|

|

Ministry of Higher Education, Scientific Research, and

Technology

University of Manouba

Faculty of Letters, Arts, and Humanities,

Manouba

|

Heritage Language Maintenance

among the Berbers of Zrawa

(Southern Tunisia): An Exploratory

Study

Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the

requirements of the Master's

Degree in English Linguistics

Student: Mohamed Elhedi Bouhdima Supervisor: Dr. Faiza

Derbel

2017

i

Dedication

To my mother and father.

To my brothers and

sisters.

To my friends.

To all those who love me and believe in

me.

ii

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my advisor, Dr. Faiza Derbel, for her

direction, support, and valuable comments.

I would like to thank all the participants who asked other

individuals to take part in the study.

I would like to thank my parents, brothers, and sisters for their

endless love, encouragement, and support.

I would like to thank all my friends for their encouragement,

support, and belief in me.

iii

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to investigate the maintenance of

Amazigh (Berber) language among the Imazighen (Berbers) of Zrawa, a village in

the south-east of Tunisia. The data for the present study were collected during

the month of February 2017 using the mixed methods approach. A questionnaire,

semi-structured interview, and participant observation were used to collect

data. The questionnaire was initially administered to 53 Imazighen from various

age groups, various occupations, and both genders. Subsequently, 11 were

interviewed after filling out the questionnaire in order to generate in-depth

data concerning certain topics included in the questionnaire and to collect

data about topics which were not investigated in that questionnaire. The

participant observation took place during ten visits to Zrawa, with each visit

taking approximately eight hours. The reason behind the use of participant

observation was to gather data about the geographic concentration of the Zrawa

Amazigh community, including the language used within the community. Results

from the study indicate that the factors contributing to AL maintenance in

Zrawa are: (a) the geographic concentration of the Amazigh community, (b) the

essential role of Amazigh families, (c) Imazighen's positive attitudes towards

the Amazigh language, and (d) the perceived close relationship between Amazigh

language and identity.

iv

Table of Contents

Dedication i

Acknowledgements ii

Abstract iii

Table of Contents iv

List of Figures viii

List of Abbreviations ix

Chapter One: Introduction 1

1.0. Introduction 1

1.1. Background to the study 1

1.2. Context of the study 4

1.3. Rationale and objectives of the study 8

1.4. Significance of the study 8

1.5. Design of the study 9

1.6. Overview of the study 9

Chapter Two: Literature Review... 11

2.0. Introduction 11

2.1. The Importance of Language Maintenance 11

2.2. Language maintenance research 12

2.3. Factors contributing to LM 15

2.3.1. Geographic concentration of speakers 15

2.3.2. Family . 16

2.3.3. Language attitudes of speakers 18

2.3.4. Aspects of the language-identity relationship... 20

2.3.5. Government policy 22

2.3.6. Education 23

v

2.3.7. Religion 24

2.3.8. Media 24

2.3.9. Socio-cultural organizations 25

2.3.10. Urban-rural nature of setting... 26

2.4. Factors facilitating LS 27

2.4.1. Family . 27

2.4.2. Prestige 28

2.4.3. Length of residence 29

2.4.4. Access . 29

2.4.5. Employment 29

2.4.6. Migration 31

2.4.7. Government policy 31

2.4.8. Media .. 32

2.4.9. Education 32

2.5. Conclusion 33

Chapter Three: Methodology 35

3.0. Introduction 35

3.1. The methodological approach for the study 35

3.2. Description of participants 36

3.2.1. Sampling methods 37

3.2.2. Characteristics of the participants 38

3.3. Description of data collection instruments 38

3.3.1. Participant observation 38

3.3.2. The questionnaire 38

3.3.3. The semi-structured interview 39

vi

3.3.3.1. Question type 39

3.3.3.2. Question topics 39

3.4. Data collection procedures 40

3.4.1. The participant observation 40

3.4.2. The questionnaire 40

3.4.3. The semi-structured interview 40

3.5. Data analysis techniques 41

3.5.1. Analysis of qualitative data 41

3.5.2. Analysis of quantitative data 42

3.6. Conclusion 42

Chapter Four: Results and Discussion 43

4.0. Introduction 43

4.1. Role of the geographic concentration of Zrawa Amazigh

community 43

4.2. Role of Zrawa Amazigh families 49

4.3. Role of positive attitudes towards AL 57

4.4. Role of the perceived link between Amazigh language and

identity 63

4.5. Conclusion 67

Chapter Five: Conclusion 69

5.0. Introduction 69

5.1. Summary of major findings 69

5.1.1. Role of the geographic concentration of Zrawa Amazigh

community 69

5.1.2. Role of Zrawa Amazigh families 69

5.1.3. Role of positive attitudes towards AL 69

5.1.4. Role of the perceived link between Amazigh language and

identity... 70

5.2. Implications for the study 70

5.3. Contributions of the study 71

vii

5.4. Limitations of the study 71

5.5. Recommendations for further research 72

References 73

Appendices 81

Appendix A. The English version of the questionnaire 81

Appendix B. The Arabic version of the questionnaire 83

Appendix C. General characteristics of male participants 85

Appendix D. General characteristics of female participants 86

Appendix E. The interview questions 87

Appendix F. Details about the interviews 88

Appendix G. Transcription symbols 89

Appendix H. A translated transcript of the interview with Mr.

Alaa 90

Appendix I. Map of the Amazigh-speech zones in Tunisia based on

Pencheon (1968) 94

Appendix J. Map of the Amazigh-speech zones in Tunisia based on

Maamouri (1983) 95

Appendix K. Location of Zrawa in Gabes (Tunisia) 96

viii

List of Figures

Figure 4. 1: Map of (New) Zrawa 43

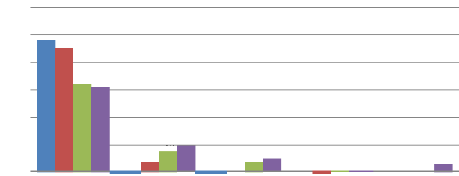

Figure 4. 2: Results of statement 7 on speech

accommodation 47

Figure 4. 3: Results of statements 1, 2, 3, and

4 on language attitudes 58

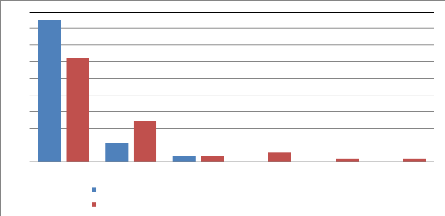

Figure 4. 4: Results of statements 4 and 5 on

the link between Amazigh language and

identity 63

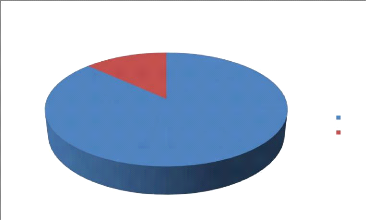

Figure 4. 5: Results of question

3 about the link between Amazigh language and

identity 66

ix

List of Abbreviations

AL: Amazigh Language HL:

Heritage Language LM: Language Maintenance

LS: Language Shift

TA: Tunisian Arabic

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 1

Chapter One: Introduction

1.0. Introduction

This chapter is an introduction to the study. It starts by

presenting the background, the setting and the rationale of the study. It also

highlights the significance of the study. Besides, it describes the design of

the study. The chapter ends by providing an overview of the study. 1.1.

Background to the Study

Maamouri (1983a, pp. 11-19) states that the

linguistic situation of post-colonial Tunisia is complex and argues that six

languages are currently used in Tunisia: French, French-Arabic, and four

varieties of Arabic: (a) Classical Arabic, which is the «only pure form of

the language» (p. 15); (b) Modern Standard Arabic, which is less formal

than Classical Arabic;

(c) Tunisian Arabic; and (d) Educated Arabic, which is «a

form of `simplified Modern Standard Arabic (arabiya mubassata) and a form of

`elevated' Tunisian Arabic (darija muhathaba) or both at the same time»

(p.17). French is used in education whereas French- Arabic is used by students

in settings other than the classroom and by government officials, members of

the professions, and other administrators, in informal situations. As to

Classical Arabic, it is used in Qur'an recitations, prayers, religious sermons

and talk, and literary creation and criticism. Modern Standard Arabic is used

in mass media, political speeches, modern plays, novels, literary magazines and

lecture, and primary and secondary schools. As for Educated Arabic, it is

mainly spoken by educated Tunisians and used in politics. Tunisian Arabic (TA)

is the dominant language in the country. It is less formal than Classical

Arabic and Modern Standard Arabic.

As to the Amazigh language (AL), Maamouri (1983a, p. 14)

states that it is a marginalized minority language in Tunisia. This implies

that it has a number of characteristics. Indeed, Simpson (2001, pp. 579-580)

lists 13 characteristics of a minority language. In this context, I will

mention only four which, I think, are the most relevant to the plight of AL in

Tunisia.

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 2

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 3

First, a minority language lives in the shadow of a culturally

predominant language. Actually, it can be concluded from the use of Arabic in

almost all settings that AL lives in the shadow of Arabic. Second, a minority

language is not used in formal settings such as administration, education, and

mass media; but rather, confined to such domains as the home. As mentioned

above, Arabic, but not AL, is used in key domains such as education, politics,

mass media, and religion. However, as Maamouri (1983a, p. 14) states, in the

Tunisian Amazigh villages, AL is the only language used within Amazigh

families. Third, bilingualism is common among the speakers of a minority

language. At least, this is the case of the Amazigh-speaking inhabitants of

Zrawa, the focus of the actual study (see sections 1.2 and 4.1).

Finally, a minority language may have no standardized form. As Ennaji (2005, p.

73) acknowledges, AL is neither standardized nor codified. In a nutshell, AL is

neither the majority nor the official language of Tunisia. Indeed, as

aforementioned, TA is the dominant language whereas the official language, as

Maamouri (1983b, p. 147) acknowledges, is Modern Standard Arabic.

It appears that not being the official or majority language of

the country gives AL the aspect of a heritage language. As Cummins (2001)

asserts, «in a general sense, the term heritage languages refers

to languages other than the official or majority languages of a country»

(p.619). Explaining the meaning of the term «heritage languages»,

Cummins (200,

p. 619) states that it is meant to acknowledge that these

languages constitute important aspects of the heritage of individual children

and communities and are worthy of financial support and recognition by the

wider society. This may be relevant to AL. Indeed, Ennaji (2005, p. 74) states

that AL is a basic component of Moroccan and North African culture. Ennaji

(2005, p. 76) also states that AL is one of the oldest African languages in the

sense that it is the mother tongue of the indigenous inhabitants of North

Africa. In a similar vein, Maamouri (1983a, p. 14) acknowledges that AL is the

indigenous language of Tunisia.

Taking together the suggestion that AL is a heritage is a

heritage, the acknowledgement that AL is the indigenous language of Tunisia,

and the fact that the languages spoken by Amerindians, who are the indigenous

people of the United States of America, are identified by Fishman (2001, pp.

83-83) as indigenous heritage language leads to the deduction that AL is an

indigenous heritage language. Finally, it is worth noting that heritage

languages have been referred to using different terms. As Cummins (2001, p.

619) states, the terms «ancestral», «ethnic»,

«immigrant», «international», «minority»,

«non-official», «third» (after English and French),

«world», «community languages», and «mother tongue

teaching» have all been used in different times and in different countries

to refer to heritage languages.

Returning to the plight of AL in Tunisia, the regression of

this language has been due to a number of factors. As Maamouri (1983a, p.14)

states, AL has gradually regressed due to the rapid development of the

educational system and the general spread of modern mass media. For Pencheon

(1983, pp. 31-32), the regression of AL in Tunisia is attributed to the

following factors. First, the geographic dispersal of Amazigh villages and

their being surrounded by Arabic-speaking communities have fostered the use of

Arabic in interaction with the outside world, including commerce and other

transactions. Second, the lack of employment opportunities in the Amazigh

villages forces men to migrate to cities where Arabic is the dominant language,

leaving behind their families. Living in such urban areas influences the status

of AL in the sense that these men end up preferring the use of Arabic in all

circumstances which allow its. Third, the liberation of women in the aftermath

of the independence has given all Amazigh girls access to education in Arabic.

This has resulted in the disappearance of monolingualism among these girls.

Finally, there is a lack of solidarity between Amazigh villages such as between

Douiret and Chenini and between Tamazret and Taoujout despite their

geographical proximity.

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 4

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 5

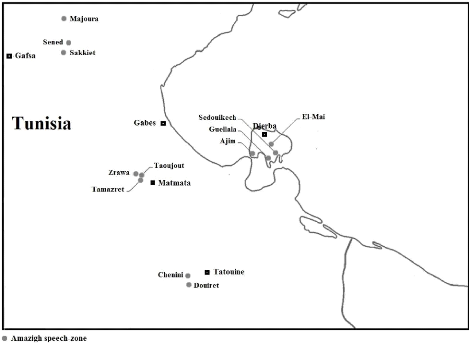

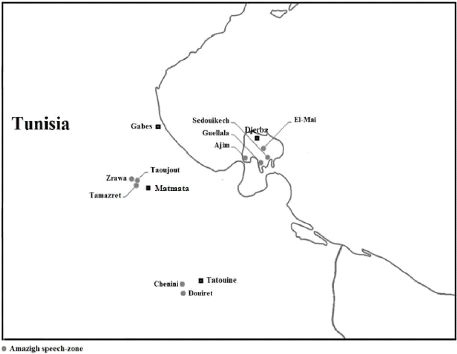

The regression of AL in Tunisia is indicated by the decrease

in the number of Amazigh villages from 12 in 1968 (see Appendix I) to nine in

1983 (see Appendix J). Indeed, Pencheon (1968) identifies 12 villages where

Amazigh is still spoken. Specifically, in Sened, Sakkiet, and Majoura, east of

Gafsa, only the elderly people can speak the language. In contrast, Tamazret,

Taoujout, and Zrawa, west of Matmata, are still entirely Amazighophone.

Moreover, in Djerba only Guellala is still completely Amazighophone whereas one

third of Ajim and less than half of Sedouikech are Amazighophone and some 200

or 300 people in El-Mai seem to speak Amazigh. In Tataouine, Douiret and

Chenini are still entirely Amazighophone. However, Maamouri (1983a, p. 14)

asserts that AL is geographically confined to the villages of Zrawa, Tamazret,

Taoujout, Guellala, Ajim, Sedouikech, El-Mai, Chenini, and Douiret. Maamouri

(1983a, p. 14) also asserts that traces of AL have completely disappeared from

the area of Sened, Majoura, and Sakkiet and reports that AL is occasionally

spoken in Tunis and other big cities by the doughnut vendors (ftayriyya),

central market porters, and newspaper vendors who had come from different

Amazigh villages in search for work. According to a more recent publication

(Gabsi, 2003), the Tunisian areas where AL is still spoken today are: Douiret,

Chenini, Zrawa, Tamazret, and Taoujout, Guellala, Ajim, Sedouikech, and

El-Mai.

As has been just mentioned, Amazigh is still spoken today in

many villages such as Zrawa, the focus of this study. The use of AL in Zrawa

raises interest in investigating what factors have contributed to AL

maintenance. The following section provides details about the village itself

and its inhabitants.

1.2. Context of the Study

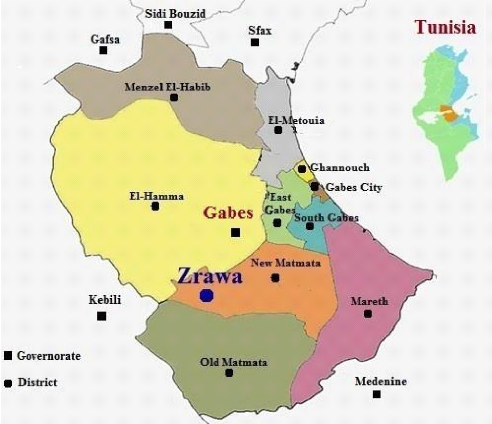

The current study was conducted in the Amazigh village of

Zrawa. This village is officially a part of New Matmata which itself is a

district of Gabes, a governorate in the south-east of Tunisia (see Appendix K).

Zrawa is located approximately 47 kilometers from

Gabes City and 24 kilometers from New Matmata. It is isolated

from the Arabic-speaking neighboring communities. Zrawa is divided into Old

Zrawa and New Zrawa. Old Zrawa is a cluster of abandoned old buildings located

on top of the mountain with a population reduced to one Amazigh family. New

Zrawa, on the other hand, is a small modern village where modern commodities

are available, namely running water, electricity, telephones, and the internet.

According to Said (a pseudonym), a teacher, New Zrawa was created in the 1978.

According to local informants, the road that links Zrawa to New Matmata divides

New Zrawa into two territories. Thus, the one to the north-west of the road is

part of El-Hamma (Gabes) district and is officially called «Farhat

Hachad». The one to the south-east of the road, on the other hand, is part

of New Matmata (Gabes) district and is officially designated

«Zrawa».

Having given some details about the place where the present

research was carried out, it is necessary to provide details about the Amazigh

population in Zrawa. Based on the Municipal Vote Register of May 2016 issued by

the Ministry of Local Affairs, the population of Zrawa has reached 1328

inhabitants. This number does not include Zrawi (adjective from Zrawa) people

who live in «Farhat Hached» and those who have migrated to other

Tunisian regions or abroad. There are no statistics concerning the number of

Zrawi Amazighophones who have migrated to other regions or abroad. Mohamed (a

pseudonym), a member of an Amazigh cultural association, claimed that there are

about 5000 Imazighen residing in Zrawa, with its two parts mentioned earlier,

and thousands of Zrawi Imazighen families and individuals living in Tunis and

abroad.

According to Mohamed and other participants, Imazighen

represent the majority of the population in Zrawa and the remainder of the

inhabitants consists of Arabic-speaking families and individuals from other

regions. Indeed, Mohamed informed me that there were about 50 Arab-speaking

inhabitants made up of families and individuals from Dhiba (the governorate of

Tataouine) and a six-member family from El-Hamma. In the same vein, Arij (a

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 6

pseudonym), a university graduate, told me that the number of

Arabic-speaking families settled in Zrawa exceeds that of Arabic-speaking

individuals. As a consequence, Amazigh is predominantly spoken in Zrawa.

Actually, what is interesting about Zrawa is the impact that the contact

between Amazighophones and Arabophones has on Arabic-speaking children and

adults. Indeed, Arabophone children learn Amazigh in the neighborhoods when

mixing with Amazighophone children. In fact, I witnessed the use of Amazigh by

two Arabic-speaking children from El-Hamma when they were conversing with their

Amazighophone peers. For adults, as three of my informants told me, can speak

Amazigh while others can only understand it. For those who can speak Amazigh

they do not use it. Indeed, Mahdi (a pseudonym) told me that his employee can

speak Amazigh; however, I noticed that they do converse in TA. For those who

can only understand Amazigh they reply in TA whenever addressed in Amazigh.

The Zrawa Amazigh community has some linguistic, economic,

social, and religious characteristics.

· Linguistically speaking, bilingualism, as suggested from

the findings of the present study, is the norm among the Zrawi Imazighen whose

linguistic behavior consists in alternating between AL and TA. Indeed, the

majority of them are sequential bilinguals. Sequential bilingualism refers to

those who acquire one language from birth and a second language later (Baker,

2001). As such, they acquire Amazigh within the family and acquire TA as a

result of schooling, migration, and contact with the media (e.g. watching

Tunisian-Arabic-speaking series on TV), all of which involve contact, whether

direct or indirect, with Arabic-speaking people. Monolingual Zrawi

Amazighophones, on the other hand, consist of those aging women who have had

little or no contact with Arabic-speaking people and of young children who are

not of school age yet. Once they attend school, Amazighophone children follow

the national education curriculum and as a result learn Modern Standard Arabic,

French, and

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 7

English. Arij , a university graduate, informed me that the

majority of teachers at the primary school of Zrawa are Arabophone and only

four among these, including the headmaster, are Zrawi Amazighophones.

Illiteracy in Amazigh is widespread among Imazighen due to the fact that

Amazigh is essentially a spoken language acquired within the Amazigh families.

In fact, among the many Imazighen I communicated with (more than 20

individuals), only three claimed that they can write AL.

· From an economic point of view, Zrawi Imazighen are

famous for being bakers. They own many bakeries not only in Tunisia but also in

France. Indeed, Mohamed informed me that there are 25 bakeries in France owned

by Zarwi Imazighen. He also gave me the example of a Zrawi Amazigh family which

owns five bakeries in Tunis. Some of Zrawi bakers move out of Zrawa without

their families. This is the case of the father of one informant. Other bakers

move out of Zrawa with their families. This is the case of Tarik (a pseudonym),

a Zrawi man who lives in Gabes City and owns a bakery there. As Arij informed

me, because of the lack of job opportunities in Zrawa, young people move to big

cities such as Tunis in search for a better life. She said that there are only

two job opportunities available to Zrawi youth, which themselves are scarce: to

work in bakeries or in construction fields and these opportunities are

themselves scarce.

· Socially speaking, members of the Amazigh population in

Zrawa are inter-related by means of endogamy, by sharing the same economic

activities mentioned earlier, and by being geographically concentrated. Zrawi

Imazighen, especially men, have frequent contact with each other. The typical

places where Amazigh men meet are the street, the cafés, the souk (rural

market), and the mosque.

· As to religious affiliations, Zrawi Imazighen, as Mohamed

asserted, are Maliki Moslems. That is, they are followers of the Maliki school.

It should be mentioned that the Friday sermon (khotbat al-joumou'a) is

delivered in Arabic.

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 8

1.3. Rationale and Objectives of the Study

Factors influencing AL maintenance in Tunisia have not been

addressed by linguists. To my knowledge, there is no research about the factors

contributing to or hindering AL maintenance among the Tunisian Imazighen. As

such, it is important to investigate the factors underlying the current use of

AL in Tunisia by a number of speakers, which is estimated by Ennaji (2005) to

be around 100.000.

One major aim of the present study is to shed light on the

factors contributing to the maintenance of Amazigh in Tunisia. Indeed, this

research focuses on four factors that are said to influence LM and supposed to

be relevant to AL in Tunisia, and particularly in Zrawa: the geographic

concentration of the community, the key role of the families, the positive

language attitudes, and the perceived linkage between language and identity.

With emphasis on the factors contributing to AL maintenance in

Tunisia, the present study seeks to answer the following research questions:

1. To what extent does the geographic concentration of the

Zrawa Amazigh community help maintain AL, if at all?

2. What do Zrawa Amazigh families do to maintain AL, if at

all?

3. What influence do Zrawa Imazighen's attitudes towards AL

have on AL maintenance, if at all?

4. Whether and to what extent does the perceived connection

between language and identity affect AL maintenance?

1.4. Significance of the Study

The study emanates from the researcher's attempt to explore

the factors underlying AL maintenance among a sample of Zrawi Imazighen. It

attempts to present the factors that most contribute to keeping AL alive. The

results of the study are hoped to generate valuable insights which can be of

relevance to Amazigh people in Zrawa and, perhaps, to other

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 9

Amazigh groups elsewhere. Moreover, the study is significant

because it encourages other researchers to investigate AL maintenance in other

Amazigh villages and in cities where Amazigh families and individuals live.

Furthermore, this study is hoped to draw the attention of sociolinguistics and

policy makers to the vulnerable situation of AL in Tunisia, given the fact that

it is a dying language, and encourage them to make decisions in order to

maintain and revitalize this language which is the indigenous language of the

country, and therefore, an important aspect of the national heritage.

1.5. Design of the Study

A mixed methods approach is used in this study in order to

provide an in-depth complete understanding of AL maintenance in Zrawa. This

approach stipulates the use of quantitative and qualitative data collection

methods. In fact, data for the study will be generated by the means of one

quantitative data collection technique, namely a questionnaire, and two

qualitative data collection methods: participant observation and

semi-structured interview. Participant observation will elicit data about the

geographic concentration of Zrawa Amazigh community. As to questionnaires and

semi-structured interviews will be employed to collect data about the way AL is

acquired and used within the Zrawa Amazigh families, the attitudes towards AL

and its maintenance, and the link between AL and Amazigh identity. Thus, the

study will hopefully uncover the underpinnings of AL maintenance in the Zrawa

Amazigh community and provide ground for a discussion of its chances for

survival in the future as a minority language.

1.6. Overview of the Study

The study compromises five main chapters. The first chapter is

devoted to the Introduction. It describes the background, the setting, the

rationale, the design, and the purpose of the study. The second chapter

provides a review of the literature relevant to LM. The third chapter deals

with the methodology followed by the researcher in order to answer the

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 10

research questions. In fact, it provides a detailed

description of the participants, the instruments, data collection and data

analysis procedures. The fourth chapter presents the main findings of the

research and discusses them. Finally, the Conclusion summarizes the major

results of the study, lists its major implications and limitations and provides

some suggestions for future research.

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 11

Chapter Two: Literature Review

2.0. Introduction

This chapter begins with highlighting the importance of

language maintenance. Then, it presents a review of the literature on language

maintenance and the factors contributing to it and those hindering it; hence,

facilitating language shift. Reviewing previous research dealing with these

factors is thought to be helpful in putting this study into perspective and

identifying the related issues.

2.1. The Importance of Language

Maintenance

It seems that definitions of language maintenance (LM)

provided by different scholars (Fishman, 1989; Srivastava, 1989; Mesthrie,

2001; Coulmas, 2005) point to the idea of retaining a particular language

despite the pressures it faces from another language. This implies that LM

occurs in a situation of contact between two groups of people speaking distinct

languages. As Fishman (1964) puts it, «the basic datum of the study of

language maintenance and language shift is that two linguistically

distinguishable populations are in contact and that there are demonstrable

consequences of this contact with respect to habitual language use» (p.

33). Not only are the languages spoken by the two groups distinct but also they

have different status, that is, the language of one group is more powerful than

the language of the other. Thus, the weaker language faces a competition from

the stronger one; however, its speakers hold on to it (Mesthrie, 2001). To

achieve LM, speakers of the weaker language often seek to transmit it from one

generation to another. Assuring inter-generational linguistic continuity is

indicative of LM (Fishman, 1989).

It is worth noting that LM is related to language shift (LS)

defined by Srivastava (1989) as «a shift from the use of one language to

the use of another» (p. 10). As Pauwels (2005, p. 719) points out,

studying LM often involves the identification of the domains and situations in

which the language is no longer used or is gradually regressing.

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 12

The importance of LM has been emphasized by many scholars. For

example, Dorian (1987, p. 64) states that although it is difficult to maintain

a language, there are reasons for undertaking maintenance efforts. Among these

reasons, she mentions three: (a) LM can lead to a reversal of negative

attitudes towards a particular language; (b) LM can contribute to the

transmission of traditions and customs over generations; and (c) LM can be

economically beneficial in the sense that it they provide not only employment

for teachers and translators of these languages but also greater opportunities

for business and international trade. In the same vein, Tamis (1990, p. 499)

points out that learning the mother tongue helps children enhance their

relations with their family members especially their parents. Likewise, Garner

(1988, pp. 42-47) states that enabling children to talk with their elders, most

usually their grandparents, is an important reason for language maintenance for

both Russian and Swedish parents.

2.2. Language Maintenance Research

Language maintenance and language shift as a separate field of

study dates back to the last part of the 19th century. According to

Fishman (1964, p. 32), this field has its origins in the literatures which

continued from the latter part of the 19th century into the Second World War

days, the 1953 Conference of Anthropologists and Linguists, and the work of

Uriel Weinreich and Einar Haugen. The study of LM and LS, as Fishman (1964, pp.

33) points out, is divided into three sub-fields: (a) habitual language use at

more than one point in time or space under conditions of intergroup contact;

(b) antecedent, concurrent or consequent psychological, social and cultural

processes and their relationship to stability or change in habitual language

use; and (c) behavior toward language in the contact setting, including

directed maintenance or shift efforts.

The literature on LM and LS points to a multitude of factors

affecting LM and LS. Some scholars did outline typologies of LM and LS factors.

For example, Giles, Bourhis and

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 13

Rosenthal (1977) proposed the ethnolinguistic vitality

framework which includes 14 factors affecting minority language vitality. These

factors are divided into three types: status, demography, and institutional

support factors. Giles et al. (1977) introduce status factors as «a

configuration of prestige variables of the linguistic group in the intergroup

context» (p. 309). This means that the more status an ethnolinguistic

group has, compared to other groups, the more likely it is to maintain its

language. Status factors are broken down into economic, social,

socio-historical, and language status factors. The demographic factors are

connected to the sheer numbers and geographic distribution of group members.

These factors are broken down into «group distribution factors»

(national territory, group concentration, and group proportion) and «group

number factors» (absolute numbers, birth rate, mixed-marriages,

immigration, and emigration). The institutional support factors refer to

«the degree of formal and informal support a language receives in the

various institutions of a nation, region, or community» (p. 309). That is,

the more support a minority language receives from both governmental and

nongovernmental institutions, the more vitality it has. Giles et al.

(1977) describe the aforementioned factors as being «objective»

and acknowledge that «a group's assessment of its vitality may be as

important as the objective reality» (p. 318). As a consequence, Bourhis,

Giles and Rosenthal (1981) proposed the subjective vitality questionnaire as a

way to assess in-group members' perception of in-group and out-group vitality

on each of the factor included in the «objective» vitality model.

Similarly, Edwards (1992, pp. 49-50) suggests that a minority

language situation can be influenced by 33 factors. He classifies these factors

into 11 categories, namely demography, sociology, linguistics, psychology,

history, politics, geography, education, religion, economics, and the media,

with three factors attributed to each category. For instance, demography

factors include numbers and concentration of speakers, extent of the language,

and rural-urban nature of setting. Likewise, sociology factors have to do with

socioeconomic

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 14

status of speakers, degree and type of language transmission,

and nature of maintenance or revival efforts. Similarly, psychology factors

consist of language attitudes of speakers, aspects of the language-identity

relationship, and attitudes of majority group towards minority group. Edwards

acknowledges that these are not the only factors.

In the Tunisian context, little research has been carried out

on the factors affecting AL maintenance. Maamouri (1983, p. 14) states that the

regression of AL has been due to the development of the educational system and

the spread of mass media. In the same vein, Pencheon (1983) argues that

geographic dispersal, migration to big cities, access to education, and lack of

solidarity between proximate Amazigh villages have all contributed to the

regression of AL. Battenburg (1999) goes as far as to state that AL in Tunisia

is facing gradual death. In his study of AL in Douiret, Gabsi (2003, p. 291)

points out that the sociolinguistic factors leading to AL regression are: a)

the low prestige of AL as a mother tongue; b) the constant migration of

Imazighen from Douiret to other major Tunisian cities; and c) the modernization

of Imazighen's way of life. Moreover, Hamza (2007), in his study of AL in

Douiret, Chenini, Guellala, and Tamazret, states that positive attitudes

towards Arabic have promoted the shift from the use of AL to the use of Arabic.

Such attitudes are indicated by the fact that most of the 100 participants in

the study favored the use of Arabic as an in-group language of communication.

Also, the parents among these participants viewed Arabic as a tool to gain

access to education and a vehicle for social mobility. In addition, Gabsi

(2011) indicates that LS is underway in the villages of Douiret and Chenini.

Based on the situation of AL in these two villages, Gabsi (2011) suggests that

in Tunisia there is no generation of Amazigh monolinguals and that

multilingualism is the norm among the Tunisian AL speakers.

It seems that all these studies have highlighted the decline

of the AL in Tunisia. However, there is no investigation, at least to my

knowledge, on the factors which explain AL

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 15

maintenance in one particular village such as Zrawa, Gabes,

given the fact that this language has disappeared from the villages of Sened,

Majoura, and Sakkiet in the govenorate of Gafsa (Maamouri, 1983). The following

two sections review literature on the most important factors of LM and LS.

2.3. Factors Contributing to LM

This section deals with some of the factors of LM discussed in

the literature on language maintenance and shift.

2.3.1. Geographic concentration of

speakers

The geographic concentration of the speakers of a minority

language affects the maintenance of that language. According to Holmes (2013,

pp. 64-65), living in the same neighborhoods and meeting on a daily basis help

families belonging to a minority group maintain their language. Holmes (2013)

gives the examples of four immigrant communities: the Chinese community in the

United States of America, the Greek community in New Zealand, and the Indian

and Pakistani communities in Britain. To start with, Chinese people who live in

the Chinatown areas of big cities are much more likely to maintain a Chinese

dialect as their mother tongue through to the third generation than those who

move outside the Chinatown area. As to the members of the Greek community in

Wellington, New Zealand, they have established shops where imported foodstuffs

from Greece are sold and where they speak Greek to each other. Likewise,

Pakistani and Indian communities living in British cities have established

their own shops where Pakistanis use Panjabi, and Indians use Gujerati, with

each other.

As argued by Giles et al. (1977, p. 313), the

concentration of a minority ethno-linguistic group in a given area (territory,

region, or country) contributes to the maintenance of its language in the sense

that its members have the opportunity to use that language as a means of daily

communication. They mentioned the example of Canada where French Canadian

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 16

families living in isolated areas outside Québec and

being in contact with English Canadians have lost their French language within

few generations.

Many studies have shown the role of geographic concentration

in LM. Laleko (2013, p.95), who investigated the vitality of Russian as a

heritage language in the United states, found that it was somewhat easy for

Russian immigrants living in large cities and metropolitan areas to maintain

ties with their heritage language and culture due to the existence of the

relevant infrastructure, including small businesses that cater to the Russian-

speaking population, most remarkably food stores and restaurants, bookstores,

art galleries, hair and beauty salons, medical offices, various real estate and

insurance agencies, and religious organizations. In his study of LS among

Chinese-Americans, Li (1982, pp. 118-

119) indicates that residing in Chinatown assists in resisting

LS; however, Chinese- Americans, especially school children, residing outside

Chinatown will usually adopt English as their mother tongue. In the same vein,

Al-Khatib and Al-Ali (2010) reviewed previous research on the maintenance of

minorities languages among the five minority groups residing Jordan (Kurds,

Armenians, Gypsies, Chenchens, and Circassians). They observe that the Gypsies,

Chechens, and Circassians have maintained their ethnic languages and cultures

thanks to their residence in co-ethnic neighbors within close-knit communities,

with limited contact with the majority language and culture; however, the

Armenians and the Kurds have shifted towards the dominant language and culture

because of being dispersed across the large urban centers. 2.3.2.

Family

The family can play a key role in LM. As Fishman (1991) points

out, the family «has a natural boundary that serves as a bulwark against

outside pressures, customs and influences. Its association with intimacy and

privacy gives it both a psychological and a sociological strength that makes it

peculiarly resistant to outside competition and substitution» (p. 94).

In

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 17

the same vein, Brown (2008) states that the home or family is

«the last bastion in terms of language maintenance» (p.1). Results

from Renz's (1987) survey of respondents of Portuguese origin in California

indicate that family was ranked as the most important factor in linguistic and

cultural maintenance.

Parents, in particular, play a key role in LM. Lieberson and

Curry (1971, p. 146) indicate that what language parents choose to speak to

their children affects, to a large extent, LM or LS. Parents play a crucial

role in transmitting the mother tongue either by teaching it to their children

(Okamura-Richard, 1985, p. 63; Sridhar, 1988, p. 84) or by speaking it at home

(Sridhar, 1988, p. 84).

Many studies confirm the role of parents in LM. Nesturik

(2010), in her investigation into LM among 50 Eastern European immigrant

parents living in the USA, found that the majority of the participants in the

study communicated with their children in their native language at home in

order to maintain it. Al-Sahafi (2015) also investigated the role of ten Arab

parents in the maintenance of Arabic in New Zealand. The findings reveal that

the participants were determined to maintain and transmit the Arabic language

to their children. In a similar vein, Gomaa (2011) examined the efforts of five

Egyptian families living in Durham, United Kingdom, to transmit Egyptian Arabic

to their children. The results show that, as a strategy to maintain Egyptian

Arabic, the parents insisted that their children speak it at home. For example,

when their children spoke to them in English, the parents replied in Egyptian

Arabic and told them to speak Egyptian Arabic as long as they were at home. In

her study of a Turkish family living in Western Pennsylvania, United States of

America, Tatar (2015) found that the parents had tried their best to teach

Turkish to their children, including speaking it with them most of the time.

Likewise, Becker (2013) studied three Korean immigrant families living in West

Michigan, USA. The findings reveal that parents in the three families

encouraged their children to use Korean at home and wanted them to achieve

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 18

high proficiency level in Korean. Moreover, Abdelhadi (2017)

in his study of LM among the Arabic-speaking community in Toowoomba, Australia,

found that parents implemented many teaching strategies, such as translation,

teaching writing, and reading stories, in order to maintain the Arabic language

and transmit it to their children.

2.3.3. Language attitudes of speakers

Language attitudes are defined by Myers-Scotton (2006) as

«subjective evaluations of both language varieties and their speakers,

whether the attitudes are held by individuals or by groups» (p. 120).

Reviewing the literature on language attitudes, Giles, Hewstone, and Ball

(1983) indicate that the term includes:

Language evaluation (how favorably a variety is viewed),

language preference (e.g., which of two languages or varieties is preferred for

certain purposes in certain situations), desirability and reasons for learning

a particular language, evaluation of social groups who use a particular

variety, self-reports concerning language use, desirability of bilingualism and

bilingual education, and opinions concerning shifting or maintaining language

policies. (p.83)

Language attitudes can be studied in different ways. Indeed,

O'Rourke (2011, pp. 24-26) mentions three approaches to the study of language

attitudes: the societal treatment of language, the indirect assessment within

the speaker evaluation model, and the direct measurement with interviews or

questionnaires. The social treatment of language includes techniques such as

content analysis, observational analysis, participant observation, and

ethnographic study of language choices. These techniques do not involve

directly asking respondents about their attitudes. As to the indirect

assessment of language attitudes, it involves the use of the matched-guise

technique whereby listeners are asked to rate tape- recorded voices spoken by

the same speaker but in different languages on a number of personal traits such

as sociability, leadership, ambition, and sense of humor. This technique

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 19

aims at eliciting the listeners' attitudes towards the

different voices on the basis of their attitudes towards the different

languages. Finally, the direct assessment of language attitudes is done through

questionnaires and interviews addressing particular aspects of language.

Particularly speaking, positive language attitudes towards a

minority language can contribute to its maintenance. These attitudes, according

to Holmes (2013), include associating the minority language with high value and

regarding it with pride. Holmes (2013) believes that such attitudes assist with

the efforts to use the language in a diversity of domains so that people can

restrain the pressure from the majority group to adopt their language. In the

same vein, Bradley (2002) states that «perhaps the crucial factor in LM is

the attitudes of the speech community concerning their language» (p.

1).

Many researchers have addressed attitudes towards heritage

languages. For example, the findings from Becker's (2013) study suggest that

the participants believed that maintaining Korean was critical for their

children's Korean identity formation and for family communication. In Tatar's

(2015) study, the parents of the immigrant Turkish family living in Western

Pennsylvania show positive attitudes towards learning and speaking Turkish as

their HL at home and express a strong desire for their children to learn

Turkish. Indeed, the father believed that it was essential for his children to

learn Turkish because it is their heritage language and because they need it in

their communication with the members of the family in Turkey and of the Turkish

immigrant community in the US. As for the mother, she stated that learning

Turkish as an additional language would have a positive impact on children's

brains. As to the children, they believe that Turkish is part of their identity

and a means of communication with Turkish relatives in Turkey. Furthermore, the

results from Gomaa's (2011) study (see section 2.3.2) indicate that

parents believed that it was very important for them to transmit Egyptian

Arabic to their children for two reasons. First, they considered Egyptian

Arabic to be a means to passing on their Egyptian culture and traditions.

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 20

Hence maintain the children's Egyptian identity. Second, they

believed that speaking Egyptian Arabic would allow their children to

communicate with their grandparents and extended family living in Egypt.

2.3.4. Aspects of the language-identity

relationship

It seems that there is a link between language and ethnic

identity which Phinney (2003) defines as «a dynamic, multidimensional

construct that refers to one's identity or sense of self as a member of an

ethnic group» (p. 63). Indeed, ethnic-group membership is often based on

which language one speaks (Trudgill, 2000; Padilla & Borsato, 2010). For

example, Trudgill (2000, p. 54) gives two cases in which ethnic-group

membership is defined by language. The first case is found in one suburb in

Accra in Ghana where there are more than eighty languages the native speakers

of which often identify themselves as being members of a tribe or group on the

basis of which these languages is their mother tongue despite the fact that

most of them are bi- or tri-lingual. The second case is found in Canada where

the two ethnic groups, namely English Canadians and French Canadians, are

defined mainly by whether their mother tongue is English or French. In

addition, using the language of one's ethnic group can serve as an indication

of the involvement in the social life and cultural practices of that group

(Phinney, 1990, p. 505). Moreover, language can be viewed as an essential

component of ethnic identity. Actually, socialization, the process by which a

child acquires appropriate behavioral alternatives, takes place through the

language used within the family and the community, which makes language an

essential constituent of ethnic identity (Padilla & Borsato, 2010, pp.

11-12). Furthermore, language can be a marker of one's ethnic group (Mesthrie

& Tabouret-Keller 2001; Kotzé, 2001; Ennaji, 2012). Viewing language

as a marker of ethnic identity can contribute to its maintenance. As Holmes

(2013, p. 64) argues, a minority language is likely to be maintained longer in

areas where it is considered as an important symbol of ethnic identity. This is

the case of Polish and Greek people immigrants

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 21

in many countries regarded their languages as a primary

condition for preserving their identity. Consequently, they have maintained

their languages for three to four generations. The same is true for Greek

immigrants in USA, Australia, and New Zealand. In the same vein, O'Rourke

(2011) states that «the strength of a minority language can be predicted

by the degree to which speakers value their language as a symbol of group or

ethnic identity» (p. 19).

The close relationship between language and ethnic identity is

confirmed by results from several studies. Hatoss (2005) studied LM among 50

families in the Hungarian community of Brisbane, Australia, using

questionnaires and telephone interviews. The sample for the study was made up

of 50 families. The findings suggest that most of the participants (93%)

demonstrated a strong attachment to Hungarian and regarded it as an important

tool for maintaining their identity. Additionally, Chiung (2001) investigated

the relationship between mother tongue and ethnic identity among 244 Taiwanese

students in Taiwan. These students were speakers of different native Taiwanese

languages. Since Mandarin Chinese was the official language of Taiwan for more

than 50 years, there was a decline in the use of Taiwanese native languages.

The Results indicate that the maintenance of one's ethnic language is a

contributing factor to the maintenance of one's ethnic identity while the

erosion of one's ethnic language does not necessarily result in the erosion of

one's ethnic identity.

However, findings from other studies indicate that there is no

tight linkage between language and ethnic identity. For example, Ahn (2008)

studied ethnic identity and language use among 20 United States-born Koreans

living in Hawaii. The results show that none of the participants identified

themselves as Americans even though English was their first language. In

addition, Kang (2004) investigated the relationship between heritage language

maintenance and ethnic identity among 18 Korean and Chinese immigrant college

students (eight Chinese and ten Korean) in New Jersey, the United States. The

findings from the study

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 22

reveal that the Chinese and Korean participants did not

consider their heritage languages to be markers of their ethnic identities.

Moreover, Bentahila and Davies (1992) in their study of LS in Morocco conclude

that there is an unnecessary relationship between language and ethnic

identity.

2.3.5. Government policy

Government policies in favor of a minority language can

contribute to its maintenance. The following are examples of maintenance

efforts undertaken by governments in three different countries: Morocco,

Australia, and New Zealand. To start with, Sadiqi (2010, p. 35) emphasizes the

support that AL receives from the Moroccan government. In fact, she states that

the establishment of the Royal Institute for Amazigh Culure (Institue Royale

pour la Culture Amazighe en Maroc) in 2001 in Rabat marked the beginning of the

process of the institutionalization of AL. She also states that AL has been

included in Morocco's public school curriculum as a result of an agreement

signed between the Institute and the Ministry of Education in 2003. In the

Australian context, Wurm (1974, p. 217) mentions that the Australian government

established the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies in Canberra in 1961

for the purpose of promoting research on aspects of aboriginal culture in the

widest sense. He adds that the main interest of the institute has been in

linguistics, which has resulted in the rediscovery of many languages and in

government's positive attitudes towards and greater interest in aboriginal

languages. As to the New Zealand context, Caldas (2013, p. 361) emphasizes the

efforts of the New Zealand government to maintain the indigenous Maori

language. Such endeavors include funding the establishment of the Maori

Language Commission (1987), Maori radio stations, and the Maori Television

Service (2003), the compilation of a Maori dictionary, the development of Maori

school immersion and bilingual programs, and the tuition to attend university

courses offered in Maori. All these efforts aimed at promoting community and,

especially, family use of Maori. Indeed,

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 23

many Maori reported learning the language from taking classes,

watching TV, or listening to radio.

2.3.6. Education

The influence of education on LM is clearly evidenced in the

literature on the topic. Li (1982, p. 11) points out that there is often a

connection between parents' educational level and LM in the sense that educated

parents would be more aware of maintaining the mother tongue. Similarly, Clyne

(1988, p. 31) indicates that parents who are educated may contribute to LM by

devoting time and efforts to the maintenance of their minority group's heritage

and culture. According to Dorian (1987, p. 65), Irish Gaelic has been

maintained because it is accepted as a legitimate language of study in Ireland,

whereas in Scotland the status of Gaelic has been eroded because it is

generally not available as a school subject option. He states that:

Irish school children ... are most unlikely to be denied the

opportunity to study Irish if

they wish it; over most of Highland Scotland, school children

and their parents are still

told either that there are no teachers available to teach

Gaelic or that there is no room in

the curriculum for the subject. (p. 65)

A related point, in her study of Greek in Australia, Tamis

(1990) points out that including Greek in the educational system leads to a

corresponding increase in its social value and/or acceptability. She states

that:

The introduction of MG (mother tongue Greek) as an examinable

subject for tertiary entrance requirements in 1973 and its teaching in certain

Australian Universities and Colleges of Education ... further increased not

only the functional value of the mother tongue, but also stipulated the

acceptability of MG in the Greek community. (p.498)

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 24

2.3.7. Religion

Religion may be an important factor affecting LM. Actually,

church services and activities are often, or can be, conducted in the mother

tongue of a minority group. For example, in his study of Greek-Australians,

Smolicz (1985, p. 26) indicates that Greek is used in the Greek Orthodox Church

in Australia. In the same vein, Sridhar (1988, p. 80) points out the importance

of religion for LM through ritual and prayer. Putz (1991), in his study of a

German Australian speech community, indicates that "membership of a religious

denomination ... seems to promote language maintenance which, in turn,

underlines the importance of a combination of domains, i.e. religion, ethnicity

and language" (p. 487).

It appears that Smolicz (1985), Sridhar (1988), and Putz

(1991) share the view that religion contributes to LM. Such view is different

from that of Fishman (1972). Indeed, Fishman (1972) suggests that religion

substitutes for and preserves ethnicity but it is not sufficient for LM. He

also suggests that the function of language in the church is primarily to

safeguard the faith of the people in an urban situation, and therefore, the use

of the vernacular in the mass is not sufficient for LM.

In the case of AL, religion has caused a negative impact on

the maintenance of this language. In fact, the close relationship between

Arabic and Islam has facilitated the dominance of Arabic over AL (Ennaji, 2005,

p. 10). Besides, the spread of Arabic throughout North Africa has been due the

necessity of using Arabic in praying (Sadiqi, 1997, p. 9). Furthermore, one

should be literate in Arabic in order to understand the Quran (Ennaji, 20025,

p. 10). In a nutshell, Arabic is viewed as the language of Islam.

2.3.8. Media

The media can be a key domain in LM. Putz (1991, p. 484)

points out that German television in Australia promotes interest in

contemporary German culture and language, resulting in an increase in the use

of the mother tongue, with specific reference to the younger

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 25

generation. Resnick (1988, p. 93) states that it is common for

immigrant groups to broadcast or publish in their language. Government support

for the media could also assist in language and culture maintenance. An example

of such support is highlighted in Cartwright's (1987) study of the Anglophone

minority in Quebec, where book publishing, theatrical, radio and television

production, and regional newspapers and magazines have received government

support.

2.3.9. Socio-cultural organizations

Socio-cultural organizations, including clubs and

associations, may contribute to LM. Clyne (1988) and Putz (1991), in their

studies of LM among German-Australian communities, conclude that not only do

social clubs increase LM, but also they are, in the words of Putz (1991), "one

of the most important domains promoting language maintenance in ethnic

communities" (p.487). Fishman (1972, p. 49) stated that the role of cultural

organizations in LM is more important than the press or broadcasting. Indeed,

McCarty (2012, p. 561) indicates that such American organizations as the

Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival, the American Indian

Language Development Institute, the Indigenous Language Institute, the National

Alliance to Save Native Languages, and the Stabilizing Indigenous Languages

Symposium played a major role in the development and passage of the 1990/1992

Native American Languages Act (NALA) which stipulates that it is the federal

government's responsibility to promote the rights of indigenous Americans,

including the use of their languages is schools. In 2006, NALA was reinforced

by the Esther Martinez Native American Languages Preservation Act which

provides financial support to language nest preschools, native language

survival schools, teacher preparation, and materials development.

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 26

2.3.10. Urban-rural nature of setting

The degree of LM can be higher in rurally isolated communities

in contrast to urban communities where people are in contact with other

languages. Thompson (1974, p. 10) points out that urbanization leads to

language shift. Indeed, in his study of the 1970 census in the United States of

America, Thompson (1974, p. 14) identifies two important trends regarding the

childhood residence of Mexicans: The predominant use of Spanish was evident

among the first generation, who came from a rural background (or childhood)

while the use of Spanish decreased in the second and third generations, as the

number of people from a rural background or childhood decreased. Note here that

the shift from Spanish to English was related to the shift from rural areas to

urban areas. Likewise, in her study of language maintenance and contraction

among two groups of Tashelhit (a variety of AL) speakers in southern Morocco,

Hoffman (2006, p. 150) reports that the Native Tashelhit-speaking men who have

migrated with their wives and children to the towns in the 1970s have become

bilingual in Arabic, and their children grow up as Arabic-dominant speakers;

many of them even go so far as to reject their ethnic identity. In the same

vein, Srivistava (1989) points out that an agrarian and rural society would be

more supportive of the minority language than an industrialized and urban

society where the co-existence of a number of speech communities results

«in a state of constant competition and conflict in learning each other's

language» (p. 15). Similarly, Sadiqi (1997, p. 15) in her study of AL in

Morocco indicates that AL regression in rural areas is slower than in the urban

areas because no language competes with it in those areas. In a similar vein,

Holmes (2013, p. 66) believes that «resistance to language shift tends to

be last longer in rural than in urban areas» (p. 66). She cites the

example of Ukrainians in Canada. Indeed, Ukranian has been maintained better

among those living on farms than those living in cities. Also, in New Zealand,

Maori is still used as a language of daily communication in rural areas where

most of the inhabitants are Maori.

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 27

The aforementioned view is different from that held by Fishman

(1964). Indeed, he argues that LM efforts are greatest in the city. He states

that:

Language revival movements, language loyalty movements, and

organized language maintenance efforts have commonly originated and had their

greatest impact in the cities. Intelligentsia and middle class elements, both

of which are almost exclusively urban, have frequently been the prime movers of

language maintenance in those societies which possess both rural and urban

populations. (p. 53)

I have so far dealt with some of the factors contributing to

minority LM. In the next section, I will focus on factors promoting LS.

2.4. Factors Facilitating LS

A number of factors contributing to LS are revealed in the

literature: family, social factors, economic factors, government policy, and

media. These factors will be discussed below.

2.4.1. Family

We have seen in section 2.3.2 that the family is a

factor which strongly promotes LM. Nevertheless, it could cause LS. Parents in

particular may facilitate LS. In fact, in her study of Welsh, Lewis (1975)

points out that "the relation of the child's language to that of the family is

naturally determined to a considerable extent by expressed or revealed

competence of the parents" (p. 107). She also indicates that, in certain

instances, where both parents are bilingual, there is a high degree of English

monolingualism among the children. Moreover, the results from Bentahila and

Davies' (1992) study reveal that some Amazigh Moroccan parents encouraged their

children to use Arabic rather than Amazigh because the latter would not help

them earn their «daily bread». Similarly, in her study of Spanish

maintenance and linguistic shift towards English among Chicano adolescents in

two speech communities in Austin, Texas, USA, Galindo (1991, p. 113) found that

a crucial factor in the shift from Spanich to English was parents' decision not

to teach Spanish to their children. This had to

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 28

do with parents' negative school experiences. Indeed, parents,

including Galindo's, still remembered when they were punished for speaking

Spanish school and made to feel inferior. Thus, these parents did want their

children to be discriminated against because of their language and culture.

In addition to parents, older siblings may also influence the

degree of LS among the young. In other words, when the older siblings use their

mother tongue, which has been influenced by the majority language, to

communicate with the younger siblings, they facilitate LS. Indeed, Sridhar

(1988) states that «the presence of older siblings whose language is

increasingly affected by the mainstream language may make the younger child's

control over the ethnic tongue less secure» (p. 81).

Another way in which the family can promote LS is through

intermarriages. Demos (1988, p. 170) points out that intermarriage causes a

decline in the use of the mother tongue. Furthermore, Paulston (1987, p. 35)

indicates that in cases of intermarriage, there is a shift of one partner to

the language of the more socio-economically favorable group. In the same vein,

Giles et al. (1977, p. 314) suggest that the increase in the rate of

mixed-marriages may lead to LS in the sense that the more prestigious variety

is more likely to be used at home, including the interaction with children.

Moreover, Holmes (2013, p.62) argues that intermarriages can accelerate LS in

contexts where monolingualism is the norm. A typical example of this is the

German community in Australia. Indeed, in intermarriage between a

German-speaking man and an English-speaking woman, English is often used at

home and to children. Also, in the Cherokee community in Oklahoma, USA, when a

Cherokee-speaking person marries outside the community, the children grow up to

be monolingual in English.

2.4.2. Prestige

The shift towards another language may be due to the prestige

or social value associated with that language. That is, people choose a

language due to the social value associated with

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 29

it. Mougeon, Beniak, and Valois (1985) state that «the

language being shifted to enjoys wider currency and greater prestige» (p.

455). In her study of language attitudes in Barcelona, Woolard (1984) indicates

that the shift from Castilian to Catalan is due to the fact that the latter is

more prestigious than the former. Tamis (1990) points out that «the

acquisition and learning of MG (mother tongue Greek) is further inhibited or

promoted by the attitudes of the overall society and the prestige that it

carries amongst teachers and educators" (p. 498).

2.4.3. Length of residence

Language shift can be the result of the length of residence in

an area where a language other than the mother tongue is spoken. In his study

of Japanese in the USA, Okamura- Bichard (1985, pp. 82-83) indicates that the

length of residence can lead to language shift in the sense that regression in

the mother tongue is related to the period of time spent outside Japan. Huls

and van de Mond (1992), in their study of two Turkish families living in the

Netherlands, conclude that the more the length of residence is, the more is the

shift from Turkish to Dutch. 2.4.4. Access

Access can be a factor of LS. As Cartwright (1987, p. 204)

states, the main reason behind learning the language of the dominant society is

that it provides access to certain areas, important in everyday life such as

residence, employment, and daily shopping. In a similar vein, Srivastava (1989,

p. 22) points out that immigrants, in the USA, switch to English because it is

English which determines access to goods and services.

2.4.5. Employment

Employment can play a major role in LS in the sense that

people should be able to speak the language of the working environment in order

to be employed, especially in the more skilled areas of employment. This factor

has been widely-studied in the literature. A general pattern amongst linguistic

minorities is the use of the mother tongue at home and the use of

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 30

the dominant language in the working environment. The results

from Gynan's (1985) study of Spanish in the USA, for example, reveal that

Spanish (the mother tongue) is spoken at home while English (the language of

the host society) is spoken in the working environment. In the same way,

Paulston (1987, p. 53) points out that immigrants may have to learn a language

for purposes of employment and this has proven to be a major cause of LS.

The importance of speaking the language of the working

environment in order to be employed, and the subsequent language shift which

occurs, is discussed in detail by Lieberson and Curry (1971, pp. 131-133). This

study emphasizes the fact that immigrants, in the USA, who are not able to

speak English are "handicapped" (p. 132) and could even be discriminated

against if they are unable to speak English. This research suggests that the

language shift due to employment could also «influence the possibility of

mother tongue shift between the generations» (p.133). In addition,

Cartwright (1987), in his study of language usage in Quebec, points out that in

the working environment the younger Francophones use English more often (as

opposed to French) in comparison to the older respondents. It can, therefore,

be seen that occupation promotes the use of language of the host community.

Furthermore, Schlieben-Lange (1977) and Eckert (1980) in their

studies of Occitan in France indicate that most of the younger members of the

Occitan community are monolingual French speakers. Eckert, for example, states

that «the adult population of the community is consciously transitional -

they have encouraged their children to leave the region to find work, and in

preparation for this they have raised them as monolingual French speakers»

(p. 1059).

Putz (1991, p. 486) summarizes the facts mentioned above in

his study of German in Australia. He indicates that the fact that work

environment is a meeting place of people from various backgrounds necessitates

the need for a lingua franca, which facilitates LS. He said that:

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 31

The work domain seems to be a rather negative factor in the

promotion of language maintenance; the multi-ethnic situation at the work-place

and the prevalence of people from different language backgrounds creates a need

for a lingua franca, i.e. English, in order to facilitate communication among

workers. (p.486)

2.4.6. Migration

The pattern of LS can be accelerated by moving either to

another area of the same country or to another country in search of better

living conditions. Giles et al. (1977) state that «migrants who move in an

area where linguistic groups are in overt or covert competition appear to be

willing (for obvious economic reasons) to adopt the language and culture of the

dominant rather than that of the subordinate linguistic group» (p. 314).

According to Giles et al (1977, p. 315), this has been the case of Welsh

speaking families who had moved at the turn of the nineteenth century to

England or to the English-dominated and industrially- developed areas of south

Wales in order to find jobs. These families had lost the Welsh language within

less than two generations. Pencheon (1983, p. 31) highlights the role of

migration from villages to cities in the regression of AL in Tunisia.

Similarly, Ennaji (1997; 2005) points out that the regression of AL in Morocco

was due in part to the migration of Moroccan Amazighophones from rural villages

to urban areas. Likewise, Hoffman (2006, p.

150) reports that Moroccan native speakers of Amazigh who have

migrated permanently to cities have shifted towards Moroccan Arabic.

2.4.7. Government policy

Government policy towards minority groups and their languages

can promote LM (see section 2.3.5). But, it can also facilitate LS.

Miyawaki (1992, pp. 358-363), in his study of Ainu, Okinawan, and Korean

linguistic minorities in Japan, indicates the unfavorable official attitudes

towards these communities. To begin with, the Ainu population numbers about

25.000, but only ten people are able to speak the Ainu language fluently and

these are over 70

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 32

years old. The decline of the Ainu language was due to the

assimilative language policy of the Japanese government. An example of such

policy is the prohibition to teach Ainu language at school to Ainu children.

Like the Ainu language, the Okinawan dialect has declined as a result of the

government's assimilation policies such as the penalization of the Okinawan

children who speak their language at school. Such decline was manifested in the

fact that only Okinawan people over 50 years old can speak their dialect. The

situation of the Korean language is not so different from that of the Ainu and

Okinawan languages. The Japanese government assimilated 80% of the 642 Korean

schools, established during the Korean War (1950-1953) to the regular Japanese

schools and caused many others to collapse, which had a destructive effect on

the maintenance of the Korean language.

2.4.8. Media

We have seen in section 2.3.8 that the media can

greatly promote LM. Nevertheless, it can contribute to the process of LS.

Maamouri (1983, p. 14) points out that AL regression in Tunisia is due in part

to the general spread of mass media. Young (1988, p. 325) indicates that the

media can contribute to the process of LS especially when there is government

support for the use of a particular language in the media such as television.

In their study of language shift in Morocco, Bentahila and Davies (1992, p.

198) state that the mass media especially television, is one of the factors

contributing to the regression of the AL in Morocco.

2.4.9. Education

As we have seen in section 2.3.6, education can

contribute to LM. However, access to education can lead to LS. Pencheon (198,

p. 31) suggests that the access of Amazigh girls to education in the aftermath

of the independence had contributed to the regression of AL in Tunisia in the

sense that it had led to the disappearance of monolingualism among Amazigh

females. In the same vein, Maamouri (1983a) stated that the rapid development

of the

HERITAGE LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AMONG THE BERBERS 33

educational system in Tunisia had contributed to the

regression of AL. Clyne (1988, p. 31) points out that the lack of education or

lower education leads to isolation from the dominant host community and hence

language maintenance. This implies that education facilitates LS. Ennaji (1997,

p. 29) indicates that the access of Amazigh-speaking children to free education

since Moroccan independence had fostered the regression of AL in Morocco.

2.5. Conclusion

This chapter started with showing the importance of LM.

Besides, it provided a description of two models of LM and LS factors, which

places the study within the research on LM and LS in general, and cited five

publications which had shed some light on the situation of AL in Tunisia. Then,

ten factors of LM were referred to, namely geographic concentration of

speakers, family, language attitudes of speakers, aspects of the language-

identity relationship, government policy, education, religion, the media,

socio-cultural organizations, and urban-rural nature of setting. Some of the

factors contributing to LS were also dealt with. These consisted of family,