cash flows

criteria

Under this section, will be explored the Payback period, the

Profitability index, and the Book or Accounting rate of return methods.

Concerning the Payback period, it can be conceived as the

length of time within a project repays its initial cost. To Droms and Wright,

(2010) the payback rule simply consists of selecting «any project with the

shortest payback period» (Droms and Wright, 2010, p. 191). However,

according to Brealey, Myers and Allen (2008), two examples of thing can go

wrong with the payback technique. First, it does not encompass «all cash

flow after the cut-off date; [secondly, the] «payback rule gives equal

weight to all cash flows before the cut-off date», (Brealey, Myers and

Allen, 2008, p. 121).

With regard to the profitability index, it essentially

provides an answer to the following concern: «How highest NPV are we

getting per pound invested?» Whenever funds are lacking, only projects

that match the insufficient supply of money should be selected. The formula of

the Profitability index is known as followed:

With respect to the accounting rate of return, it should be

mentioned that it amounts to determining the potential book income «as a

proportion of the book value of the assets that the firm is proposing to

acquire». Its formula can be read as followed:

Accounting or Book rate of return = book income ÷ book

assets (Brealey, Myers and Allen, (2008, p. 119). Because the book rate of

return is a sort of means across the total activities of the organisation, we

should not dwell too much upon it. Indeed, this paper's focus rests on the

methods private equity use for investment decision making for start-up

companies.

In any case, we should now turn to explore the financial

literature on recent methods of investment appraisal.

2.3.2 Recent tools of investment assessment: real

options

Three points need to be thought through under this

subdivision. First of all, the concept of real options will be expounded; in

the second place the defining features that make an investment proposal

eligible to real options, and in the third place, what we shall name the

«competitive advantage», which such techniques can procure to private

equity firms in investment assessment of newly created firms.

Expression created by Myers (1977) and, as stated supra, the

notion of real options began to be of any centre of interest of academics in

the 80s. Since that period, there have been a number of conferences and

writings on this topic to such an extent that real options have evolved from a

less valuable topic «to one that now receives active, mainstream academic

and industry attention» (Borison , 2005, p. 17). Be that as it may, real

options method is suitable to any situation where there is a certain amount of

flexibility. In such cases, the venture capitalist is in the same situation as

the financial manager who can increase or decrease his position in a security

given predetermined conditions. A venture capital manager can also be compared

to a financial manager who holds an option. Flexibility of an investment has a

value, the value of the option associated with it. For example, in the field of

industrial investments, real options are equivalent of «the right not the

obligation, to change an investment project, particularly when new information

on its prospective returns becomes available» (Vernimmen et al., 2009, p.

374). This definite property of a flexible investment is referred to as a real

option. Conversely, in the circumstances where it is hard to recognize the

adaptability of an investment, Vernimmen et al., (2009) describe that as

«hidden options» (Vernimmen et al., 2009, p.374).

An investment proposal needs to meet three factors in order

to be qualified to real options. First, there must be some uncertainty

surrounding the project. Secondly, there should be additional information

arriving over the course of time. Thirdly, there must be the possibility to

make significant changes to the project on the basis of this information.

A number of various types of real options can be presented in

investment projects: the option to launch a new project; the option to expand,

reduce or abandon the project; or the possibility to defer the project or delay

the progress of work. According to the first type, Vernimmen et al., (2009) put

forward that it is similar to a «call option on a new business. Its

exercise price is the start up investment, [a significant element] in the

valuation of many companies. In these cases, they are not valued on their own

value, but according to their ability to generate new investment opportunities,

even though the nature and returns are still uncertain.» (Vernimmen et

al., 2009, p. 374).

Finally, the benefits of real options have been highlighted

by Krychowski and Quélin (2010) in the following way: «The main

contribution of RO [Real Option] is to recognize that investment projects can

evolve over time, and that this flexibility has value. Myers (1984) considered

that RO is a powerful approach to reconcile strategic and financial

analysis» (Krychowski and Quélin, 2010, p. 65).

As it has earlier been mentioned in this work, it could add

value to the current literature on methods assessing investment decision by

means of a survey of venture capital firms to find out what techniques they use

in practice concerning investment. Of course, a pilot study has already been

carried out in the fields of venture capitalist investment appraisal in

Australia (

Wright

and Proimos, 2005). But it was, to some extent, narrow since it was focussed on

a specific source of risk named information asymmetry, «which is caused

by lack of information on the part of the VCs, and which can lead to the added

risks of adverse selection and moral hazard» (

Wright

and Proimos, 2005, p. 272). Anyway, what are the bare bones of this literature

review?

2.4. SUMMARY OF ACADEMIC OVERVIEW OF METHODS OF

INVESTMENT ASSESSMENT USED BY PRIVATE EQUITY

Before leaving this chapter, it is useful to summarise the

main tools commonly used by private equity analysts in making investment

decisions, as noted from the literature review.

First, it should be highlighted that there does not appear to

be any previous research on this topic per se in the United Kingdom, and even

abroad. Necessarily therefore, some resort to general knowledge is called for.

There is a widespread agreement among scholars on the meaning of the concept of

private equity. Indeed, private equity is widely defined as equity «that

is not publicly traded and that is used to finance business start-ups,

leveraged buyouts, etc.» (Brealey, Myers and Allen, 2008, p. G-10; Wood

and Wright, 2009, p. 361).

Secondly, investment decision or «capital

expenditure» is the «selection of investment projects» (Arnold,

2008, p. 50). Financing decisions, as opposed to Investment decisions, are

however not within the scope of this piece of research.

Thirdly, there are many techniques used by private equity

specialists in making investment decisions. We weigh up to gather them together

this way: traditional and recent tools. Concerning classic tools, academics

such as Arnold ( 2008, p. 50); Chandra (2008, p. 116) and Vernimmen et al.,

(2009, p. 289) used the sacrosanct principle of time value of money in order to

distinguish discounted cash flows from non-discounted cash flow tools. The

former encompasses the Net present Value (NPV) and its prime competitor, that

is the Internal rate of return (IRR) techniques whereas the latter alludes to

the payback period, the profitability index and the accounting or book rate of

return.

Relating to the recent methods of evaluation of investment

proposal, they consist of real options. Created by Myers (1977), real options

have steadily been on focus in the scholars community, reaching a peak of

interest of both academics and practitioners in the early years of this

21st century as put forward by Borison (2005, p. 17). Because

investment decision is far from being, shall we say, a sort of a

«noli-me-tangere» issue, the flexibility gained from real options

makes a feature of this method. Real options are the possibility to

«modify, postpone, expand, or abandon a project» (Brealey, Myers and

Allen, 2008, p. G-11). Nevertheless, Vernimmen et al. (2009) described the

opposite of real options as «hidden options» (Vernimmen et al. 2009,

p. 374).

|

CHAPTER III RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

|

This chapter intends to answer the following concerns by

turns: what does the concept research means? What is research methodology? What

does research strategy mean? What is the signification of the concept of

research design? What does the notion of data collection methods express and

what is the approach adopted for this work?

3.1. WHAT IS RESEARCH?

In order to comprehend this concept, it would be worth

starting with its negative meaning, in other words, what research is not, or to

be more specific, the wrong meaning of that word. In accordance with this view,

Walliman (2005, p.8) listed four erroneous senses of «research».

First, to him a simple collection of facts or information is nothing but an

«important part of the research». Secondly, according to him,

«moving facts from one situation to another» regardless of

interpretation is far away from being the whole research; it is merely an

additional element of research. Thirdly, he further suggested that research is

not an «esoteric activity, far removed from practical life»; it is an

exploration of the universe, arisen from the strong desire to explain it

instead. Fourthly, research is not a term to «get your produce

noticed»; put it another way, in this case, research is only a result of a

seat-of-the-pants activity.

Probably, the wrong sense of the concept of research has also

something to do with its daily use in such a way that it turns out to be a

virtually commonplace. In fact, there is a sort of ubiquity of the word

«research», since it can be found in the newspapers, on television or

radio throughout wide range of phrases, such as the «findings of market

research companies' surveys», research as support of political decisions,

and «results of research» in the field of advertisement, (Saunders,

Lewis and Thornhill, 2007, p. 4). For clearing up the notion of research, we

should now turn to its proper meaning, or positive sense.

For that purpose, Walliman (2005) have put forward three

distinctive features of the concept research, videlicet a systematic data

collection, a systematic data interpretation, and an unambiguous aim, that is

«to find things out». Research therefore means «something that

people undertake in order to find things in a systematic way, thereby

increasing their knowledge» (Walliman, 2005, p. 5). The concept of

«research» can also be defined as a

«methodical investigation into a subject in order to

discover facts, to establish or revise a theory, or to develop a plan of action

based on the facts discovered» (

http://encarta.m00sn.com/encnet/features/dictionary/dictionaryhome.aspx.).

In a more concise form, Kumar (2008) argued «the search for knowledge

through objective and systematic method of finding solution to a problem is

research» (Kumar, 2008, p. 2).

Having defined what research is it seems now more suitable to

examine the concept of research methodology.

3.2. WHAT IS RESEARCH METHODOLOGY?

To provide an answer to the above question, we might need to

gather first the word methodology per se. In this respect, the term methodology

means «the system of methods followed in a particular discipline» (

http://www.elook.org/dictionary/methodology.html),

or «the study of methods of research» (http

:

//encarta.msn.com/encnet/features/dictionary/dictionaryhome.aspx).

This couple of meaning of the concept methodology only dwell

upon the word method. However, this view of the notion of methodology merely

tends to reduce that concept to one of its components. In fact, the scope of

methodology is wider and more inclusive than that as explained infra.

Concerning the phrase «methods of research», it is

devised as all the techniques that «are used by the researcher during the

course of studying his research problem» (Kumar, 2008, p. 4). Those

techniques could be formed into three groups as Kumar (2008, p. 4)

suggested:

- the first group encompasses data collection methods. They

enable the researcher facing with insufficient availability of data to get

answers that he is after.

- the second set of methods is made up of statistical tools

that help relating data to unknown.

- the third category is concerned with the techniques of

assessing the exactitude of results.

With respect to the expression research methodology, it refers

to the «theory of how research should be undertaken, including the

theoretical and philosophical assumptions upon which research is based and the

implications of these for the method or methods adopted» (Saunders, Lewis

and Thornhill, 2007, p. 602). Once again, research methodology could be viewed

as the whole lot whereas research methods are just components of that entirety.

Therefore, as Kumar (2008) concluded «when we talk of research

methodology, we not only talk of the research methods but also, consider the

logic behind the methods we use in the context of our research study and

explain why we are using a particular method or technique and why we are not

using others so that research results are capable of being evaluated either by

the researcher himself or by others» (Kumar, 2008, p. 5).

Having highlighted that, research methodology does obviously

raise the following three overriding concerns such as:

- Research philosophy or strategy

- Research Designs and

- Data collection methods.

Any single aforementioned issue is worth expounding by

turns.

3.3. WHAT IS RESEARCH PHILOSOPHY OR

STRATEGY?

To start with, a terminological precision needs to be

stressed. It is about research philosophy and research strategy. Some academics

make use of the first to allude to the second actually. For instance, Saunders,

Lewis and Thornhill (2007, p. 102), regarding what they named «research

onion», they argued that research philosophy, located in the first layer

from the surface, includes the following sets of idea: positivism, realism,

objectivism, subjectivism, interpretivism, pragmatism, radical humanist,

radical structuralist, functionalist, and interpretative. However, to their

viewpoint, research strategy encompasses experiment, survey, case study, action

research, grounded theory, ethnography, and archival research. Nonetheless, to

others the first group constitutes research strategy whilst the second should

be called research design (Bennison, 2006).

As a matter of fact, what precedes does give an account of

just a difference of terminology, because when it comes to look at the

components of each concept, we could easily conclude that they are alike. In

any case, throughout this paper we should refer to the concept of research

strategy to allude to research philosophy. Notwithstanding, when it will come

to talk about what Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill (2007, p. 102) named research

strategies, we should refer to as research design instead in order to avoid

being muddled.

Having noted that, it should be stated that research strategy

rests on the idea that it determines the basic philosophy whereby a subject

could be approached. There are a number of abstract concepts that form research

strategy as said supra, but we will only examine three out of the list, namely

axiology, epistemology, and ontology.

3.3.1. Axiology as research strategy

From Greek «axia», that is value and

«logos», that means study of, axiology can thus be defined

as that subdivision of philosophy that concerns with the study of values (

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Axiology).

The usefulness of axiology as strategy of research has been

highlighted by Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill (2007, p. 110). They argued that

the values of the researcher irrigate all his work. For example, they suggested

that a selection of a given topic rather than another shows the researcher

believes the chosen topic is much more interesting. However, apart from

axiology that concerns the values of the researcher and those of the people he

interacts with, the researcher needs to be aware of the scope and nature of the

knowledge he is in search of. Epistemology meets this want.

3.3.2. Epistemology: a research strategy

The word epistemology derives from the Greek

«episteme», signifying knowledge, science, and «logos»

meaning study of (

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epistemology).

Epistemology, therefore, is a division of philosophy that deals with the nature

and scope of knowledge.

Thanks to epistemology, the researcher could differentiate

between belief and opinion. In short, there are a number of epistemological

stances that a researcher can adopt. If he or she leans towards the application

of natural sciences, he or she will be deemed to adopting positivism as

epistemological position. But, since the complexity of the social world of

business and management is reluctant to a «series of law-like

generalisations» that for example physical sciences allow (Saunders, Lewis

and Thornhill, 2007, p. 106), interpretivism would be resorted to instead. What

do we think about ontology then?

3.3.3. Ontology: a strategy of research

The concept of ontology comes from Greek «ov,

genitive» meaning of that which is, and «logia», that is study,

science, or theory, (

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ontology).

Part of metaphysic, ontology is the philosophic activity that concerns with the

existence of entities.

Boosted by the significance of the word ontology, it should

moreover be noted that as a research strategy, it implies two distinct

positions. First, the researcher could adopt an objectivist posture. This

ontological stance advocates, «things exist in reality external to

people» (Bennison, 2006).

Secondly, the subjectivism, also known as constructionism

(Remenyi et al., 1998, p.35), refers to the reverse order of objectivism. To be

more specific, a subjectivist researcher claims, «social phenomena are

created from the perceptions and consequent actions of social actors»

(Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill, 2007, p. 108).

From all what precedes, we could get a clear insight into the

concept of research strategy and shall now move on gathering the phrase of

research design.

3.4. WHAT ARE RESEARCH DESIGNS?

Alongside the research strategy, research designs appear as a

landmark of the research methodology insofar as it is a source of benchmark for

data collection. We, thus, should have a look at different research processes

before examining the various sorts of research designs as such.

3.4.1. Research processes

As far as research processes are concerned, two major types of

reasoning are on focus:

- Inductive reasoning and

- deductive reasoning.

Relating to inductive reasoning, Walliman (2005) suggested

that it consists of the «inference of a general law from particular

instances. Our experiences lead us to make conclusions from which we

generalize» (2005, p. 433). The inductive reasoning is also called

«bottom-up» approach (Bennison, 2006).

With regard to the deductive reasoning, or «top-down

approach», it works anticlockwise to that of the inductive does. In this

view, its starting point is a theory or a general idea, which gradually becomes

narrower down to hypotheses. These hypotheses are to be confirmed or not by

data collected. Be that as it may, the framework of data collection and

analysis could be in the form of some sorts of research designs.

3.4.2. Research designs

Under this subdivision, will be by turns examined the

following wide range of research designs:

- experimental design

- cross-sectional design

- longitudinal design

- case study design, and

- comparative design.

With respect to the experimental design, its aim is to examine

causal relationship effect (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill, 2007, p. 136). There

are two types, namely the classic and the quasi-experimental design. Concerning

the former, two groups on focus are established: a treatment group and a

control group. Then people are randomly divided up to each group. There is a

pre-text of each group before the experiment and at the end of the day, there

is as assessment of dependant variable before and after the experiment.

However, in case of quasi-experiment, there is no control group and the

independent variable is measured before and after.

Concerning the cross-sectional design, it is often called

«social survey design» because it does resort to survey strategy

(Easterby-Smith, Thorpe and Lowe, 2002). According to Kumar (2010, p. 107), the

cross-sectional design, also referred to as «one shot or statues

study» constitutes the most famous design in the social sciences. Its

objective is to depict variation between people for example, and in a single

point in time. Also, the cross-sectional design is aimed at describing the

impact of a fact or an occurrence that can be observed. Moreover, it intends to

give an account of in what way factors are connected within an organisation as

suggested by Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill, (2007, p. 148).

With regard to the longitudinal design, its aims are to track

changes over time instead. Therefore, in accordance with that research design,

«the study population is visited a number of time at regular intervals,

usually over a long period» as claimed by Kumar (2010, p. 390) and Kumar

(2008, p. 10). The longitudinal research design has the distinctive feature of

allowing the researcher to manage variables that he concentrates mainly on as

long as there is no influence of research process per se on them as argued by

Adams and Schvaneveldt (1991).

Concerning the case study design, Robson (2002) conceives it

as a «strategy for doing research which involves an empirical

investigation of a particular contemporary phenomenon within its real life

context using multiple sources of evidence» (Robson, 2002, p. 178). In

2003, the relevance of the concept of context has been put forward by Yin

(2003). In fact, according to him, there is not a real watertight compartment

between the phenomenon that is subject matter of the study and the context

within which it is carried out. There are various sorts of case study designs.

When a case study aims at the veracity of a hypothesis, it is called a critical

case. However, when its purposes are to deeply understand a particular case on

the one hand, and closely investigate an issue which has been neglected on the

other hand, it is appropriately named unique case then. With respect to the

unique case study, Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill (2007) have suggested

triangulation as a method of data collection. The notion of triangulation is

regarded as «the use of different data collection techniques within one

study in order to ensure that the data are telling you what you think they are

telling you.» (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill, 2007, p. 139). For instance,

it is possible to value a questionnaire as a technique of gathering

quantitative data thanks to semi-structured group interview. Concerning the

unit of analysis, Yin (2003) distinguishes «embedded case study» from

«holistic case study». The former consists in investigating some

sub-units of a firm, such as departments or teams whilst the latter intends to

examine the whole organisation instead.

Relating to the comparative design, it tends to give accounts

for similarities or differences in order to encourage comprehension. In doing

so, Bennison (2006) suggested the recourse to cross-sectional techniques like

cross national, cross cultural, cross organisational, cross cultural, cross

divisional methods.

In any case, whatever the research designs might be, the

researcher needs to collect data.

3.5. WHAT ARE DATA COLLECTION METHODS?

To start with, it is worth saying that data can be described

as «a series of facts that have been obtained by observation or research

and recorded» (Bocij et al., 2006, p. 794). Concerning data collection

methods, they could be identified according to the type of research strategy or

design the work has adopted. Under this section, shall we say, the

«Ariadne's thread» is to distinguish depending on whether

quantitative, or qualitative strategy is on focus.

In case of a quantitative strategy, associated with an

experimental design, the researcher has to rely, to a greater extent, on

numerical data. Furthermore, he or she will resort to a «structured

approach in order to reduce [his or her] influence on the research»

(Bennison, 2006).

In the event of qualitative strategy, connected with case

study design, the researcher will have to «use open ended methods of data

collection to capture a wide variety of opinions» ( bennison, 2006).

Anyway, data collection methods, such as structured

observations, interviews, and questionnaires sound more appropriate to

quantitative strategy. Whereas observation, semi structured Interviews,

questionnaires, focus or discussion groups appear to be suitable to qualitative

methods. Relating to questionnaires as method of data collection, it has been

devised as «a general term [including] all techniques of data collection

in which each person is asked to respond to the same set of question in a

predetermined order» (De Vaus, 2002). There are a wide a range of kinds of

questionnaires depending on the way they are administered. When a questionnaire

is filled by respondent himself, it is known as «self-administered»

questionnaire. This sort of questionnaire can be electronically answered

through internet or intranet, or mailed to respondent who will return it after

completion. Conversely, whenever a questionnaire is answered during a physical

contact with the respondent, it is named «interviewer-administered»

questionnaire as claimed by Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill, (2007, pp. 356-357).

Overall, what is the approach adopted for this study?

3.6. APPROACH ADOPTED FOR THIS STUDY

First of all, this paper does take into consideration some

research strategies like axiology, ontology and epistemology. Axiology has been

taking into account upstream from the selection of this topic. Actually,

because it seems not to exist prior research on the techniques of investment

appraisal used by private equity firms per se, we were led to all the relevance

of this exploratory research. Furthermore, in the course of surveying the

previously mentioned firms, we should be aware of their values and would be

keen to admit them without passing any sort of judgment as demands the basic

requirement of axiology strategy. Epistemology, and to be more accurate,

interpretivism is considered throughout this work due to the specificity of

business study; so, the qualitative philosophy of research will be utilised in

order to interpretate, understand and conduct a thick description of reality

of tools of investment appraisal used by private equity. Ontology is concerned

here insofar as we should bear in mind enough objectivity in making analysis of

data collected.

Secondly, as far as research design is concerned, this paper

has opted for the cross-sectional design as long as patterns of association

will be looked for and data collection will be based on electronic

questionnaires.

|

CHAPTER IV FINDINGS AND DATA ANALYSIS

|

The purpose of this chapter is to give an account of data

collected in order to provide answers to the research questions that pertain to

this work. To do that, as we have highlighted supra, questionnaires were opted

for as methods of collecting data. As a matter of fact, 25 venture capital

firms have received an electronic questionnaire via Survey Monkey. Only 13,

that is almost half of them have provided responses, which have been deemed as

a somewhat representative sample of the threshold population. The first task

consists in analysing answers given by those respondents and the second task

has something to do with summarising findings. Prior to these activities, it is

worth reminding that ethical considerations, such as anonymity are taken into

account in this work; thus, neither questions relating to personal details of

the respondent nor the results of this study will be published.

4.1. ANALYSIS OF DATA

In order to get a sound insight into the data collected within

the framework of this study, both the display and analysis approach of Miles

and Huberman (1994) have been adopted. Relating to data display and analysis in

this work, it deals with an organisation and comment of data that are primarily

related to research questions into diagrams. We will, therefore, give an

account of the data collected compared with the following concerns:

- What are the classic methods of analysis used in practice by

private equity firms in capital budgeting for start-ups devoid of any

flexibility?

- What is the recent practice of private equity analysts in

respect to techniques of start-ups companies flexible capital budgeting?

- What can we learn from an inquiry into the practice of

venture capitalist in the field of determining the investment decision for

newly created companies?

- Are the findings from the investigation into the way the

venture capitalists make investment decision in practice profitable to both the

main players, namely venture capital firms and new entrepreneurs?

4.1.1. Traditional tools of analysis used in practice

by venture capitalist in making investment decision

We can learn from information gathered that Private equity

firms, whatever industries they belong to (as shown on the first graph

hereafter), do utilise classic methods for evaluating proposals. Those

techniques include discounted cash flows methods such as the Net Present Value

and the Internal Rate of return. Furthermore, venture capitalist does also

resort to non-discounted cash flows methods, notably the payback rule, the

profitability index and the accounting or book rate of return in making

investment decision. These successive graphs are therefore an illustration of

that state of affairs.

The above column chart indicates the 07 sorts of industries

within the dozen of Private equity firms that have been surveyed could probably

invest. On the whole, it is clear that Private equity analysts rather preferred

health care and Consumer goods and services investment proposals to any other

out of the list.

In fact, there was a sharp identical percentage, notably 33.3

percent, in the number of private equity, which could happily grant funds to

technology industries start-ups as well as financial ventures. Concerning the

former, telecommunication sector itself, included fixed line and mobile, and

information technology were parts of technology sector. Relating to the latter,

real estate, financial services per se, figured in financial component part. In

addition, there was another identical proportion in the number of industry

sectors selected by private equity organisations. In effect, approximately 8

percent of private equity analysts were choosing to spend money on basic

materials, and oil and gas sectors likewise. Basic materials referred to

chemicals, forestry and paper, industrial metals and mining, whilst oil and gas

comprise alternative energy, oil and gas producers, and oil equipment services

and distribution.

However, only probable acceptances of industrial investment

projects represented a sixth of the number of private equity organisations on

focus here. Industrial proposals alluded to aerospace and defence, construction

and materials, electronic and electrical equipment, engineering, general

industries, support services and transportation.

To sum up, it can be seen that Health care industry sector

constituted the most popular choice out of the seven kinds of sectors of

industry. Notwithstanding, private equity analysts did utilise classic methods

for appraising venture start-up companies, regardless of the sector of industry

they belonged to as demonstrated infra.

The above pie chart displays information about the percentage

of techniques that take into consideration the sacrosanct principle of the time

value of money in making investment decision for new ventures. Overall, it is

obvious that the Internal Rate of return was the discounted tools of analysis

most used by private equity in making investment appraisal.

As a matter of fact, the percentage of private equity firms

that resorted to the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) constituted roughly the

double of the proportion of those that utilised the Net Present Value (NPV),

namely almost 67 percent.

To conclude, there is no doubt that the Internal rate of

Return was by far the most popular method used by private equity analysts for

making investment decision for start-ups. It should be worth moving on the

question of what private equity firms think about these two classic discounted

cash flows methods.

This stacked bar chart illustrates the views that surveyed

private equity analysts took about the utility of a couple of discounted cash

flows methods for capital expenditure of newly created firms. Generally

speaking, the IRR technique did attract numerous private equity analysts.

In fact, as far as one of the overriding rules of financial

theory is concerned, namely the time value of money, roughly half of the

venture capital firms analysts did tend toward the use of the IRR method.

Although there was one skipped question concerning this category, it did not

affect the final results in terms of dominance of the IRR technique. Indeed,

the results relating to NPV as discounted cash flows were completed and less

than half of respondents were in favour of that method. Conversely, 6 among 12

private equity firms analysts did prefer IRR technique. The unique assumption

that we could make is that if the participant who refrained from answering to

that question selected any option apart from «agree», the superiority

of IRR would still be valid.

Moreover, the trend of the prime importance of the IRR was

further strengthened by the number of people who strongly disapproved the NPV

as a practical means of evaluating start-ups investment proposals. Actually,

only one venture capital analyst disagreed with the use of IRR whereas two

people did not share the view that the NPV rule does recognise the principle of

the time value of money.

With regard to the point of mutual exclusive proposals and the

use of the NPV technique, it is clear that there was an enormous increase in

the number of neutral participants, approximately 60 percent. Furthermore,

there was a slight drop in the number of approvals of NPV as one useful

technique of making investment decision for start-ups in case of non-concurrent

projects.

In conclusion, regarding the opinion of private equity

analysts about the usefulness of discounted cash flows tools of evaluating

start-ups capital expenditure, the IRR method was more popular than its

competitor, namely the NPV, notwithstanding one skipped question in the number

of respondents related to the IRR as a discounted cash flows technique. This

trend has been confirmed even in a more general aspect as shown in the next

diagram.

The pie chart that appears at the bottom of the previous page

displays information about the percentage of choice of two discounted cash

flows methods for appraising start-up companies. On the whole, the gap in the

selection between the IRR and NPV method by private equity analysts was not

that large.

As a matter of fact, more than the half of the participants

were attracted by the IRR as a technique of evaluating capital budgeting for

newly created ventures. To be more specific, 53.8 percent of private equity

firms did prefer IRR method to the NPV technique.

Nonetheless, NPV as a tool of analysis of investment appraisal

of start-up firms was only selected by 46.20 percent of private equity firms

that took part in this survey.

Finally, it is obvious that private equity analysts do prefer

the IRR method to the NPV tool when it comes to make investment decision for

start-up companies. These results seemed far too much similar to the findings

of Graham and Harvey (2001) released 10 years ago. Their results showed that

«74.9% [Chief Finance Officers] always or almost always use the internal

Rate of return», which was roughly 1% more than those who referred to the

Net present value criterion (Graham and Harvey, 2001, p. 193). Nevertheless,

some distinction still needs to be drawn since Graham and Harvey (2001) did

survey only Chief Finance Officers of 4,400 American firms, with the exception

of Venture capital organisations. We should now move on finding out what the

information collected reveals with respect to the use of non-discounted cash

flows methods for capital expenditure of new ventures.

This line graph demonstrates the number of private equity

firms that utilised non-discounted cash flows methods in making investment

decision for start-up companies. As far as the overall trend is concerned,

there was a gradual decline in the number of users of methods, which did not

take into consideration the sacrosanct rule of the time value of money in

making capital expenditure decision for start up companies.

At the beginning, among the 13 private equity analysts who

took part in this survey five confirmed that they utilised the payback rule as

a non-discounted cash flows technique of evaluating capital budgeting proposals

for newly created ventures. That was a sharp percentage of 41.7.

In contrast, 33.30%, that is to say four respondents chose

the profitability index; only a quarter was interested in the accounting or

book rate of return as a criterion of an investment decision into start up

firms' proposals. Unfortunately, there was one skipped question with respect to

the issue of the use of non-discounted cash flows methods for appraising

capital budgeting of start up companies; therefore, the above-mentioned

proportions are no more and no less symptomatic of 12 effective respondents.

In a completely different respect, it has been argued that,

although it was in a more general perspective, among non-discounted cash flows

methods of capital budgeting the accounting or book rate of return looks like a

poor relation with approximately 12 percentage of use by Chief Finance Officers

(Graham and Harvey, 2001, p. 193). This trend has been somewhat confirmed here

as long as only 25 percent of private equity analysts did say they resorted to

that technique of capital budgeting for start up companies.

By way of conclusion, it can be seen that the payback rule was

the most attractive technique among private equity organisations as far as

non-discounted cash flows techniques that they resorted to in making investment

decision for start-up companies were concerned. We should now examine the

viewpoint of these private equity analysts about the realistic aspect of the

previously mentioned non-discounted cash flows methods for evaluating

investment decision for start up organisations.

The above chart constitutes an illustration of information

concerning the perception that 13 private equity firms had about the practical

aspect of three non-discounted cash flows tools of analysis for start-ups'

capital expenditure. On the whole, it is obvious that point of views did not

wildly fluctuate between the payback rule, the profitability index and the

accounting or book rate of return.

Without any doubt, about 50 percent, in other words 6 out of

12 ( because there was one skipped question) private equity firms thought that

the payback rule, as a method for evaluating investment decision for newly

created ventures, was practical.

In addition, 4 private equity analysts out of 12 who really

did answer this question, were attracted by the realistic feature of the

accounting or book rate of return. This number stood for roughly 33 percent of

the whole responses relating to the issue of the practical characteristic of

non-discounted cash flows techniques of appraising start ups capital budgeting.

Conversely, the non-discounted cash flows method of capital

expenditure for start-up organisation regarded as the least realistic, turned

out to be the accounting or book rate of return. Oddly, only a sixth of private

equity firms thought that that capital budgeting technique was practical for

start up companies whilst a quarter previously claimed its utilisation in

accordance with the results of the previous line graph that appeared at the

bottom of page 34 of this work. Probably, there were other bases of that use,

which the participants did not specify even though they have been suggested to

do so within the framework of the questionnaire.

To sum up, it is clear that when it came to make investment

decision for start up companies based on non-discounted cash flows methods,

private equity analysts did consider the payback rule as more realistic than

the two other techniques, namely the accounting or book rate of return and the

profitability index. This work will hereafter inquire data in comparison with

start up companies' capital budgeting where proposals cannot be adapted to a

new situation.

This bar chart is a display of information about the best

techniques that private equity analysts referred to when it comes to make

capital budgeting decision that is devoid of any flexibility for newly created

ventures. In general, for that purpose, all participants tended toward choosing

among one of these methods, namely the profitability index, the payback period,

and the NPV, excepted for the IRR.

As a matter of fact, a third of private equity analysts did

prefer the Net present Value method in making non flexible capital budgeting

decision for start up firms.

However, according to a quarter of private equity firms, the

accounting or book rate of return was the best tool of analysis that they

referred to in making non flexible investment decision for start up companies.

Moreover, the same proportion considered the profitability index technique and

the payback period as the best method of analysis on the subject

aforementioned. Nevertheless, the IRR technique looked like a poor relation in

the eyes of private equity analysts. In fact, none of the 13 private equity

analysts who took part in this survey regarded this method as a useful

technique in making non-adaptable investment decision for newly created

ventures.

In summary, when it comes to make start up companies

investment decision devoid of any flexibility, a simple majority of 4 out of 13

private equity analysts did prefer relying on the NPV technique rather than

others classic methods such as the payback rule, the profitability index, and

the accounting or book rate of return. The comment on this trend is that one of

the Net Present Value's principal challengers, the Internal rate of Return

method, has to say the least been downgraded, even ignored by the respondents.

The peculiarity of these results stands out against prior research on the use

of traditional methods of making investment decision in corporate finance as

shown by scholars such as Graham and Harvey (2001, p. 193). Having said that,

what practical tool of analysis do private equity firms resort to in making

flexible investment decision for start-ups organisations?

4.1.2. Recent technique of analysis used in practice

by venture capitalist in making flexible and reversible investment decision for

start-up companies

The aim of this subdivision is to describe and explain the

points of view of 13 private equity analysts with regard to the tools they use

in making flexible investment decision for newly created ventures. Because

capital budgeting seems far from being a commonplace decision on the one hand,

and completely lacking of adaptability to new circumstances on the other hand,

the financial theory developed by scholars like Myers (1977), Borison (2005, p.

17), Vernimmen et al., (2008, p. 374), Krychowski and Quélin, (2010, p.

65) has put forward real options. This work will thus make some incidental

comparisons with previous studies. Boosted by what precedes, we should

therefore examine viewpoints of private equity analysts as successively shown

in the following figures.

|

Methods used by private equity analysts in making

flexible investment decision for start-ups companies

|

Response count from 8 private equity analysts

|

Percentage

|

|

IRR

|

2

|

25%

|

|

NPV

|

3

|

37.5%

|

|

Real options

|

1

|

12.5%

|

|

The accounting or book rate of return

|

1

|

12.5%

|

|

The payback rule

|

1

|

12.5%

|

|

The profitability index

|

1

|

12.5%

|

Table 1: What do you resort to in making flexible

investment decision for start-ups organisations?

The above table is a display of 08 out of 13 viewpoints of

private equity analysts (as long as there were 5 skipped questions) with

respect to the methods that they resort to when the investment projects

submitted to them by start-ups are adaptable and / or reversible. Broadly

speaking, it can be noticed that their opinions were eclectic enough.

First of all, 3 over 8 private equity analysts did maintain

that they had recourse to the Net Present Value method of capital budgeting for

newly created ventures. That figure stood for 37.5 percent and was the most

used technique as far as private equity firms were concerned when it comes to

make flexible investment decision for start-up companies. Moreover, a quarter,

in other words 25 percent of these private equity analysts has claimed an

exclusive recourse to the Internal Rate of Return.

However, only 12.5 percent of the respondents said that they

utilised one of the following tools of analysis in assessing start-ups capital

budgeting : real options, the accounting or book rate of return, the payback

rule, and the profitability index.

To conclude, the findings regarding the techniques that

private equity analysts do have recourse to in evaluating start-ups flexible

capital expenditure clearly demonstrate the prime importance of NPV method over

others. This result is surprising at least for a couple of reasons. In the

first place, the shortcomings of the NPV tool of analysis per se have been

deplored in a numerous financial academic writings as noted earlier in this

work on page 10. Secondly, Net Present value does ignore «the value of

managerial flexibility, in other words the options that the manager can exploit

after an investment has been made in order to increase its value»

(Vernimmen et al., 2009, p. 297). In the face of this situation, there is no

need to make a mountain out of a molehill as long as private equity analysts

should refer to real options in order to adjust the aforementioned NPV's

restricting flaws.

Table 2: How do you rate Real options relating to

making better flexible capital expenditure decision for start-up

organisations?

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

8

|

9

|

10

|

Rating average

|

Response

count

|

|

Real options provides us with a better adaptability in the

management of proposal

|

0.0%

(0)

|

0.0%

(0)

|

0.0%

(0)

|

8.3 %

(1)

|

50%

(6)

|

16.7%

(2)

|

0.0%

(0)

|

16.7%

(2)

|

0.0%

(0)

|

8.3% (1)

|

6.00

|

12

|

The table that comes into view at the bottom of the previous

page displays information about the rating scale of real options as a technique

of appraising flexible start-up firms' capital expenditure as far as private

equity analysts are concerned. Overall, it is obvious that there was a

substantial participation on behalf of private equity analysts regarding that

question because 12 out of 13 private equity firms did give an effective

response to that issue.

To start with, half of private equity analysts set value on

real options as a technique whereby they evaluated flexible proposal from

start-up companies. Indeed, on the scale of 10, 50 percent of respondents gave

a rate of 5 to real options like a satisfactory tool of assessing reversible

and / or flexible start-ups investment projects.

Furthermore, there was a double similarity in the number of

respondents who concurred that real options were a helpful technique for making

better flexible investment decision. Firstly, 8.3% of private equity analysts

ascribed a rate of 4 over 10 to real options on the one hand, and a rate of 10

over 10 to real options on the other hand. The latter rate sounded somewhat

astonishing and probably derived from the unique private equity analyst who

pretended to refer to real options method according to the previous table.

Secondly, roughly twice of the previous percentage, (in other words 16.7%)

regarded real options as a useful method for evaluating start-up companies'

flexible capital budgeting. In accordance with this viewpoint, 2 people gave a

rate of 6 over 10 and 8 over 10 to real options respectively.

However, the scale rates of 1 to 3 as well as 7 have not been