|

The United States is a great country that has always stood up

for democracy and helped when human rights were violated, so why is there still

the death penalty? In the context of the infamous Angel Nieves Diaz's case in

Florida, the execution of Saddam Hussein, the obligatory abolition of capital

punishment for new members of the European Union, and the new article of the

French Constitution proclaiming that no person can be convicted to the death

penalty, the death sentence is a very current issue which divides people and

arouses passionate debates. This is, after slavery, the most controversial

topic and a strong differentiating factor between the European mindset and the

American one. Indeed, while the European Union obliges its new members to

abolish the death penalty, the United States continues to pronounce this

sentence and execute people, making it one of the four countries to execute the

most people in 2005 (94% of the 2148 executions in 2005 took place in China,

Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United States).

Inside the country itself, the 51 States have very different

judicial systems and trial processes, according to the party in power, the

general local mentality, and the socio-historical context. Of these States, 38

administrations, the federal government, and the U.S. military still sentence

people to death. Among those jurisdictions, there are substantial differences

in the application. Based on this paper's findings, it appears that the South

uses this sentence more frequently, and also more discriminatorily.

The State of Texas in particular has the highest number of

executions and several specific cases which suggest that there is racial

discrimination present in the determination of the sentence.

Besides the ethical debate about whether it is just to kill

people, capital punishment also raises important concerns about miscarriages of

justice, condemned yet innocent prisoners, equal representation,

discrimination, and the role of the church and whether it has a deterrent

effect or not. Such questions have caused significant debate among academic,

legal, and political circles.

I chose this subject for many reasons. First of all, the

subjects of social and racial discrimination have always been very near to my

heart. My studies and personal experiences have opened my eyes to certain

injustices in the world. This awareness has inspired me to fight against such

inequity to the fullest extent of my ability. Having personally endured a life

and death experience, I can now fully appreciate the value of human life. I

simply cannot believe that someone or a group of people could end the life of

another person - especially in the name of justice (that is to say, «in

the name of the people»). In addition, I have seen many movies which

confront the death penalty in the United States, which I have included as

social references to study the various issues surrounding the issue. My

research has made me increasingly interested in, and impassioned by this

matter, driving me to attend the World Congress Against Death Penalty, in Paris

from the 1st to the 3rd of February 2007. It allowed me

to better understand the subject, and above all, to meet the people dedicated

to the opposition to the death penalty. I am currently in contact with Colette

Berthès, a French author and abolitionist activist, Bob Burtman, an

American lawyer specializing in death penalty cases in North Carolina, and Sean

Wallace, manager of the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty (United

States), where I will do an internship this summer. They have helped me

considerably, for which I am extremely grateful.

Throughout the research and the writing of this thesis, I have

realized how difficult it was to grapple with this topic, as this sensitive

issue touches upon personal convictions, ideals and emotions concerning life

and death. However, it also confronts ideas of religion, race, tolerance, and

forgiveness, while at the same time challenging and questioning a steadfast

United States judicial system.

I admit that being French and having strong political, social

and humanist predispositions - even with the best will in the world - suggests

a bias in this critique of American society and its application of the death

penalty. Indeed, in composing this essay my previous convictions on the death

penalty were reinforced. Nevertheless, it has also made me realize the

importance of social movements and the power of the dissenting voice. By

acknowledging at the start the possibility of bias, I have endeavored

throughout the duration of this report to remain as objective and unbiased as

possible.

This study is dedicated to examine the faults of the United

States judiciary machine.

The first part will provide an outline of the death penalty in

the United States in its historical context, and then briefly describe the

current criminal law systems at the State and federal levels. Then, the second

part will analyze geographical indicators concerning the application of the

death penalty. Finally, the third part will examine in depth the case study of

Texas, where it will highlight the drawbacks of the United States criminal law

system in light of its unbalanced judicial system, and provide a hypothetical

explanation for the geographical differences discovered between the separate

State systems.

I. Death Penalty in the United States

A. Historical analysis of the death penalty in

the United States

Death penalty has been applied in almost every civilization

throughout history. Geography, culture, politics and history have varied its

forms and the offenses for which it could be imposed. More precisely, this

evolution of capital punishment has varied from country to country, following

changes in history, social and political principles, as well as judicial and

political systems. Then in 1786, when the Duke of Tuscany passed the first law

abolishing the death penalty, the whole world started to question the

legitimacy of such a sentence. This was the starting point of the international

abolitionist movement, which accelerated throughout the twentieth century,

until by the early 1980s almost every democratic country had abolished death

penalty. By 2006, 97 countries had abolished capital punishment de jure

(including 86 for all crimes and 11 for crimes of common right), 34 had

abolished it de facto (by having not used it for 10 years) and 65

countries still had it in their laws and applied it1(*). Among these countries, the

United States is the only developed, democratic country continuing to use

capital punishment. Japan also sentences to death but executes fewer than six

offenders per year, whereas in The United States yearly executions have

exceeded 21 since 1983. U.S. execution frequencies are equivalent to those in

authoritarian states such as China or Iran. What is more, 94% of the executions

were carried out in four countries: China, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United

States.

1) First death penalty cases in the United

States

The apparition of the death penalty in America dates back to

the colonial period; it was introduced by the European settlers. Captain George

Kendall was the first recorded person sentenced to death in 1608, in the colony

of Virginia, for having been a spy for Spain. At that time, offenses and

punishments varied according to the colony, as they vary from state to state

today. In the New York Colony, for example, one could be sentenced to death for

offenses such as hitting one's father or mother or for denying the `true God'.

During the eighteenth century, with the Age of the Enlightenment, European

philosophers and intellectuals influenced reforms of death penalty. The

Italian scholar, Cesare Beccaria, laid the foundation of the modern conception

of the rights of criminals in 1764 in Crime and Punishment. Herein,

he provided the basis and the limits to the right to punish, and recommended

that the sentence be proportional, or correspond to the crime. In the United

States, the Declaration of Independence (1776) notably lists such fundamental

rights as the right to life, freedom and the pursuit of happiness. The

importance of these rights was confirmed in the Constitution, adopted in 1789,

which guaranteed democracy, the separation of powers, and the individual

liberties. The Bill of Rights, ratified in 1791, complemented the Constitution

with the first ten Amendments. Among them are the Fifth Amendment, which

defines the rights of the defendant during the criminal process and the trial;

the Sixth Amendment, which provides the right to a fair and rapid trial; and

the Eighth Amendment, which forbids any `cruel and unusual punishment'.

2) Evolution during the nineteenth century

From 1907 to 1917, six American states completely abolished

death penalty and three limited it to very few, grave, and rare offenses. But

the social unrest within the country and the context of World War I hardened

the judicial system. Gradually, the six abolitionist states chose to reinstate

death penalty, and there was a resurgence of executions between 1920 and 1940.

As can be seen in the following graph2(*), the 1930s marked the decade with the highest number

of executions, averaging 167 per year (a figure which dropped to129 in the

1940s, 71 in the 1950s, and fell yet again to only 191 in 16 years, from 1960

to 1976). According to the U.S. Department of Justice, this figure reached its

peak in 1938 with the record figure of 190 executions, compared to 147 in 1937

and 160 in 1939.

Fig. 1) `Executions by Year

1608-2000'

3) Towards the national abolition?

Despite the continuing abolitionist movement, it was only in

1972, in the case of Furman vs. Georgia, that capital punishment was

first fundamentally questioned in the United States. This particular case had

to do with a man who had been accidentally killed. The defense put forward the

argument of the unconstitutionality of capital punishment, on the basis that it

violated the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States:

«Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor

cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.» The defense further claimed that

the existing statutes in Georgia were arbitrary, capricious and irrational, and

that race appeared to be the single motivating factor separating those selected

for capital punishment from those who were not. Their final criticism, of the

`unitary trial' procedure in which the jury returns the verdict for guilt or

innocence at the same time as the sentence, was also accepted and later

changed. On these bases, the court finally declared that the statutes of the

death penalty in the State of Georgia were unconstitutional. In making this

decision this decision, taken 3 votes against 4, it was not so much the

sentence that had been criticized, as its methods of application. Only two

justices condemned the principle of the sentence itself, whereas one voted for

censure because he did not consider it as discriminatory towards minorities.

The two other justices judged that the death penalty was excessively arbitrary.

The Furman case was, nevertheless, one of the principal cases in the

1972 Supreme Court's review, along with the Earnest Aikens,

Elmer Branch, and Lucious Jackson

cases3(*).

4) Suspension by the Supreme Court

Therefore, it was on the 29th of June 1972 that the

Supreme Court first suspended capital punishment in the United States. This

moratorium commuted de facto the sentence of 629 death row inmates to

one of life imprisonment. As a quick reaction, some retentionist states enacted

new statutes to end the arbitrariness of capital sentencing, yet retained

capital punishment in the regime of the Furman decision. Thus, during

the 1970s, thirty-four States created new death penalty statutes and six

hundred people were sentenced to death. Notwithstanding, as the Supreme Court

on the whole did not recognize these laws, there were no executions from 1972

to 1976.

The President at the time, Richard Nixon, who was a fervent

advocate of death penalty, created a federal capital punishment bill that would

restore death penalty for certain federal crimes. This bill included murder,

kidnapping, treason and hijacking of planes.

5) The restoration

Under the pressure of both the States and the government, the

United States Supreme Court restored the death penalty and its new statutes in

1976 in Gregg v. Georgia. In this case, the Court decided that the new

statutes did not violate the Eighth Amendment and that these «guided

discretion statutes» could end arbitrariness. This new law also changed

the trip procedure so that the verdict of guilt or innocence would be separated

from the sentencing. In addition, the jury would be required to consider

aggravating and mitigating circumstances (or factors) in the second phase. An

aggravating factor is any important circumstance, proved by the evidence

presented during the trial (such as prior criminal conduct), which makes the

harshest penalty appropriate in the judgment. On the contrary, a mitigating

factor is any evidence regarding the defendant's character or background as

well as the circumstances of the crime that could work to reduce a sentence. It

includes parental neglect, abuse, poverty, good conduct, provocation by the

victim. If at least one mitigating factor could be proven, such as the age of

the defendant during the crime, or a mental or emotional disorder, then death

penalty could not be imposed. In a case with no mitigating factors, but where

there existed one or more aggravating circumstances, capital punishment would

be automatic. Finally, according to this new law, the Supreme Court of Georgia

would be required to review each capital sentence given for prejudice and

arbitrariness. In the end, the Supreme Court maintained that the state of

Georgia could constitutionally the execution of Gregg, and on the

2nd of July, 1976, the de facto moratorium was removed.

6) Evolution of the application of death penalty since

1976

a) Number of executions

Since the reinstatement of death penalty in 1976, its

evolution has varied considerably from decade to decade. From 1976 to the end

of the 1980s, the number of executions slowly increased. Then, there was a

resurgence in the 1990s, reaching a peak of 98 executions in 1999. Since then,

the general trend is toward a reduction, as is evident in the following

spreadsheet.

Fig. 2) United States Executions by

Year4(*)

|

1976 - 00

|

1984 - 21

|

1992 - 31

|

2000 - 85

|

|

1977 - 01

|

1985 - 18

|

1993 - 38

|

2001 - 66

|

|

1978 - 00

|

1986 - 18

|

1994 - 31

|

2002 - 71

|

|

1979 - 02

|

1987 - 25

|

1995 - 56

|

2003 - 65

|

|

1980 - 00

|

1988 - 11

|

1996 - 45

|

2004 - 59

|

|

1981 - 01

|

1989 - 16

|

1997 - 74

|

2005 - 60

|

|

1982 - 02

|

1990 - 23

|

1998 - 68

|

2006 - 53

|

|

1983 - 05

|

1991 - 14

|

1999 - 98

|

2007* - 15

|

Total: 1071

*From January to the end of April 2007

b) Number of sentences

If the number of executions has been decreasing since the

early 2000s, because of modifications in the appeal process, the number of

prisoners on death rows has not. As can be seen in the following diagram, the

number of prisoners on death row has consistently increased since 1953. It

reached a peak in 2000 with 3601 inmates on death row in the United

States5(*). The figures for

the 1st of January 2007 show that there are around 3,350 prisoners

under sentence of death. This jump in death row inmates can be explained by the

duration of the imprisonment (due to long trials and appeal processes) and also

by the still significant number of inmates sentenced to death.

Fig. 3) Prisoners on Death Row, 1953-20056(*)

c) Evolution of the criminal process

There have been subsequent evolutions regarding the definition

of capital offences, and the methods and the limits of their application. The

two main debates concern the death penalty and its application in juvenile

offenses, as well as those cases involving the mentally disabled. In June 2002, the Supreme Court case of Atkins vs.

Virginia ruled that executing mentally handicapped persons was

unconstitutional, citing the Eighth Amendment (that which prohibits "cruel and

unusual punishments"). Since then, 16 states decided to forbid capital sentence

in such cases. More recently, in Roper v. Simmons, in March 2005, the

Supreme Court declared capital punishment unconstitutional for crimes committed

before the age of 18. Before this, of the 38 retentionist states, nineteen of

them along with the federal government had set a minimum age of 18, five of

them a minimum age of 17, and the fourteen others a minimum age of 16. Since

1976, 22 inmates have been executed in seven different states (Texas, Virginia,

Georgia, Louisiana, Missouri, Oklahoma, and South Carolina) for crimes they

committed as juveniles.

Such advances suggest a trend towards national abolition.

However, for the time being and due to history, there remains the federal

judicial system of the United States, and in the people's mindset, a deep and

unchanging disposition favorable to the death sentence.

B. Criminal Law in the United States

In order to fully understand the limits of criminal law in the

United States (also known as penal law), it is necessary to briefly outline the

process. We will focus our study on general criminal law, which is applied at

the Federal level and at the State level.

1) Who sentences to death?

Certain State courts, the Federal Government, and the U.S.

Military all sanction death penalty. At the Federal level, the Supreme Court

(composed of nine justices) presides over criminal cases. It is also

responsible for judiciary, administrative and constitutional domains, and only

concerns itself with only 2% of the criminal domain. In relation to the Federal

Government, the death penalty is reserved as a solution for a large range of

offenses related to homicide, but also for treason, espionage, and trafficking

in large quantities of drugs. The Military Court can only pronounce the capital

punishment in fourteen rare cases of murder and, in times of war, for

desertion. The majority of the cases of death penalty come from State courts.

The Constitution of the United States specifies the connections between the

Federal and State institutions. In addition, every State has its own

Constitution and its own Supreme Court that is empowered to interpret it.

Therefore, each State has its own judiciary system and criminal law, resulting

in autonomy but also a great complexity of analysis. Later, this paper will

touch upon the various offenses subject to death penalty, according to each

State.

2) The United States judicial system

American law is determined by common law, which is

based on jurisprudence, that is to say the decisions given by the different

courts. During a trial, the court refers to previous cases in order to make

their decisions. This contrasts with the codified system, characteristic of

Roman Germanic law, which is organized by codes. A principal theoretical tenet

of the American system is that the defendant is innocent until proven guilty.

Also, juries are only supposed to convict if guilt is established «beyond

a reasonable doubt». There are a multitude of cases, however, where that

standard does not seem to apply. Nevertheless, the United States ratified

several international charters concerning fundamental judicial rights, such as

the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), the International Pact about

Civil and Political Rights (1996), the International Convention on the

Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (1963). Thus the American

criminal law is supposed to provide the `right to a fair trial' as a

fundamental principle. It consists of ten fundamental rights including the

right to equal treatment before the trial, the right to be judged by an

independent and impartial court, the presumption of innocence, the right to

choose a lawyer or to have a lawyer appointed by the court, the right to be

judged quickly. The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the

Constitution also guarantees all individuals equality before the law.

3) The criminal law

In the United States, the Criminal Law defines the crime and

determines the legal punishment for criminal offenses. It is based on four

primary tenets: punishment, deterrence, incapacitation, and rehabilitation. It

is assumed that by imposing punishments for crimes, society can achieve justice

and a peaceable social order. Contrary to the French penal system, the defense

is held to provide evidence in order to prove the innocence of the accused. In

other words, the defense has the burden of proof: e.g. DNA tests, and the

testimony of the witnesses. This system, as we will see in part III of the

essay, can have drawbacks for deprived people who are not able to afford a good

lawyer and are, thus, often poorly or unfairly represented. The prosecutor, who

represents the general interest--that is to say, the state--is provided ample

financial means for all that is necessary throughout the process of the trial.

Indeed, given that Common Law is based on jurisprudence, having greater

resources to search for previous cases is an important advantage during any

given trial.

The United States system is based on the adversarial system,

as opposed to the inquisitorial one. This system of law relies on the skills of

opposing lawyers, where the judge is relegated to facilitating the debate

during the trial and remains neutral.

a) At the state level

In the American criminal law system, at the state level, there

are four different courts of Law. The lowest one is the Magistrate's Court.

They are numerous, are each run by one magistrate, and are competent to give a

verdict on petty offenses (for which one risks a 6 month stint in prison or a

fine of $500 maximum) and misdemeanors (offenses incurring up to one year of

prison or less than $1000). Above the Magistrate's Court, the Trial Court is

responsible for felonies (the lowest class of crimes) and any appeals coming

from the Magistrate's Court (where the facts and the law are re-examined).

After, the Intermediate Appeals Court is responsible for any appeals from the

Trial Courts (where the law only is examined). Finally, the highest authorities

are the Supreme Courts, which are the final courts of appeal. It is substituted

by the Intermediate Appeal Courts if a state does not have a Supreme Court.

Every State maintains its own court structure and in this way

determines different offenses and punishments. In the following diagram,

composed by the Criminal Law, Lawyer Source, a general outline of the criminal

court system on the State level is presented. (Sometimes, a criminal case can

also go directly to the Federal Supreme Court.)

Fig. 4) State Criminal Court System7(*)

|

COURTS OF LIMITED JURISDICTION

These are State courts which

are responsible for hearing specific types of cases. Many criminal cases can

begin at this level. Examples of these courts include: traffic court, juvenile

court, family court, court of claims, municipal court, district court, tax

court, and county court.

|

|

COURTS OF ORIGINAL JURISDICTION

These courts have original

jurisdiction over many criminal and civil cases. These are often called Circuit

Courts or Superior Courts

|

|

CIVIL AND CRIMINAL COURTS OF APPEALS

In these courts, the

judges will review questions of law to determine whether or not the defendant

received a fair trial. Usually the appeals court will uphold the decisions made

in the original court. However, if an error occurred in the original trial or

during sentencing, the appeals court may reverse or remand the case.

|

|

STATE SUPREME COURT

The State supreme court is the highest

court on the State level. It is also called the court of last resort. The State

supreme court often hears the appeals of legal issues.

|

The United States Federal Supreme Court decides only a

fraction of the cases presented, which usually involve important questions

about the Constitution or Federal law.

b) The jury

Concerning juries, it is necessary to dissociate the Grand

Jury from the Little Jury. The Grand Jury is dedicated to judiciary accusation

and investigation. In the Federal Grand Jury and in the State one, members are

selected in the same way. First they are chosen by drawing lots, and then are

elected accordingly. Some are excluded or exempted for reasons of social or

physical handicap, or in case of particular professions on the basis of a

precise, exacting questionnaire to fill out. Before the trial, both parties can

decline an unlimited number of members, by providing good reasons, but also a

limited number without specifying why. This process of selection will be

addressed later.

The selection method of the Little Jury is the same but it

does not have the same role or action. At the State level, the case includes

either a Little Jury if the penalty is more than six months imprisonment or a

$500 fine. A ¾ majority is required for the sentence, except in cases of

capital punishment, where the decision must be unanimous. At the Federal level,

the right to ask for both the Grand and the Little Jury is cited in the Fifth

Amendment.

4) How is death penalty sentenced?

The paper will now focus on the process of the death sentence

itself (in chronological order), beginning after the prosecution. The

administration of the death penalty is divided into four steps: Sentencing,

Direct Review, State Collateral Review and Federal Habeas Corpus. A fifth stage

in the process has recently grown in importance: the Section 1983 Challenge.

During the sentencing phase, if the defendant is convicted for a capital crime

(which varies according to the jurisdiction), he must be found eligible for the

death penalty according to any aggravating or mitigating factors. The

sentencing authority then chooses between death penalty and life imprisonment.

The second step, the direct review, is a legal appeal during which the appeals

court decides whether the decision was legally taken. The decision can be

affirmed (as happens in 60% of the cases), reversed, or the defendant can be

acquitted. In the event of an affirmation on direct view, the decision is

final, but if a prisoner receives their death sentence in a State-level trial a

possible third stage remains: they can request implementation of a State

Collateral Review. Most of the time, at this point, the defendant claims

ineffective assistance of counsel, after which the court must reconsider any

evidence. However, only a mere 6% of death sentences are ever overturned after

State Collateral Review. Following this review, or for a federal death

penalty, cases go directly to stage four: Federal Habeas Corpus. This step

guarantees that State courts, through the previous two stages, have done their

best to protect the prisoner's Federal Constitutional Rights. This is an

important step as about 21% of cases are reversed through Federal Habeas

Corpus. A recent important evolution has

added a fifth and final round of appeal. Under the Civil Rights Act of

1871 -- codified in

42

U.S.C. § 1983 -- anyone is allowed to establish a

lawsuit for the purpose of protecting his civil rights. Thus, a State prisoner

can refer to the Section 1983 Challenge to question and dispute their judgment

of death. Recently, in the Hill v. McDonough case, the United States

Supreme Court approved the use of Section 1983 defense, deeming Florida's

method of execution as `cruel and unusual punishment', which is clearly

forbidden by the Eighth Amendment.

After a sentence has been finally proclaimed, the last chance

is a pardon and clemency. For federal crimes pardons can only be granted by the

President, as written in the Constitution. However, the governors of most

states have the power to grant pardons or reprieves for offenses under state

criminal law.

Finally, concerning death penalty itself, the American

criminal system is based on the justice model, which means the court punishes

the convict, `hurting him in his body and in his soul'8(*). This study will limit itself to

homicide-related offenses that are linked directly to the subject. In the

nineteenth century, states could impose death penalty for a multitude of

crimes. They gradually reduced the offenses, so that since 1977 the only crime

for which prisoners could be executed has been criminal homicide, although most

jurisdictions do require additional aggravating circumstances. The differences

existing between the jurisdictions will be discussed in part II) of the essay.

Most of the jurisdictions provide «life without

parole» as an alternative sentence to death penalty; that is to say a life

long sentence without possibility of release. On the contrary to the French

equivalent--in which a prisoner may be released on the grounds of good

behavior--in the United States, a prisoner sentenced to life imprisonment

actually spends the rest of his life in jail, unless otherwise pardoned, or if

a successful escape is carried out.

5) Time spent on death row and living conditions in

prison

Fig. 5) Average Time from Sentence to Execution (in

years)9(*)

There are at the moment more than two million people in United

States prisons. With about 300 million inhabitants in the country, this rounds

to about one person out of 150, 500 prisoners out of 100,000, compared to 98 in

France.10(*)

With the general improvements of living conditions in prison,

the international progressive movements for the defense of Human Rights and new

abolitionist countries around the world have introduced new topics of debate

about the conditions of imprisonment. One of these new topics is found in the

United States, where death row inmates usually spend between 11 and 12 years

between sentencing and the actual execution11(*). This duration has been increasing lately. As the

graph Fig. 5 shows, the average time spent in death row was around 4 years

until 1983, peaking at 12 years in 1999 and 2001. According to the article

«Vigilantism, Current Racial Threat and Death Sentences»,

published in the American Sociological Review, the time spent on death row also

varies from state to state: «Since 1972, mean state delays from first

death sentence to execution ranged from about 4.5 years (Nevada) to about 16

years (California, Nebraska).»12(*) Some inmates have been on death row for more than 20

years. During this time, they are totally isolated from the rest of the

prisoners, they are excluded from general prison activities, and they spend 23

hours per day in their cells. This situation is considered in itself as a

«social death penalty» by the French Catholic association

«Collectif Octobre 2001»13(*). This unnecessarily long duration is due to the

process of appeal. During the eighteenth century, the time spent in death row

could be measured in days or weeks. But, during the suspension of the death

penalty from 1972 to 1976, numerous reforms were introduced to create a less

arbitrary system. This has resulted in lengthier appeals, as mandatory

sentencing reviews have become the norm, and continual changes in laws and

technology have necessitated reexamination of individual sentences. Justice

Stephen Breyer noted that the «astonishingly long delays» experienced

by the inmates were largely a result not of frivolous appeals on their part,

but rather of "constitutionally defective death penalty

procedures.»14(*)

Such delays have been criticized by the opponents of death penalty, who

consider that all the methods of execution violate the Eighth Amendment of the

Constitution, which forbids «cruel and unusual punishment». The

unbearable and uncertain waiting on death row is also unconstitutional in

itself for the same reason. To execute an inmate after they have spent several

years in prison makes the notions of deterrence and fair punishment, the two

main social goals of the death penalty, lose their meaning. In Jamaica, if a

convicted person has been on death row for more than five years, his sentence

is automatically commuted to life imprisonment. The Jamaican court system

considers the death penalty to be a failed system as no inmate deserves to

endure such a long period of waiting, which effectively doubles the punishment,

and is seen as «inhumane and degrading». Similarly, in Uganda the

maximum duration is three years.

This solitary confinement is effectively a second punishment,

especially since they never know precisely when they will be executed. For some

of them, this isolation and uncertainty result in a deterioration of their

mental state. Psychologists and lawyers talk about the «death row

phenomenon» to describe the living conditions in death row (isolation,

uncertainty and duration) and the «death row syndrome» to talk about

the psychological effects that result from it. The waiting, loneliness and

uncertainty are a form of torture that often makes inmates suicidal, delusional

and insane. In addition, since 2002 it is unconstitutional to execute a

mentally handicapped person. If a death row inmate is considered as one, the

Court has to reexamine his case.

C. Geographic analysis of abolitionist and

retentionist States today

1) Retentionist jurisdictions

Federally, thirty-eight States still have death penalty.

Geographically, this number includes the southern states15(*) of: Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas,

Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North

Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, plus California,

Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Utah, Colorado,

Montana, Wyoming, (for the western region), South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas,

Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, (for the Midwest) and Pennsylvania,

Connecticut, New York, New Hampshire, and New Jersey for the Northeast. The

states of New York, South Dakota, New Hampshire, and New Jersey and Kansas for

the majority situated in the Northeast have not had any executions since 1976.

In 2004, the death penalty statute in the states of Kansas and New York was

declared unconstitutional, although there is one man is still waiting on death

row in the State of New York.

By using the division made by the US Census Bureau, we can

notice that the four different regions (West, Midwest, Northeast and South) can

be themselves characterized as retentionist or abolitionist states. Indeed, all

eleven states classified in the Western region have death penalty statutes; and

fifteen states out of sixteen of those in the southern region use this sentence

as well. The Midwest and Northeast regions appear more inclined to retentionist

practices, with seven out of twelve, and five out of nine, respectively.

However, we will see further that, after having taken into account different

parameters, the South is the primary region which can be considered as

retentionist in the U.S.

a) Geographical analysis of the retentionist states

Fig. 6) Map of the Abolitionist and Retentionist

States16(*)

On this map, showing the abolitionist and retentionist states,

we can see that most of the states without the death penalty are situated in

the Midwest and Northeast. We will come back to this geographical configuration

later and try to analyze it.

On the following map, we can notice that the most progressive

states on this issue and the recent evolutions on death penalty sentencing have

been concentrated in the North. Such advances taken into account include the

death penalty statutes being declared unconstitutional in 2004 in Kansas and

New York. Former evolutions are seen in the states of South Dakota, Kansas, New

York, New Hampshire and New Jersey, where there has been no execution since the

reinstallation of capital punishment in 1976.

Fig. 7) Death Penalty Statutes in the United

States17(*)

* Excluding Federal Government

The U.S. Government and U.S. Military also have death penalty

written into their laws, but the number of prisoners sentenced to death or

executed is not very significant. The U.S. Military has not had any executions

since 1961; however 9 inmates remain waiting on military death row. The U.S.

Government has authorized 48 prosecutions since 1990 and only 3 people have

been executed under this jurisdiction. All three were executed under the

administration of President George W. Bush (1994-2000), whose term in office

has also seen federal death row more than double in size. Given that in total

the Federal Criminal Court has prosecuted only 48 people in 15 years (in

comparison with 884 at the States level), then the frequency has increased

recently, as is evident on the table below. There are currently 44 prisoners on

federal death row.

Fig. 8) Number of Federal Death Sentences

1990-200518(*)

|

Year

|

2005

|

04

|

03

|

02

|

01

|

00

|

99

|

98

|

97

|

96

|

95

|

94

|

93

|

92

|

91

|

90

|

|

Federal Death Sentences

|

6

|

10

|

2

|

5

|

2

|

2

|

1

|

5

|

3

|

4

|

2

|

0

|

5

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

b) Evolution since 1976

Between the reinstatement of death penalty in 1976 and April

1st, 2007, up to 1072 inmates have been executed--a figure that has

grown within the first four months of 2007, when 15 inmates were executed. Even

though 38 States have the capital sentence in their laws, 80% of the executions

that have happened since 1976 have taken place in the southern states. Texas

and Virginia alone account for almost half of the number of executions (with,

respectively, 392 and 98 between 1976 and 2006, making for a total of 490 of

the 1072 total), followed by Oklahoma, Missouri and Florida. Except for the

case of Missouri, these states are all situated in the South.

Within the first four months of this year (2007), there were

15 executions in the country and 13 were carried out in Texas. The two others

took place in Oklahoma and in Ohio. By comparing the figures concerning the

executions since 1976 and in the recent years, on the spreadsheet above and in

the appendix 4 «Executions by State'19(*), we can observe that the general trend has not

significantly changed. Texas has always been, since 1976, the state where the

number of executions has been the highest. The states of Virginia, Oklahoma and

Florida are just behind Texas, gathering all together more than the half of the

total (638 executions out of 1072).

Nevertheless, few states seem to change their attachment to

death penalty. The state of Missouri (which was the fourth-most prolific state

in this classification), seems to move toward a more progressive policy.

Indeed, the last execution in the state took place in October 2005 and a

moratorium on the executions was imposed in 2006 and has been renewed since.

However, the state of Ohio, on the contrary, which was the thirteenth state

concerning the number of executions since 1976, was on the second position

after Texas for the 2006 figures.

The hypothesis of the South being more retentionist is and

will be confirm further, taking into account the number of executions, the

number of death row inmates, and further in the essay, with the example of the

state of Texas, by using the judicial process.

c) A stricter application in the South?

|

Fig. 9 ) Executions By State20(*)

|

|

STATE

|

TOTAL EXECUTIONS

|

EXECUTIONS IN 2006

|

EXECUTIONS IN THE FIRST FOUR MONTH OF 2007

|

|

TEXAS

|

392

|

24

|

13

|

|

VIRGINIA

|

98

|

4

|

|

|

OKLAHOMA

|

84

|

4

|

1

|

|

MISSOURI

|

66

|

|

|

|

FLORIDA

|

64

|

4

|

|

|

NORTH CAROLINA

|

43

|

4

|

|

|

GEORGIA

|

39

|

|

|

|

SOUTH CAROLINA

|

36

|

1

|

|

|

ALABAMA

|

35

|

1

|

|

|

LOUISIANA

|

27

|

|

|

|

ARKANSAS

|

27

|

|

|

|

ARIZONA

|

22

|

|

|

|

OHIO

|

24

|

5

|

1

|

|

INDIANA

|

17

|

1

|

|

|

DELAWARE

|

14

|

|

|

|

CALIFORNIA

|

13

|

1

|

|

|

ILLINOIS

|

12

|

|

|

|

NEVADA

|

12

|

1

|

|

|

MISSISSIPPI

|

8

|

1

|

|

|

UTAH

|

6

|

|

|

|

MARYLAND

|

5

|

|

|

|

WASHINGTON

|

4

|

|

|

|

NEBRASKA

|

3

|

|

|

|

MONTANA

|

3

|

1

|

|

|

PENNSYLVANIA

|

3

|

|

|

|

U. S. FEDERAL GOVERNMENT

|

3

|

|

|

|

KENTUCKY

|

2

|

|

|

|

TENNESSEE

|

2

|

1

|

|

|

OREGON

|

2

|

|

|

|

COLORADO

|

1

|

|

|

|

CONNECTICUT

|

1

|

|

|

|

IDAHO

|

1

|

|

|

|

NEW MEXICO

|

1

|

|

|

|

WYOMING

|

1

|

|

|

|

TOTAL

|

1072

|

53

|

15

|

As we can see in this spreadsheet, established by the Death

Penalty Information Center21(*), in 2006, 53 people were executed in 14 different

States: 24 inmates were executed in Texas, 5 in Ohio, 4 in Florida, North

Carolina, Oklahoma and Virginia, and 1 in Indiana, Alabama, Mississippi, South

Carolina, Tennessee, California, Montana, and Nevada. Such figures clearly show

that the southern states use death penalty significantly more than in other

regions of the United States. Indeed, a majority of the jurisdictions (nine out

of fourteen) where executions were carried out in 2006 are situated in the

South: Texas, Florida, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Virginia, Alabama,

Mississippi, South Carolina, and Tennessee. The others, Ohio, Indiana, Nevada,

Montana and California, are exceptions and as such will not be issues of

primary focus in this essay.

Fig. 10) Executions by Region*22(*)

|

This spreadsheet shows the number of executions (at the

federal and State level) by state since 1976.

*including federal executions which are listed in the region

in which the crime was committed

|

It is obvious, according to the diagram Fig. 10, that there

are many more executions in the southern states. Indeed, 82% of the executions

between 1976 and today took place in the South.

Not only are executions in the South more frequent, but the

number of prosecutions there is much higher as well. California has the highest

number of inmates on death row with 660 out of 3357 nationwide23(*), compared to 397 in Florida,

and 393 in Texas. These figures will be analyzed and compare to the number of

inhabitants in part two to show that the southern states are more severe and

discriminatory in their prosecution. We will be able to see also that the

example of California is not very relevant and that it is necessary to use the

rate of inmates per inhabitant in order to yield legitimate and comparative

numbers.

We will also try to explain that there exist historical, as

well as economical reasons for such a strict application, and will analyze the

example of the state of Texas to find proof of this particular form of

judiciary process.

2) States with moratoria

Among the states with death penalty statutes, several have

recently imposed a moratorium on executions. A moratorium is a temporary

suspension of executions while a legislative study commission examines the

death penalty judicial system. Death penalty trials and appeals are not

suspended during the study, only executions. Recent events, such as the

controversy relating to the humaneness (or lack thereof) of the lethal

injection practice, have resulted in moratoria in various states. In most

states, a governor can impose a moratorium unilaterally. Most of the time, a

governor or a senator requests a moratorium on the grounds of the application

of the death penalty, rather than for ethical reasons. The state legislatures,

made up of a state house of representatives and state senate, can also pass

moratorium laws. Both bodies must pass the same law for it to take effect, and

the governor has the power to veto any law if he wants to. Courts cannot impose

a moratorium but can declare specific laws unconstitutional or suspend

executions pending resolution of problems that violate their respective state

or federal constitutions. If that happens, the states can appeal to a higher

court or change the laws to comply with the court's concerns.

Usually, during the moratorium, a commission is created to

study precise aspects of the death sentence in order to determine the fairness

or the constitutionality of it. Several states have currently placed moratoria

on the executions so that the procedures of execution by injection can be

reviewed. But as the debate nowadays is very sensitive, and incites more and

more states to impose a moratorium, and as the average duration of a moratorium

is three months, it is difficult to give a clear and faithful picture of the

states currently holding a moratorium. We will focus on the important moratoria

that were imposed recently and their explanations.

a) States where death penalty statutes were declared

unconstitutional

In New York, the state's High Court ruled in the case of

People vs. LaValle (June 2004) that the state's death penalty statute was

unconstitutional. The defense argued that the death sentence had been

improperly imposed on two grounds: first, one of the jurors had been unfairly

biased from the beginning of the trial, and had expressed partiality towards

assigning the death penalty to rapists and murderers; and second, the trial was

essentially based on the defendant's declarations and on an eyewitness

testimony. For these reasons the court overturned LaValle's conviction along

with his pending death sentence.

In the state of Kansas as well, death penalty was considered

unconstitutional in 2004, concerning the manner in which jurors should weigh

death penalty arguments during sentencing phases. Kansas law provides that

when juries find arguments for and against execution to be equal in weight,

their decision should favor a death sentence. However, this was decided to be

a violation of both the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments of the US

Constitution.

Thus, the states of New York and Kansas are currently the

closest states to abolish death penalty. According to Sam Millsap, a former

prosecutor who used to require death sentences but who now is an abolitionist;

a moratorium is «a very encouraging movement toward abolition».

«I believe that the death penalty will be abolished in the U.S. but it

will be a slow process and a state-by-state process.»24(*)

b) Moratoria for general death penalty concerns

Since death penalty was reinstated in Illinois in 1977, 12 men

have been executed. During that same period, 13 men were freed from death row.

The ratio of miscarriage of justice is thus more than ½. In January 2000,

this finding prompted the outgoing governor of Illinois, Republican George H.

Ryan to impose a moratorium on every execution on a technical foundation:

We have now freed more people than we have put to death

under our system - 13 people have been exonerated and 12 have been put to

death. There is a flaw in the system, without question, and it needs to be

studied... I will not approve any more executions in this state until I have

the opportunity to review the recommendations of the commission that I will

establish.

Just before leaving the office in January of 2003, he

commuted 167 inmates' capital sentences to life imprisonment and pardoned 4

inmates. When Democrat Rod Blagojevich was elected governor in 2002, one of his

first acts was an attempt to revoke some of Ryan's commutations but the

moratorium remained.

In New Jersey, in December 2005, a report was released by a

commission into the fairness and financial costs of the death penalty and

alternatives to capital punishment. From its conclusions, in January of 2006,

Governor Richard J. Codey placed a one-year moratorium on the executions in the

state, where no inmate has been executed since 1963. This was the first time

that a moratorium was instituted by the legislation, rather than by executive

order, in the United States.

In the State of Maryland, Governor Parris N. Glendening placed

a moratorium by executive order, on the 9th of May, 2002, to

determine if racial prejudices could influence the sentencing of the death

penalty. But the subsequent governor, Robert Ehrlich, resumed the executions in

2004.

c) Moratoria because of lethal injection issue

In Ohio, on the 3rd of May 2006, the execution of Joseph Clark

reinforced the already existing debate on lethal injection. His execution

lasted one and a half hour. At the beginning of the execution, Joseph Clark,

condemned for several armed attacks, was screaming "It does not work!» His

vein exploded and media witnesses reported that they heard "moaning, crying out

and guttural noises» before he finally died.

Two years after Governor Ehrlich reenacted death penalty in

Maryland in 2004, the State High Court ruled that executions would be suspended

until the process of lethal injections is reviewed.

The case of Angel Nieves Diaz, executed on 13th December 2006,

in Florida, renewed the debate on lethal injection. Indeed, the first of the

three injections, dedicated to stop the prisoner from breathing, was not strong

enough to cause the awaited effect. The execution lasted 34 minutes, whereas it

is supposed to last from 10 to 15 minutes. Following this botched execution,

Governor Jeb Bush suspended all executions on December 15, 2006, until a

commission investigates and gives its report on the lethal injection

procedure.

In January 2006, in a Letter to the California Assembly, a

Commission ruled that the lethal injection was unconstitutional and imposed a

moratorium:

Given that DNA testing and other new evidence has proven

that more than 121 people who sat on death rows around the country were

actually innocent of the crimes for which they were convicted, we agree that a

temporary suspension of executions in California is necessary while we ensure,

as much as possible, that the administration of criminal justice in this state

is just, fair, and accurate.

U.S. District Judge Jeremy Fogel imposed a moratorium on the

death penalty in the state of California on December 15, 2006, ruling that the

implementation used in California was unconstitutional. State proposals are due

in June 2007.

In Missouri, U.S. District Judge Fernando J. Gaitan, Jr. of

the United States District Court for the Western District of Missouri in Kansas

City suspended the state's death penalty on June 26, 2006. The state's lethal

injection protocol was considered to be against the Eighth Amendment because

the procedures for implementing lethal injections were too vague, and the state

had no qualified anesthesiologist to perform lethal injections.

In North Carolina, there is a de facto moratorium in

place following a decision by the state's medical board that physicians cannot

participate in executions, which is a requirement under State and Federal law.

Very recently, on the 2nd of February 2007, Phil

Bredesen, governor of Tennessee, placed a three-month moratorium on the

executions in order to reconsider the methods of execution used in the state

(lethal injection and electrocution.)

As can be seen, a moratorium is often imposed in the face of

doubts concerning the methods of execution, or the fairness of a death

sentence. During this suspension, an impartial commission is often asked to

study the controversial aspect. However, some abolitionists contend that a

moratorium is not enough. The states of Illinois and New Jersey seem to be

moving towards abolishing the death penalty due to the resolute convictions of

protest groups.

Despite the questions raised in progressive evolutions, the

United States are far from universal abolition. Indeed, some states are

regressing in this area: Montana, Connecticut, Mississippi and Tennessee

resumed executions after a long period of de facto moratorium.

3) Abolitionist states

In total, thirteen jurisdictions have completely abolished

death penalty from their law25(*): Alaska, Hawaii, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, North

Dakota, Wisconsin, West Virginia, Rhode Island, Vermont, Massachusetts, Maine,

and the District of Columbia. All these abolitionist states are situated in the

North, firmly suggesting that this region is more progressive. This position

can be explained by different factors: historical, economic, social or

demographic. We will try to study this particular geographical division

utilizing the characteristics of the South and the judiciary process in Texas

as references.

II Geographical analysis of the application of death

penalty

D. A different application in the

law

Among the retentionist States, the criminal systems differ

according to the type of offense, and the method and application of death

penalty. To take this study further would require comparing the criminal law

systems of to each jurisdiction in their entirety, however this paper will

focus its analysis on the capital crimes and the various execution methods

used, putting aside the different processes used during the trial and appeal

phase.

1) Offenses subject to the death penalty

At the federal level, capital punishment can result from 42

offenses, including 38 related to homicide. However, some states have stricter

laws that apply in other cases. As shown in the appendix on page 8126(*), crimes subject to the death

penalty vary by jurisdiction. All the jurisdictions which use capital

punishment (38 retentionist states, the U.S. Government and U.S. Military)

designate the highest grade of murder as a capital crime. In addition, there

are a growing number of states that allow the execution of convicted child

molesters. In Oklahoma, a bill was enacted that permits the death penalty for

anyone convicted of rape, forced sodomy, lewd molestation or rape of a child

under 14 years of age. In addition, most jurisdictions require additional

aggravating factors for homicide-related cases. Treason is also a capital

offense in several jurisdictions. In California, for example, the death penalty

also can be imposed for wrecking a train, high treason and committing perjury

that results in death. Other capital crimes include: aggravated kidnapping in

Georgia, Idaho, Kentucky and South Carolina; train wrecking which leads to a

person's death, and perjury which leads to a person's death in California;

aircraft hijacking in Georgia and Mississippi; aggravated

rape of a victim the under age

of 12 in Louisiana; capital sexual battery in Florida; and capital narcotics

conspiracy in Florida and New Jersey.

At the federal level, death penalty crimes include various

degrees and types of murder as well as treason,

espionage, large scale

drug trafficking, kidnapping across State lines resulting in the victim's

death, and attempting to kill any officer, juror, or witness in cases involving

a continuing criminal enterprise.

Under U.S. Military law; there are 14 crimes subject to the

death penalty. Some of them, such as desertion, are only applicable in times of

war.

Despite the variety of capital crimes among the various

criminal systems, no one has been executed for a crime which was not a homicide

since the reinstatement of the death penalty in 1976. The last execution for a

rape was in 1964.

1) The different methods of execution used

Five methods of execution are prescribed in the United States:

the lethal injection (in most cases27(*)), the electric chair, the gas chamber (or lethal

gas), hanging, and the firing squad.

a) Description

- Lethal injection

The procedure of lethal injection is the most common, and

varies from state to state. However, in most jurisdictions, a combination of

three drugs is used. The first is a barbiturate that makes the prisoner

unconscious. The second one is a muscle relaxant that paralyzes the diaphragm

and lungs. Finally, the third causes cardiac arrest. Each chemical is fatal in

the amounts administered and the procedure is supposed to last between three

and seven minutes after the first injection. Nevertheless, sometimes it can

happen that a vein collapses or the injection cannot be properly inserted. Some

states give an extra sedative injection to facilitate the insertion.

Lethal injection is considered as the most `humane' method, in

comparison with the other methods, but it has been more and more criticized due

to problems with the executions. For example, on May 3rd 2006,

Joseph Clark was executed in Ohio in such inadequate conditions that the

prison's authorities decided to close the curtain so that the witnesses would

not see the results. The execution lasted one and a half hours instead of a few

minutes. Just before this event, The Lancet, a British medical review,

had published an article about the process used, claiming that «there was

no assessment of the depth of anesthesia before the paralyzing agent and

potassium chloride were injected.»28(*) According to the journal, in most cases the convicted

dies «awake, paralyzed, unable to move, to breathe, while potassium burned

through your veins». The article denounces the conditions with which

prisoners convicted to death are executed as insufficient even for

veterinarians to kill an animal.

«Data from autopsies following 49 executions in Arizona,

Georgia and North and South Carolina, showed that concentrations of the drug in

the blood in 43 cases were lower than that needed for surgery. Twenty-one

prisoners had drug levels that were consistent with awareness.»29(*)

Another example the same year, on the 13th of

December, 2006, with the execution of Angel Diaz in Florida, renewed the debate

on the lethal injection method. It required 34 minutes and a second dose of

chemicals. The extensive debates concerning this method of execution have

contributed to a moratorium being declared in one pro-capital punishment

state.

- Electric chair

The electric chair is the second most used method of

execution. The procedure is generally divided into three different

electrocutions. The first one lasts eight seconds, programmed at 2,300 volts,

followed by 1,000 volts for 22 seconds, then 2,300 volts for eight seconds. If

the offender is not pronounced dead, the execution cycle is then repeated from

the beginning.

The most common problems encountered are burning parts of the

body, and a failure to cause death despite repeated shocks. If it is seen as

violent, the electric chair is still the second most commonly used method right

up till 2006, in Virginia. In October 2001, the Supreme Court of Georgia

claimed that the electric chair was a cruel and unusual punishment and forbade

the method in the state.

- Lethal gas

For the lethal gas method, the inmate is strapped down on

different parts of his body (chest, waist, arms, and ankles), and wears a mask.

The room is equipped with metal containers where a sulphuric acid solution and

cyanide pellets are placed. If the prisoners take a deep breath, they are

unconscious within a few seconds. However, if they hold their breath, it can

take much longer, and the prisoner usually goes into convulsions. Death usually

occurs within 6 to 18 minutes of the lethal gas emissions caused by hypoxia,

the cutting-off of oxygen to the brain.

For this method, the most common problems are the obvious

agony suffered by the inmates and the length of time before they actually die.

A federal court in California found this method to be a cruel and unusual

punishment.

- Hanging

For execution by hanging, the "drop" must be tailored to the

prisoner's weight, to deliver the precise force to the neck (1260 lbf²

[pounds per square foot]) to ensure a quick death. The rope is then placed

around the convict's neck. If properly done, the inmate dies by dislocation of

the third and fourth cervical vertebrae, or by asphyxiation. If the rope is too

long, the inmate could be decapitated, and if it is too short, the

strangulation could take as long as 45 minutes. However, instantaneous death

rarely occurs with this method.

- Firing squad

The last method, firing squad, which is the least used, is

also the least precise and can last very long. The offender is bound to a chair

and has a white cloth circle attached by Velcro to the area over the offender's

heart. The chair is surrounded by sandbags to absorb the inmate's blood. The

squad, made up of three to six shooters, fires simultaneously. One of them has

blank rounds in his weapon but no one knows which member has them. The shooters

aim at the chest, because it is easier to hit than the head, causing rupture of

the heart, large blood vessels, and lungs, so that the inmate dies of

hemorrhage and shock. Sometimes, the officer in charge gives the prisoner a

pistol shot into the head to finish them off after the initial volley has

failed to kill them.

b) The application of each method

The majority of retentionist states utilize the lethal

injection method. Among the 38 States with death penalty statutes, 19 States

and the federal government only authorize lethal injection as the sole method

of execution and 18 others offer this method as an alternative method of

execution, to be used depending on the inmate's choice, the sentence, or the

unconstitutionality of the main method. Electrocution is the sole option in 10

States (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Illinois, Kentucky, Nebraska, Oklahoma,

South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia). In the remaining 8 States, the gas

chamber, hanging, or a firing squad are the alternatives to lethal injection.

Execution by lethal gas is an alternative method in four States: Arizona,

California, Missouri and Wyoming; while in New Hampshire and Washington hanging

is an alternative. Finally, death by firing squad is an alternative method in

Idaho and Oklahoma. Nebraska is the only State where electrocution is the sole

method of execution.

Fig. 11) Methods of Executions and their Frequency

Since 197630(*)

|

Lethal Injection

|

903

|

|

Electric Chair

|

153

|

|

Gas Chamber

|

11

|

|

Hanging

|

3

|

|

Firing Squad

|

2

|

Since 1976, lethal injection has been the method most commonly

used, as displayed in the table above. Of the 1072 inmates executed since 1976,

903 were killed by lethal injection, representing more than 84% of the total.

The electric chair has been the second most used method since 1976 (14% of the

total), the last electrocution being in Virginia, in 2006. The gas chamber was

last used in Arizona in 1999. Hanging and firing squad were carried out for the

last time in 1996, in Delaware and Utah, respectively. Even if lethal injection

has been questioned lately, it remains the least `inhumane' or at least the

quickest and a priori less painful method, which explains why only a

few prisoners have ever requested one of the alternative methods. Between the

beginning of this year and the end of April 2007, all 15 executions carried out

were done by lethal injection.

E. Regional analysis and first

explanations

As we saw earlier, there have been many more executions and

death row inmates in the south of the United States than in the north. As

previously outlined, 392 of the 1072 executions were carried out in the single

state of Texas, representing 36.5% of the total. Together, the states of the

South gather 879, i.e. almost 82% of the total executions. The regions of the

Northeast and West have the lowest number of executions, with only 69 since

1976, being 6.4% of the 1072 total. Such observations on geographical

disparities date back from the beginning of the history of death penalty. How

can such differences by region be explained? Many studies have been carried on

to discover the reason. Before proposing the explanation of racial

discrimination and the unbalanced criminal law (with the case study of Texas),

let's have a look at the other ones that have been analyzed.

1) Is there a link between the Republican Party and the death

penalty?

It is also important to recall that, even if we have a picture

of the Republican Party as a very right-winger one, it «was born from a

spontaneous revolution against slavery, [but] it proclaimed itself in favor of

«law and order», that is to say in favor of a rigorous policy on the

racial issue.»31(*)

According to J.P Lassale, The Republican Party is influenced by «the

«new right wing», and the religious fundamentalism which supports it.

(...) Today, the Republican values correspond to the strongly conservative

tendencies of American public opinion.»32(*)

Some studies have tried to establish a link between the

political parties and the presence or absence of the death penalty as well as

its application. Such investigations have been carried out to determine

precisely why or why not the death penalty is employed. According to the

conservatives, deterrence is the best antidote for crime:

The threat of the death chamber will save many innocent

victims from criminal violence. But liberals believe that crime is caused by

inequitable conditions (...), so they are skeptical about harsh sanctions.

(...) We expect more death sentences where conservative values

dominate.33(*)

Thus, a parallel can be done between the Republican Party, the

most conservative one, and a strict application of the death penalty. Let's now

try to analyze the facts.

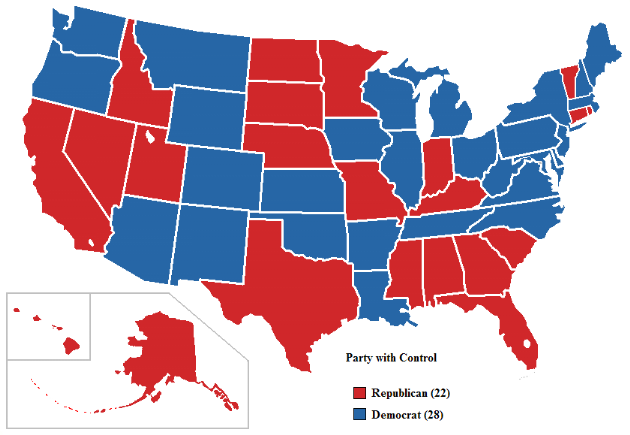

Fig. 12) Party control, Governors as of January

200734(*)

At the beginning of the year 2007, 22 states were ruled by

Republican governors and 28 by Democrat ones. Since 1975, the District of

Columbia has been ruled by a popularly elected mayor and city council, but

there is no governor. Adrian Fenty, the current mayor, is a Democrat. In 6 of

the 13 jurisdictions which have no death penalty statutes, the party in office

is Democrat (Iowa, Maine, Michigan, West Virginia, Wisconsin and the District

of Colombia), and in the seven others, the Republican Party is governing.

Within the 38 retentionist states, 16 are Republican and 22 are Democrat. Thus,

we cannot conclude that there is a link between the Republican Party and the

application of the death penalty.

Nevertheless, one can observe that among the states with the

highest number of executions (see figure 9 on page 20) the majority of them are

ruled by the Republican Party. Indeed, among the nine states most likely to

execute (Texas, Virginia, Oklahoma, Missouri, Florida, North Carolina, Georgia,

South Carolina, and Alabama), six are governed by a Republican political

majority (Texas, Missouri, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, Alabama).

There may be a link between the Republican Party and death

penalty, considering where it is applied, but apparently, not concerning its

presence or absence in the law. It would be interesting to continue this

analysis of death penalty's conspicuity in the law, but we will stop it there

in order to pursue another hypothesis.

2) The historical explanation for a stricter application in

the South

Various studies also have been carried out to show the link

between the more widespread application of the capital sentence in the southern

states and the fact that they were pro-slavery before the American

Revolution.

In the article `Vigilantism, Current Racial Treat, and Death

Sentences', from The American Sociological Review, a group of scholars

attempted to highlight the link between the slavery past of the southern States

and the fact that they use the death penalty more strictly and more often.

«The states that once had the highest lynching rates now appear to use the

death sentence most often. (...) Death sentences [are] especially likely in

states with the largest minority populations that also had a history of

frequent vigilante violence.»35(*) They also explain the stricter application of death

sentences in the south by what they call the `racial threat'. «Larger

black populations produce increased votes for anti-minority candidates (...),

who often support harsh punishments.»

In From Lynch Mobs to the Killing State, a collection

of essays edited in 2006, Timothy Kaufman-Osborn makes an insightful and

well-developed examination of the contention that pervasive racism in the

criminal justice system renders the contemporary execution of African-American

men as unjust as the historical lynchings that occurred throughout the United

States. Ultimately, he uses the term «lynching» to describe the

contemporary capital punishment, which «conceals as much as it

reveals.» It is clear that some authors believe racism is a root cause of

discrimination in the capital justice system.

Thus, racial discrimination seems to be at the origin of such

differences of application of death penalty. In order to justify such a

hypothesis, we will try to compare death penalty numbers to other figures,

related to social, economic and racial parameters.

F. Comparison with other figures

As we have seen, the figures show that the southern states use

the death penalty more often than the northern ones36(*). But it is necessary to use

demographic, racial and economic parameters to prove any discrimination. This

section will compare the death row population and the number of executions to

the number of inhabitants by state before putting forward a hypothesis that the

southern states use death penalty more readily or more discriminatorily. It

will also analyze the composition of the prison population by race and compare

the figures of the death row inmates to the inequality of income to provide

evidence of a racial, social and economic discrimination. Finally, we will

present the crime rates by region.

1) Demographic analysis

a) Proportion of death row inmates related to state

population

According to the following spreadsheet, the overall number of

death row inmates in the population of each State varies considerably, with

disparities reaching 400%. This ratio between the death row population and the

total population of each state is a better source of information with which to

compare the number of death row inmates. Indeed, it permits to rationalize the

number of inmates in California, which is the highest nationwide with 660

prisoners in death row, in comparison with the national average of 86.95. Due

to the large population in California, when measured in terms of inmate

proportionality, the state of California holds the 11th position.

Conversely, the state of Alabama, which is less populous but counts only 195

death row inmates, occupies the first position of inmates per person. The State

rate, 4.24 inmates per 100,000, is almost 4 times superior to the average of

1.14.

Fig. 13) Number of Inmates per 10.000 Inhabitants in

200637(*)

|

State

|

2006 Population (x 10,000)

|

# of death row inmates

|

Rate per 10.000 pop.

|

|

Alabama

|

459,9

|

195

|

0,424

|

|

Nevada

|

249,6

|

80

|

0,321

|

|

Oklahoma

|

357,9

|

88

|

0,246

|

|

Mississippi

|

291,1

|

66

|

0,227

|

|

Florida

|

1809

|

397

|

0,219

|

|

Delaware

|

85,3

|

18

|

0,211

|

|

North Carolina

|

885,7

|

185

|

0,209

|

|

Louisiana

|

428,8

|

88

|

0,205

|

|

Arizona

|

616,6

|

124

|

0,201

|

|

Pennsylvania

|

1244,1

|

226

|

0,182