|

Influence of an ERP system on the value chain process of multinational enterprises (mnes)( Télécharger le fichier original )par Bosombo Folo Ralph University of Johannesburg - Master in business administration (MBA) 2007 |

Information Management

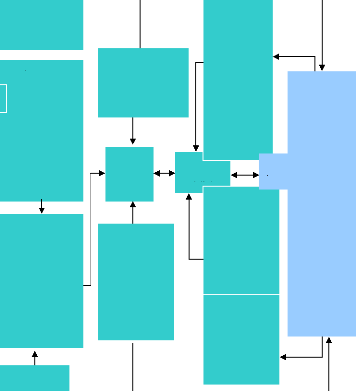

35 Sutton (in Walters & Lancaster, 2000:162-3) proposes the market mechanism as a means to coordinate activities. It is suggested that the term "market co-ordination" be used for the situation in which specialisation is separate and where the value chain comprises a series of sequential individual activities under individual ownership. An alternative model is one in which more than one organisation"... seeks to combine two or more stages under single control and rely upon internal management to ensure co-ordination". Sutton uses the conventional term "vertical integration" for this structure. An organisation may also act as a contractor to co-ordinate the other links in the value chain but relies on external agreements rather than internal management. The vertical co-ordination comprises individual organisations having specific objectives but shared purpose (customer satisfaction) within the value chain. According to Sutton (in Walters & Lancaster, 2000:162-3), vertical integration has alternative structural options, namely breadth and depth. Breadth occurs in companies that rely on co-ordination of some activities while assuming ownership of others. Sutton (in Walters & Lancaster, 2000:162-3) suggests differentiation as breadth being the extent of co-ordination with vertical integration and depth the activities that are combined into one activity, given that the value chain is concerned with value maximisation and cost optimisation. Therefore, the availability of economies of scale and scope is important. These relate to the ability to specialise and gain cost advantages and/or to offer a limited range of specialist products and/or services that have significant impact on customer costs, for which much of the fixed costs are shared. 2.7.5 Value nets A traditional supply chain is designed to meet customer demand with a fixed product line, relatively undifferentiated, one-size-fits-all output and average service for average customers. In contrast a value net forms itself around its customers, who are at the centre. It captures their real choices in real time and transmits them digitally to other net participants. 36 Table 2.1: Key business design differences Old supply chain New value net

Firm Infrastructure

Human Resource Management

Technology Development

Procurement

Real-time integrated scheduling, shipping, warehouse management, demand management and planning, and advanced planning and scheduling across the company and its suppliers Inbound Logistics Web-distributed supply chain management Integrated information exchange, scheduling, and decision making in in-house plants, contract assemblers and components suppliers Real-time availableto-promise and capable-to-promise information available to the salesforce and channels Operations Real-time transaction of orders whether initiated by an end consumer, a salesperson, or a channel partner Automate customer-specific agreements and contract terms Customer and channel access to product development and delivery status Collaborative integration with customer forecasting systems Integrated channel management including information exchange, warranty claims, and contract management Outbound Logistics Real-time inside and outside access to customer information, product catalogs, dynamic pricing, inventory availability, online submission of quotes, and order entry Online sales channels including Web sites and marketplaces Online product configurators Customer-tailored marketing via customer profiling Push advertising Tailored online access Real-time customer feed-back through Web surveys, opt-in/- out marketing, and promotion response tracking Marketing and sales Customer self-service via Web sites and intelligent service request processing including updates to billing and shipping profiles Real-time field service access to customer account review, schematic review, parts availability and ordering, work-order Update, and service parts manage- ment Online support of customer service representative Through e-mail response management, billing integration, co-browse, chat, " call me now," voice-over IP, and uses of video streaming After-Sales Service

For effective value chain reconfiguration, the process of reconfiguring is necessary to an organisation's survival in a changing environment (Normann & Ramirez, 1998:99). Thus, having an offering code that enhances fit for potential value-creating activities between supplier and customer is necessary. This is where the concept of leverage comes in. According to Normann and Ramirez (1998:59), leverage explores

and exploits opportunities based 39 enabling the customer. Both concepts concern the configuration of activities as they are manifested in the relationship linking customer and supplier; that is, in the offering. 2.8 ERP system and e-business: An evolving relationship for value chain extension In the 1990s, software developers developed ERP software, a fuller "suite" of applications capable of linking all internal transactions. Since then the use of ERP software has exploded, and some advocates claim that it is the ultimate solution to information management. While traditional production management information systems have focused on the movement of information within an organisation, Web-based technology facilitates movement of information from business to business (B2B) and from business to consumer (B2C), as well as from consumer to business (Balls et al., 2000:2-3). According to Balls et al., (2000:2-3), research groups such as Forrester, Gartner and AMR all project incredible growth for e-business in the first five years of the new century. Some analysts in Balls et al., (2000:2-6) comment that in their rush to become an e-business, most organisations have decided against implementing an ERP system. Balls et al., (2000: 4-6) have discovered that some client companies are building e-business applications while largely ignoring ERP development, hoping someone, someday will integrate the back end. As a result, companies whose e-business applications have no order-fulfilment and order-status capabilities either lack data or need to recreate it. E-business simply does not work without clean internal processes and data. The choice, though, is not between developing e-business solutions or implementing ERP. Clearly, both are necessary. According to Balls et al., (2000:4-6), making ERP work most effectively in an e-business environment means shedding old notions of ERP. One such notion is whether ERP will always look the same. Balls et al., (2000:2-3) assert that ERP software in the next few years will certainly not look like ERP software designed in the 1990s. The delivery of ERP functionality will also change. For instance, a software vendor that today focuses on one front-end e-business application may in the future build into its products a transaction engine component that can then be attached to other organisations' front-ends. The other option is that ERP vendors will successfully make products more flexible and less difficult to implement, and they will either add e-business functionality or make their systems more compatible with third-party front-end e-business products. Why is this a 40 challenge for ERP vendors? Organisations use ERP software to enable processes that confer a competitive edge. Consequently, e-business is forcing ERP vendors to rethink their products' role within the enterprise. All are in some way looking to broaden ERP functionality to incorporate front-end technology and create trading communities through portals and joint ventures with Web-based technology and other vendors. For many organisations, ERP itself may be delivered over the Web through business application outsourcing undertaken by application service providers. In the future, it is clear that companies will work together in extended value chains. Those that are able to plug their internal IS into the information chain that parallels the physical goods value chain will prosper; those that are not will fail. Successful organisations will be part of a networked team of business partners dedicated to delivering customer value. Very few (if any) organisations will be able to compete single-handedly against such a team. The technology to "team" is available today, and strong teams are already beginning to form. In short, together, e-business technologies (the Internet, the Web, a host of e-enabling technologies) and ERP systems will provide companies with new options for raising profitability and creating substantial competitive advantage (Balls et al., 2000:7). Balls et al., (2000:7) realise that properly implementing e-business and ERP technologies in harmony truly creates a situation where synergism is created. Web-based technology puts life and breath into ERP technology that is large, technologically cumbersome and does not always easily reveal its value. While ERP organises information within the organisation, e-business disseminates that information far and wide. ERP and e-business technologies supercharge each other. The purpose of these new technologies (ERP and e-business) is to enable the extended value chain. 2.9 The value chain selected and customised for the purpose of this study This study involves Porter's value chain, Walters and Lancaster's value chain, the e-business value chain, the Scott value chain and the customer-centric value chain as discussed at the beginning of this chapter. The reasons for selecting these value chains respectively are given below.

Porter's value chain model is one of the foundation concepts on

which most ERP systems are built. 41 of Porter's value chain with Axapta Microsoft software modules and configuration as motivated in chapter 1.

CHAPTER 3: AN OVERVIEW OF ERP SYSTEMS

+ Web-enabled + 49 Source: Adapted from Blasis & Gunson (2002:17). For many users, an ERP system is a «do it all» that performs everything from sales orders to customer service. Others view it as a data bus with data storage and retrieval capability. In addition, Gardiner, Hanna and LaTour (in Shehab, Sharp, Supramaniam & Spedding, 2004:8) point out that an ERP system can be used as a tool to help improve the performance level of a supply chain network by helping to reduce cycle times. Boykin (in Shehab et al., 2004:8) argues that an ERP system is the price of entry for running a business and for being connected to other organisations in a network economy to create B2B and electronic commerce. ERP brought about the myriad of interconnections, which ensure that any other unit or department within the organisation can obtain information in one part of the business. This makes it simpler to see how the business as a whole is doing. ERP systems help people eliminate redundant actions, analyse data and make better decisions (Sweat in Gupta, 2000:115). An ERP system is the information pipeline system within an organisation which allows the organisation to move internal information efficiently so that it may be used for decision support inside the organisation and communicated via e-business technology to business partners throughout the value chain (Balls et al., 2000:186). In addition, Siriginidi (2000:378) defines ERP as an integrated suite of application software modules, providing operational, managerial and strategic information for organisations to improve productivity, quality and competitiveness. From the above definitions, it can be concluded that an ERP system can be regarded as an integrated organisation-wide software package that uses a modular structure to support a broad spectrum of key operational areas of the organisation. It provides a transactional backbone to the organisation that allows the capture of basic cost and revenue related movements of inventory. In so doing, ERP affords better access to management information concerning business activity, showing actual sales and cost of sales in a real-time fashion (Adam & Carton, 2003:22). The full installation of ERP software across an entire organisation connects the components of the organisation through a logical transmission and sharing of commonalties. Therefore, in this interface the data such as sales becomes available at any point in the business, and it courses its way through the software, which automatically calculates the effects of the transaction on areas such as manufacturing, inventory, procurement, invoicing and bookkeeping (Balls et al., 2000:12). Clemons and Simons 50 (2001:207) state that ERP is a term used to describe business software that is multifunctional in scope, integrated in nature and modular in structure. Indeed, ERP systems are designed for multisite, multinational companies, which require the ability to integrate business information, manage resources and accommodate diverse business practices and processes across the entire organisation. In support of the above view, Wood and Caldas (in Adam & Carton, 2003:22) found in their survey of 40 organisations that had implemented ERP that the main reason for doing so was the need to "integrate the organisation's processes and information". 3.4 The general model of an ERP system compared to a value chain system According to McAdam and McCormack (2001:116), the concept of integration within the functions of an organisation can be represented by Porter's value chain model as depicted in figure 2.1. Porter looked at the organisation as a collection of key functional activities that could be separated and identified as primary activities (inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, marketing and sales, and service) or support activities (infrastructure, human resource management, technology development and procurement). Porter arranged these activities in a value chain. Maximising the linkages between the activities increases the efficiency of the organisation and the marginal availability for increasing competitive advantage or for adding shareholder value. Integration occurs between the primary activities in each value chain, and is enabled by the support activities. It can also take place between activities in different organisations, and in some cases, the support activities also share resources. Thus, ERP systems aid the integration of these various functional processes within the organisation's value chain. Figure 3.2 below represents the general model of ERP systems and execution, integrated functionality and the global nature of present-day organisations in the different functional activities format of Porter's value chain model in figure 2.1. In figure 3.2, the circle at the centre represents the entities (organisation, payroll/employees, cost accounting, general ledger, job/project management, budgeting, logistics and materials, etc.) that constitute the central database shared by all functions of the organisation. The border represents the cross-enterprise functionality (multiplatform, multimode manufacturing, electronic data interchange, workflow automation, database creation, imaging, multilingual, etc.) that must be shared by all systems. The cross-organisation borders would be multifaceted, act as multifacilities and represent the capability required by the organisation to compete and succeed globally. It is important for the system's total solution to support multiple divisions or organisations under a 51 corporate banner and seamlessly integrate operating platforms as the corporate database that results in integrated management information (Siriginidi, 2000:379-80). The co-ordination performed by information system integration (ERP system) within the organisation's value chain enables more views to be shared, employee awareness to be broadened and customer expectations to be tracked and met (Bhatt, 2000:1331) Figure 3.2: The general model of an ERP system

Source: Adapted from Siriginidi (2000:380). The emphasis is further placed on the fact that the heart of any ERP exercise materialises in the creation of an integrated data model. Approaching it holistically, the ERP and execution model and its flexible set of integrated applications keep operations flowing efficiently. It should be looked upon as the acquisition of an asset, not as expenditure. An ERP system as a business tool seamlessly integrates the strategic initiatives and policies of the organisation with the operations, thus providing an effective means of translating strategic business goals to real-time planning and control. In order to achieve the integration of all the basic units of the business transaction, ERP systems rely on large central relational databases. This architecture represents a return to the 52 centralised control model of the 1960s and 1970s (Stirling, Petty & Travis, 2002:430), where access to computing resources and data was very much controlled by centralised IT departments. Therefore, ERP implementations are an inherent part of a general phenomenon of centralisation of control in large businesses back to a central corporate focal point (Clemons & Simons, 2001:207). 3.5 The role and benefits of an ERP system According to Ming, Fyun, Shihti & Chiu (2004:689-90), ERP systems have developed beyond their originally design intended to provide organisations with integrated, consistent and concurrent information that is available across the organisation. Integrated with electronic data interchange, it is used to streamline business processes in vertical markets, giving organisations the control and management of their resources. Furthermore, ERP systems provide a platform for integrating applications such as executive information system data mining, SCM, CRM and e-commerce systems. The real benefits of ERP systems currently are associated with the arrival of Web applications, which facilitate ERP systems to extend to electronic markets integrated with supply chains through B2B e-hubs. It further also extends to partners to integrate their own operations with other functions and to manage, monitor and execute all transactions in real time. An ERP system is considered to be the price of entry into B2B, e-market and other organisations in a network economy. Davenport (in Adam & Carton, 2003:24) shows the paradoxical impact of an ERP system on organisation and culture. ERP systems provide universal, real-time access to operating and financial data, and allow the organisations to streamline their management structures, creating flatter, more flexible and more democratic organisations. ERP systems also involve the centralisation of control over information and the standardisation of processes, which are qualities more consistent with hierarchical, command and control organisations with uniform cultures. Indeed, ERP systems help organisations in cross-organisation application integration, where the organisations can link their ERP systems directly to the disparate applications of their suppliers and customers. Therefore, such integration benefits the organisation in the following ways, which have been emphasised by Gupta (2000:115-6):

53

CHAPTER 4: A CASE STUDY OF ERP SYSTEM - AXAPTA

MICROSOFT

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

80

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

Source: Adapted from Axapta Microsoft software base study: available online.

4.6 The generic modules of Axapta Microsoft solution

The Axapta software solution offers the full breadth and functionality equivalent to other high-end products. A complete listing of Axapta's modules is provided below:

· Financial management - Comprehensive accounting, financial reporting and analysis. 81

· Business analysis - Helps an organisation to create, view and understand multidimensional reports.· Object server - Technology that minimises bandwidth requirements and offers secure client deployment.

· Tools - These allow almost every aspect of Axapta to be tailored, including user screens, reports, statements, tables and fields.

· Commerce gateway - Supply chain solution.

· Enterprise portal framework - Workflow is made smoother by allowing employees, customers, vendors and other business partners to interact directly with an organisation's ERP system.

· HR balanced scorecard - Business performance can be monitored based on key performance indicators.

· HR business process management - Business processes can be developed and managed by identifying and monitoring actions.

· Human resource management I - Helps gather and structure employee information.

· Human resource management II - Automated recruitment processes and employee absence analysis.

· Human resource management III - Resources can be developed to meet strategic goals.

· Logistics - Purchasing, production, customer demand, inventory and other key areas of other business can be streamlined.

· Master planning - Product forecasts are produced to project long-term needs for materials and capacity.

· Product builder - Web-based product configuration, allows for configuration of complex products.

· Production - Production I: Handles the material flow from suppliers, through production, to customers. Organisations can plan and execute routes, operations and do rough capacity planning. Includes operation management and detailed production scheduling.

· Shop floor control - Personnel and production can be managed. Tasks, time and material are registered via bar codes. Definitions of non-productive time are created and management can obtain an overview of who is doing what, and when.

82

· Trade - Automated sales and purchasing, exchange sales and purchasing information electronically (in combination with the commerce gateway module). System automatically calculates tax and cheks inentory and customer credit information. Picking and receiving documentation is automatically generated. Automatic tracking of back orders. Automatic unit conversions.· Warehouse management - Warehouses can be managed according to individual needs. Warehouse layout is optimised to increase efficiency. The warehouse can be divided into zones to accommodate different storage needs. Warehouse locations can be specified on five levels: warehouse, aisle, rack, shelf and bin. Helps the organisation to find the optimal storage location.

· Project - Project I: Time, materials and supplies consumption is entered, and projects and financial follow-up are managed for shorter-term time and material projects and internal projects. Project II: Advanced financial management for longer-term time and material projects, internal project, and fixed-price projects.

· Marketing automation - Specific audiences are targeted. Prospect information can be used to segment organisation target audience into meaningful profiles. An organisation can add and remove targets to meet its exact requirements and import address lists.

· Questionnaires - Online surveys, such as customer or employee satisfaction, can be designed in a matter of minutes, without any technical experience. Searches can be done for survey participants in system by criteria, for example job title. Surveys and results are made available via intranet or public website.

· Sales management - Individuals, teams and the entire organisation can be managed and monitored. Sales targets for individuals, teams and the company can be defined. The system tracks progress of activities, including pending sales quotes and generate forecasts.

· Sales force automation - Contact management can be streamlined. One centralised place provides a quick status of customers, prospects, vendors and partners. The system automatically detects incoming phone numbers and finds the contact card. Transaction log gives the organisation an overview of who has been in contact with a prospect or customer and what has been done. The system supports mail merge files and group e-mails.

· Telemarketing - Telemarketing campaigns can be managed. Call lists are generated by selecting fields, such as sales district, revenue, relation types, segment and past sales behaviour. Call lists can be distributed to salespeople and telemarketing staff. Questionnaires and

83

telemarketing scripts can be attached to call lists and call logs can be used to check the status of calls and create reports and future lists.

· Sales and marketing - Helps the organisation to access relevant sales information and instant cost-benefit analyses of revenue for executed campaigns. Gives the entire organisation access to contact information. Forecasts based on anticipated sales can be made.4.7 Conclusion

The Axapta Microsoft software discussed in this chapter will be compared with the literature review in chapters 2 and 3 in order to highlight the qualitative outcome of this study in chapter 6.

The next chapter (5) deals with the research methodology used in this study.

84

5.1 Introduction

In this chapter the methodology and research design utilised in this study are described. The type of research, the population, the data collection, as well as the sampling methodology and procedures, and data analysis used in this study is also outlined. Included in this chapter are the description of the methods used to collect the qualitative and quantitative data relating to the objectives and hypotheses formulated in this study.

5.2 Qualitative and quantitative study

This study involved both quantitative and qualitative research. Kruger and Welman (2002:191) stipulate that qualitative research is not concerned with the methods and techniques to obtain appropriate data for investigating the research hypothesis, as in the case of quantitative research. Qualitative data is based on meanings expressed through words and other symbols or metaphors. Qualitative studies can be used successfully in the description of groups (small) communities and organisations by studying cases that do not fit into particular theories. Thus, in this study qualitative research was applied to compare the different ways in the literature of linking strategy with IT through the value chain approach, and the general theory of ERP systems with the Axapta Microsoft software information. The quantitative research dealt with the factors associated with IT strategy, the ERP concept, usage and selection. This data was obtained through mail survey questionnaires in order to investigate some of the research objectives and hypotheses of this study (see table 5.2).

For the qualitative part of this research, the literature review dealt with the primary objective, as well as secondary objectives 1, 2, 3 and 4. For the empirical part of this research, the study involved a self-administered survey, which attempted to highlight the primary objective, as well as secondary objective 3 and hypotheses 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6 (H1, H2, H4, H5 and H6) to answer the overall hypothesis 3 (H3) of this study. Objective 5 is linked to chapter 7.

5.3 Research design

According to Kruger and Welman (2002:94), the design of a study concerns the plan to obtain

appropriate data for investigating the research hypothesis or question. Data collection tools for

surveys include interviews and questionnaires. In this study interviews allowed the researcher to85

clarify answers and follow up on interesting answers, while questionnaires were designed to be self-administered, since they can be mailed to a larger number of respondents. This short-dissertation was conducted using primarily a case study, which laid the foundation for the exploratory and empirical study. Interviews were used to explore the organisations using ERP systems, i.e. SAP software. Secondary to this, the researcher conducted an exhaustive literature review of the research topic. This involved the study of appropriate textbooks and conference papers, and the maximal use of Web-based documents that were used in the discussion of literature assessed in the case study. The study falls into the category of descriptive research, which aids in accommodating larger sample sizes, thus giving the research findings more generalisability than those of exploratory or qualitative designs (Hair, Buch & Ortinau, 2003:256).

Melville and Goddard (1996:44-5) point out that non-returns are a particular problem with questionnaires. Repeated follow-ups are most effective for reducing the non-response rate. Most research in the world is hampered by constraints of resources, subjects and time. Furthermore the researcher's work is complicated by many sources of bias and error that must each be dealt with as effectively as possible to ensure the high quality of the research (Bless & Higson-Smith, 1995:79). Thus, in this study, the researcher dealt with the non-response rate through the follows-ups. Non-respondents were contacted by telephone to remind them about the questionnaires that they had been asked to complete.

5.4 Methods of collecting quantitative data

The researcher chose self-administered surveys and structured telephone interviews to achieve the research objectives of this study. Hair et al., (2003:265) note that a self-administered survey is a data collection method where respondents read the survey questions and record their responses in the absence of a trained interviewer.

In this study, the researcher first conducted an exploratory telephone interview survey to identify the participants, especially the MNEs operating with any ERP system software. From that, the researcher contacted the key informants by telephone, most of them IT managers, to explain the purpose of this study. Respondents were also asked for their participation in the survey, which therefore allowed the researcher to compile the list of companies that use ERP software. These companies were used in the self-administered survey (see appendix E).

86

The participants in the survey of this study were CEOs/CIOs, managers (general, senior, middle and junior) and the end-users in the MNEs that use ERP, i.e. SAP software. The questionnaires were distributed to the IT human resource department in the nominated companies. For some of the MNEs, questionnaires were distributed through the general human resource department.

In total, 11 MNEs using SAP software were identified during the preliminary structured telephone interview survey. Only five MNEs using SAP software in Gauteng were involved in the self-administered surveys. The limited number was owing to budget constraints (see appendices D and E).

The researcher chose Axapta Microsoft solution from the available ERP software to be included in the qualitative study for several reasons:

· Firstly, it is designed for MNEs and has the ability to integrate the value chain so that the organisation can act globally and increase competition.

· Secondly, it is one of the leading ERP software systems in the world for manufacturing and service organisations.

For the quantitative study, SAP software was selected owing to its popularity and utilisation in the MNEs randomly selected through the preliminary structured telephone interview survey conducted by the researcher, as indicated in table 5.1 below.

Table 5.1: The usage of ERP software in randomly selected MNEs

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|||

Source: Obtained from the preliminary structured telephone interview survey conducted by the researcher.

87

5.5 Sampling method and sample size

5.5.1 Sampling method

Sampling is defined as the selection of a small number of respondents from a larger defined target population, assuming that the information gathered from the small group will allow the researcher to make generalisations or judgements concerning the larger group (Hair et al., 2003:333). According to Kruger and Welman (2002:46), there are two sampling designs:

· The probability sample involving simple random samples, stratified random samples, systematic samples and cluster samples; and

· The non-probability sample involving accidental or incidental samples, purposive samples, quota samples and snowball samples.

In probability sampling, the probability that any element or member of the population will have to be included in the sample can be determined. This is not the case in non-probability sampling. Considering the advantages and disadvantages of the sampling methods discussed above, it was concluded that a probability sampling design involving simple random samples had to be implemented in this study to compile the representative samples of employees in the MNEs. The researcher selected five out of eleven MNEs from a random list of the organisations using SAP in Gauteng (appendix E). By focusing only on these organisations in one province, the sample constituted a good representation of the organisations operating in Gauteng with a total turnover of nearly R1 billion per annum. Most of these organisations have been classified in the sector of financial services and manufacturing.

5.5.2 The sample size

The sample size of this study consists of five MNEs. In total 75 self-administered surveys were issued to each MNE, with the total sample size (N) equal to 375 participants. (One self-administered survey targeted one CEO/CIO with N = 1; one self-administered survey targeted managers (general, senior, middle and juniors) in each MNE with N = 30, and 44 end-users of the IT department of each MNE, N= 44). See table 5.3 (Response rate to the self administered survey).

88

5.6 Questionnaire design for the quantitative study

A questionnaire is a tool for collecting information to describe, compare or explain knowledge, attitudes, behaviours and/or socio-demographic characteristics of a particular target group (Rojas & Serpa, n.d.). The questionnaire used in this study to collect primary data was designed in accordance with the primary and some of the secondary objectives and research hypotheses proving the overall hypothesis 3 (H3) of this study, as will be discussed in more detail in chapter 6. The researcher compiled the questionnaire in accordance with seven basic principles of questionnaire design and layout (Dillon, Madden & Firtle, 1993:304).

The principles are as follows:

· Principle 1: Be clear and precise.

· Principle 2: Response choices should not overlap and should be exhaustive.

· Principle 3: Use natural and familiar language.

· Principle 4: Do not use words or phrases that show bias.

· Principle 5: Avoid double-barrelled questions.

· Principle 6: State explicit alternatives.

· Principle 7: Questions should meet criteria of validity and reliability.

The empirical data collection was structured and subdivided into two separate questionnaires (see appendices A and B).

· Firstly, a questionnaire was designed to target the CEOs or CIOs to get their views on the strategic part of the system within their organisation.

· Secondly, a questionnaire was designed to target the managers and the end-users in order to get

their views on the management and operational aspects of the system, its usage and awareness.Table 5.2 contains a summary of the objectives and hypotheses as linked to the questions used in the questionnaire.

89

Table 5.2: Relationships between questions in self-administered questionnaire survey and the primary and secondary objectives and research hypotheses.

· Questions linked to the primary and secondary objectives

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|||

· Questions linked to hypothesis

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|||

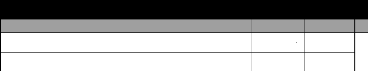

5.7 Response rate

The three-page questionnaire was mailed to every participant (CEOs/CIOs, managers and end-users), resulting in a total of 375 questionnaires. Therefore each of the five MNEs received 75 questionnaires. In total only three MNEs returned the completed questionnaires, with a total response of 137 constituted of 3 CIOs, 61 managers and 73 end-users (In some of the statistical analysis in the chapter six, the missing value were found therefore N value vary between 134 and

90

137). The total response rate therefore was 36.53 % of the sample (137 of the questionnaires returned out of 375 questionnaires issued).

Table 5.3: Response rate to the self-administered survey.

· Sample population

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

· Sample response

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

· Response rate

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|||

91

5.8 Data analysis

The different measuring instruments of mean, mode, standard deviation and so on were used to analyse the data collected (see appendices G and H). Furthermore, statistical analysis through chi-square was conducted to test the relationships between the hypotheses formulated (H0 and H1) in cross-tabulation with the different questions formulated. Fisher's exact test exact significance (one-sided) value was used as the p-value in this study. In cases where the p-value was less than 0.05, the hypothesis was rejected. If the p-value was greater than 0.05, the hypothesis was accepted.

5.9 Conclusion

This chapter dealt with the various methods and techniques used to collect the data in this study. An overview of the self-administered questionnaire as the specific measuring instrument was also provided. Reference was made to the sample size, the population of this study, as well as the detail of the interdependence of the questionnaire and the primary and secondary objectives and hypotheses of this study for the empirical part of the research.

The chapter to follow (chapter 6) will provide the qualitative and quantitative findings of this study relating to the various hypotheses proposed in chapter 1.

92

6.1 Introduction

While the previous chapter described the methodology and research design utilised in this study, this chapter outlines the finding of the qualitative study relating to the primary and some of the secondary objectives as indicated in the previsious chapter. The findings are related to the literature review (linking strategy with IT through a value chain approach, and the ERP system), with Axapta Microsoft software attributes given in the case study. The findings of the empirical study conducted through self-administered questionnaires are also represented in a similar order as given in the measuring instrument.

6.2 Qualitative findings

The findings of the qualitative study indicate that Axapta software is a value chain system that meets the requirements of a global ERP system due to its configuration and architecture under MNE strategy. It was found that its integrated status, which encompasses ERP system attributes and characteristics, its functionalities, modules and open system function with e-business mechanisms help to integrate, co-ordinate and leverage the MNEs' value chain. Cost leadership and differentiation strategy elements within Axapta software also position it as a strategic IT tool, which therefore supports the MNEs in crafting their business strategy to gain competitive advantage.

6.2.1 Axapta software integrates MNEs' value chain and supports MNEs' strategy

The Axapta Microsoft software is consistent with the concept of competitive business strategy as discussed by Turban et al., (2004a: 6) in section 2.2. These authors stipulate that IT can help any business to pursue competitive strategies by developing new market niches, locking in customers and suppliers by raising the cost of switching, providing unique products and services and helping organisations to provide products and services at a lower cost by reducing and distributing costs.

According to Ward and Griffiths (in Corboy, 2002:7) and Siriginidi (2000:376), IT can be used to gain competitive advantage because of its capabilities and status of linking the organisation to the customers and suppliers through EDI, VANs and extranets, creating effective integration of the use of information in a value-adding process, enabling the organisation to develop, produce, market and

93

distribute new products or services and provide senior management with information to assist them to develop and implement strategies through knowledge management. See section 2.3.

Axapta software can be used as a strategic IT tool within MNE management because it improves co-ordination, collaboration and information sharing, both within and across the various organisation's sites, and integrates the management information processes and applications within the MNE's operations. (See sections 4.4, 4.5 and 4.6.)

· Axapta's various functionalities and the Internet allow MNEs to collaborate and connect with their customers, vendors, partners, or employees via the Web, Windows, WAP, wireless, VAN, LAN, XML and Microsoft BizTalk. It allows MNEs to exchange information with others through ERP software in their IT infrastructure, such as a parent company, subsidiary or supplier.

· The selected key features are speed, customisation options, multiple databases, worldwide features, all-in-one products, foreign language and foreign currency, built-in remote access and questionnaires.

· The generic modules of Axapta consist of Financial management, Business analysis, Object server, Tools, Commerce gateway, Enterprise portal framework, HR business process management, Human resource management I, II and III, Logistics, Master planning, Product builder, Production, Shop floor control, Trade, Warehouse and sales management, Project, Marketing automation, Questionnaires, Sales force automation, Telemarketing and Sales and marketing. The modules could be customised to suit the MNE structure and objectives.

Axapta attributes include programming language (Java-derivative with embedded SQL support), database (either Microsoft SQL server or Oracle database), source code (MorphX), Web applications and the commerce gateway that provides an XML interface to the Microsoft BizTalk server as discussed in section 4.3. These attributes classify Axapta software's generic capabilities as a transactional and geographical automation and an analytical, informational and sequential system for MNEs. Therefore Axapta software is truly an ERP system, which provides a platform for integrating MNE applications such as SCM, CRM, executive information system data mining and e-commerce systems. Axapta thus conforms to the view of Aladwani (2001:266) that an ERP system is an integrated set of programmes that provides support for core organisational activities. Blasis

94

and Gunson (2002:16-7) state that an ERP system is a tool that grafts a solution for human resources, finance, logistics etc., and eventually to SCM and CRM, as discussed in section 3.3. Ming et al. (2004:690) and Davenport (in Adam & Carton, 2003:24) are of the opinion that an ERP system influences the cross-organisation application integration, where organisations can link their ERP systems directly to the disparate applications of their suppliers and customers. Such integration benefits the organisation due to its current associated trends. Axapta fulfils these requirements as well. (see section 3.5.)

Axapta software could support MNEs' value chain internationally since it has centralised, distributed and hybrid architecture as mentioned by Clemons and Simons, and Zrimsek and Prior (in Madapusi & D'souza, 2005:10). Axapta software can be configured and customised according to the MNE strategy at organisation, system and business process level (see sections 3.7.1 and 3.7.3). Thus, through the MNE's strategy, Axapta architecture is multifunctional and can be customised and parameterised to suit the MNE with distributed information architecture, a stand-alone local database and application as options.

6.2.2 Strategic factors of an ERP system evaluation

To meet the requirements of the MNE's value chain system, ERP software needs to be evaluated in terms of its modules and functionality. It must also be possible to configure the different ERP software systems with different modules, thereby making it look different from others (Sarkis & Sundarraj, 2000:205). A typical set of business functions supported by an ERP system as the supply chain factors for ERP software evaluation was summarised in section 3.8. Sarkis and Sundarraj (2000:205) have integrated those evaluation factors into one conceptual model, shown in figure 3.3, to explain the linkage and the relationship of all processes and functions within the supply chain through an ERP system, allowing communication between the different activities to take place. A comparison was made between Axapta software attributes and functional modules (section 4.6) and general ERP system modules and business functionality (section 3.8). Table 6.1 below indicates that Microsoft has made Axapta software with various functional modules in its package to meet the general conceptual model of an ERP system, which can be depicted in different activities and processes, standardised and customised to suit the MNE. An ERP system has a large central relational database, which allows the sharing of all the information within the MNE's departments through the execution, integrated functionality and global nature of the system. Other characteristics

95

are the multiplatform, multimode manufacturing, electronic data interchange, work automation, database creation, imaging, multilingual and modules as noted by McAdam and McCormack (2001:116), Siriginidi, (2000:379-80), Bhatt (2000:1331), Stirling, Petty and Travis (2002:430) and Clemons and Simon (2001:207) in section 3.4. Thus, Axapta as an ERP system matches the view of Siriginidi (2000:379-80), who stipulate that the general model of an ERP system must be a system's total solution to support multiple divisions or organisations under a corporate banner and seamlessly integrate operating platforms as the corporate database that results in integrated management information. In addition, Axapta also corresponds with the views of Shehab et al., (2004:361) in section 3.6.2, who state that ERP systems are all based on a central, relational database, built on a client/server architecture and consist of various functional modules.

Table 6.1: General ERP system modules compared to Axapta software package modules

|

ERP system modules |

Axapta software modules |

||

|

1. Business planning |

1. Axapta business planning |

||

|

2. Enterprise performance measurement |

|

|

|

|

3. Tools, Project I and HR business process management |

|||

|

4. Marketing and sales |

4. Marketing automation, Sales and marketing, Sales force automation and Sales management |

||

|

5. Manufacturing |

5. Master planning, Production I and Shop floor control |

||

|

6. Finance and accounting |

6. Financial management and Project II |

||

|

7. Engineering |

7. Product builder |

||

|

8. Human resources |

8. Human resource management I, II and III |

||

|

9. Purchasing |

9. Trade |

||

|

10. Logistics |

10. Logistics and Warehouse management |

||

|

11. After-sales services |

11. Object server, Telemarketing and Questionnaires |

||

|

12. Information technology |

12. Enterprise portal framework, Integrated and Web- enabled business logic, Internet, Commerce gateway and object server |

||

Source: Dykstra and Cornelison, and Olinger (in Sarkis & Sundarraj, 2000:206).

96

6.2.3 Summary (sections 6.2.1 and 6.2.2) for hypothesis1 (H1)

With regard to hypothesis 1 (H1), and the questions asked in section 2.5 were whether Axapta software supports strategic management within the MNE and whether Microsoft has positioned Axapta competitively. These issues will assist MNE management in crafting a strategy aimed at establishing a sustained competitive strategy. The following can be stated:

Hypothesis 1 (H1) is not rejected and it can therefore be concluded that Axapta software is an ERP system with an integrated value chain system due to the elements discussed above (in section 6.2.1) and in sections 6.2.5.1-2, 6.2.5.3-4; 6.2.5.5 and 6.2.5.6 below. Axapta modules also suit the strategic factors of an ERP software evaluation as discussed in section 6.2.2. Furthermore, Axapta has various advantageous elements incorporated, as discussed in section 3.5.1, such as Y2K compliance, ease of use, integration of all functions, online communication with suppliers and customers, customisation, improvement of decision-making due to the availability of timely and appropriate information, improved process time and feasibility of administering pro facto control on the operations and Internet interface (Gupta, 2000:115-16). Axapta characteristics (in section 3.5.2) are that it is flexible, comprehensive, with modular and open systems, operating beyond the organisation, capable of simulating the reality and with a multiple environment.

The integrated configuration and the e-commerce functionality as core competence within Axapta software could support the MNE's strategy management due to its cost leadership and differentiation strategy, local hardware requirements, the involvement of maximum use of LANs and minimal use of WANs, the autonomy of each local unit, and headquarter linkage, which occurs primarily through financial reporting structures (section 3.7.3). Axapta software could influence the MNE to integrate the business process activities across its value chain functions, enabling the implementation of all variations of best business practices with a view towards enhancing productivity, operation efficiency, sharing common data and practices across the entire organisation to reduce errors, produce and access information in a real-time environment to facilitate rapid and better decisions and cost reduction (see section 3.6.2).

As mentioned in section 2.5, Turban et al.,

(2004a: 16) discuss the cost leadership and

differentiation strategies. A

cost leadership strategy focuses the organisation's attention

on

manufacturing scale and efficiency that exhibit the capital investment,

process engineering skills,

97

intense supervision, design for manufacturing, low-cost distribution systems, tight cost controls, frequent and detailed cost reports, high specialisation and incentives based on quotas for organisation management. Differentiation strategies focus on select product or service attributes that customers deem important and create value by supplying products and/or services with the desired attributes. To achieve success with a differentiation strategy, an organisation must differentiate between product or a service attribute different from those chosen by industry rivals (Porter, 1998:10). Therefore, a differentiation strategy is most likely to produce an alternative and lasting competitive edge when it is based on technical superiority, quality, giving customers more support services and the appeal of more value for money (Thompson & Strickland, 1987:110).

In answer to the question asked at the start of this summary section, Microsoft has indeed positioned Axapta software with cost leadership and differentiation strategies due to the attributes incorporated in the Axapta package (sections 4.2, 4.3, 4.4, 4.5 and 4.6). Axapta is a low-cost leader software among the different ERP system software in the market. It has also differentiated itself from other software in its value proposition (the quality, competitive price and the product and service attributes) and key success factors such as customer value distributors as shown in Walters and Lancaster's value chain below (section 6.2.5.2). These strategic elements constitute the forces that contribute to the MNE's competitive position and that persuade the MNE management to perform the activities differently than the competitors and link those activities in the value chain to craft its strategies for competitive advantage.

However, behind the cost leadership and differentiation strategies, other strategic elements are associated with Axapta software (section 2.5); elements which could support the MNE's strategy to gain competitive advantage. These are:

· The niche strategy: Axapta has a niche market with a quality product, low-cost price, fast, multiple databases and other selected key features.

· The alliance strategy: alliance is achieved through Microsoft SQL server or the Oracle database.

· The innovation strategy: Axapta has key features to meet the current global ERP system requirements and MNE growth.

· The locked-in customer or suppliers strategy: Axapta software links customers and suppliers through integrative modules in its module package.

98

· The entry-barriers strategy: Axapta has created barriers to prohibit entry to other MNEs.In practical terms, Microsoft has increased the switching cost for Axapta software and thus created a barrier prohibiting entry to any competitor. This offers the MNEs the opportunity to expand their business and decrease supply costs, increase cost efficiency, build relationships with suppliers and customers within the MNEs and replace and add applications to meet the organisation's growth and changing partners. In this way Axapta attributes could assist MNE management in crafting strategy accordingly.

6.2.4 Axapta's software evaluation

A strategic IT plan is a decision-making process that should be undertaken with care, systematically and within an organisation's understanding of the business context (see section 2.4). Therefore, by applying Axapta software attributes as discussed in chapter 4 through strategic IT plan evaluation, the MNE management could achieve efficiency in the overall management operation in the same context as noted by Peppard (in Corboy, 2002:6), namely by establishing entry barriers which affect the cost of switching operations, differentiating products/services, limiting access to distribution channels, ensuring competitive pricing, decreasing supply cost, increasing cost efficiency, using information as a product and building closer relationships with suppliers and customers.

6.2.5 Axapta's value chain system

In chapter 1 (section 1.1.3) it was pointed out that the value chain model can be used to evaluate relative position, identifying an organisation's distinctive competence(s) and directions for developing competitive advantage. In addition, IS has an impact on an organisation's individual value chain and on how the integration between the value systems of the various contributors or activities could be strengthened, as well as on the cost/value of the product (Axapta), users (MNEs), manufacturer (Microsoft) and customers. The value chain can be used to evaluate a company's process and competencies, and investigate whether IT supports add value, while simultaneously enabling managers to assess the information intensity and role of IT. Thus, the value chain approach was positioned as an evaluative tool to assess Axapta's attributes (as the product) and MNEs (as the user), and Microsoft (as the manufacturer) in order to answer the hypothesis formulated in the introduction and scope of this study.

99

In chapter 2, the theory behind the value chain system was analysed relating to the different models. This led the researcher to suggest that most ERP systems, including Axapta software, were built on the value chain concept. A value chain assists management in crafting a strategy (section 2.6). It was concluded that the value chain is based on the linkage, co-ordination and interrelationships among the activities within the system. Thus, Axapta could be assessed by means of the value chain approach to test if its attributes and architecture suit the different value chains in the MNE strategy context. The customised value chain (section 2.9) led to the following findings:

6.2.5.1 Porter's value chain and Axapta's value chain architecture

The primary activities of Porter's value chain are inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, marketing, sales and service. The support elements are procurement, technology development, human resource management and infrastructure (see figure 2.1 in section 2.7.1). The key features of Axapta, namely manufacturing, distribution, SCM, project management, financial management, CRM, human resource management, business analysis, global solution and technology, can be compared with the activities of the Porter value chain (section 4.5), as well as Axapta's generic module activities.

Figure 6.1: The module activities of Axapta depicted in the Porter value chain

Secondary activities

Firm infrastructure

(Accounting, Finance, General management, Business analysis and tools)

Technology development

(Product builder, Web-enabled application, ERP, Internet, Commerce gateway, etc.)

Human resources management

(Employee information and registration, recruitment processes, etc.)Procurement

(Supply chain, Electronic information exchange)

Value

Inbound

logisticsOperations

Outbound

logistics(Warehouse management, Logistics, Distribution)

Services

Marketing and

sales

(Master planning,

Shop floor control,

Project I)(Productions, Manufacturing)

(Global solution, Service management, Object serve, Distribution)

(CRM, Sales force marketing, Automation, Customer self-service, websites Sales management)

Primary activities Primary activities

Upstream value activities Downstream value activities

100

Source: Adapted from Porter ' value chain in Turban et al., (2004a: 11).

The depiction of Axapta activities shown in brackets in figure 6.1 above proves indeed that Microsoft has incorporated Axapta's value chain system with its different activity processes and modules in Porter's value chain in order to strengthen, support and position the MNE's value chain activities to operate efficiently (see section 4.6).

6.2.5.2 Walters and Lancaster's value chain and Axapta's attributes

The reason for assessing the Axapta software value/cost drivers using Walters and Lancaster's value chain model and components (see figure 2.5 in section 2.7.4) was to analyse Axapta's capability, attributes, key features and functionality modules (see sections 4.2, 4.3, 4.4, 4.5 and 4.6). Microsoft as the manufacturer associated Axapta with the key success factors supporting the MNE supply chain integration and co-ordination in an MNE's operation activities. This maximises the customer and distributor values criteria and minimises customer acquisition costs.

As shown in figure 6.2 below, Axapta software has the value/cost drivers that enhance MNE business processes and integrate the different applications within the supply chain. It co-ordinates and strengthens the different activities in relationships to improve productivity and enable the MNE to operate globally and communicate efficiently. The elements associated with Axapta software are value/cost driver, logistics management, strong integrated company/dealer and supply network, cost management, service (distributors), service (customers), marketing automation, telemarketing, self-service website, Internet, customer and supplier involvement, management knowledge and CRM. Other elements that Axapta software has are global reach and online service, worldwide coverage, technologies applications, time responses and accuracy. Axapta relationship management elements are software support, management and staff development, open communication with providers, suppliers, dealers/company and co-ordination. Thus, Axapta information and relationship management creates the value strategy and positioning, which is linked with the value production and criteria that encompass both Axapta operations and organisation structure management.

In organisation structure management, the Axapta elements that assist MNEs in operating

efficiently and effectively are the control of manufacturing and service, the supply chain, staff

training, the partnerships with customers, suppliers and dealers, the integration of supply, selective101

outsourcing and ongoing customer surveys. In the operations structure and management, both production and logistics play an important role. The Axapta production drives include elements such as maintenance and repair, material requirement planning, the bill of material, capacity planning, job scheduling and sequencing, and IT-driven design and manufacturing. In Axapta logistics drives, the elements are global communication, IRIS information system, and supply chain integration, remote serviceability monitoring and quick response.

Figure 6.2: Axapta cost/value drivers depicted in Walters and Lancaster's value chain

Organisation

structure

management

Customer value criteria

· Brand name

· Competitive prices

· Flexible response (languages, time, culture)

· Reliable, easy to use

· Module selection,

customisation

Customer acquisition costs

· Easy installation

· Switching cost

· Worldwide distribution

· Servicing, consultant

possibility· Product reliability

Customer

value

(Distributor)

· Global reach

· "Online" service

· Worldwide coverage

· Technologies applications

· Time response

· Accuracy

· Software support

· Management and staff development

· Open communication with providers, suppliers, dealers, company

· Provider = company, i.e. long-term continuity

· Co-ordination

Information management

Value

strategy

and

positioning

Relationship

management

Value

production and

criteria

· Control of manufacturing, service, and the supply chain

· Staff training

· Partnerships with customers, suppliers and dealers

· Integrated

supply· Selective outsourcing

· Integrated

supply· Ongoing customer surveys

· Maintenance and

repair· MRPII, BOM

· Capacity planning

· Job scheduling and

sequencing· IT-driven design and manufacturing

· Global communication

· IRIS information

system· Supply chain integration

· Remote serviceability monitoring

· Quick response

Operations structure

and management

Production

Logistics

Value/

cost

drivers

Customer

value

Distributor/customer cost

criteria

· Customer field

support

· Company/distributor/ customer liaison: product and service

Value proposition

(product/service

attributes)

· Module differentiation

· Software customisation

· Flexibility

· Product substitution

· Service/advice

· Transaction convenience

· User capacity maximisation

· Quality, consistent costs and service

· Speed

· Integrated CRM

· Cost leadership

Distributor/customer value

criteria· Internationally recognised brand

· Company support: service and sales

· Worldwide response network

· Product market development

Key success factors

· Vertically integrated

supply chain· Innovation

· Economies of scale

· Strong marketing component modules

· Responsiveness,

speed· Integrated CRM, customer and supplier application strategy

· Cost-effectiveness

· Technical expertise

· Flexibility in manufacturing

· E-business components

· Supply chain and logistics management

· Strong integrated company/dealer and supply network

· Cost management: IT-controlled manufacturing activities and service

· Service (distributors): database and business analyses

· Service (customers): customised software, and low-cost

service

· Marketing automation and telemarketing

· Self-service website, Internet

· Customer and supplier involvement

· Management Knowledge, CRM

"Corporate value"

· Productivity

· Profitability

· Knowledge

· Cash flow

Source: Adapted from Walters and Lancaster (2000:163).

102

The value proposition of Axapta (product and service attributes) consists of modules of differentiation, which are incorporated in its package, software customisation capability, flexibility, product substitution, service/advice, transaction convenience, user capacity maximisation, quality, consistent costs and service, speed, integrative and the cost leadership. The Axapta corporate value consists of productivity, profitability, knowledge and cash flow. The key success factors (the vertically integrated supply chain, innovation, economies of scale, strong marketing component modules, responsiveness, speed, integrated CRM, customer and supply application strategy, cost-effectiveness, technical expertise, flexibility in manufacturing, e-business components) are the strategic elements enhancing the MNE's strategy. In the Axapta distributor customer cost criteria, Microsoft as the manufacturer and provider could assist the user (MNE) in customer field support and company/distributor/customer liaison. In addition to the Axapta distributor/customer value criteria, Microsoft is one of the top companies worldwide due to its internationally recognised brand, company support in service and sales, worldwide response network and product market development.

Customer value contributes to the key success factors of Axapta software. Axapta positions itself as one of the top ERP software systems in the market due to both customer value criteria and customer acquisition costs. The customer value criteria element of Axapta include reliance on the brand name, competitive prices, flexible responses (in languages, time and culture), reliability, easy to use, module selection with a customisation option, customer acquisition costs, installation, switching cost and worldwide distribution, servicing, consultant possibility and product reliability.

6.2.5.3 The customer-centric value chain and Axapta software

According to Slywotzky and Morrison (1997:17) (see section 2.7.2), customer-centric thinking is based on the identification of customer priorities and therefore constructs business designs to match them. Axapta software incorporates this customer-centric value chain approach. Microsoft has incorporated into Axapta software architecture features such as CRM, SCM, collaboration functionality and the distribution channel capabilities, shown in table 4.1. The Commerce gateway module promotes supply chain solutions and the Enterprise portal framework module allows customers to interact with some of the functions in the organisation's value chain via other modules (see section 4.6). Thus, Axapta software can allow any MNE to apply a customer-centric approach

103

due to the Product builder-Web-based product configuration, which allows configuring complex products to meet the customers' wants and needs.

6.2.5.4 Scott's value chain and Axapta software

The core elements of Scott's value chain as discussed in section 2.7.3 comprise seven areas: operation strategy, marketing sales and service strategy, innovation strategy, financial strategy, human resource strategy, information technology strategy and lobbying position with government. In the Scott value chain, co-ordination across the value chain is essential. To strategise its plans well, an MNE needs compatible ERP software with the various modules to support its objectives. Axapta software has different modules, as discussed in section 4.6, which can strategically enhance the MNE's business management. These modules are Operation strategy, Production, Logistics, Master planning, Shop floor control and HR balanced scorecard. For the marketing sales and service strategy, Axapta has the Trade and Commerce gateway, Marketing automation and Sales management, sales force automation, Sales marketing and Questionnaire modules.

To enhance innovation strategy, Axapta software includes Product builder and the financial management module to enhance the financial strategy. To enhance the human resource strategy within the MNE, Axapta has the modules of Human resource management I, II and III, which can help to gather and structure employee information, automate recruitment processes and employee absence analysis and develop resources to meet strategic goals. To enhance the IT strategy within the organisation, Axapta has incorporated HR business process management, which develops and manages business processes by identifying and monitoring actions, as well as the Tools and Enterprise portal framework modules. The modules are co-ordinated through Web applications, Commerce gateway provides an XML interface to the Microsoft BizTalk server, and the integrated e-commerce applications facilitate the relationships between the MNE's value chain activities across its SBUs. Axapta software configuration indeed meets the requirements of Scott's value chain.

6.2.5.5 Value nets and Axapta software value chain architecture

According to Bovet and Martha (2000:2-6), a value net forms itself around its customers, who are at the centre. It captures their real choices in real time and transmits them digitally to other net participants. It views every customer as unique and allows customers to choose the product/service attributes they value most (see section 2.7.5). With regard to Axapta software, Microsoft has built

104

Axapta software architecture and configuration in such a way that an MNE using it can customise the software in any way it wants, and co-ordinate its departments to work in relationships through digital collaborative system mechanisms due to Axapta key features such as speed, multiple databases, scalability, intercompany trade and electronic information exchange (see section 4.5). Thus, Axapta software is a value net (customer-aligned, collaborative and systemic, agile and scalable, fast-flowing and digital).

6.2.5.6 The e-business value chain model and Axapta software architecture

As seen above, the Axapta value chain system meets the requirements of Porter's value chain, its software is a value net and its software attributes and applications as discussed in chapter 4 enable MNEs to extend their value chain to all business partners due to e-business mechanisms. These mechanisms include e-commerce applications, the intranet and extranet, Web-based procurement and the Internet, user portals and supply chain automation. These factors influence the collaboration between organisations through e-marketplaces, in addition to improving SCM and CRM processes. Thus, the Axapta value chain lowers MNE costs and increases value in activity co-ordination and integration due to the adoption of e-commerce strategies. Axapta is therefore a virtual or electronic value chain (see figure 2.7). This strengthens the MNE's value chain system activities and processes due to the Internet-prominent application.

6.2.6 Summary (sections 6.2.3 to 6.2.4) for hypotheses 2, 4 and 5 (H2, H4 and H5)

Hypotheses 2, 4 and 5 (H2, H4 and H5) are not rejected and it can therefore be concluded that Microsoft has made Axapta software with all the modules, functionalities and key features discussed in sections 4.4, 4.5 and 4.6. It meets the requirements necessary for the basic foundation of an ERP system as pointed out in sections 6.2.1 and 6.2.2. In addition, the value chain concept architecture with IT mechanisms integrate the different applications as a net value digital system. This means that MNEs using Axapta can align their strategies with organisation management due to the IT capabilities within their value chain. This strengthens the processes and the relationships within the overall value chain locally and globally.

Axapta assessment through the value chain approach indicates

that Axapta value chain activities as

depicted in figure 6.1 of

section 6.2.3 are similar to Porter's value chain approach

(see section

2.7.1). This indicates that Microsoft has

positioned Axapta software with components and options

105

that are well structured to help MNEs to co-operate efficiently with their separate operating sites, and to integrate its various applications and modules. This strengthens MNEs' value chain processes and means that MNEs can act globally and respond quickly to a demand.

As seen above (section 6.2.3), value/cost drivers have been incorporated in Axapta software (section 2.7.4). This positions Axapta as a competitive ERP software tool due to its value proposition, and product and service attributes play a big role in terms of software standardisation, operation effectiveness and quality service promotion in the MNE by integrating and strengthening the different activities in its value chain system. Thus, Microsoft has made Axapta software capable of co-ordinating the raw material from supply to the transformation process, and to delivering the product or service to the customers. Axapta is able to integrate the supply chain and automation, and enhance logistics, which contributes to the effectiveness of the procurement and operation system, the knowledge of partnerships and the know-how of the provider. Microsoft also supports MNEs with training support and technical expertise, and substitution components to meet MNEs' changing and growth needs.

The assessment of Axapta software through Scott's value chain theory discussed in section 2.7.3, along with section 6.2.3 reveals that the software architecture favours the relationship between the MNE's value chain and its SBUs due to its customisation module, which could allow each of the MNE's SBUs to configure its activities.

A value net begins with customers, allowing them to self-design products and builds them to satisfy actual demand. Thus, Axapta software was positioned as a value net due to its digital, fast and flexible system that is aligned with and driven by customer choice mechanisms. In section 6.2.3, it was demonstrated that Axapta software has been modernised as a truly global ERP system due to the incorporation of the Internet applications within it, with the front-end e-business application for third parties. Thus, the Axapta software value chain will position MNEs to operate in the e-business environment. In addition, Axapta's attributes and requirements allow MNEs to incorporate front-end technology in their business operation, create trading communities through portals and take on joint ventures with Web-based technology in expanding the MNEs' value chain, thus benefiting all global users, suppliers, customers and organisation partners.

106

6.2.7 Axapta as an IT integrative tool for MNEs' value chain systems

Sections 6.2.1, 6.2.2, 6.2.3 and 6.2.4 revealed that Axapta is strategically IT tool, an integrative ERP software system and a value chain system due to its attributes and modules, which have functional and international architecture and configuration. This enables MNEs to integrate and enhance their supply chain operation more efficiently and effectively, resulting in greater value for the end-customer. Consequently, the tangible and intangible benefits of this value chain integration through Axapta software will be enormous for MNEs, as they allow the real-time synchronisation of supply and demand. The benefits will further be to provide support to an MNE in its efforts to become part of an extended organisation, operating beyond the electronic SCM environment. This has the effect of positioning the MNE to develop collaborative business systems and processes that can span across multiple organisational boundaries (Balls et al., 2000:82-4).

6.2.8 Summary (section 6.2.5) for hypothesis 6 (H6)

The question asked in section 2.11 was "Is Axapta software a value chain system with IT mechanisms, which facilitate the integration and the co-ordination of other ERP system applications?"